MONOPOLY CAPITALI$M

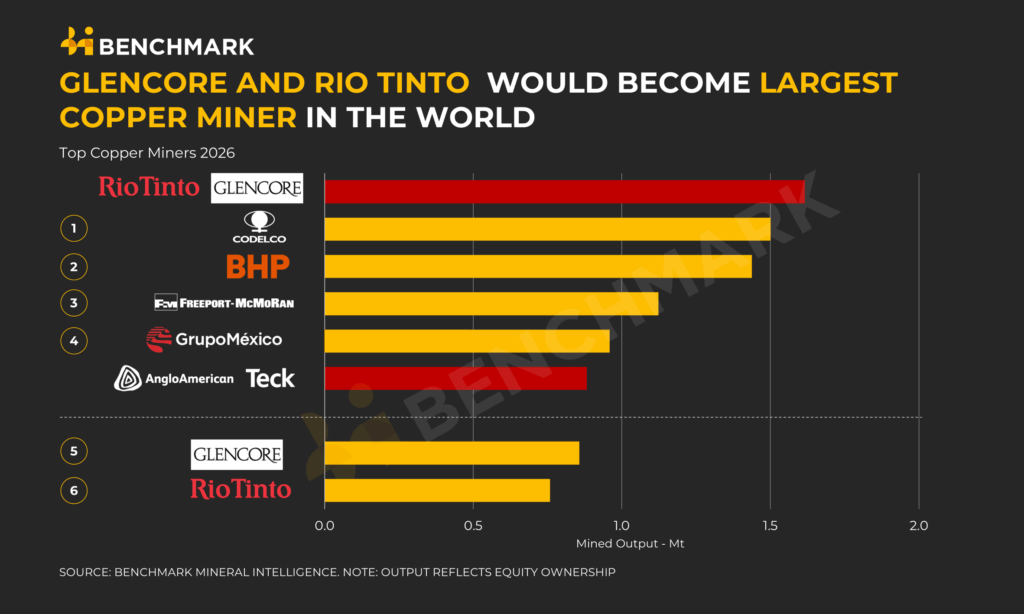

Rio Tinto-Glencore merger may need asset sales to win over China

The proposed tie-up between Rio Tinto and Glencore could require asset sales to secure regulatory approval from top commodity buyer China, which has longstanding concerns about resource security and market concentration.

The two mining giants revealed last week that for the second time in two years they were in early merger talks – potentially creating the world’s largest mining company with a market value of more than $200 billion.

But analysts and lawyers said the scale of their sales to China means any deal will need approval from Beijing, as have past mining mega-deals such as Glencore’s $35 billion purchase of Xstrata in 2013.

China’s antitrust regulator is likely to be concerned about a combined entity’s concentration in copper production and marketing as well as iron ore marketing, several analysts and lawyers told Reuters. Beijing may also see an opportunity to force asset sales to friendly entities, they added.

Even before the Glencore talks were made public, Rio Tinto had already been exploring an asset-for-equity swap aimed at trimming the 11% holding of its biggest shareholder, state-run Aluminium Corporation of China, known as Chinalco. Rio Tinto’s Simandou iron ore mine in Guinea and Oyu Tolgoi copper mine in Mongolia were among the assets of interest to Chinalco, sources said then.

To get the Glencore deal over the line, assets in Africa are especially likely sales candidates as Latin America has become less accepting of Chinese investment, according to Glyn Lawcock, an analyst at Barrenjoey in Sydney.

“China will see this as an opportunity to squeeze out assets,” he said.

China’s commerce ministry, its market regulator and Chinalco did not respond to questions about the deal. Glencore and Rio Tinto declined to comment.

Glencore precedent

Glencore has been here before. In 2013, Chinese regulators forced the Swiss-based company to sell its stake in the Las Bambas copper mine in Peru, one of the world’s largest, to Chinese investors for nearly $6 billion in exchange for blessing its takeover of Xstrata.

“The Las Bambas deal is still looked at as a very successful solution and it’s going to be a potential playbook that regulators can draw on,” a China-based partner at an international law firm said on condition of anonymity.

Glencore also agreed to sell Chinese customers minimum quantities of copper concentrate at certain prices for just over seven years as Beijing was concerned the merged group would have too much power over the copper market.

Rio Tinto, Glencore mull ASX coal spin-off

Rio Tinto (RIO) and Glencore (GLEN) are said to be examining whether a coal-heavy business could be spun off into an ASX-listed vehicle as part of early-stage talks on a potential merger that would create the world’s largest mining company.

The companies confirmed last week they are discussing a possible combination of some or all of their businesses, sparking speculation about how assets that sit awkwardly together would be handled, particularly coal and Glencore’s lucrative trading arm.

“All we know is that they are trying to hammer out important details, like the price, the premium, who would run the new company, exactly what structure it would have,” Clara Ferreira Marques, Bloomberg’s Asia-Pacific head of commodities, said on the The Australia Podcast on Thursday.

“They’re hiring banking teams to help them do that, and they really have to come up with some sort of proposal by the fifth of February to meet the UK takeover panel rules.”

One option under consideration is carving out coal assets, potentially into a separately listed Australian vehicle, echoing BHP’s (ASX, LON: BHP) South32 demerger a decade ago.

Glencore’s coal operations across NSW, Queensland, central Africa and Latin America would account for about 8% of a combined group’s $45.6 billion in EBITDA and could be worth tens of billions of dollars. Glencore’s trading arm, which would represent about 9% of earnings, remains another sensitive piece of the puzzle.

Analysts have also floated alternatives, including Glencore spinning off coal ahead of any transaction or Rio bidding only for Glencore’s copper assets, following Glencore’s decision last year to abandon a self-driven coal separation.

Why now

The renewed talks come as pressures that were present a year ago have intensified, particularly around copper, scale and market positioning.

“What has changed since the last time they held talks is that some of the issues that were already there a year ago have become a lot more stark,” Ferreira Marques said. “You look at the copper price, we’re now over $13,000 a tonne. That makes the case for adding copper to your portfolio not only compelling, but urgent.”

She added that Rio’s recent share price performance has improved the financial logic of a deal, while the sector’s shrinking relative size has become harder to ignore.

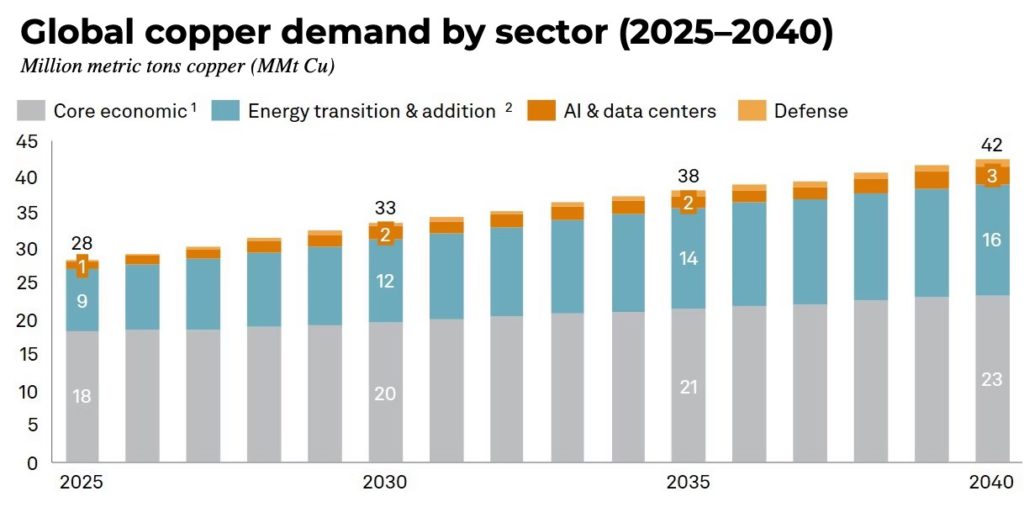

Demand for the metal is anticipated to rise by as much as 50% by 2040, according to S&P Global Energy & Market Intelligence, leading to a projected production deficit of up to 10 million tonnes annually by that time.

A Rio Tinto-Glencore tie-up would position the new company as the leading copper producer globally, accounting for approximately 7% of the world’s output.

“You look at Rio Tinto at about $141 billion, and then you look at Nvidia at $4.5 trillion,” she said. “The problem of scale is very important. It’s not just about being the biggest, it’s about being able to attract generalist investors, talent and opportunities.”

Leadership changes have also helped reset the dynamic. Rio now has a new chief executive in Simon Trott and a more deal-minded chair in Dominic Barton, while Glencore is led by Gary Nagle, who has called the tie-up the “most obvious” deal in mining.

Previous talks in late 2024 stalled over valuation, culture and control, but people familiar with the discussions say both sides now appear more open to compromise.

Hurdles ahead

Price remains the primary obstacle, followed closely by cultural fit, coal exposure and regulatory risk. Rio exited thermal coal in 2018, and some investors remain constrained by mandates that bar coal holdings, even as the political climate in the US has softened and coal profitability has endured longer than expected.

Antitrust scrutiny would be significant, particularly given China’s role as a major stakeholder in Rio, and the operational risks tied to Glencore’s copper assets in jurisdictions such as the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Speculation that BHP could attempt to disrupt the talks with a rival bid for Glencore has so far been played down.

“At this point, it’s unlikely,” Ferreira Marques said. “BHP is not a company that jumps on things at the last minute. The signalling is very much that they wouldn’t step in.”

She cautioned, however, that early-stage deals can still unravel. “When companies talk about an M&A deal, they basically tell the world that they need to do something,” she said, adding that BHP’s earlier bid for Anglo American (LON: AAL) helped reopen the door to mega-deals across the sector.

Whether the talks culminate in a full merger that gives rise to a GlenTinto, a RioCore or something else entirely, a partial asset deal or yet another false start, the discussions underscore how urgently the world’s biggest miners are hunting for growth in an increasingly copper-constrained world.

Copper assets are in even higher demand today given the metal’s role in the green transition and artificial intelligence. Rio Tinto and Glencore are shifting their focus to the metal, as are rival miners including Australia’s BHP.

Chinese regulators will also be examining a planned $53 billion copper-focused merger between Anglo American and Teck Resources, Teck CEO Jonathan Price said in September.

Political challenges

Copper’s rising importance is politicizing the metal. The White House has alluded to China’s dominance over the supply chain as a direct threat to national security, and it remains to be seen how it would react to major mineral asset sales to Chinese interests.

A combined Rio Tinto-Glencore would market about 17% of global copper supply, according to Lawcock, although analysts at Barclays say the share of mine production is only 7.5% and unlikely to trigger major antitrust concerns.

Nonetheless politics has doomed deals before.

US chipmaker Qualcomm walked away from a $44 billion deal to buy NXP Semiconductors in 2018 after failing to get approval from Chinese regulators in what was seen as a response to the trade war then underway between Washington and Beijing. The inability to get Chinese regulators on board similarly sank Nvidia’s proposed takeover of Arm Ltd.

In previous resource deals, however, Beijing has given approval as part of a bargain. A year before the sale of Las Bambas, Beijing required major changes to a tie-up between Japan’s Marubeni and US grain merchant Gavilon, citing food security concerns.

“Clearly this would be a long, complicated deal from a regulatory approval perspective,” Mark Kelly, CEO of advisory firm MKI Global Partners, wrote in a note, “and the presence of Chinalco on Rio’s shareholder register always complicates this picture further.”

(By Lewis Jackson, Amy Lv, Melanie Burton, Anousha Sakoui and Clara Denina; Editing by Veronica Brown, Tony Munroe and Jamie Freed)

No comments:

Post a Comment