‘Manipulated’ Alzheimer’s data may have misled research for 16 years

Sarah Knapton

Thu, July 21, 2022

Man points at brain scan images - David A White/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

The key theory of what causes Alzheimer’s disease may be based on ‘manipulated’ data which has misdirected dementia research for 16 years – potentially wasting billions of pounds – a major investigation suggests.

A six-month probe by the journal Science reported “shockingly blatant” evidence of result tampering in a seminal research paper which proposed Alzheimer’s is triggered by a build-up of amyloid beta plaques in the brain.

In the 2006 article from the University of Minnesota, published in the journal Nature, scientists claimed to have discovered a type of amyloid beta which brought on dementia when injected into young rats.

It was the first substance ever identified in brain tissue which could cause memory impairment, and seemed like a smoking gun.

The Nature paper became one of the most-cited scientific articles on Alzheimer’s ever published, sparking a huge jump in global funding for research into drugs to clear away the plaques.

But the Science investigation claims to have found evidence that images of amyloid beta in mice had been doctored, in allegations branded “extremely serious” by the charity Alzheimer’s Research UK.

Elizabeth Bik, a forensic image consultant, brought in to assess the images, told Science that the authors appeared to have pieced together parts of photos from different experiments.

“The obtained experimental results might not have been the desired results and that data might have been changed to … better fit a hypothesis,” she said.

‘Mislead an entire field of research’

Issues with the research were originally spotted by neuroscientist Dr Matthew Schrag of Vanderbilt University, Tennessee, who noticed anomalies while involved in a separate investigation into an experimental Alzheimer’s drug.

In a whistleblower report to the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), Dr Schrag warned that the research “has the potential to mislead an entire field of research”.

The journal Science looked separately into his claims, and said its own investigation “provided strong support for Schrag’s suspicions”.

Although the Minnesota authors stand by their research, the claims are now being studied by the NIH, who can choose to pass on the matter to the US Government’s Office of Research Integrity if deemed to be credible.

The journal Nature has also launched its own investigation and has placed a warning on the 2006 article urging readers to “use caution” when using the results.

If proven, such manipulation could mark one of the biggest scientific scandals since Dr Andrew Wakefield linked the MMR jab to autism in a 1988 Lancet article.

Plaques in the brain were first identified in dementia patients by the German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer in 1906, and in 1984 amyloid beta was found to be their main component.

For the next 20 years, hundreds of trials were conducted into therapies targeting amyloid in the brain, but all failed, leading to the theory being largely abandoned until the Minnesota paper was published in 2006.

Since then, universities, research institutions and pharmaceutical companies have spent billions investigating and trialling therapies to clear the brain of amyloid, but none have worked.

Dennis Selkoe, professor of neurologic diseases, at Harvard University, told Science that there was “precious little evidence” that the amyloid found by the Minnesota team even existed.

Professor Thomas Sudhof, a Nobel laureate of Stanford University, added: “The immediate, obvious damage, is wasted NIH funding and wasted thinking in the field because people are using these results as a starting point for their own experiments.”

The authors of the Minnesota paper have defended their original findings claiming they “still have faith” that amyloid play a major causative role in Alzheimer’s.

Amyloid itself not in question

Commenting on the findings, Dr Sara Imarisio, head of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, said: “These allegations are extremely serious. While we haven’t seen all of the published findings that have been called into question, any allegation of scientific misconduct needs to be investigated and dealt with where appropriate.

“Researchers need to be able to have confidence in the findings of their peers, so they can continue to make progress for people affected by diseases like dementia.

“The amyloid protein is at the centre of the most influential theory of how Alzheimer’s disease develops in the brain. But the research that has been called into question is focused on a very specific type of amyloid, and these allegations do not compromise the vast majority of knowledge built up during decades of research into the role of this protein in the disease.”

Dr Richard Oakley, associate director of research at Alzheimer’s Society, said: “There are many types of amyloid we know contribute to brain cell death in dementia. If what’s suggested here ends up being true we definitely would not need to throw the baby out with the bath water.”

Sarah Knapton

Thu, July 21, 2022

Man points at brain scan images - David A White/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

The key theory of what causes Alzheimer’s disease may be based on ‘manipulated’ data which has misdirected dementia research for 16 years – potentially wasting billions of pounds – a major investigation suggests.

A six-month probe by the journal Science reported “shockingly blatant” evidence of result tampering in a seminal research paper which proposed Alzheimer’s is triggered by a build-up of amyloid beta plaques in the brain.

In the 2006 article from the University of Minnesota, published in the journal Nature, scientists claimed to have discovered a type of amyloid beta which brought on dementia when injected into young rats.

It was the first substance ever identified in brain tissue which could cause memory impairment, and seemed like a smoking gun.

The Nature paper became one of the most-cited scientific articles on Alzheimer’s ever published, sparking a huge jump in global funding for research into drugs to clear away the plaques.

But the Science investigation claims to have found evidence that images of amyloid beta in mice had been doctored, in allegations branded “extremely serious” by the charity Alzheimer’s Research UK.

Elizabeth Bik, a forensic image consultant, brought in to assess the images, told Science that the authors appeared to have pieced together parts of photos from different experiments.

“The obtained experimental results might not have been the desired results and that data might have been changed to … better fit a hypothesis,” she said.

‘Mislead an entire field of research’

Issues with the research were originally spotted by neuroscientist Dr Matthew Schrag of Vanderbilt University, Tennessee, who noticed anomalies while involved in a separate investigation into an experimental Alzheimer’s drug.

In a whistleblower report to the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), Dr Schrag warned that the research “has the potential to mislead an entire field of research”.

The journal Science looked separately into his claims, and said its own investigation “provided strong support for Schrag’s suspicions”.

Although the Minnesota authors stand by their research, the claims are now being studied by the NIH, who can choose to pass on the matter to the US Government’s Office of Research Integrity if deemed to be credible.

The journal Nature has also launched its own investigation and has placed a warning on the 2006 article urging readers to “use caution” when using the results.

If proven, such manipulation could mark one of the biggest scientific scandals since Dr Andrew Wakefield linked the MMR jab to autism in a 1988 Lancet article.

Plaques in the brain were first identified in dementia patients by the German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer in 1906, and in 1984 amyloid beta was found to be their main component.

For the next 20 years, hundreds of trials were conducted into therapies targeting amyloid in the brain, but all failed, leading to the theory being largely abandoned until the Minnesota paper was published in 2006.

Since then, universities, research institutions and pharmaceutical companies have spent billions investigating and trialling therapies to clear the brain of amyloid, but none have worked.

Dennis Selkoe, professor of neurologic diseases, at Harvard University, told Science that there was “precious little evidence” that the amyloid found by the Minnesota team even existed.

Professor Thomas Sudhof, a Nobel laureate of Stanford University, added: “The immediate, obvious damage, is wasted NIH funding and wasted thinking in the field because people are using these results as a starting point for their own experiments.”

The authors of the Minnesota paper have defended their original findings claiming they “still have faith” that amyloid play a major causative role in Alzheimer’s.

Amyloid itself not in question

Commenting on the findings, Dr Sara Imarisio, head of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, said: “These allegations are extremely serious. While we haven’t seen all of the published findings that have been called into question, any allegation of scientific misconduct needs to be investigated and dealt with where appropriate.

“Researchers need to be able to have confidence in the findings of their peers, so they can continue to make progress for people affected by diseases like dementia.

“The amyloid protein is at the centre of the most influential theory of how Alzheimer’s disease develops in the brain. But the research that has been called into question is focused on a very specific type of amyloid, and these allegations do not compromise the vast majority of knowledge built up during decades of research into the role of this protein in the disease.”

Dr Richard Oakley, associate director of research at Alzheimer’s Society, said: “There are many types of amyloid we know contribute to brain cell death in dementia. If what’s suggested here ends up being true we definitely would not need to throw the baby out with the bath water.”

By Judy Packer-Tursman

UPI

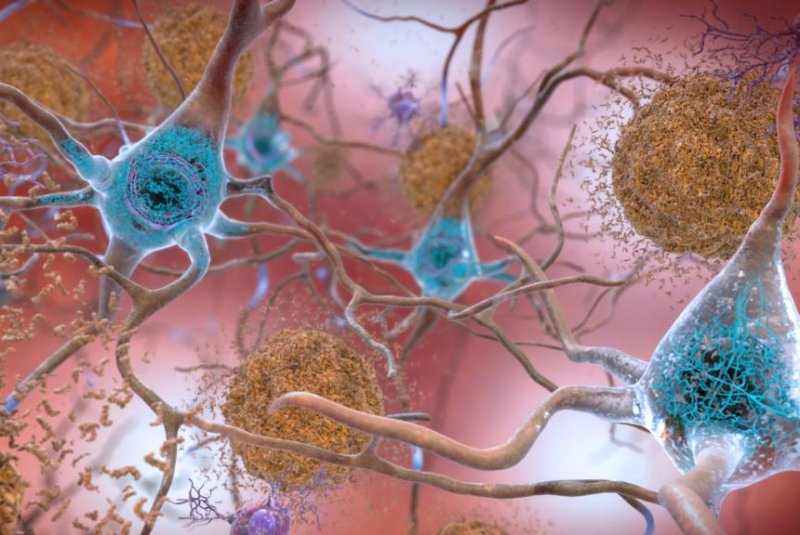

Beta-amyloid plaques and tau in the brain are two hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease, a topic spurring much research and some questions about scientific integrity.

Photo courtesy of National Institute on Aging/NIH

WASHINGTON, July 21 (UPI) -- A probe by a prestigious science journal, published Thursday, raises questions about the integrity of some Alzheimer's disease research, including scientific evidence that helped launch an investigational drug into large, ongoing clinical trials.

The probe, which examined research into Cassava Sciences' lead Alzheimer's drug candidate, simufilam, was published in the American Association for the Advancement of Science's peer-reviewed academic journal, Science.

A range of Alzheimer's research -- particularly related to simufilam -- has been under dogged scrutiny by scientists, medical journals and some researchers' own institutions. The Food and Drug Administration has been asked to intervene.

It's a complex tale of medical intrigue, whistleblowers and accusations of faulty and deceptive research amid hope that scientists can make large strides in combatting Alzheimer's debilitating effects.

WASHINGTON, July 21 (UPI) -- A probe by a prestigious science journal, published Thursday, raises questions about the integrity of some Alzheimer's disease research, including scientific evidence that helped launch an investigational drug into large, ongoing clinical trials.

The probe, which examined research into Cassava Sciences' lead Alzheimer's drug candidate, simufilam, was published in the American Association for the Advancement of Science's peer-reviewed academic journal, Science.

A range of Alzheimer's research -- particularly related to simufilam -- has been under dogged scrutiny by scientists, medical journals and some researchers' own institutions. The Food and Drug Administration has been asked to intervene.

It's a complex tale of medical intrigue, whistleblowers and accusations of faulty and deceptive research amid hope that scientists can make large strides in combatting Alzheimer's debilitating effects.

RELATED Greater risk of Alzheimer's may be linked to gut disorders, cholesterol, study says

As part of its probe, Science asked Elisabeth Bik, a California-based scientific integrity consultant, to serve as one of two independent image analysts.

She reviewed the findings of Dr. Matthew Schrag, a physician and neuroscientist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, who had explored potential errors in some Alzheimer's research by fellow neuroscientist Sylvain Lesné.

Lesné is a neuroscientist at the University of Minnesota.

Bik found Schrag's conclusions about possible image manipulation by Lesné in some of his research papers "compelling and sound," the magazine said.

Bik told UPI in an email she also has "serious concerns" about published research papers on simufilam from the Cassava-linked lab of Hoau-Yan Wang, an associate medical professor at the City University New York School of Medicine.

"It appears that some figures and other data from the Wang lab at CUNY, where Cassava's preclinical -- and some clinical -- work has been done, might have been falsified," Bik said.

RELATED One protein seen as 'critical factor' in development of Alzheimer's disease

Specifically, Bik questioned the Wang lab's presentation of "Western blots," used to detect Alzheimer's disease.

"Without public access to most original photos or data, it is hard to know what has really transpired," she said, "but the few purported original images that have been publicly shared appear to have been Photoshopped."

Remi Barbier, Cassava's president and CEO, told UPI in an email Wednesday, "It should go without saying that Cassava Sciences denies any and all allegations of wrongdoing. Any indication or inference that Cassava Sciences has engaged in any sort of misconduct is simply not true."

Jay Mwamba, CUNY's publications editorial manager, said the university "takes accusations of research misconduct very seriously" and its research integrity officer follows a specified policy after an accusation to determine whether misconduct occurred.

"While we cannot comment further at this time, we also recognize there is external interest in this process and where we can keep the public informed, we will," Mwamba told UPI in an email.

Vanderbilt's Schrag is the whistleblower whose expert findings led to Science's six-month investigation, according to AAAS.

Schrag said in the Science article his major concern is that the research by Cassava-linked scientists may be misleading and slow the race to find effective treatments for the neurodegenerative disease.

Neither Schrag nor Vanderbilt University Medical Center responded to UPI's requests for comment.

Yet, AAAS said in a news release summarizing the findings that the Science investigation "has found strong support for Schrag's suspicions, calling into question key lines of research in the quest to understand and treat Alzheimer's."

Schrag told Science that he sees "red flags" in some simufilam research by Cassava-linked scientists and broader Alzheimer's studies by Lesné, some of which were co-authored by Lesné's mentor, Karen Ashe.

"The university is aware that questions have arisen regarding certain images used in peer-reviewed research publications authored by university faculty Karen Ashe and Sylvain Lesné," Jake Ricker, a University of Minnesota spokesman, told UPI in an email Wednesday.

"The university will follow its processes to review the questions any claims have raised. At this time, we have no further information to provide," Ricker said. He confirmed that Lesné and Ashe "are currently university employees."

Schrag's deep dig began last summer when he was asked by Jordan A. Thomas, a Washington-based attorney with the law firm Labaton Sucharow, to investigate simufilam research findings to see whether he could spot any perceived irregularities.

Science describes Thomas's clients as "two prominent neuroscientists" concerned about the potential risks of simufilam without shown benefit.

Looking at published images related to simufilam, Schrag identified what Science describes as "apparently altered or duplicated images in dozens of journal articles."

Schrag doesn't use the word "fraud" or claim to have proven misconduct, according to Science, because such an assessment would "require access to original, complete and unpublished images and in some cases raw numerical data."

Aided by Schrag's work, Thomas filed a "statement of concern" last August with the Food and Drug Administration about the "accuracy and integrity" of data supporting ongoing clinical evaluation of simufilam.

It raised concerns about clinical biomarker data, "Western blot" analyses and analyses involving human brain tissue.

Thomas also filed a citizen petition alleging "grave concerns about the quality and integrity" of studies related to simufilam and its efficacy. He declined further comment in a phone call with UPI.

In February, the FDA dismissed the petition, which sought to halt clinical trials of simufilam. The drug agency said its decision was partly based on the petitioners' request that the agency "initiate an investigation," which is outside its scope of possible actions.

But, the FDA said, "We take the issues you raise seriously." The agency did not return UPI's requests for comment.

Meanwhile, Alzheimer's research has continued apace. Much of it centers on beta-amyloid, a protein that collects to form plaques in the brains of people with the disease -- the subject of Lesné's work.

This focus on reducing amyloid plaques, and figuring out how the tau protein contributes to Alzheimer's development, is seen by many as key to potential treatments.

"I think of amyloid as the fuse and tau as the bomb," Dr. Glen R. Finney, a professor of neurology at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine and director of the Geisinger Health Memory and Cognition Program, told UPI in a phone interview Wednesday.

While there are nearly 150 Alzheimer's drug candidates in the pipeline, Finney said the disease develops slowly, so finding a safe and effective treatment may take a decade.

In June 2021, the FDA gave accelerated approval to Biogen's infused monoclonal antibody drug Aduhelm (aducanumab), the first new Alzheimer's drug since 2003 and the first targeting amyloid beta plaques.

Cassava's drug candidate simufilam, an oral tablet, is taking a different approach, trying to stabilize a protein in the brain, altered filamin A, to improve cognitive functioning.

"With Alzheimer's, it seems that conventional science -- which has failed repeatedly -- continues to be met with optimism, while new approaches are attacked," Cassava's Barbier said. "I find this perplexing. There is an urgency to develop safe and effective treatments for people with Alzheimer's."

Finney said this "is a tough nut to crack" since "a lot of people [are] hungry for hope and sometimes that may lead to science not as strong being promoted."

Finney conceded "scientists are people, too, and may take shortcuts," necessitating institutional review boards and the need to replicate results in multiple labs.

However, he said, "The bigger problem isn't people massaging data. It is being careful we're not looking at studies with rose-colored glasses" and avoiding narrow research.

"It is not a time to despair or a time to pull back on Alzheimer's [research]," he said. "We need to have a 'moon shot' and accelerate it."

No comments:

Post a Comment