WITH NO HELP FROM ALIENS OR UFO'S OR SUMERIAN GODS

By Matt McGrath Environment correspondent BBC 8 April 2020

UMBERTO LOMBARDO

The forest islands of this part of Bolivia seen from the air

Far from being a pristine wilderness, some regions of the Amazon have been profoundly altered by humans dating back 10,000 years, say researchers.

An international team found that during this period, crops were being cultivated in a remote location in what is now northern Bolivia.

The scientists believe that the humans who lived here were planting squash, cassava and maize.

The inhabitants also created thousands of artificial islands in the forest.

The end of the last ice age, around 12,000 years ago, saw a sustained rise in global temperatures that initiated many changes around the world.

Far from being a pristine wilderness, some regions of the Amazon have been profoundly altered by humans dating back 10,000 years, say researchers.

An international team found that during this period, crops were being cultivated in a remote location in what is now northern Bolivia.

The scientists believe that the humans who lived here were planting squash, cassava and maize.

The inhabitants also created thousands of artificial islands in the forest.

The end of the last ice age, around 12,000 years ago, saw a sustained rise in global temperatures that initiated many changes around the world.

tUMBERTO LOMBARDO

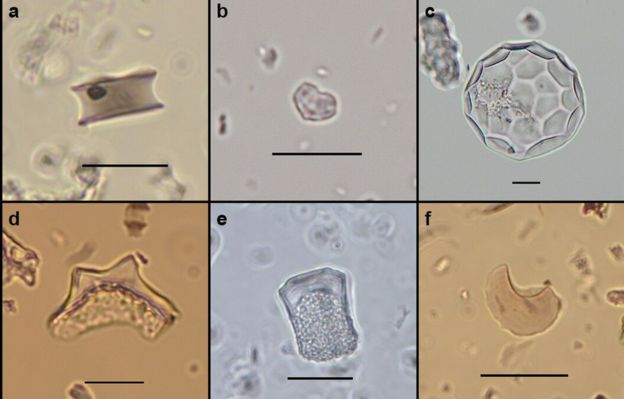

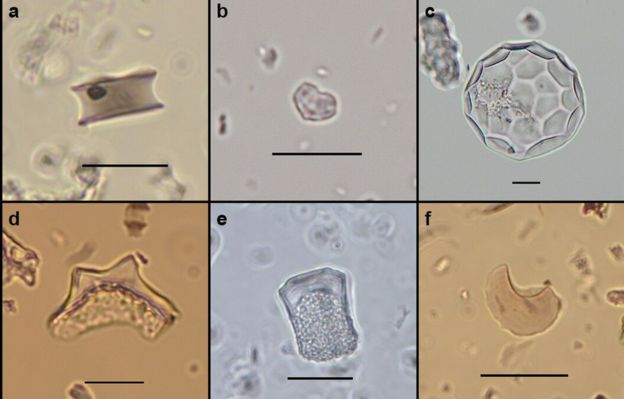

Images of the phytoliths found by the scientists - the scalloped sphere in the top right corner is from squash

Perhaps the most important of these was that early civilisations began to move away from living as hunter-gatherers and started to cultivate crops for food.

Researchers have previously unearthed evidence that crops were domesticated at four important locations around the world.

So China saw the cultivation of rice, while in the Middle East it was grains, in Central America and Mexico it was maize, while potatoes and quinoa emerged in the Andes.

Now scientists say that the Llanos de Moxos region of southwestern Amazonia should be seen as a fifth key region.

The area is a savannah but is dotted with raised areas of land now covered with trees.

Perhaps the most important of these was that early civilisations began to move away from living as hunter-gatherers and started to cultivate crops for food.

Researchers have previously unearthed evidence that crops were domesticated at four important locations around the world.

So China saw the cultivation of rice, while in the Middle East it was grains, in Central America and Mexico it was maize, while potatoes and quinoa emerged in the Andes.

Now scientists say that the Llanos de Moxos region of southwestern Amazonia should be seen as a fifth key region.

The area is a savannah but is dotted with raised areas of land now covered with trees.

UMBERTO LOMBARDO

One of the 4,700 forest islands in this region of Amazonia

The area floods for part of the year but these "forest islands" remain above the waters.

Some 4,700 of these small mounds were developed by humans over time, in a very mundane way.

"These are just places where people dropped their rubbish, and over time they grow," said lead author Dr Umberto Lombardo from the University of Bern, Switzerland.

"Of course, rubbish is very rich in nutrients, and as these areas grow they rise above the level of the flood during the rainy season, so they become good places to settle with fertile soil, so people come back to the same places all the time."

The researchers examined some 30 of these islands for evidence of crop planting.

They discovered tiny fragments of silica called phytoliths, described as tiny pieces of glass that form inside the cells of plants.

The shape of these tiny glass fragments are different, depending on which plants they come from.

The researchers were able to identify evidence of manioc (cassava, yuca) that were grown 10,350 years ago. Squash appears 10,250 years ago, and maize more recently - just 6,850 years ago.

"This is quite surprising," said Dr Lombardo.

The area floods for part of the year but these "forest islands" remain above the waters.

Some 4,700 of these small mounds were developed by humans over time, in a very mundane way.

"These are just places where people dropped their rubbish, and over time they grow," said lead author Dr Umberto Lombardo from the University of Bern, Switzerland.

"Of course, rubbish is very rich in nutrients, and as these areas grow they rise above the level of the flood during the rainy season, so they become good places to settle with fertile soil, so people come back to the same places all the time."

The researchers examined some 30 of these islands for evidence of crop planting.

They discovered tiny fragments of silica called phytoliths, described as tiny pieces of glass that form inside the cells of plants.

The shape of these tiny glass fragments are different, depending on which plants they come from.

The researchers were able to identify evidence of manioc (cassava, yuca) that were grown 10,350 years ago. Squash appears 10,250 years ago, and maize more recently - just 6,850 years ago.

"This is quite surprising," said Dr Lombardo.

UMBERTO LOMBARDO The scientists at work on the site

"This is Amazonia, this is one of these places that a few years ago we thought to be like a virgin forest, an untouched environment."

"Now we're finding this evidence that people were living there 10,500 years ago, and they started practising cultivation."

The people who lived at this time probably also survived on sweet potato and peanuts, as well as fish and large herbivores.

The researchers say it's likely that the humans who lived here may have brought their plants with them.

They believe their study is another example of the global impact of the environmental changes being felt as the world warmed up at the end of the last ice age.

"It's interesting in that it confirms again that domestication begins at the start of the Holocene period, when we have this climate change that we see as we exit from the ice age," said Dr Lombardo.

"We entered this warm period, when all over the world at the same time, people start cultivating."

The study has been published in the journal Nature.

No comments:

Post a Comment