Eiffel Closes €1.2 Billion Fund to Accelerate Europe’s Energy Transition

Eiffel Investment Group has completed fundraising for its latest energy-transition infrastructure debt vehicle, Eiffel Energy Transition III, hitting its €1.2 billion hard cap and surpassing an initial €1 billion target.

The new fund marks the largest vintage in Eiffel’s energy-transition program and underscores accelerating capital demand for renewable energy across Europe. The strategy provides short-term, flexible debt to renewable developers, bridging a financing gap between costly equity and slower-moving long-term project finance—an area where infrastructure investors see rising structural imbalance.

Nearly half of commitments came from institutions that backed Eiffel’s previous two funds, highlighting the program’s performance and investor confidence. More than 30 major French and international investors joined the round, many seeking exposure to stable, collateralized green-energy assets at a moment when Europe faces record financing needs to meet decarbonization and energy sovereignty goals.

Since launching its first fund in 2017, Eiffel has financed more than 5,000 renewable assets—solar, wind, biomass, biogas, hydro, cogeneration, and efficiency projects—equivalent to 15 GW of low-carbon capacity. The firm has supported over 100 developers across Europe, helping accelerate project deployment in markets where permitting and capital constraints often delay build-out. Recent financings include solar portfolios in Ireland and Germany with Power Capital Renewable Energy and Enerparc.

Eiffel Energy Transition III is expected to deploy roughly €3 billion over its eight-year life thanks to recycling of repaid capital. The firm reports a €1.5 billion pipeline and reviewed over €7 billion in opportunities across 2024–2025. More than half of upcoming financings involve repeat borrowers, reflecting long-term relationships and larger-scale project ambitions.

The company has also expanded its infrastructure investment team to more than 30 professionals, adding four senior hires in 2025 to manage the accelerated deployment pace and portfolio oversight.

By Charles Kennedy for Oilprice.com

Europe Fast-Tracks Industrial Electrification With €1B Auction

- The EU has launched its first-ever industrial electrification auction, offering €1 billion in subsidies to replace fossil-fueled process heat with electric and renewable systems.

- Electrification is pulling ahead of hydrogen and CCS, as heat pumps, electric boilers, and similar technologies can be installed quickly.

- This auction marks a deeper shift in EU industrial policy.

The European Commission’s announcement of the first-ever EU-wide industrial electrification auction marks more than a new funding mechanism; it represents a philosophical shift in how Europe intends to decarbonize its industries, and a signal that, at least for now, electrons are pulling ahead of molecules in the energy transition race.

With a budget of €1 billion under the Innovation Fund, the pilot auction will subsidize the direct electrification of industrial process heat, one of the most stubborn and carbon-intensive parts of the industrial value chain. This is the world’s first auction of its kind, and its implications stretch far beyond factory walls.

Electrifying the hardest heat

Process heat is the silent giant of industrial emissions. It powers furnaces, reactors, dryers, and kilns in sectors ranging from steel and cement to chemicals, glass, and food production. It accounts for roughly one quarter of Europe’s industrial CO2 footprint, yet remains largely fossil-fueled.

The new auction directly targets that problem. Eligible technologies include industrial heat pumps, electric boilers, resistance and induction systems, plasma torches, as well as solar thermal and geothermal systems. In essence, it opens the door for any system that replaces fossil heat with clean electricity or direct renewable heat.

Projects will compete for a fixed premium subsidy per tonne of CO2 abated, paid for up to five years. This results-based model rewards measurable carbon reduction rather than theoretical potential, an important distinction. By tying payments to verified performance, the EU hopes to attract bankable projects and bridge the economic gap between conventional and electrified heat.

The auction is expected to open in December 2025, giving the industry a year to configure systems, partnerships, and monitoring plans. That may sound distant, but in industrial planning terms, it is the blink of an eye.

A test of scale and speed

The significance of this auction goes beyond the €1 billion headline. It signals that electrification has matured from an efficiency measure to a pillar of industrial decarbonization policy.

While Europe has spent years debating hydrogen backbones, carbon capture networks, and cross-border CO2 storage, electrification is quietly emerging as the fastest-moving front. The technologies exist, the supply chains are mostly domestic, and the emissions benefits are immediate.

Industrial heat pumps and electric boilers can be installed within existing plants, often with minimal permitting. They integrate naturally with renewables and with the grid, especially when paired with flexibility measures that shift demand away from peak hours. In a system increasingly constrained by intermittency, these grid-friendly industrial assets are valuable not only for emissions reduction but for balancing electricity supply and demand.

Related: French Major TotalEnergies Scales Up North Sea Operations

By contrast, molecule-based pathways such as hydrogen, synthetic fuels, or CCS remain hampered by high costs, infrastructure bottlenecks, and fragmented policy support. Hydrogen production still depends on expensive electrolysers and clean power availability. CCS requires transport and storage capacity that remains scarce and politically sensitive.

In short, electrons can move faster than molecules.

The economics of momentum

The economics reinforce this trend. Electrified heat is capital-intensive but relatively simple to finance once policy provides a predictable premium. The auction’s pay-per-ton model mimics the logic of the U.S. 45Q tax credit for carbon capture, reward verified abatement, de-risks investment, and lets the market find the most efficient projects.

Hydrogen and CCS, meanwhile, remain hostage to system-level costs. Producing, transporting, and storing molecules, whether hydrogen or CO2, demands massive, integrated infrastructure that no single project can justify alone. Without a guaranteed offtake market or a predictable price for avoided carbon, private investors stay cautious.

That difference in scalability may define the next decade of European decarbonization. Electrification can move incrementally, one boiler, one line, one plant at a time. Molecule-based systems need a whole ecosystem to move together.

Europe’s strategic rebalancing

The timing of this policy pivot is not accidental. High gas prices, volatile ETS costs, and tightening climate targets have forced policymakers to confront industrial exposure to fossil fuel volatility. By electrifying heat with locally sourced renewables, Europe strengthens both energy security and industrial competitiveness.

There is also a deeper strategic message. The electrification auction is a prototype for what the Commission calls the Industrial Decarbonisation Bank, a permanent facility to finance low-carbon industrial investment. If the pilot succeeds, it could expand into a much larger platform, channeling billions into technologies that reduce industrial CO2 at source.

In that sense, this is more than a funding call, it is a stress test for Europe’s ability to move from rhetoric to replication.

The coming divergence, electrons vs. molecules

This growing divergence between electron-based and molecule-based approaches reflects a broader philosophical split in Europe’s transition planning.

Hydrogen and CCS have long dominated headlines, political speeches, and national strategies. They are indispensable for deep decarbonization, no one doubts that, but their deployment remains slow, costly, and infrastructure-heavy. Electrification, on the other hand, advances quietly because it relies on existing systems.

In practice, a factory can replace a fossil boiler with an electric one far faster than it can install a CCS unit or switch to hydrogen combustion. The capital costs may be comparable, but the regulatory and infrastructure complexity is not. That simplicity could make electrification Europe’s bridge technology for the 2030s, cutting emissions now, while hydrogen and CCS catch up.

The danger, of course, is overcorrection. A Europe that bets everything on electrification could still hit limits, grid capacity, renewable intermittency, and high industrial electricity prices. The challenge will be to use auctions like this not as an endpoint, but as a learning mechanism to optimize system integration, combining the immediacy of electrification with the longer-term flexibility of low-carbon molecules.

A quiet revolution in industrial policy

For decades, industrial decarbonization was seen as a future problem. The Innovation Fund’s electrification auction brings it into the present tense. It rewards results, not roadmaps, and signals that Brussels is finally willing to spend serious money on proven solutions.

It also marks a new chapter in industrial policy, Europe is starting to back winners based on technological readiness, not political symmetry. Where hydrogen and CCS still depend on frameworks under construction, electrification now has a launchpad.

Whether this becomes a model for future auctions covering cooling, storage, or low-carbon feedstocks will depend on its success in attracting viable bids and delivering measurable CO2 reductions. But the direction of travel is clear, Europe wants to move from blueprints to building sites.

The transition’s next inflection point

In the end, the auction’s real importance lies in its symbolism. For years, Europe has talked about industrial decarbonization as a long-term challenge. This initiative says something different, the technologies are ready, the money is available, and the political case is undeniable.

Electrons may not solve everything, but they are solving something now. Molecules will follow, eventually. The race is no longer between technologies, but between time and temperature.

Europe’s first industrial electrification auction may not make headlines like hydrogen valleys or CCS hubs, but in terms of tangible progress, it might just prove the most consequential.

By Leon Stille for Oilprice.com

Carbon Tax Puts EU at Odds With Export Majors

- The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is a new EU tax on imports from countries with less strict emission standards, designed to create a "level playing field" for European industries hurt by the EU's strict green mandates.

- Major exporters like India are already seeking alternative markets for goods such as steel, the production of which is incompatible with the EU’s low-emission requirements.

- The effectiveness of CBAM is at risk due to issues in its implementation, specifically inconsistencies in the default emission values assigned to exporting nations, which some industry executives warn could allow high-emission imports to enter the EU with insufficient carbon costs.

On January 1 next year, a new tax will come into effect in the European Union. Dubbed the carbon border adjustment mechanism, the tax will be imposed on imports from non-EU countries with less strict emission reduction standards. Those countries are already speaking out against the tax—and the EU is about to face some unforeseen consequences.

Last week, Reuters reported that Indian steel exporters were looking for new markets to replace the European Union, which currently absorbs as much as two-thirds of Indian steel exports. India’s steel manufacturing is done in blast furnaces fueled with coal, which is incompatible with the European Union’s emission reduction plans. Steel mills could switch to electric arc furnaces from coal-fired blast furnaces. The electric version has a lower emissions footprint, but such a switch would take time and money—quite a bit of it. Europe itself makes steel in electric arc furnaces, and this is still rather expensive.

It was in response to European industries that the carbon border adjustment mechanism, or CBAM, was drafted in the first place. The EU’s strict emission reduction targets and the mandatory requirements that go with them were making European goods uncompetitive on international markets, hurting steelmakers, cement producers, carmakers, and all other industries, really. So, these industries spoke up and got this sort of a concession, which fits in perfectly with the European Union’s ambition to become a standard-setter in climate policies.

“If you want to create a level playing field, if you are asking this [green standards] from companies in Europe, then it also makes sense to ask it from companies from outside of Europe [which are selling into the EU],” the EU’s climate commissioner, Wopke Hoekstra, told the Financial Times this month. Indeed, it makes sense to have one standard for all. Unfortunately, enforcement may not be as easy as Mr. Hoekstra made it sound in his interview with the Financial Times.

“As people get used to it and it gets implemented, it will be less of a conversation,” Hoekstra claimed. That might be true for people in general, but for people running companies that depend on export revenues, things look a little bit differently. To comply with European standards in emission reduction, these specific people would need to spend a certain amount of money to transform their production process and make it more vulnerable to cost shocks because electric arc furnaces, as the name suggests, work with electricity rather than coal. This is arguably a big reason why European steelmakers are finding it difficult to compete: for each ton of carbon dioxide they emit, European industries have to pay some 80 euro, equal to over $93. Yet they do not really have a choice.

India, China, and other exporters to the European Union do have a choice. “Some of those making money out of [fossil fuels] are seeking to prolong that process. We have seen this quite explicitly,” Wopke Hoekstra told the FT. “Some of the petrostates are seeking to at least slow down rather than speed up [the energy transition].” Indeed, most countries that make good money out of export commodities that enjoy strong and stable demand have very little motivation to kill their cash cows, as it were, just to please the policymakers in Brussels. It appears that Brussels is aware of it—and of the fact that the European Union is heavily dependent on imports of essential goods.

Politico reported this month that while the CBAM was more or less done in terms of text, it still needed work in the emission measurement part. It was unclear as of yet how exactly the specific emissions of exporters to the EU from India, China, Saudi Arabia, and others “making money out of fossil fuels” were going to be measured. The publication said it had seen two documents on the emission measurement, one containing emission benchmarks and the other default value for the production of the goods that would be subject to the new tax from January. It also said there were signs of the EU circumventing its own rules to keep the imports flowing in.

Politico cited industrial executives as saying the default values for emissions for certain countries that export to the EU were set too low to be real, including some steel production in China that, according to these estimates, turned out to be lower-emission than steel production in the EU.

“Inconsistencies in the figures of default values and benchmarks would dilute the incentive for cleaner production processes and allow high-emission imports to enter the EU market with insufficient carbon costs,” an industry representative told Politico. “This could result in a CBAM that is not only significantly less effective but most likely counterproductive.”

One could, in fact, argue that the CBAM is counterproductive by definition because it seeks to make more products expensive for more people in pursuit of an elusive goal of arresting changes in global temperatures. Yet the EU is going ahead with it, although it will provide “additional flexibilities” in response to the United States’ unfavorable reaction to the new levy.

By Irina Slav for Oilprice.com

Labor Shortages Threaten to Derail Europe's Energy Security Pivot

- The EU's goal to completely phase out Russian natural gas imports by 2027 is facing a major challenge due to a growing shortage of skilled labor needed to build the necessary alternative infrastructure.

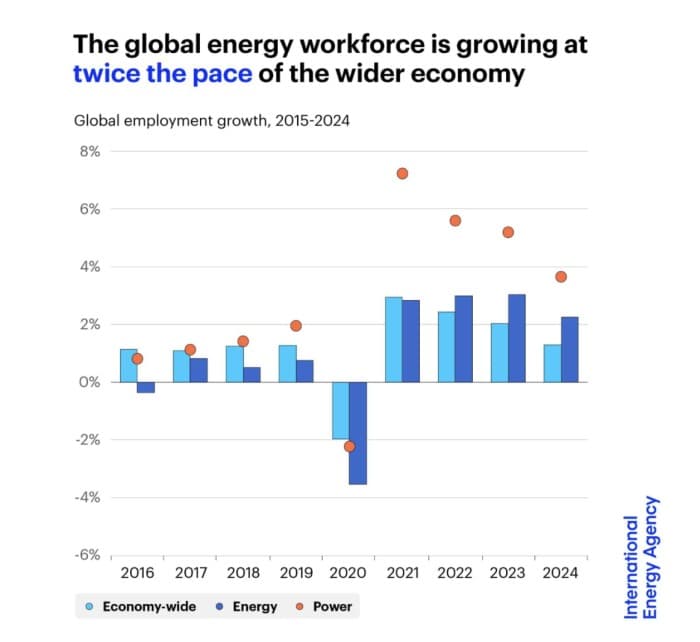

- The global energy sector is booming, with jobs up by over 5 million since 2019, but a survey of 700 companies found that more than half reported critical hiring bottlenecks for electricians, engineers, and grid technicians.

- In addition to the workforce crisis, the IEA also warns that current electricity market designs are failing to send the right long-term investment signals and must be redesigned to value flexibility for a system dominated by renewables.

The European Union has drawn a line in the sand. By 2027, the bloc intends to phase out Russian natural gas imports completely.

But as the policy ink dries in Brussels, a new challenge is emerging in the real economy…

We might not have enough hands to build the infrastructure that replaces it.

International Energy Agency (IEA) Executive Director Fatih Birol stood alongside European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen last week and called it the "end of an era."

But he also delivered a warning.

The transition away from Russian energy is only as strong as the workforce available to execute it. And right now... that workforce is stretched to the breaking point.

The Golden Rule: Diversification

Following the invasion of Ukraine, the IEA responded with a 10-Point Plan to reduce reliance on Russian fuel. The results have been swift. Europe has moved toward firmer footing, diversifying suppliers and accelerating renewables.

Dr. Birol, speaking at the European Commission, laid out the new philosophy simply:

“In the energy world, overreliance can quickly turn into major geopolitical vulnerabilities. My number one golden rule for energy security is diversification.”

The deal is done. The timeline is set. But policy is just paper until it is built.

A Boom with a Bottleneck

The energy sector is growing. Fast.

According to the IEA’s newly released World Energy Employment 2025 report, the sector is a job-creation machine.

Global energy employment hit 76 million people in 2024. It is up by more than 5 million since 2019. Last year alone, energy jobs grew by 2.2%, a rate growing at twice the pace of the wider global economy.

The center of gravity is shifting, too.

- The power sector has overtaken fuel supply as the industry's top employer.

- Solar PV is the primary driver of growth.

- Jobs in EV manufacturing and battery production surged by nearly 800,000.

At first glance, all seems well, but the report highlights a deepening shortage of skilled labor. Of the 700 energy-related companies surveyed, more than half reported critical hiring bottlenecks.

Europe is facing a paradox. It has the capital. It has the policy mandates. But it lacks the electricians, the engineers, and the grid technicians to deploy them on schedule.

These shortages threaten to slow the building of infrastructure, delay projects, and raise system costs exactly when Europe needs to move fastest.

Rewiring the Market's Operating System

As the grid transforms to accommodate wind, solar, and batteries, the market design—the economic logic that governs the grid—is struggling to keep up.

The IEA’s concurrent report, Electricity Market Design, finds a disconnect.

Short-term markets are working well; they are efficiently dispatching power hour-by-hour. But long-term markets? They are failing to send the right investment signals.

The old models weren't built for a system dominated by renewables. The report argues that we need to redesign these markets to value flexibility and attract long-term capital.

If we don't fix the market signals, the investment won't flow... no matter what the policymakers in Brussels say.

The Global Context

The pivot isn't happening in a vacuum. While Europe finalizes its divorce from Russian gas, the rest of the world is moving, too.

- In Norway: Dr. Birol met with Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre to discuss Norway's role as a guarantor of energy security and a partner in clean cooking initiatives for Africa.

- In Southeast Asia: 150 policymakers gathered in Vietnam for the IEA’s 22nd Energy Efficiency Policy Training Week, addressing rapidly growing demand in the region.

The Bottom Line

The 2027 phase-out deal is a massive geopolitical win for Europe. It signals resilience. But the hard work is just starting.

We have traded a geopolitical crisis for an industrial one. The race is no longer just about securing gas contracts; it is about securing the talent and the market structures to keep the lights on.

Europe has cut the cord. Now, it has to build the battery.

By Michael Kern for Oilprice.com

No comments:

Post a Comment