Eid-al-Fitr

UN agency closes its remaining Gaza bakeries as food supplies dwindle under Israeli blockade

DEIR AL-BALAH, Gaza Strip (AP) — Israel, which later resumed its offensive to pressure the Hamas militant group into accepting changes to their ceasefire agreement, said enough food had entered Gaza during the six-week truce to sustain the territory's roughly 2 million Palestinians for a long time.

Sam Mednick and Wafaa Shurafa

April 3, 2025

DEIR AL-BALAH, Gaza Strip (AP) — The U.N. food agency is closing all of its bakeries in the Gaza Strip, officials said Tuesday, as supplies dwindle after Israel sealed off the territory from all imports nearly a month ago.

Israel, which later resumed its offensive to pressure the Hamas militant group into accepting changes to their ceasefire agreement, said enough food had entered Gaza during the six-week truce to sustain the territory’s roughly 2 million Palestinians for a long time.

U.N. spokesperson Stephane Dujarric said Israel’s assertion was “ridiculous,” calling the food shortage very critical. The organization is “at the tail end of our supplies” and a lack of flour and cooking oil are forcing the bakeries to close, Dujarric said Tuesday.

Markets largely emptied weeks ago. U.N. agencies say the supplies they built up during the truce are running out. Gaza is heavily reliant on international aid because the war has destroyed almost all of its food production capability.

Mohammed al-Kurd, a father of 12, said his children go to bed without dinner.

“We tell them to be patient and that we will bring flour in the morning,” he said. “We lie to them and to ourselves.”

For the second consecutive day, Israel’s military warned residents of Gaza’s southernmost city of Rafah to immediately evacuate, a sign that it could soon launch a major ground operation. At least 140,000 people were under orders to leave, according to the head of the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees.

Gaza’s bakeries shut down

A World Food Program memo circulated to aid groups said it could no longer operate its remaining bakeries, which produce the bread on which many rely. The U.N. agency said it was prioritizing its remaining stocks to provide emergency food aid and expand hot meal distribution. WFP spokespeople didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

Olga Cherevko, a spokesperson for the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, said WFP was closing its remaining 19 bakeries after shuttering six last month. She said hundreds of thousands of people relied on them.

The Israeli military body in charge of Palestinian affairs, known as COGAT, said more than 25,000 trucks entered Gaza during the ceasefire, carrying nearly 450,000 tons of aid. It said the amount represented around a third of what has entered during the war.

“There is enough food for a long period of time, if Hamas lets the civilians have it,” it said.

U.N. agencies and aid groups say they struggled to bring in and distribute aid before the ceasefire took hold in January. Their estimates for how much aid reached people in Gaza were consistently lower than COGAT’s, which were based on how much entered through border crossings.

Israeli strikes kill dozens

Gaza’s Health Ministry reported that at least 42 bodies and more than 180 wounded arrived at hospitals over the past 24 hours. At least 1,042 Palestinians have been killed in the two weeks since Israel broke the ceasefire and resumed heavy bombardments.

The war began when Hamas-led militants attacked southern Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, killing around 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and taking 251 hostages. Hamas is still holding 59 captives — 24 believed to be alive — after most of the rest were released in ceasefire agreements or other deals.

Israel’s offensive has killed more than 50,000 Palestinians, including hundreds killed in strikes since the ceasefire ended, according to Gaza’s Health Ministry, which doesn’t say whether those killed are civilians or combatants. Israel says it has killed around 20,000 militants, without providing evidence.

Israel sealed off Gaza from all aid at the start of the war but later relented under pressure from Washington. U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration, which took credit for helping to broker the ceasefire, has expressed full support for Israel’s actions, including its decision to end the truce.

Israel has demanded that Hamas release several hostages before further talks on ending the war. Those negotiations were supposed to begin in early February. It has also insisted that Hamas disarm and leave Gaza, conditions that weren’t part of the ceasefire agreement.

Hamas has called for implementing the agreement, in which the remaining hostages would be released in exchange for the release of more Palestinian prisoners, a lasting ceasefire and an Israeli withdrawal.

Palestinian journalist and family killed by Israeli strike

Palestinians mourned Mohamed Salah Bardawil, a journalist with Hamas-affiliated Aqsa Radio who was killed along with his wife and three children by an Israeli strike early Tuesday at their home in southern Gaza.

Associated Press footage showed the building in Khan Younis collapsed, with dried blood splattered on the rubble. A child’s school notebook, dust-covered dolls and clothing lay half-buried in the ruins. The Israeli military declined to comment.

The journalist is the nephew of Salah Bardawil, a well-known member of Hamas’ political bureau who was killed in an Israeli strike that also killed his wife last month.

Israeli strikes have killed more than 170 journalists and media workers since the war began, the Committee to Protect Journalists has estimated.

___

Mednick reported from Tel Aviv, Israel. Associated Press writers Fatma Khaled in Cairo and Edith M. Lederer at the United Nations contributed to this report.

___

Follow AP’s war coverage at https://apnews.com/hub/israel-hamas-war

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

DEIR AL-BALAH, Gaza Strip (AP) — Israel, which later resumed its offensive to pressure the Hamas militant group into accepting changes to their ceasefire agreement, said enough food had entered Gaza during the six-week truce to sustain the territory's roughly 2 million Palestinians for a long time.

Sam Mednick and Wafaa Shurafa

April 3, 2025

DEIR AL-BALAH, Gaza Strip (AP) — The U.N. food agency is closing all of its bakeries in the Gaza Strip, officials said Tuesday, as supplies dwindle after Israel sealed off the territory from all imports nearly a month ago.

Israel, which later resumed its offensive to pressure the Hamas militant group into accepting changes to their ceasefire agreement, said enough food had entered Gaza during the six-week truce to sustain the territory’s roughly 2 million Palestinians for a long time.

U.N. spokesperson Stephane Dujarric said Israel’s assertion was “ridiculous,” calling the food shortage very critical. The organization is “at the tail end of our supplies” and a lack of flour and cooking oil are forcing the bakeries to close, Dujarric said Tuesday.

Markets largely emptied weeks ago. U.N. agencies say the supplies they built up during the truce are running out. Gaza is heavily reliant on international aid because the war has destroyed almost all of its food production capability.

Mohammed al-Kurd, a father of 12, said his children go to bed without dinner.

“We tell them to be patient and that we will bring flour in the morning,” he said. “We lie to them and to ourselves.”

For the second consecutive day, Israel’s military warned residents of Gaza’s southernmost city of Rafah to immediately evacuate, a sign that it could soon launch a major ground operation. At least 140,000 people were under orders to leave, according to the head of the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees.

Gaza’s bakeries shut down

A World Food Program memo circulated to aid groups said it could no longer operate its remaining bakeries, which produce the bread on which many rely. The U.N. agency said it was prioritizing its remaining stocks to provide emergency food aid and expand hot meal distribution. WFP spokespeople didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

Olga Cherevko, a spokesperson for the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, said WFP was closing its remaining 19 bakeries after shuttering six last month. She said hundreds of thousands of people relied on them.

The Israeli military body in charge of Palestinian affairs, known as COGAT, said more than 25,000 trucks entered Gaza during the ceasefire, carrying nearly 450,000 tons of aid. It said the amount represented around a third of what has entered during the war.

“There is enough food for a long period of time, if Hamas lets the civilians have it,” it said.

U.N. agencies and aid groups say they struggled to bring in and distribute aid before the ceasefire took hold in January. Their estimates for how much aid reached people in Gaza were consistently lower than COGAT’s, which were based on how much entered through border crossings.

Israeli strikes kill dozens

Gaza’s Health Ministry reported that at least 42 bodies and more than 180 wounded arrived at hospitals over the past 24 hours. At least 1,042 Palestinians have been killed in the two weeks since Israel broke the ceasefire and resumed heavy bombardments.

The war began when Hamas-led militants attacked southern Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, killing around 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and taking 251 hostages. Hamas is still holding 59 captives — 24 believed to be alive — after most of the rest were released in ceasefire agreements or other deals.

Israel’s offensive has killed more than 50,000 Palestinians, including hundreds killed in strikes since the ceasefire ended, according to Gaza’s Health Ministry, which doesn’t say whether those killed are civilians or combatants. Israel says it has killed around 20,000 militants, without providing evidence.

Israel sealed off Gaza from all aid at the start of the war but later relented under pressure from Washington. U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration, which took credit for helping to broker the ceasefire, has expressed full support for Israel’s actions, including its decision to end the truce.

Israel has demanded that Hamas release several hostages before further talks on ending the war. Those negotiations were supposed to begin in early February. It has also insisted that Hamas disarm and leave Gaza, conditions that weren’t part of the ceasefire agreement.

Hamas has called for implementing the agreement, in which the remaining hostages would be released in exchange for the release of more Palestinian prisoners, a lasting ceasefire and an Israeli withdrawal.

Palestinian journalist and family killed by Israeli strike

Palestinians mourned Mohamed Salah Bardawil, a journalist with Hamas-affiliated Aqsa Radio who was killed along with his wife and three children by an Israeli strike early Tuesday at their home in southern Gaza.

Associated Press footage showed the building in Khan Younis collapsed, with dried blood splattered on the rubble. A child’s school notebook, dust-covered dolls and clothing lay half-buried in the ruins. The Israeli military declined to comment.

The journalist is the nephew of Salah Bardawil, a well-known member of Hamas’ political bureau who was killed in an Israeli strike that also killed his wife last month.

Israeli strikes have killed more than 170 journalists and media workers since the war began, the Committee to Protect Journalists has estimated.

___

Mednick reported from Tel Aviv, Israel. Associated Press writers Fatma Khaled in Cairo and Edith M. Lederer at the United Nations contributed to this report.

___

Follow AP’s war coverage at https://apnews.com/hub/israel-hamas-war

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Eid-al-Fitr begins with the images of Gaza’s children dressed in death

(RNS) — Eid is meant to be a day of celebration. But this year, it was also a day of mourning.

Relatives mourn 12-year-old Ahmad Abu Teir, who was killed in an Israeli army strike, before his funeral along with seven other Palestinians, including a father, mother, and their three children, on the first day of the Muslim holiday of Eid in Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, Sunday, March 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

Omar Suleiman

March 31, 202

(RNS) — Eid al-Fitr is supposed to be a day of joy marking the end of a month of spiritual striving, of fasting, prayer and giving. It’s the day when, after a month of self-denial, the entire community comes together — dressed in new clothes, exchanging gifts, embracing one another in celebration.

This year, joy was elusive.

On the morning of Eid, as we prepared to gather in prayer, news began to trickle in from Gaza. Children had been slaughtered — again. Multiple children had been bombed to death by Israeli airstrikes as the sun rose, ending their Eid excitement and their lives. One image in particular will not leave me: a child dressed in brand-new Eid clothes, now wrapped in a burial shroud clutching a toy with his lifeless hand. What was supposed to be a morning of sweets and celebration had become another chapter in a long, unending nightmare.

Just hours later, I stood at an Eid prayer in America, watching hundreds of children — my own included — running around in colorful outfits, holding new toys, laughing and hugging their friends. The sight should have filled me with joy, but the deaths of the children in Gaza made it almost unbearable.

I wasn’t alone. A doctor from my community in Dallas who is currently volunteering in Gaza messaged me with his own heartbreaking witness. “Today’s been the worst day by far. Bombing most intense at Fajr when people were getting ready for Eid. Children in their Eid clothes and jewelry are in the morgues.”

This is the backdrop against which Muslims around the world tried to celebrate.

What do we do with that kind of sorrow?

Islam teaches that Ramadan is a month of cultivating empathy. Eid is meant to continue that empathy, even into our celebrations. On the morning of Eid, every Muslim is required to pay Zakat al-Fitr — a form of charity designed to ensure that no one is left out of the feast. It is a beautiful practice: a way of saying that joy is only complete when shared, that our celebration is meaningless if others are starving.

How do we fulfill that responsibility when an entire population is being starved intentionally? The blockade on Gaza has made it nearly impossible to deliver aid. Humanitarian convoys are bombed, bakeries are destroyed, access to clean water and medicine is deliberately withheld. Zakat al-Fitr — the alms given by Muslims at this holy time — is supposed to feed the hungry. But in Gaza, even bread is a casualty of war.

And yet, amid the devastation, there was a moment that gave me hope.

A young boy named Adam, a survivor from Gaza receiving treatment here in the U.S., came up to me on Eid morning. He was hobbling on his new prosthetic leg — a reminder of what he had endured. But as he approached, he smiled wide and gave me a huge hug. In that moment, I thought about the children who didn’t survive and prayed that they were now embracing their loved ones in the gardens of paradise, celebrating a different kind of Eid — free from bombs, from fear, from sorrow.

And I prayed that those still with us, like Adam, can have a future that honors what they’ve been through — a future where they don’t have to trade limbs for safety or childhoods for survival.

Eid is meant to be a day of celebration. But this year, it was also a day of mourning. A day of tension between gratitude and grief. And in that tension, we find a deeper calling — not just to grieve, but to act. Not just to celebrate, but to remember.

Because joy, when denied to some, cannot be fully enjoyed by others.

And because children like Adam deserve more than our tears — they deserve a world that never again forces them to say goodbye before they’ve even had the chance to live.

Ohio group gathers personal letters to connect with Muslims in prison for Eid

(RNS) — Eid Letters to Incarcerated Muslims is one of several groups in America sending letters to incarcerated Muslims for the holiday and, ultimately, advocating for prison abolishment.

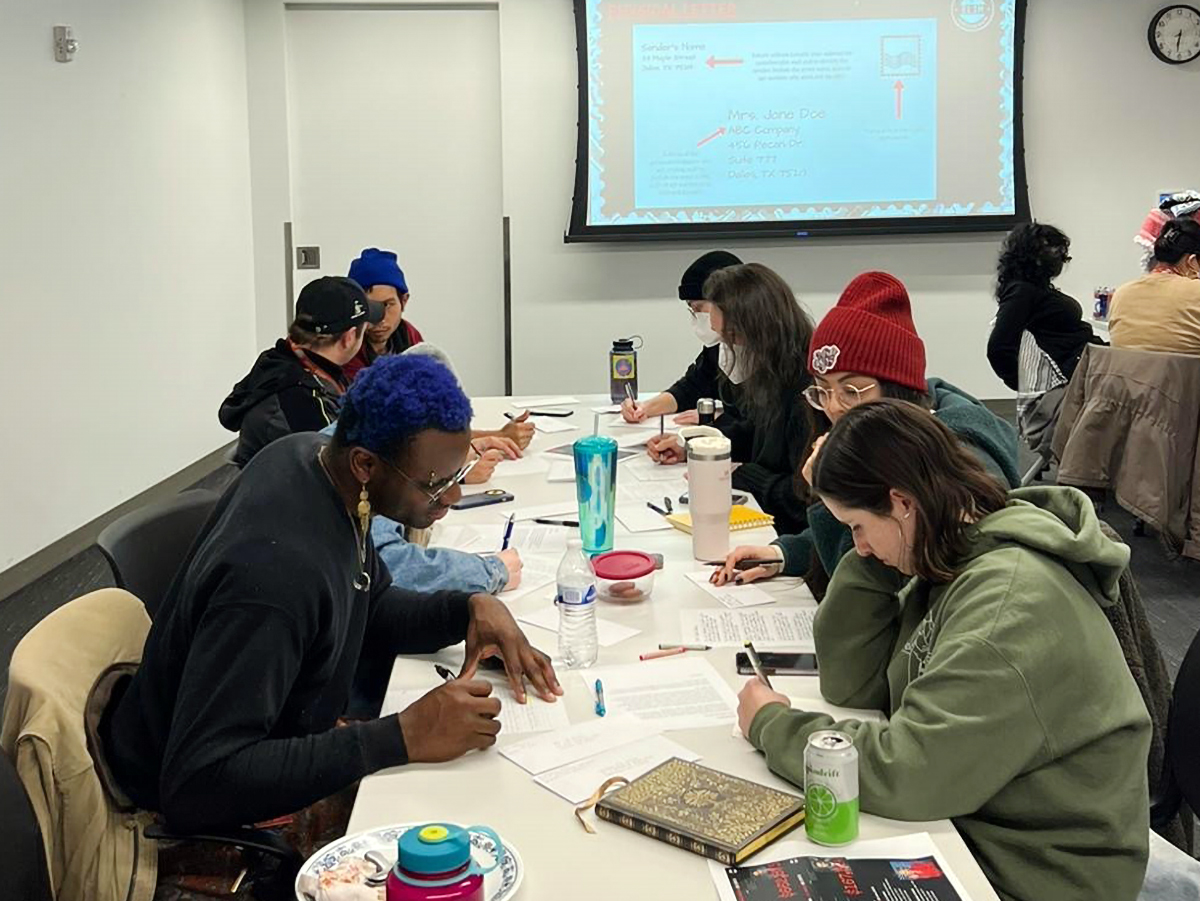

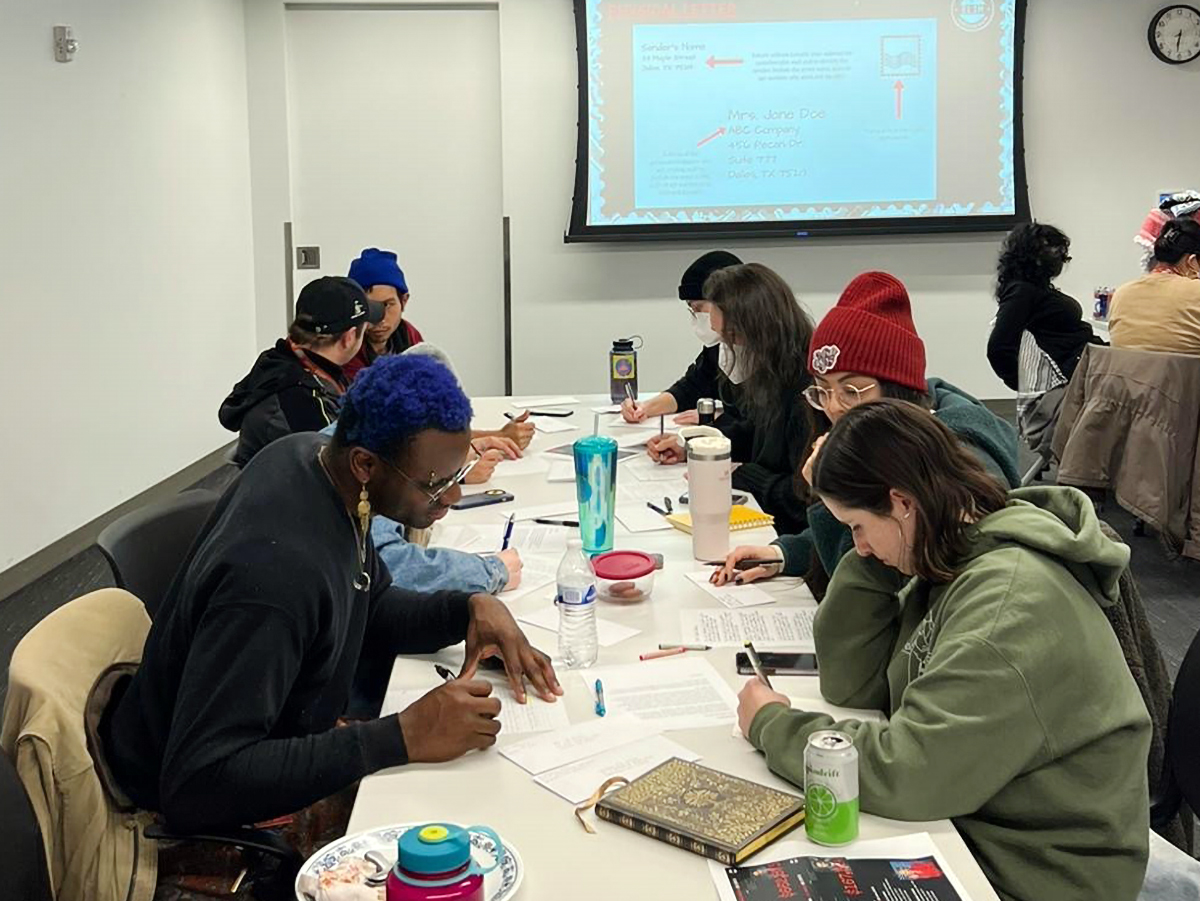

Volunteers in Ohio participate in an annual Eid Al-Fitr letter-writing campaign organized by Eid Letters to Incarcerated Muslims. (Photo courtesy ELIM)

Reina Coulibaly

March 31, 2025

(RNS) — Muslims in North America are celebrating Eid Al-Fitr, marking the end of the holy month of Ramadan. Around the world, people celebrate by donning their best attire, gathering for prayers and exchanging gifts.

For incarcerated Muslims, though, the holiday looks drastically different. While some can celebrate with other Muslims in their facility, many observe the holiday in isolation.

Earlier this month, Eid Letters to Incarcerated Muslims, an Ohio grassroots project that for the past five years has facilitated an annual Eid Al-Fitr letter-writing campaign for incarcerated Muslims in the state, hosted a webinar about its efforts.

The project aims to connect with incarcerated Muslims and sees advocacy for prison abolishment as an important part of practicing the Islamic faith, according to the group. To volunteers and leaders, letter writing is a form of advocacy work foundational to their spiritual and political commitments.

One of ELIM’s core organizers, Mariam Khan, sees the group’s work as a form of worship that follows in the example of the Prophet Muhammad.

“When I read about the Sunnah (the Prophet Muhammad’s recorded practices) and life of the Prophet, I see him as a community organizer, someone giving the clothes off his back and the money in his pocket to the most needy,” Khan said. “I want to create an Islamic practice that centers around action, around material change through our faith. That extends to our incarcerated brothers and sisters.”

RELATED: For Muslims with eating disorders, Ramadan fasting can present health and spiritual challenges

This year, ELIM volunteers gathered nearly 350 letters through community partnerships and writing events, like the annual webinar. The letters are being distributed to 230 men in two Ohio facilities: Lebanon Correctional Institution and the Ohio State Penitentiary. The recipients were identified through a “fasting roll call,” or a list of people who requested fasting accommodations provided to ELIM by facilities’ chaplains and other intermediaries.

ELIM is one of several faith-based groups across the country reaching those inside prisons through letter writing and resource distribution. Volunteer-run groups like the Philadelphia Muslim Freedom Fund, Sacramento Letters to Incarcerated Muslims and nonprofits like Believers Bail Out share a similar mission, also ultimately seeking prison abolishment. They run independently and focus on their respective locales.

Zumana Noor, a core leader for the Philadelphia Muslim Freedom Fund, said the group’s work is rooted in solidarity, not charity.

“It’s our duty as Muslims to support our brothers and sisters in need, including those behind bars,” Noor said. “That’s really the center of what we do. It’s about compassion, about giving back.”

A Philadelphia Muslim Freedom Fund letter-writing event on June 20, 2024. (Photo courtesy PMFF)

Noor also noted the often intangible impact of such outreach.

“When the system sees that someone is being cared for, that there are people checking in and mailing letters, they’re less likely to pull stuff with them,” Noor said. “They know there are people on the outside who will speak up.”

Kenza Kamal, one of ELIM’s founding members, emphasized that incarcerated Muslims have much to offer.

“The folks inside are highly learned,” Kamal said. “They study and know things that many of us on the outside have not had the focus, discipline or the pressure to learn.”

For ELIM organizers, letter writing is a way to connect with incarcerated people and send a message of hope for the future, with ending incarceration being the ultimate goal.

“Abolition isn’t separate from Islam,” said Ridha Nazir, a newer ELIM organizer. “It teaches us to stand with the oppressed and to never lose sight of justice and to act with mercy. When we write these letters for incarcerated Muslims, we’re doing more than just sending words on a page. We’re extending solidarity, we’re extending care, we’re extending the spiritual connection.”

RELATED: In Algiers, a youth-led gallery offers community through music during Ramadan

Moreover, Nazir said, the prison system “is designed to isolate, and disappear people,” to which Islam stands in contrast.

“For us, letter writing is an act of worship,” Nazir said.

However, the Ohio campaign has at least one new obstacle. A new policy from the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, effective Feb. 1, mandates all incoming letters be copied or scanned into an electronic format for delivery and the originals destroyed after 30 days. Inmates can no longer receive original — often handwritten — letters from ELIM.

Fardowsa Dahir, another ELIM organizer, said new restrictions seem to be implemented every year in the state. And, much communication getting into the facilities relies on one person, like an amenable imam or chaplain, Khan added.

“When that person stops communicating with us, that’s the end of our lifeline to administer and organize this project,” Khan said.

The new mail policy also affects the emotional weight of the letters, Nazir said, as the scanning process strips away some of the personal and spiritual intimacy that handwritten letters offer.

“We always want to work in the way of the Prophet (Muhammad), and we’re following the example he set,” Nazir said. “He never turned his back on those who are isolated or imprisoned or struggling. And so, we remember the Quranic verses that tell us to speak truth, to show up and to not be complicit to injustice through silence.”

This article was produced as part of the RNS/Interfaith America Religion Journalism Fellowship.

(RNS) — Eid Letters to Incarcerated Muslims is one of several groups in America sending letters to incarcerated Muslims for the holiday and, ultimately, advocating for prison abolishment.

Volunteers in Ohio participate in an annual Eid Al-Fitr letter-writing campaign organized by Eid Letters to Incarcerated Muslims. (Photo courtesy ELIM)

Reina Coulibaly

March 31, 2025

(RNS) — Muslims in North America are celebrating Eid Al-Fitr, marking the end of the holy month of Ramadan. Around the world, people celebrate by donning their best attire, gathering for prayers and exchanging gifts.

For incarcerated Muslims, though, the holiday looks drastically different. While some can celebrate with other Muslims in their facility, many observe the holiday in isolation.

Earlier this month, Eid Letters to Incarcerated Muslims, an Ohio grassroots project that for the past five years has facilitated an annual Eid Al-Fitr letter-writing campaign for incarcerated Muslims in the state, hosted a webinar about its efforts.

The project aims to connect with incarcerated Muslims and sees advocacy for prison abolishment as an important part of practicing the Islamic faith, according to the group. To volunteers and leaders, letter writing is a form of advocacy work foundational to their spiritual and political commitments.

One of ELIM’s core organizers, Mariam Khan, sees the group’s work as a form of worship that follows in the example of the Prophet Muhammad.

“When I read about the Sunnah (the Prophet Muhammad’s recorded practices) and life of the Prophet, I see him as a community organizer, someone giving the clothes off his back and the money in his pocket to the most needy,” Khan said. “I want to create an Islamic practice that centers around action, around material change through our faith. That extends to our incarcerated brothers and sisters.”

RELATED: For Muslims with eating disorders, Ramadan fasting can present health and spiritual challenges

This year, ELIM volunteers gathered nearly 350 letters through community partnerships and writing events, like the annual webinar. The letters are being distributed to 230 men in two Ohio facilities: Lebanon Correctional Institution and the Ohio State Penitentiary. The recipients were identified through a “fasting roll call,” or a list of people who requested fasting accommodations provided to ELIM by facilities’ chaplains and other intermediaries.

ELIM is one of several faith-based groups across the country reaching those inside prisons through letter writing and resource distribution. Volunteer-run groups like the Philadelphia Muslim Freedom Fund, Sacramento Letters to Incarcerated Muslims and nonprofits like Believers Bail Out share a similar mission, also ultimately seeking prison abolishment. They run independently and focus on their respective locales.

Zumana Noor, a core leader for the Philadelphia Muslim Freedom Fund, said the group’s work is rooted in solidarity, not charity.

“It’s our duty as Muslims to support our brothers and sisters in need, including those behind bars,” Noor said. “That’s really the center of what we do. It’s about compassion, about giving back.”

A Philadelphia Muslim Freedom Fund letter-writing event on June 20, 2024. (Photo courtesy PMFF)

Noor also noted the often intangible impact of such outreach.

“When the system sees that someone is being cared for, that there are people checking in and mailing letters, they’re less likely to pull stuff with them,” Noor said. “They know there are people on the outside who will speak up.”

Kenza Kamal, one of ELIM’s founding members, emphasized that incarcerated Muslims have much to offer.

“The folks inside are highly learned,” Kamal said. “They study and know things that many of us on the outside have not had the focus, discipline or the pressure to learn.”

For ELIM organizers, letter writing is a way to connect with incarcerated people and send a message of hope for the future, with ending incarceration being the ultimate goal.

“Abolition isn’t separate from Islam,” said Ridha Nazir, a newer ELIM organizer. “It teaches us to stand with the oppressed and to never lose sight of justice and to act with mercy. When we write these letters for incarcerated Muslims, we’re doing more than just sending words on a page. We’re extending solidarity, we’re extending care, we’re extending the spiritual connection.”

RELATED: In Algiers, a youth-led gallery offers community through music during Ramadan

Moreover, Nazir said, the prison system “is designed to isolate, and disappear people,” to which Islam stands in contrast.

“For us, letter writing is an act of worship,” Nazir said.

However, the Ohio campaign has at least one new obstacle. A new policy from the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, effective Feb. 1, mandates all incoming letters be copied or scanned into an electronic format for delivery and the originals destroyed after 30 days. Inmates can no longer receive original — often handwritten — letters from ELIM.

Fardowsa Dahir, another ELIM organizer, said new restrictions seem to be implemented every year in the state. And, much communication getting into the facilities relies on one person, like an amenable imam or chaplain, Khan added.

“When that person stops communicating with us, that’s the end of our lifeline to administer and organize this project,” Khan said.

The new mail policy also affects the emotional weight of the letters, Nazir said, as the scanning process strips away some of the personal and spiritual intimacy that handwritten letters offer.

“We always want to work in the way of the Prophet (Muhammad), and we’re following the example he set,” Nazir said. “He never turned his back on those who are isolated or imprisoned or struggling. And so, we remember the Quranic verses that tell us to speak truth, to show up and to not be complicit to injustice through silence.”

This article was produced as part of the RNS/Interfaith America Religion Journalism Fellowship.

No comments:

Post a Comment