An ancient story of investors trying to recover billions of dollars of debt Russia defaulted on after the last Tsar was overthrown in the October Revolution has come up again.

Russia has called on US-based Noble Capital to withdraw a $225.8bn lawsuit over Tsarist-era bonds by January 30 or face a motion to dismiss the case under the US Foreign State Immunities Act, international law firm Marks & Sokolov told state news agency RIA Novosti on January 16.

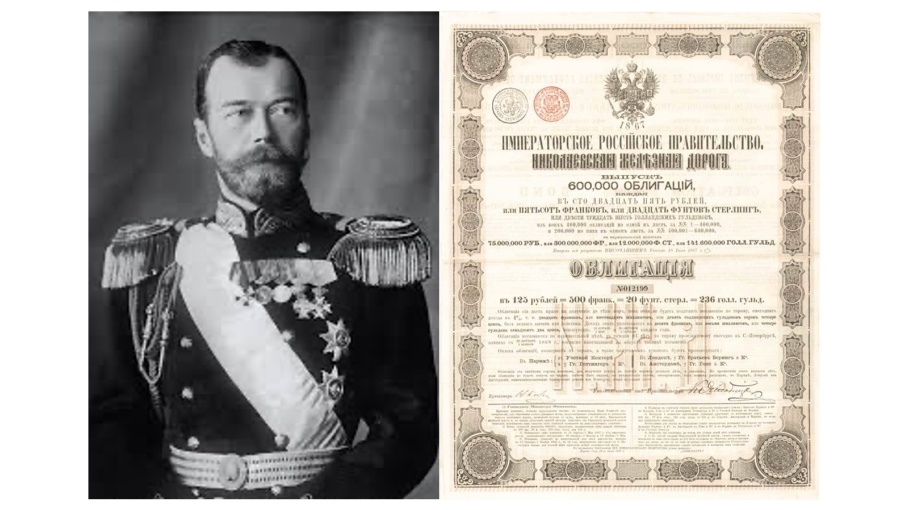

At the last fin de siècle of the millennium Tsar Nicholas II had borrowed billions from the international capital markets, largely based in Paris in those days, to fund Russia’s economy. Pre-revolution Russia was a military and agricultural powerhouse with easy access to the capital markets. However, Lenin’s revolution threw Russia into chaos and the new Soviet government defaulted on the debt. For more than 100 years, investors, and their descendants, have been trying to recover their money ever since.

In the latest attempt, a legal challenge, filed in June 2025 in the US District Court for the District of Columbia, targets the Russian Federation, the Russian Ministry of Finance, the Bank of Russia and the National Welfare Fund. Noble Capital claims it is the legal successor and rightful owner of bonds issued by the Russian Empire more than a century ago to American investors.

According to the lawsuit, “the Russian Federation, in violation of the doctrine of state continuity, has refused and continues to refuse to fulfil certain sovereign debt obligations” inherited from its predecessor states. The fund is also seeking court approval to satisfy these alleged obligations using Russian state assets currently frozen in the US.

Moscow, through its legal representation, has rejected any liability for debts issued prior to the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. “Neither the USSR nor the Russian Federation ever acknowledged their responsibility for them under established international law. They were long ago consigned to the 'trash can of history,’” Marks & Sokolov said in its statement.

In the last three decades several Western countries, including France and the UK, have reached partial settlements with Russia over similar claims in the 1990s. The US has never concluded a bilateral agreement with Moscow concerning compensation for American holders of Imperial Russian debt.

Noble Capital has not publicly responded to Russia’s withdrawal request, Vedomosti reported. The most recent activity in the court case took place in November 2025, according to filings.

Tsar’s bonds

The bonds at the centre of Noble Capital’s lawsuit originate from sovereign debt instruments issued by the Russian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, prior to the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. These securities were sold widely on international markets, particularly in France, the UK, Germany, and the US, to finance the Tsarist regime's ambitious infrastructure projects, military expenditures, and industrialisation efforts, under the Protr Stylopin reformist government.

One of the most significant waves of issuance occurred under Tsar Nicholas II, especially in the early 1900s, as the Russian government sought to modernise the empire and strengthen its strategic position. Foreign investors were attracted by high yields and the implicit backing of one of the world's largest territorial powers at the time.

French investors were by far the largest holders, with an estimated 1.6mn French citizens having purchased Russian bonds. These were often marketed as “safe, state-backed” instruments – the triple A bonds of their day – and sold to small retail investors through banks and brokers as a solid long-term investment to feather an old age. The French government actively promoted the bonds as part of its diplomatic alignment with Russia, which culminated in the Franco-Russian Alliance at the turn of the century.

In the US, similar instruments were issued and marketed to private investors, although on a smaller scale. The bonds were typically denominated in gold or in foreign currencies and were issued under various terms, including railway bonds, government loans, and municipal debt backed by the Imperial government.

Following the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917, Lenin’s Soviet government issued a decree repudiating all Tsarist debts. This marked the first time in modern history that a major state defaulted outright on its sovereign obligations – a trick that Russia nearly repeated in the 1998 financial meltdown. The Soviet leadership argued that the debt was illegitimate and had served to enrich capitalist powers and suppress the Russian working class. Ukraine has made similar “odious debt” arguments to refuse to repay a $3bn bond issued to the Yanukovych administration by Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2013 that helped spark the EuroMaidan revolution that ousted him.

Despite the Revolutionary default, the bonds continued to trade on secondary markets for decades, often at steep discounts. Some were acquired by speculators and legal entities, who viewed them as potential claims should a future Russian government resume payments. While some settlements were later reached—such as the 1996 Franco-Russian agreement to compensate French holders—no agreement was ever achieved with US investors.

1990s attempt to retire the debt

The bonds were a millstone for the Yeltsin administration in the 1990s, spoiling Russia’s credit profile at a time when it had to borrow billions from the likes of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as it struggled to recover from the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the newly formed Russian Federation faced renewed pressure from foreign bondholders to settle outstanding claims on Imperial Russian debt, as a way of breaking European Russia’s links with its Soviet misadventure. Among the most serious diplomatic efforts to deal with the debt came during the premiership of Viktor Chernomyrdin, who served as Prime Minister from 1992 to 1998 under President Boris Yeltsin.

Chernomyrdin’s government, tasked with stabilising Russia’s post-Soviet economy and re-establishing international creditworthiness, re-engaged for the first time since the revolution in a series of top level negotiations with Western governments over the legacy debts of both the Soviet Union and the Russian Empire. These talks were part of broader efforts to normalise Russia’s financial relationships and secure access to international capital markets on which Russia’s economy had become increasingly dependent.

And some progress was made. Russia reached partial settlements with several countries regarding Imperial-era bonds. The most notable agreement was with France. In 1996, after prolonged negotiations, Moscow and Paris signed a bilateral accord under which Russia agreed to pay FRF400mn (around $80mn at the time) to compensate the descendants of approximately 300,000 French holders of Tsarist bonds. The settlement was framed not as full repayment, but as a goodwill gesture to close the issue diplomatically. The French government had purchased the bonds from its citizens and thus held the claims directly.

However, similar agreements with other creditor nations, including the US, were never concluded. One of the obstacles was that, unlike France or the UK, the US government had not formally acquired the claims of its bondholders, making it more difficult to conduct a state-to-state resolution. In addition, the scale of the claims and the lack of detailed registries of US bondholders complicated negotiations.

In a 1997 interview with The New York Times, Russian officials made clear that Moscow considered the 1918 repudiation of Tsarist debts as final, but remained open to limited settlements in the interest of diplomatic normalisation. Chernomyrdin, known for his pragmatic approach and unintelligible speeches, sought to distance modern Russia from the legal and financial burdens of both the Soviet and Imperial eras, but recognised that resolving legacy debt issues was essential to improving Russia’s global financial standing.

Ultimately, the 1990s efforts under Chernomyrdin led to some targeted settlements, but failed to produce a comprehensive resolution for US holders of Tsarist bonds—a legacy that continues to fuel legal claims to this day.

As Chernomyrdin most famously said: “We hoped for the best, but everything turned out like always.”

No comments:

Post a Comment