June 14, 2025

Frontiers

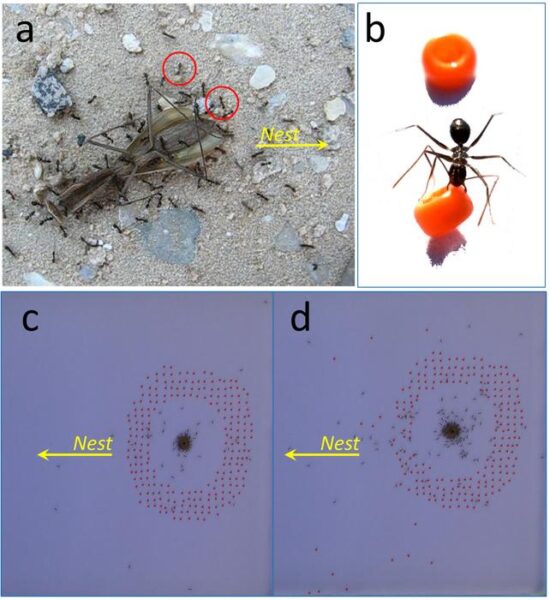

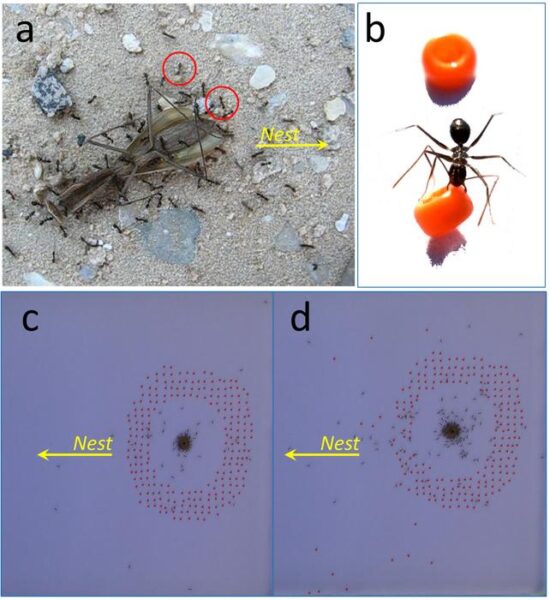

Examples of experimental set-up and close-up of collective transport of prey and of obstacle-clearing behavior

Examples of experimental set-up and close-up of collective transport of prey and of obstacle-clearing behavior

Scientists have discovered that longhorn crazy ants operate like miniature highway departments, clearing obstacles from roads before their teammates even arrive with bulky cargo.

The finding reveals how collective intelligence emerges from creatures whose brains contain fewer neurons than a human thumb has cells.

When these ants work together to haul large food items back to their nest, some workers sprint ahead to remove pebbles and debris from the anticipated path. It’s the first time researchers have documented such forward-looking behavior during cooperative transport in any ant species.

“Here we show for the first time that workers of the longhorn crazy ant can clear obstacles from a path before they become a problem – anticipating where a large food item will need to go and preparing the way in advance,” said Dr Ehud Fonio, a research fellow at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and corresponding author of the study published in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience.

The finding reveals how collective intelligence emerges from creatures whose brains contain fewer neurons than a human thumb has cells.

When these ants work together to haul large food items back to their nest, some workers sprint ahead to remove pebbles and debris from the anticipated path. It’s the first time researchers have documented such forward-looking behavior during cooperative transport in any ant species.

“Here we show for the first time that workers of the longhorn crazy ant can clear obstacles from a path before they become a problem – anticipating where a large food item will need to go and preparing the way in advance,” said Dr Ehud Fonio, a research fellow at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and corresponding author of the study published in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience.

Highway Engineering Without Engineers

The discovery happened by chance when researchers noticed individual ants picking up tiny gravel pebbles near groups carrying large insect prey. What seemed like random housekeeping turned out to be sophisticated logistics.

“When we first saw ants clearing small obstacles ahead of the moving load we were in awe. It appeared as if these tiny creatures understand the difficulties that lie ahead and try to help their friends in advance,” said Dr Ofer Feinerman, a professor at the Weizmann Institute.

But appearances can deceive. Through 83 carefully controlled experiments, the team discovered something even more remarkable than individual foresight: the ants were responding to chemical signals without understanding the bigger picture.

The clearing crews focus their efforts about 40 millimeters from food sources, specifically targeting the route back to the nest. They carry obstacles roughly 50 millimeters before dropping them away from the main highway. One particularly industrious ant cleared 64 obstacles in succession – a record that would impress any road crew supervisor.

Chemical Triggers and Traffic Management

The key breakthrough came when researchers realized that obstacle-clearing behavior depends entirely on pheromone trails – chemical breadcrumbs that recruiting ants leave behind. These scent marks, deposited every 0.2 seconds as ants run back to alert their sisters about food discoveries, serve as the trigger mechanism.

When researchers examined 155 cases of ants encountering obstacles, they found that 97.2% of clearing decisions happened only when fresh pheromone marks were nearby. Ants that couldn’t detect these chemical signals simply walked around obstacles instead of removing them.

The behavior proves remarkably context-sensitive. When researchers offered the same food type in small crumbs that individual ants could carry alone, clearing activity dropped dramatically. The ants cleared 32 times fewer obstacles and moved them much shorter distances when cooperative transport wasn’t needed.

Even more telling: ants cleared obstacles in response to pheromone trails even when no large food load existed. This happened when researchers introduced tuna oil that triggered exceptionally high recruitment responses, with 89.5% of arriving ants leaving pheromone marks.

Distributed Intelligence in Action

Perhaps most surprising is what the ants don’t know. Nearly half of the clearing crews never actually touched the food they were helping to transport. Some cleared obstacles without ever coming close to the cargo.

“Taken together, these results imply that our initial impression was wrong: in reality, individual workers don’t understand the situation at all. This intelligent behavior happens at the level of the colony, not the individual,” concluded Dr Danielle Mersch, formerly a postdoctoral researcher at the institute.

The research reveals how simple rules can generate complex, seemingly planned behavior. Each ant follows basic chemical cues without grasping the overall strategy, yet together they create efficient transportation networks.

Beyond Simple Reflexes

The obstacle-clearing dramatically improves efficiency. When researchers blocked narrow passages with plastic beads, transport time increased 18-fold compared to clear corridors. The ants had to remove most obstacles before their cargo could pass through.

Individual ants carrying small food items, however, experienced minimal delays from the same obstacles – they simply navigated around them. This suggests the clearing behavior specifically evolved to support group transport of oversized loads.

The timing also matters. Obstacle clearing occurs within minutes of food discovery, much faster than the days-long trail maintenance documented in other ant species. About 25% of clearing ants become repeat performers, systematically working the same sectors around food sources.

“Humans think ahead by imagining future events in their minds; ants don’t do that. But by interacting through chemical signals and shared actions, ant colonies can behave in surprisingly smart ways – achieving tasks that look planned, even though no single ant is doing the planning,” Feinerman explained.

The findings offer insights into how distributed intelligence systems can solve complex problems without central coordination. From robotic swarms to traffic management algorithms, understanding how simple agents create sophisticated group behaviors could influence engineering approaches that don’t rely on top-down control.

For the longhorn crazy ants, whose individual brains contain only 0.25 to 1 million neurons compared to humans’ 86 billion, collective intelligence proves that sometimes the whole truly exceeds the sum of its parts.

Ants Do Poop and They Even Use Toilets to Fertilize Their Own Gardens

Do ants poop? Discover how these social insects have developed ingenious methods to manage their waste.

By Avery Hurt

Jun 14, 2025

(Image Credit: Michael Siluk/Shutterstock)

Key Takeaways on Ant Poop

Do ants poop? Yes. Any creature that eats will poop and ants are no exception.

Because ants live in close quarters, they need to protect the colony from their feces so bacteria and fungus doesn't infect their health. This is why they use toilet chambers.

Whether they isolate it in a toilet chamber or kick it to the curb, ants don’t keep their waste around. But some ants find a use for that stuff. One such species is the leafcutter ant that takes little clippings of leaves and uses these leaves to grow a very particular fungus that they then eat.

Like urban humans, ants live in close quarters. Ant colonies can be home to thousands, even tens of thousands of individuals, depending on the species. And like any creature that eats, ants poop. When you combine close quarters and loads of feces, you have a recipe for disease, says Jessica Ware, curator and division chair of Invertebrate Zoology at the American Museum of Natural History.

“Ant poop can harbor bacteria, and because it contains partly undigested food, it can grow bacteria and fungus that could threaten the health of the colony,” Ware says.

But ant colonies aren’t seething beds of disease. That’s because ants are scrupulous about hygiene.

Ants Do Poop and Ant Toilets Are Real

Ant colony underground with ant chambers. (Image Credit: Lidok_L/Shutterstock)

To keep themselves and their nests clean, ants have evolved some interesting housekeeping strategies. Some types of ants actually have toilets — or at least something we might call toilets.

Their nests are very complicated, with lots of different tunnels and chambers, explains Ware, and one of those chambers is a toilet chamber. Ants don’t visit the toilet when they feel the call of nature. Instead, worker ants who are on latrine duty collect the poop and carry it to the toilet chamber, which is located far away from other parts of the nest.

Read More: Ants May Amputate Other Ants to Save Them – Is This a Sign of Empathy?

What Does Ant Poop Look Like?

This isn’t as messy a chore as it sounds. Like most insects, ants are water-limited, says Ware, so they try to get as much liquid out of their food as possible. This results in small, hard, usually black or brownish pellets of poop. The poop is dry and hard enough so that for ant species that don’t have indoor toilet chambers, the workers can just kick the poop out of the nest.

Ants Use Poop as Fertilizer

Whether they isolate it in a toilet chamber or kick it to the curb, ants don’t keep their waste around. Well, at least most types of ants don’t. Some ants find a use for that stuff. One such species is the leafcutter ant.

“They basically take little clippings of leaves and use these leaves to grow a very particular fungus that they then eat,” says Ware. “They don't eat the leaves, they eat the fungus.” And yep, they use their poop to fertilize their crops. “They’re basically gardeners,” Ware says.

If you’d like to see leafcutter ants at work in their gardens and you happen to be in the New York City area, drop by the American Museum of Natural History. They have a large colony of fungus-gardening ants on display.

Other Insects That Use Toilets

Ants may have toilets, but termites have even wilder ways of dealing with their wastes.

Termites and ants might seem similar at first sight, but they aren’t closely related. Ants are more closely related to bees, while termites are more closely related to cockroaches, explains Aram Mikaelyan, an entomologist at North Carolina State University who studies the co-evolution of insects and their gut microbiomes. So ants’ and termites’ styles of social living evolved independently, and their solutions to the waste problem are quite different.

“Termites have found a way to not distance themselves from the feces,” says Mikaelyan. “Instead, they use the feces itself as building material.”

They’re able to do this because they feed on wood, Mikaelyan explains. When wood passes through the termites’ digestive systems into the poop, it enables a type of bacteria called Actinobacteria. These bacteria are the source of many antibiotics that humans use. (Leafcutter ants also use Actinobacteria to keep their fungus gardens free of parasites.) So that unusual building material acts as a disinfectant. Mikaelyan describes it as “a living disinfectant wall, like a Clorox wall, almost.”

Insect Hygiene

It may seem surprising that ants and termites are so tidy and concerned with hygiene, but it’s really not uncommon.

“Insects in general are cleaner than we think,” says Ware. “We often think of insects as being really gross, but most insects don’t want to lie in their own filth.”

Read More: An Ancient Ant Army Once Raided Europe 35 Million Years Ago

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

The American Society of Microbiology. The Leaf-cutter Ant’s 50 Million Years of Farming

Avery Hurt is a freelance science journalist. In addition to writing for Discover, she writes regularly for a variety of outlets, both print and online, including National Geographic, Science News Explores, Medscape, and WebMD. She’s the author of Bullet With Your Name on It: What You Will Probably Die From and What You Can Do About It, Clerisy Press 2007, as well as several books for young readers. Avery got her start in journalism while attending university, writing for the school newspaper and editing the student non-fiction magazine. Though she writes about all areas of science, she is particularly interested in neuroscience, the science of consciousness, and AI–interests she developed while earning a degree in philosophy.

Do ants poop? Discover how these social insects have developed ingenious methods to manage their waste.

By Avery Hurt

Jun 14, 2025

DISCOVER

(Image Credit: Michael Siluk/Shutterstock)

Key Takeaways on Ant Poop

Do ants poop? Yes. Any creature that eats will poop and ants are no exception.

Because ants live in close quarters, they need to protect the colony from their feces so bacteria and fungus doesn't infect their health. This is why they use toilet chambers.

Whether they isolate it in a toilet chamber or kick it to the curb, ants don’t keep their waste around. But some ants find a use for that stuff. One such species is the leafcutter ant that takes little clippings of leaves and uses these leaves to grow a very particular fungus that they then eat.

Like urban humans, ants live in close quarters. Ant colonies can be home to thousands, even tens of thousands of individuals, depending on the species. And like any creature that eats, ants poop. When you combine close quarters and loads of feces, you have a recipe for disease, says Jessica Ware, curator and division chair of Invertebrate Zoology at the American Museum of Natural History.

“Ant poop can harbor bacteria, and because it contains partly undigested food, it can grow bacteria and fungus that could threaten the health of the colony,” Ware says.

But ant colonies aren’t seething beds of disease. That’s because ants are scrupulous about hygiene.

Ants Do Poop and Ant Toilets Are Real

Ant colony underground with ant chambers. (Image Credit: Lidok_L/Shutterstock)

To keep themselves and their nests clean, ants have evolved some interesting housekeeping strategies. Some types of ants actually have toilets — or at least something we might call toilets.

Their nests are very complicated, with lots of different tunnels and chambers, explains Ware, and one of those chambers is a toilet chamber. Ants don’t visit the toilet when they feel the call of nature. Instead, worker ants who are on latrine duty collect the poop and carry it to the toilet chamber, which is located far away from other parts of the nest.

Read More: Ants May Amputate Other Ants to Save Them – Is This a Sign of Empathy?

What Does Ant Poop Look Like?

This isn’t as messy a chore as it sounds. Like most insects, ants are water-limited, says Ware, so they try to get as much liquid out of their food as possible. This results in small, hard, usually black or brownish pellets of poop. The poop is dry and hard enough so that for ant species that don’t have indoor toilet chambers, the workers can just kick the poop out of the nest.

Ants Use Poop as Fertilizer

Whether they isolate it in a toilet chamber or kick it to the curb, ants don’t keep their waste around. Well, at least most types of ants don’t. Some ants find a use for that stuff. One such species is the leafcutter ant.

“They basically take little clippings of leaves and use these leaves to grow a very particular fungus that they then eat,” says Ware. “They don't eat the leaves, they eat the fungus.” And yep, they use their poop to fertilize their crops. “They’re basically gardeners,” Ware says.

If you’d like to see leafcutter ants at work in their gardens and you happen to be in the New York City area, drop by the American Museum of Natural History. They have a large colony of fungus-gardening ants on display.

Other Insects That Use Toilets

Ants may have toilets, but termites have even wilder ways of dealing with their wastes.

Termites and ants might seem similar at first sight, but they aren’t closely related. Ants are more closely related to bees, while termites are more closely related to cockroaches, explains Aram Mikaelyan, an entomologist at North Carolina State University who studies the co-evolution of insects and their gut microbiomes. So ants’ and termites’ styles of social living evolved independently, and their solutions to the waste problem are quite different.

“Termites have found a way to not distance themselves from the feces,” says Mikaelyan. “Instead, they use the feces itself as building material.”

They’re able to do this because they feed on wood, Mikaelyan explains. When wood passes through the termites’ digestive systems into the poop, it enables a type of bacteria called Actinobacteria. These bacteria are the source of many antibiotics that humans use. (Leafcutter ants also use Actinobacteria to keep their fungus gardens free of parasites.) So that unusual building material acts as a disinfectant. Mikaelyan describes it as “a living disinfectant wall, like a Clorox wall, almost.”

Insect Hygiene

It may seem surprising that ants and termites are so tidy and concerned with hygiene, but it’s really not uncommon.

“Insects in general are cleaner than we think,” says Ware. “We often think of insects as being really gross, but most insects don’t want to lie in their own filth.”

Read More: An Ancient Ant Army Once Raided Europe 35 Million Years Ago

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

The American Society of Microbiology. The Leaf-cutter Ant’s 50 Million Years of Farming

Avery Hurt is a freelance science journalist. In addition to writing for Discover, she writes regularly for a variety of outlets, both print and online, including National Geographic, Science News Explores, Medscape, and WebMD. She’s the author of Bullet With Your Name on It: What You Will Probably Die From and What You Can Do About It, Clerisy Press 2007, as well as several books for young readers. Avery got her start in journalism while attending university, writing for the school newspaper and editing the student non-fiction magazine. Though she writes about all areas of science, she is particularly interested in neuroscience, the science of consciousness, and AI–interests she developed while earning a degree in philosophy.

No comments:

Post a Comment