The Conversation

April 4, 2024

Mayan ruins (Shutterstock)

We live in a light-polluted world, where streetlamps, electronic ads and even backyard lighting block out all but the brightest celestial objects in the night sky. But travel to an officially protected “Dark Sky” area, gaze skyward and be amazed.

This is the view of the heavens people had for millennia. Pre-modern societies watched the sky and created cosmographies, maps of the skies that provided information for calendars and agricultural cycles. They also created cosmologies, which, in the original use of the word, were religious beliefs to explain the universe. The gods and the heavens were inseparable.

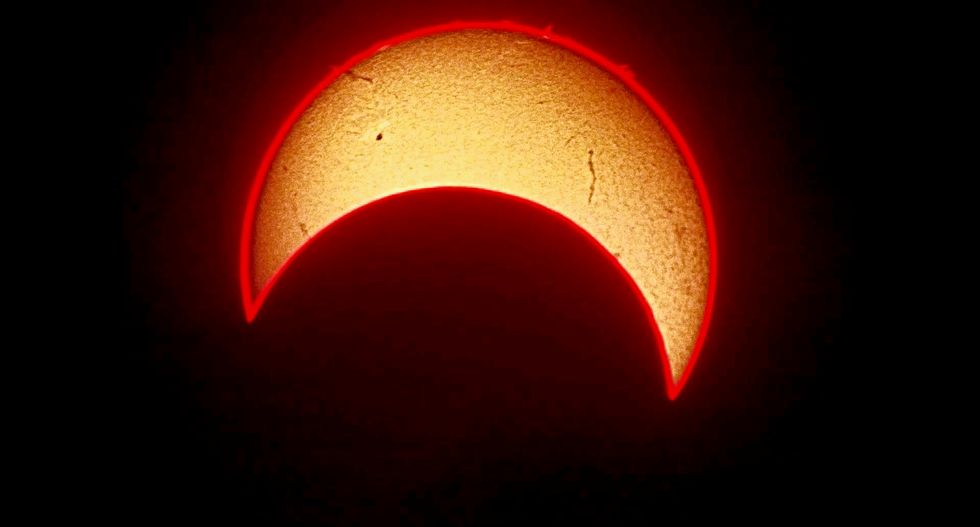

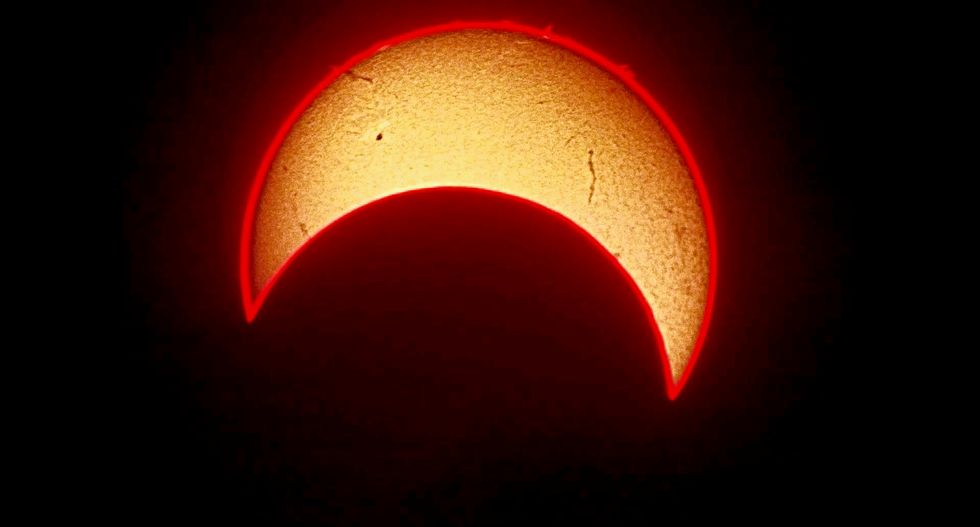

The skies are orderly and cyclical in nature, so watch and record long enough and you will determine their rhythms. Many societies were able to accurately predict lunar eclipses, and some could also predict solar eclipses – like the one that will occur over North America on April 8, 2024.

The path of totality, where the Moon will entirely block the Sun, will cross into Mexico on the Pacific coast before entering the United States in Texas, where I teach the history of technology and science, and will be seen as a partial eclipse across the lands of the ancient Maya. This follows the October 2023 annular eclipse, when it was possible to observe the “ring of fire” around the Sun from many ancient Maya ruins and parts of Texas.

A millennia ago, two such solar eclipses over the same area within six months would have seen Maya astronomers, priests and rulers leap into a frenzy of activity. I have seen a similar frenzy – albeit for different reasons – here in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, where we will be in the path of totality. During this period between the two eclipses, I have felt privileged to share my interest in the history of astronomy with students and the community.

Ancient astronomers

The ancient Maya were arguably one of the greatest sky-watching societies. Accomplished mathematicians, they recorded systematic observations on the motion of the Sun, planets and stars.

From these observations, they created a complex calendar system to regulate their world – one of the most accurate of pre-modern times.

Astronomers closely observed the Sun and aligned monumental structures, such as pyramids, to track solstices and equinoxes. They also utilized these structures, as well as caves and wells, to mark the zenith days – the two times a year in the tropics where the Sun is directly overhead and vertical objects cast no shadow.

Maya “Underworld” Observatory Revealed | National Geographic.

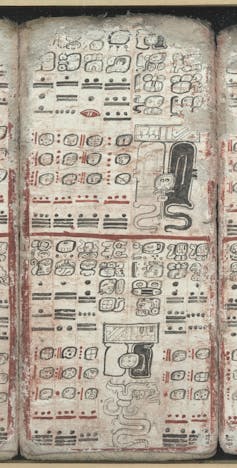

Maya scribes kept accounts of the astronomical observations in codices, hieroglyphic folding books made from fig bark paper. The Dresden Codex, one of the four remaining ancient Maya texts, dates to the 11th century. Its pages contain a wealth of astronomical knowledge and religious interpretations and provide evidence that the Maya could predict solar eclipses.

From the codex’s astronomical tables, researchers know that the Maya tracked the lunar nodes, the two points where the orbit of the Moon intersects with the ecliptic – the plane of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, which from our point of view is the path of the Sun through our sky. They also created tables divided into the 177-day solar eclipse seasons, marking days where eclipses were possible.

Heavenly battle

But why invest so much in tracking the skies?

Knowledge is power. If you kept accounts of what happened at the time of certain celestial events, you could be forewarned and take proper precautions when cycles repeated themselves. Priests and rulers would know how to act, which rituals to perform and which sacrifices to make to the gods to guarantee that the cycles of destruction, rebirth and renewal continued.

Eclipse panels in the Dresden Codex.

Saxon State University and Library - Dresden

In the Maya’s belief system, sunsets were associated with death and decay. Every evening the sun god, Kinich Ahau, made the perilous journey through Xibalba, the Maya underworld, to be born anew at sunrise. Solar eclipses were seen as a “broken sun” – a sign of possible cataclysmic destruction.

Kinich Ahau was associated with prosperity and good order. His brother Chak Ek – the morning star, which we now know as the planet Venus – was associated with war and discord. They had an adversarial relationship, fighting for supremacy.

Their battle could be witnessed in the heavens. During solar eclipses, planets, stars and sometimes comets can be seen during totality. If positioned properly, Venus will shine brightly near the eclipsed Sun, which the Maya interpreted as Chak Ek on the attack. This is hinted at in the Dresden Codex, where a diving Venus god appears in the solar eclipse tables, and in the coordination of solar eclipses with the Venus cycles in the Madrid Codex, another Maya folding book from the late 15th century.

An illustration from the Dresden Codex shows the Venus god descending from a sky band containing solar and lunar symbols.

In the Maya’s belief system, sunsets were associated with death and decay. Every evening the sun god, Kinich Ahau, made the perilous journey through Xibalba, the Maya underworld, to be born anew at sunrise. Solar eclipses were seen as a “broken sun” – a sign of possible cataclysmic destruction.

Kinich Ahau was associated with prosperity and good order. His brother Chak Ek – the morning star, which we now know as the planet Venus – was associated with war and discord. They had an adversarial relationship, fighting for supremacy.

Their battle could be witnessed in the heavens. During solar eclipses, planets, stars and sometimes comets can be seen during totality. If positioned properly, Venus will shine brightly near the eclipsed Sun, which the Maya interpreted as Chak Ek on the attack. This is hinted at in the Dresden Codex, where a diving Venus god appears in the solar eclipse tables, and in the coordination of solar eclipses with the Venus cycles in the Madrid Codex, another Maya folding book from the late 15th century.

An illustration from the Dresden Codex shows the Venus god descending from a sky band containing solar and lunar symbols.

Saxon State and University Library - Dresden

With Kinich Ahau – the Sun – hidden behind the Moon, the Maya believed he was dying. Renewal rituals were necessary to restore balance and set him back on his proper course.

Nobility, especially the king, would perform bloodletting sacrifices, piercing their bodies and collecting the blood drops to burn as offerings to the sun god. This “blood of kings” was the highest form of sacrifice, meant to strengthen Kinich Ahau. Maya believed the creator gods had given their blood and mixed it with maize dough to create the first humans. In turn, the nobility gave a small portion of their own life force to nourish the gods.

Time stands still

In the lead-up to April’s eclipse, I feel as if I am completing a personal cycle of my own, bringing me back to earlier career paths: first as an aerospace engineer who loved her orbital mechanics classes and enjoyed backyard astronomy; and then as a history doctoral student, studying how Maya culture persisted after the Spanish conquest.

An image of the Maya sun god Kinich Ahau, made between the sixth and ninth centuries, now housed in Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology.

With Kinich Ahau – the Sun – hidden behind the Moon, the Maya believed he was dying. Renewal rituals were necessary to restore balance and set him back on his proper course.

Nobility, especially the king, would perform bloodletting sacrifices, piercing their bodies and collecting the blood drops to burn as offerings to the sun god. This “blood of kings” was the highest form of sacrifice, meant to strengthen Kinich Ahau. Maya believed the creator gods had given their blood and mixed it with maize dough to create the first humans. In turn, the nobility gave a small portion of their own life force to nourish the gods.

Time stands still

In the lead-up to April’s eclipse, I feel as if I am completing a personal cycle of my own, bringing me back to earlier career paths: first as an aerospace engineer who loved her orbital mechanics classes and enjoyed backyard astronomy; and then as a history doctoral student, studying how Maya culture persisted after the Spanish conquest.

An image of the Maya sun god Kinich Ahau, made between the sixth and ninth centuries, now housed in Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology.

DeAgostini/Getty Images

For me, just like the ancient Maya, the total solar eclipse will be a chance to not only look up but also to consider both past and future. Viewing the eclipse is something our ancestors have done since time immemorial and will do far into the future. It is awesome in the original sense of the word: For a few moments it seems as if time both stops, as all eyes turn skyward, and converges, as we take part in the same spectacle as our ancestors and descendants.

And whether you believe in divine messages, battles between Venus and the Sun, or in the beauty of science and the natural world, this event brings people together. It is humbling, and it is also very, very cool.

I just hope that Kinich Ahau will grace us with his presence in a cloudless sky and once again vanquish Venus, which is a morning star on April 8.

Kimberly H. Breuer, Associate Professor of Instruction, University of Texas at Arlington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

For me, just like the ancient Maya, the total solar eclipse will be a chance to not only look up but also to consider both past and future. Viewing the eclipse is something our ancestors have done since time immemorial and will do far into the future. It is awesome in the original sense of the word: For a few moments it seems as if time both stops, as all eyes turn skyward, and converges, as we take part in the same spectacle as our ancestors and descendants.

And whether you believe in divine messages, battles between Venus and the Sun, or in the beauty of science and the natural world, this event brings people together. It is humbling, and it is also very, very cool.

I just hope that Kinich Ahau will grace us with his presence in a cloudless sky and once again vanquish Venus, which is a morning star on April 8.

Kimberly H. Breuer, Associate Professor of Instruction, University of Texas at Arlington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘The ghost has taken the spirit of the Moon’: how Torres Strait Islanders predict eclipses

The Conversation

April 1, 2024

FILE PHOTO: A combination photo shows the lunar eclipse from a blood moon (top L) back to full moon (bottom right) in the sky over Frankfurt, Germany, July 27, 2018. REUTERS/Kai Pfaffenbach/File Photo

It’s eclipse season. The Sun, Earth and Moon are aligned so it’s possible for the Earth and Moon to cast each other into shadow.

A faint lunar eclipse will occur on March 25, visible at dusk from Australia and eastern Asia, at dawn from western Africa and Europe, and for much of the night from the Americas. Two weeks later, on April 8, a total solar eclipse will sweep across North America.

These events are a good time to think about an infamous incident 520 years ago, in which an eclipse prediction was supposedly used to exploit an Indigenous population. The incident has shaped how we think about astronomy and Indigenous cultures – but the real story is far more complex.

Columbus and the eclipse

In June 1503, on his fourth voyage to the Americas, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus and his crew became stranded on Jamaica. They were saved by the Indigenous Taíno people, who gave them food and provisions.

As months passed, tensions grew. Columbus’s crew threatened mutiny, while the Taíno grew frustrated with providing so much for so little in return. By February, the Taíno had reached their breaking point and stopped providing food.

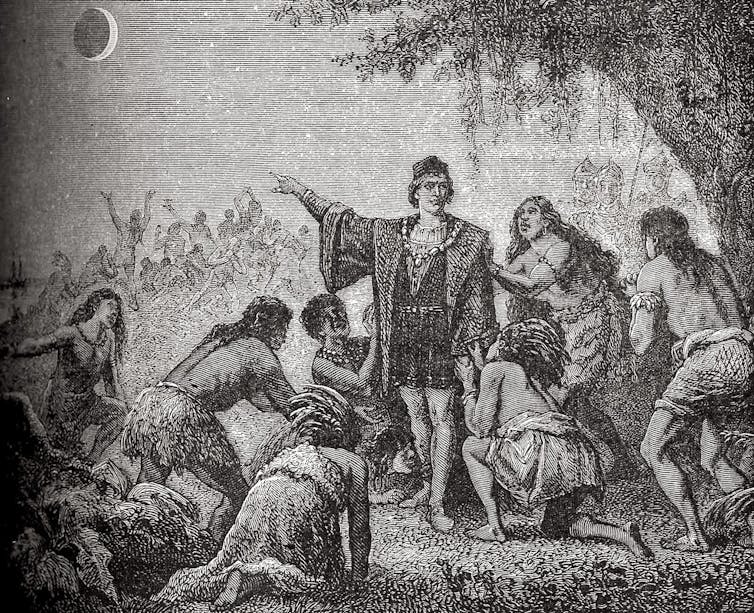

Supposedly, Columbus then consulted an astronomical almanac and discovered a lunar eclipse was forecast for February 29 1504. He took advantage of this knowledge to trick the Taíno, threatening to use his “magic power” to turn the Moon a deep red – “inflamed with wrath” – if they refused to provide supplies.

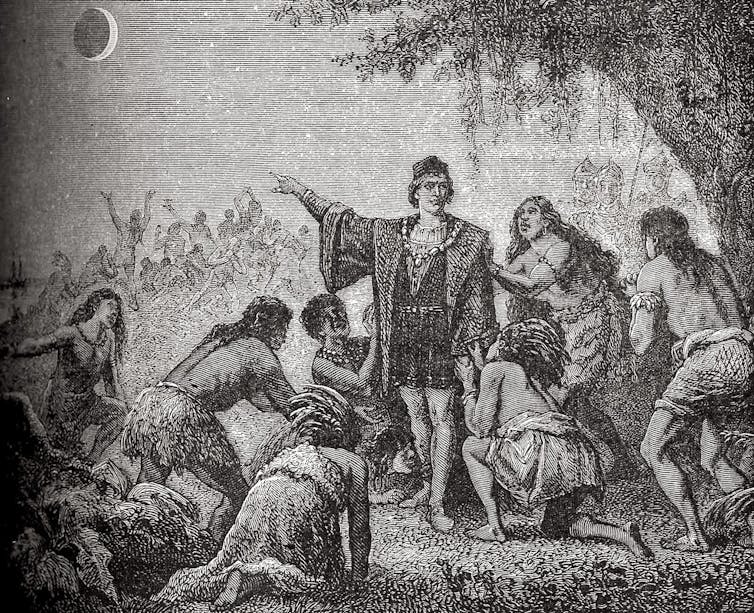

An illustration of Columbus predicting a lunar eclipse to trick the Taíno people into providing his crew with food and supplies. Astronomie Populaire (1879) by Camille Flammarion, via Wikimedia

According to Columbus, this worked and the fearful Taíno continued to supply his crew until relief arrived months later. This incident inspired the idea of the “convenient eclipse”, which has become a familiar trope in works including Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) and The Adventures of Tintin (1949).

But is there truth to the trope? How much did Indigenous peoples really know about eclipses?

Merlpal Maru Pathanu

In the Torres Strait, knowledge of the stars is central to culture and identity. Traditionally, special people were chosen for years of intense instruction in the art of star knowledge, which occurred in a secretive place of higher learning called the kwod. They would be initiated as “Zugubau Mabaig”, a western Islander term meaning “star man” – an astronomer.

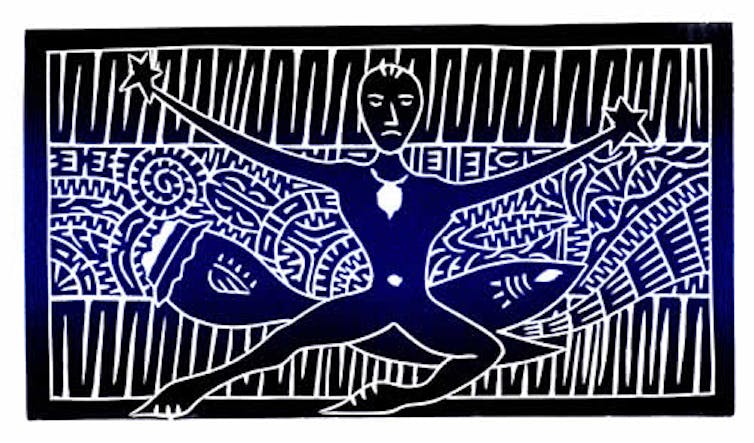

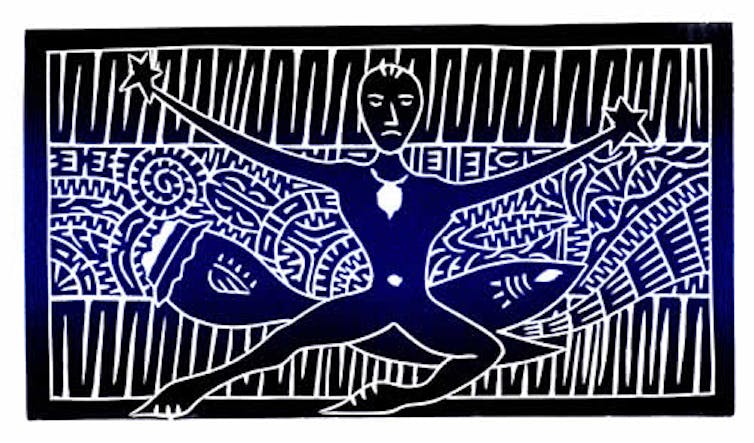

A Zugubau Mabaig, the keeper of constellations in the western Torres Strait, who reads the stars and passes knowledge down through song, dance, and story. David Bosun

Mualgal man David Bosun, a talented artist and son of a Zugubau Mabaig, explains that these individuals paid careful attention to all things celestial. They kept constant watch over the stars to inform their Buai (kinship group) when to plant and harvest gardens, hunt and fish, travel and hold ceremonies.

The final stage of Zugubau Mabaig initiation involved a rare celestial event. Initiates were required to prove their bravery as well as their mental skill by taking the head of an enemy, particularly a sorcerer. In this way they would absorb that person’s powerful magic.

Headhunting raids occurred immediately after a total lunar eclipse, signalled by the blood red appearance of the Moon. During the eclipse, communities performed a ceremony in which dancers donned a special dhari (headdress) as they systematically chanted the names of all the surrounding islands.

An eclipse mask by Sipau Gibuma (Boigu, 1990) and Madthubau Dhibal headdress by Jeff Waia (Saibai, 2008). National Gallery of Australia

The island named when the Moon emerged from the eclipse was the home of the sorcerers they planned to attack. Women and children sought shelter while the men prepared for war. The ceremony, named Merlpal Maru Pathanu (“the ghost has taken the spirit of the Moon”), was planned well in advance by the Zugubau Mabaig.

How was this done?

Predicting an eclipse

The Moon does not orbit Earth in the same plane Earth orbits the Sun. It’s off by a few degrees. The position of the Moon appears to zigzag across the sky over a 29.5-day lunar month. When it crosses the plane connecting Earth and the Sun, and the three bodies are in a straight line, we see an eclipse.

Lunar Analemma, by György Soponyai.

We know that ancient cultures including the Chinese and Babylonians possessed the ability to predict eclipses, and it is rather difficult to do. How did the Zugubau Mabaig accomplish it?

There are some things they would know. First, lunar eclipses only occur during a full moon, and solar eclipses during a new moon.

Second are the “eclipse seasons”: times when the planes of Earth, Moon and the Sun can intersect to form an eclipse. This happens twice a year. Each season lasts around 35 days, and repeats six months later.

Third is the Saros cycle: eclipses repeat every 223 lunar months (approximately 18 years and 11.3 days).

The details are highly complex. But it’s clear that predicting an eclipse requires careful, long-term observations and keeping detailed records, skills Torres Strait Islander astronomers have long possessed.

Flipping the narrative

The Zugubau Mabaig eclipse forecasts turn a common understanding of the history of science on its head. Indigenous peoples did, in fact, develop the ability to predict eclipses.

Perhaps the real situation is better captured in a short story called El Eclipse (1972), by Honduran writer Augusto Monterroso.

In the story, a Spanish priest is captured by Maya in Guatemala, who opt to sacrifice him. He tries to exploit his knowledge that a solar eclipse will occur that day to trick his captors, but the Maya look at the priest with a sense of incredulity. Two hours later, he meets his fate on the altar during the totality of the eclipse.

As the Sun goes dark and the priest’s blood is spilled, a Maya astronomer recites the dates of all the upcoming eclipses, solar and lunar. The Maya had already predicted them.

The truth behind this story is found in the Dresden Codex, a thousand-year-old book of Maya records that includes tables of eclipse predictions.

Learn more at www.aboriginalastronomy.com.au

Duane Hamacher, Associate Professor, The University of Melbourne and David Bosun, Mualgal man, Moa Island, Torres Strait, Indigenous Knowledge

Twitter gears you up for the Great American Eclipse

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Conversation

April 1, 2024

FILE PHOTO: A combination photo shows the lunar eclipse from a blood moon (top L) back to full moon (bottom right) in the sky over Frankfurt, Germany, July 27, 2018. REUTERS/Kai Pfaffenbach/File Photo

It’s eclipse season. The Sun, Earth and Moon are aligned so it’s possible for the Earth and Moon to cast each other into shadow.

A faint lunar eclipse will occur on March 25, visible at dusk from Australia and eastern Asia, at dawn from western Africa and Europe, and for much of the night from the Americas. Two weeks later, on April 8, a total solar eclipse will sweep across North America.

These events are a good time to think about an infamous incident 520 years ago, in which an eclipse prediction was supposedly used to exploit an Indigenous population. The incident has shaped how we think about astronomy and Indigenous cultures – but the real story is far more complex.

Columbus and the eclipse

In June 1503, on his fourth voyage to the Americas, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus and his crew became stranded on Jamaica. They were saved by the Indigenous Taíno people, who gave them food and provisions.

As months passed, tensions grew. Columbus’s crew threatened mutiny, while the Taíno grew frustrated with providing so much for so little in return. By February, the Taíno had reached their breaking point and stopped providing food.

Supposedly, Columbus then consulted an astronomical almanac and discovered a lunar eclipse was forecast for February 29 1504. He took advantage of this knowledge to trick the Taíno, threatening to use his “magic power” to turn the Moon a deep red – “inflamed with wrath” – if they refused to provide supplies.

An illustration of Columbus predicting a lunar eclipse to trick the Taíno people into providing his crew with food and supplies. Astronomie Populaire (1879) by Camille Flammarion, via Wikimedia

According to Columbus, this worked and the fearful Taíno continued to supply his crew until relief arrived months later. This incident inspired the idea of the “convenient eclipse”, which has become a familiar trope in works including Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) and The Adventures of Tintin (1949).

But is there truth to the trope? How much did Indigenous peoples really know about eclipses?

Merlpal Maru Pathanu

In the Torres Strait, knowledge of the stars is central to culture and identity. Traditionally, special people were chosen for years of intense instruction in the art of star knowledge, which occurred in a secretive place of higher learning called the kwod. They would be initiated as “Zugubau Mabaig”, a western Islander term meaning “star man” – an astronomer.

A Zugubau Mabaig, the keeper of constellations in the western Torres Strait, who reads the stars and passes knowledge down through song, dance, and story. David Bosun

Mualgal man David Bosun, a talented artist and son of a Zugubau Mabaig, explains that these individuals paid careful attention to all things celestial. They kept constant watch over the stars to inform their Buai (kinship group) when to plant and harvest gardens, hunt and fish, travel and hold ceremonies.

The final stage of Zugubau Mabaig initiation involved a rare celestial event. Initiates were required to prove their bravery as well as their mental skill by taking the head of an enemy, particularly a sorcerer. In this way they would absorb that person’s powerful magic.

Headhunting raids occurred immediately after a total lunar eclipse, signalled by the blood red appearance of the Moon. During the eclipse, communities performed a ceremony in which dancers donned a special dhari (headdress) as they systematically chanted the names of all the surrounding islands.

An eclipse mask by Sipau Gibuma (Boigu, 1990) and Madthubau Dhibal headdress by Jeff Waia (Saibai, 2008). National Gallery of Australia

The island named when the Moon emerged from the eclipse was the home of the sorcerers they planned to attack. Women and children sought shelter while the men prepared for war. The ceremony, named Merlpal Maru Pathanu (“the ghost has taken the spirit of the Moon”), was planned well in advance by the Zugubau Mabaig.

How was this done?

Predicting an eclipse

The Moon does not orbit Earth in the same plane Earth orbits the Sun. It’s off by a few degrees. The position of the Moon appears to zigzag across the sky over a 29.5-day lunar month. When it crosses the plane connecting Earth and the Sun, and the three bodies are in a straight line, we see an eclipse.

Lunar Analemma, by György Soponyai.

We know that ancient cultures including the Chinese and Babylonians possessed the ability to predict eclipses, and it is rather difficult to do. How did the Zugubau Mabaig accomplish it?

There are some things they would know. First, lunar eclipses only occur during a full moon, and solar eclipses during a new moon.

Second are the “eclipse seasons”: times when the planes of Earth, Moon and the Sun can intersect to form an eclipse. This happens twice a year. Each season lasts around 35 days, and repeats six months later.

Third is the Saros cycle: eclipses repeat every 223 lunar months (approximately 18 years and 11.3 days).

The details are highly complex. But it’s clear that predicting an eclipse requires careful, long-term observations and keeping detailed records, skills Torres Strait Islander astronomers have long possessed.

Flipping the narrative

The Zugubau Mabaig eclipse forecasts turn a common understanding of the history of science on its head. Indigenous peoples did, in fact, develop the ability to predict eclipses.

Perhaps the real situation is better captured in a short story called El Eclipse (1972), by Honduran writer Augusto Monterroso.

In the story, a Spanish priest is captured by Maya in Guatemala, who opt to sacrifice him. He tries to exploit his knowledge that a solar eclipse will occur that day to trick his captors, but the Maya look at the priest with a sense of incredulity. Two hours later, he meets his fate on the altar during the totality of the eclipse.

As the Sun goes dark and the priest’s blood is spilled, a Maya astronomer recites the dates of all the upcoming eclipses, solar and lunar. The Maya had already predicted them.

The truth behind this story is found in the Dresden Codex, a thousand-year-old book of Maya records that includes tables of eclipse predictions.

Learn more at www.aboriginalastronomy.com.au

Duane Hamacher, Associate Professor, The University of Melbourne and David Bosun, Mualgal man, Moa Island, Torres Strait, Indigenous Knowledge

Twitter gears you up for the Great American Eclipse

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment