Bloomberg News | January 14, 2025 |

Credit: EPA

A few miles south of the Grand Canyon, thousands of tons of uranium ore, reddish-gray, blue and radioactive, are piled up high in a clearing in the forest.

They’ve been there for months, stranded by a standoff between the mining company that dug them deep out of the ground, Energy Fuels Inc., and the leader of the Navajo Nation, Buu Nygren.

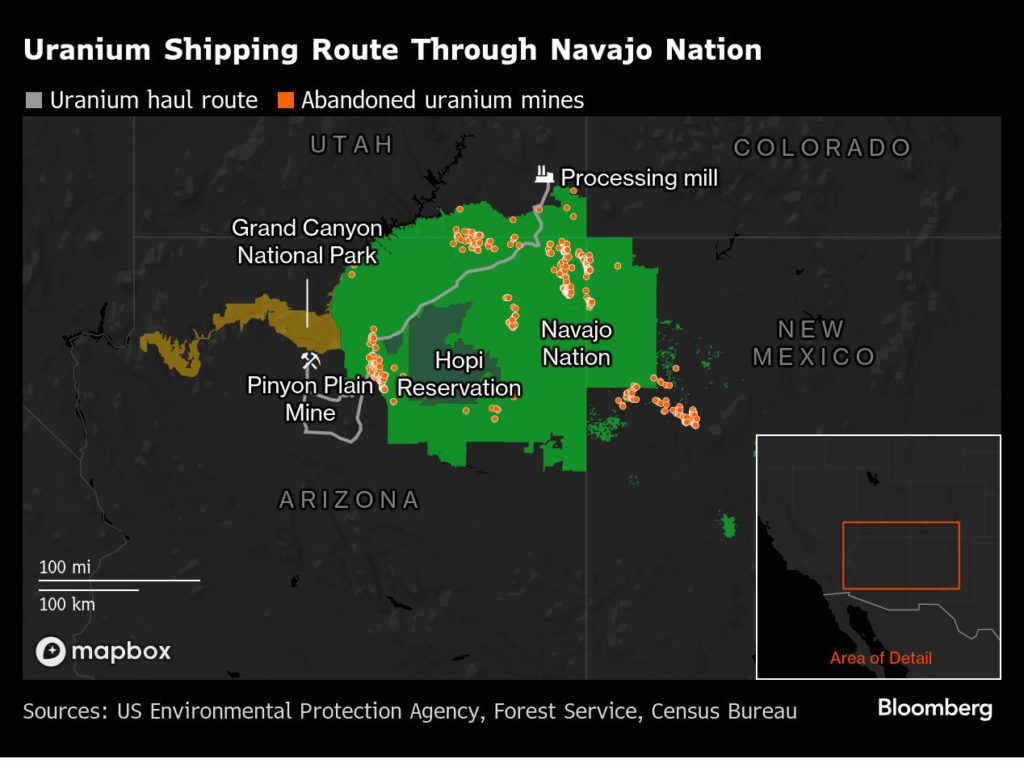

Back in the summer, Energy Fuels had triggered an uproar when it loaded some of the ore onto a truck, slapped a “radioactive” sign over the taillights and drove it through the heart of Navajo territory.

Radioactive is an alarming word anywhere, but here in Navajo country, surrounded by hundreds of abandoned uranium mines that powered America’s nuclear arms race with the USSR and spewed toxic waste into the land, it causes terror. Those fears have only grown the past couple years as nuclear power came back in vogue and sparked a uranium rush in mining camps all across the Southwest.

So when the news made it to Nygren that morning, he was furious. No one had sought his consent for the shipment. He quickly ordered dozens of police officers to throw on their sirens, fan out and intercept the truck.

The dragnet turned up nothing in the end — the truck snuck through — but the hard-line response delivered a warning, amplified over social media and ratified days later by the governor of Arizona, to the miners: Stay out of Navajo country.

Cut off from the lone processing mill in the US — all the main routes cut through Navajo territory — executives at Energy Fuels stockpiled it by the entrance of the mine. When the heaps of crushed rock grew too sprawling, they pulled the miners out of the tunnels and turned the drilling machines off.

The standoff represents the ugly side of the world’s sudden re-embrace of nuclear power. Yes, there’s the promise of a steady stream of clean energy to fuel the AI boom, fight climate change and, in the wake of Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, replace Russian oil and gas. But there’s also the fear — both around the nuclear reactor sites popping up across the world and in the communities surrounding mining operations in Australia, Kyrgyzstan and Navajo Nation, where the locals are still documenting cancer cases decades after the last of the Cold War-era outfits shut down.

It’s like the backlash erupting over all sorts of other mining projects crucial to the transition away from fossil fuels — lithium, nickel, copper, cobalt, zinc — just with the added threat of radioactivity.

“Generations and generations of my people have been hurt,” Nygren, 38, said in an interview. “Go find uranium somewhere else.”

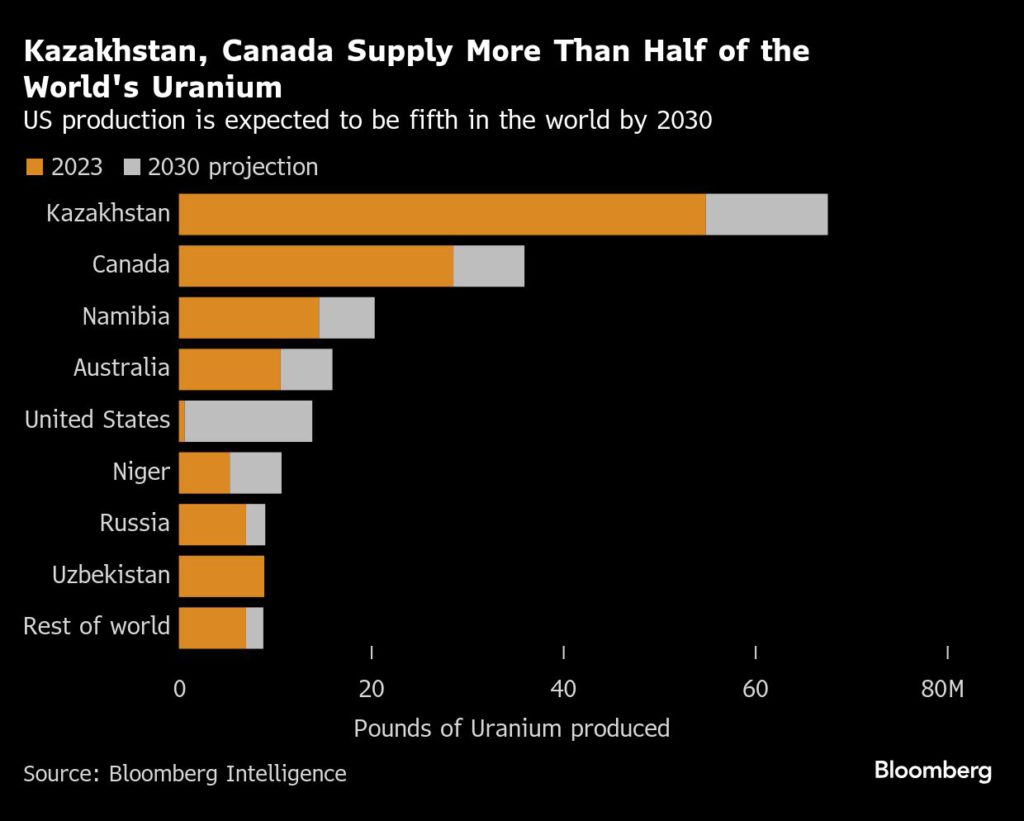

Truth is there isn’t all that much uranium at the Energy Fuels mine, known as Pinyon Plain, or any of the other half-dozen mines that opened in the Southwest the past couple years.

In most cases, crews are simply combing through the untouched veins of mines that were closed when the 2011 Fukushima disaster scared global leaders away from nuclear power and crashed the uranium market. Pooled all together, they only hold a fraction of the hundreds of millions of pounds of ore buried in any of the top mines in Canada, Kazakhstan and Namibia.

So the rush of mining activity here serves as a testament to the magnitude of the uranium fever sweeping the globe right now. At just over $70 per pound, the price is up some 200% over the past five years — even after it gave back a chunk of its gains in 2024. The mining outfits that held claims to those old sites went from nearly worthless — mere penny stocks in most cases — to high-flyers on New York and Toronto exchanges.

Energy Fuels is valued at over $1 billion today, up some 500% from early 2020.

Mark Chalmers, the CEO at Energy Fuels, had watched the rally in uranium somewhat skeptically at first. But when the price suddenly pierced the $50 mark in 2022, after hovering right around $20 for years, it got his attention. “That’s when we seriously started looking to open” the mine, he says.

It was a chilly late fall morning and Chalmers, 67, was huddling with his lieutenants in the breakroom at the mine, a postage stamp of a spot carved out of a thick stand of pine trees. Deep down below, a small team was drilling holes into the sedimentary walls that snake through the mine. Chalmers had them searching for the very best ore. This way, they’d know where to begin when they finally got the green light to ship through Navajo territory.

At Pinyon Plain, they’re used to setbacks. Prospectors discovered the deposit in the 1970s but by the time all the mining permits were secured a decade later, the global uranium market had collapsed. Just like in 2011, the initial trigger was a nuclear disaster, the Chernobyl meltdown. And then, a few years later, the Berlin Wall fell and the nuclear arms race was over.

Plans were hatched over the years to open the mine as uranium prices bumped higher, but the enthusiasm would die as soon as the rally faded. It took the 2022 price surge to get Chalmers, who’s been scouting out Pinyon Plain ever since he first joined Energy Fuels back in the 1980s, to finally ram it through.

Now, after a single shipment to the mill in Utah, he’s stuck again. As he sees it, routes 89 and 160 are federal highways and, as a result, subject to federal shipping laws. The company doesn’t need the Navajos’ authorization, he says. To Nygren, every single inch of Navajo territory is subject to tribal law.

Back in the summer, Katie Hobbs, the governor of Arizona, urged the two men to sit down and work out a deal. Negotiations have proceeded slowly so far, though both sides say progress is being made.

Animosity towards mining companies runs high on Navajo land. It’s visible everywhere. On huge roadside billboards and small office signs, in fading pinks and yellows and jet blacks, too. They read “Radioactive Pollution Kills” and “Haul No” and, along the main entrance to Cameron, a hard-scrabble village on the territory’s western edge, “No Uranium Mining.”

A few miles down the road, big mounds of sand streaked gray and blue rise, one after the other, high above the vast desert landscape. They are the tailings from some of the uranium mines that were abandoned in the territory last century.

To Ray Yellowfeather, a 50-year-old construction worker, the tailings were always the “blue hills,” just one big playground for him and his childhood friends.

“We would climb up the blue hills and slide back down,” Yellowfeather says. “Nobody told us they were dangerous.”

Years later, they would be cordoned off by the Environmental Protection Agency as it began work to clean up the mines. By then, though, the damage was done. Like many around here, Yellowfeather says he’s lost several family members to stomach cancer. The last of them was his mother in 2022.

Yellowfeather admits he doesn’t know exactly what caused their cancer but, he says, “I have to think it has to do with the piles of radioactive waste all around us.” It’s in the construction material in many of the homes and buildings and in the aquifers, too. To this day, drinking water is shipped into some of the hardest-hit areas.

The US government has recognized the harm its nuclear arms projects have done to communities in the Southwest. In 1990, Congress passed a law to compensate victims who contracted cancer and other diseases. It paid out some $2.5 billion over the ensuing three decades. The EPA, meanwhile, has been in charge of the clean-up of the abandoned mines. Two decades after the program began, though, only a small percentage have been worked on at all.

This is giving mining companies an opportunity to curry favor in tribal communities by offering to take over and expedite the clean-up of some mines. Chalmers has made it a key point in negotiations with Nygren.

“It’s frankly appalling how little the EPA has done,” he says. “We can probably do more for the Navajo Nation than the EPA has done in its entirety.”

The EPA said it expects to accelerate the work. “EPA has completed shorter term cleanups at over 30 sites and has made significant progress toward comprehensive cleanups of abandoned uranium mines in the Navajo Nation,’’ it said in an e-mailed response to questions last week. “The Agency expects the pace of cleanups to increase as we continue to standardize the methods and approaches used to investigate and clean up sites.”

Weeks earlier, the EPA released a detailed study on Pinyon Plain. In it, the agency found that operations at the mine could contaminate the water supply of the Havasupai, a tribe tucked in such a remote corner of the Grand Canyon that it receives mail by mule. The report emboldened Havasupai leaders to step up their opposition to the mine, adding to Chalmers’s growing list of problems.

For the Navajo, the risks that come from the hauling of uranium through its territory are far smaller — so negligible as to be almost non-existent, according to Chalmers. Nygren is unmoved. The Navajo have heard such reassurances many times before, he says, only to pay dearly in the end.

Nygren grew up near a cluster of old mines right along the territory’s Arizona-Utah border, which makes the whole Energy Fuels affair “incredibly personal,” he says. His voice grows louder now and his tone more emphatic, indignant. To him, the Energy Fuels incursion feels no different than all the abuses committed over the course of decades by the US government and the mining companies that supplied it with a steady stream of uranium.

“We played a big role in the national security of the United States and we played a big part in the Cold War, providing energy for nuclear weapons. We’ve done our part. And now it’s time for the US to do its part by cleaning up these mines and respecting our laws.”

(By Jacob Lorinc)

No comments:

Post a Comment