Toward A More Perfect Union

Exhibition about how the labor movement shaped New York tells a very Jewish story.

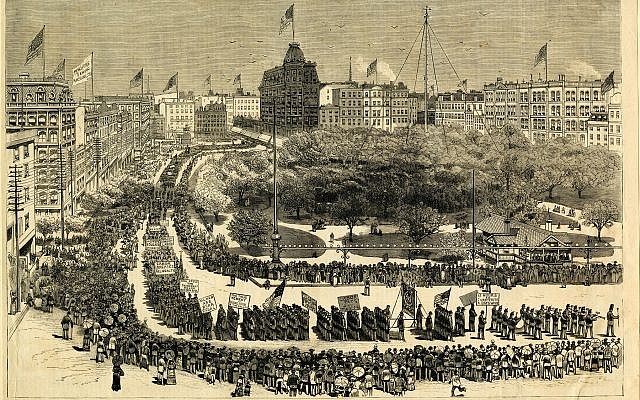

To strike or not to strike: It was Nov. 22, 1909, and that question was at the forefront of the minds of thousands of workers, many of them recent Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, who had gathered that day at the Great Hall of New York’s Cooper Union. For hours, the all-male roster of speakers droned on about poor wages and worse working conditions, while also cautioning against the hardship of actually going on strike.

But a 23-year-old Yiddish-speaking immigrant shirtwaist worker named Clara Lemlich (1888-1982) wasn’t buying it. Shoving her way to the podium, she declared in a fiery voice, “I move that we go on a general strike!

Reacting to the crowd’s roar of approval, Jewish Daily Forward editor Benjamin Feigenbaum asked those present to take a Yiddish oath modeled on a traditional Hebrew pledge: “If I turn traitor to the cause I now pledge, may my hand wither from the arm I now raise.”

Thus began the Uprising of the 20,000, the largest women’s strike in U.S. history, which, despite its name, brought upwards of 40,000 women to the picket line.

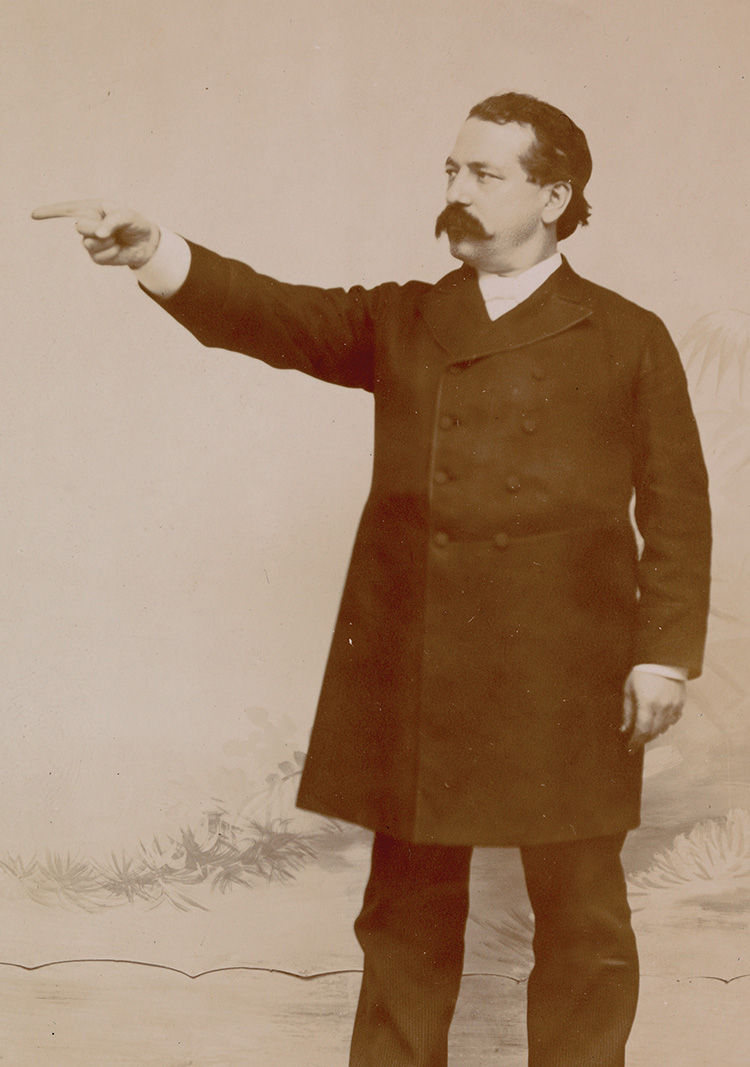

Iconic labor leader Samuel Gompers, circa 1893. Published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper/Courtesy Private Collection

This is only one among many stories chronicled in “City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York,” the newly opened exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York. And many of them are, like this one, intertwined with the history of the Jews of New York.

“The Jewish presence really comes through in the early 20th-century, where you have the rise of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and the Amalgamated Workers Union (AWU),” exhibit curator Steven H. Jaffe told The Jewish Week, adding that “many of the labor leaders were immigrants themselves or the children of immigrants.”

That list begins with Samuel Gompers (1850-1924), who came from a poor Jewish family in London and began working as a cigar maker when he was just 10. He continued that work after moving to the United States with his family and settling on the Lower East Side, where he also quickly became active, first, in the cigar makers’ union and subsequently as a founder of the organization that became known as the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

Workers hand finish garments while managers look on.Courtesy Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives, Cornell University Burton Berinsky

In the 1880s and 1890s, firebrands like Lemlich began arriving from Eastern Europe, where many had already been exposed to socialist ideas and been involved in labor movements there. Eking out a living from piecework or low-paying jobs, this new wave of immigrants constituted “a new Jewish working class that we particularly associate with the garment trades,” said Joshua B. Freeman, professor at Queens College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and editor of the companion book to the exhibit, also titled “City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York.”

Although it was not typical for women at the turn of the 20th century to work outside the home, many Jewish immigrant women were forced to work to help their families make ends meet. Many, says Freeman, “were really girls, 16, 17, 18 years old. … It was a step into independence,” but union involvement also carried the risk of getting arrested or beaten up by strike busters. And Lemlich was not the only Yiddish-speaking Jewish female labor leader. Already, in 1905, six years before the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire killed 146 mostly female and immigrant workers, Rose Schneiderman (1882-1972) had begun publicizing the safety hazards rampant in such buildings. Later in her long career of labor activism, she was named to President Franklin Roosevelt’s National Labor Advisory Board and also served from 1937-1944 as New York State secretary of the State Department of Labor.

ILGWU President David Dubinsky rallies voters along Seventh Avenue for Lyndon Johnson, Robert F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey. Courtesy Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives, Cornell University Burton Berinsky

As for the nature of needle work itself, an interactive video game set alongside a vintage 1910s Singer sewing machine invites you to “Try treading the repurposed machine and guiding the ‘fabric’ with your hand as accurately and as quickly as you can.” The goal is to virtually and accurately “sew” three simulated apron edges. Spread your fingers on either side of the far-from-straight seam pictured on the screen, while also treading the foot pedal below, always making sure the needle and the seam line up perfectly. In real life, you were being watched by the bosses for both your precision and your speed. In this video version, you can read the verdict onscreen. “We couldn’t use a single apron,” mine read. “In 1912, your pay might be 0.4 tenths of a cent for that level of performance. In one 53-hour, 6-day work week, you might earn $1.00 ($25.94 in today’s dollars).”

Freeman points out that while many of the needle workers were Jewish, so were a number of the owners and employers, a situation that made many Jewish leaders uncomfortable. Out of this tension emerged a lasting influence for settling labor disputes: the lasting interest in settling labor disputes and the development of mediation and arbitration procedures. Instrumental to that process was future Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis (1856-1941), who in 1910 helped mediate an end to a strike by 60,000 cloak makers. The agreement was solidified in a document titled the Protocol of Peace — a copy of which is on display here.

Beyond the many historic documents, memorable photos, prints, paintings and news clips on display, the exhibit also offers a number of not-to-be missed artifacts that also carry the story of labor in New York further into the 20th century. One favorite: the over-stuffed Rolodex that belonged to Albert Shanker (1928-1997), the longtime president of the American Federation of Teachers and the United Federation of Teachers. As a sign of Shanker’s political power, the Rolodex is open to the entry for then-Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, including phone numbers in Albany and New York, and handwritten annotations for contacting others in his office. Posters and booklets in Yiddish are also here: a 1908 issue of the Yiddish socialist magazine Zukunftand, and a 1927-1928 calendar booklet from the International Union Bank listing both Jewish and American holidays, among others.

The Jewish presence is only one aspect of the larger story of labor in New York City, and it is shown here side by side with the ways in which workers from every background throughout the city’s history have fought for fair treatment and fair pay. In highlighting the centrality of labor to the city from its founding, and ongoing into the future, the exhibit shows the city in all its social, economic, political and cultural diversity. Understand that history, said Jaffe, and you’ll understand New York City.

“City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York” runs through Jan. 5, 2020, mcny.org.

HAT TIP Arieh Lebowitz

No comments:

Post a Comment