I’m Not Celebrating Long-Overdue Legislation Banning Lynching

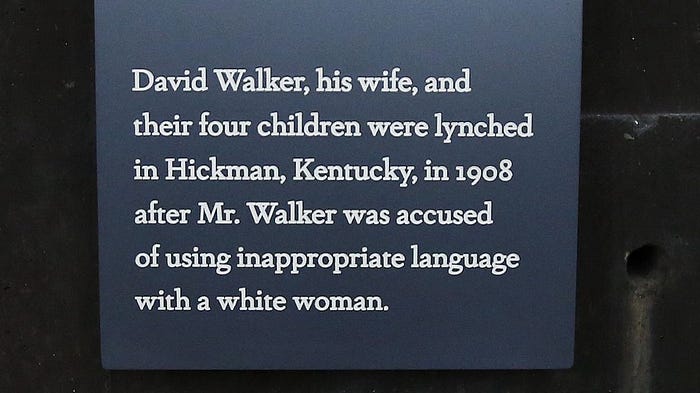

National Memorial for Peace and Justice (Photo: Guy Nave)

National Memorial for Peace and Justice (Photo: Guy Nave)On Monday, March 7, Congress approved legislation banning lynching and making it a federal hate crime. It has only taken 200 attempts to approve such legislation. The bill now goes to President Biden to sign into law.

On April 26, 2018, I attended the opening of the Equal Justice Initiative’s (EJI) Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

The 11,000-square-foot Legacy Museum is built on the site of a former warehouse where enslaved black people were imprisoned. It is located midway between a historic slave market and the main river dock and train station. Slavers trafficked tens of thousands of enslaved black people there during the height of the domestic slave trade.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is a memorial to the victims of “racial terror lynchings.” The site includes a memorial square with 800 six-foot columns that include the names of victims and the counties and states where racial terror lynchings took place.

The columns are suspended from above, representing public lynchings that happened in town squares across America. The hanging columns evoke the image of hanging brown bodies. They force visitors to grapple with the vast number of lynching victims in America.

Photo by Guy Nave

The memorial had a profound impact on me during my visit.

As I found myself surrounded by 800 hanging columns, I was reminded that in 1959 — just four years after 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched in Money, MS — a 17-year-old boy, who would later become my father, was sent from his home in Mississippi to live with his mother’s sister in east central Indiana.

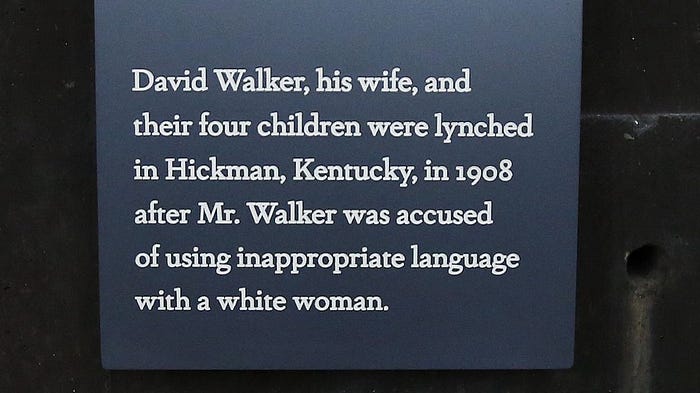

My grandparents feared their eldest son would become another victim of racial terror lynching. White men came to their home one evening accusing my not-yet father of speaking “disrespectfully” to white men earlier. Knowing the repercussions of such accusations and certain the men would return later, my grandparents sent their son away.

The memorial had a profound impact on me during my visit.

As I found myself surrounded by 800 hanging columns, I was reminded that in 1959 — just four years after 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched in Money, MS — a 17-year-old boy, who would later become my father, was sent from his home in Mississippi to live with his mother’s sister in east central Indiana.

My grandparents feared their eldest son would become another victim of racial terror lynching. White men came to their home one evening accusing my not-yet father of speaking “disrespectfully” to white men earlier. Knowing the repercussions of such accusations and certain the men would return later, my grandparents sent their son away.

A memorial plaque

Walking through the memorial, I thought about the suffering Emmet Till experienced. White men abducted Till from his great-uncle’s house and savagely beat him. They mutilated his body, lynched him, and shot him in the head before tossing his body into the Tallahatchie River.

As a student of history, I had read about the brutality inflicted upon Emmet Till. I had often wondered about the severity of his suffering.

The severity of the brutality and suffering, however, became much more palpable to me as I walked through the memorial. I imagined the fate that awaited my father had my grandparents not sent him away to Indiana.

Walking through the memorial, I thought about the suffering Emmet Till experienced. White men abducted Till from his great-uncle’s house and savagely beat him. They mutilated his body, lynched him, and shot him in the head before tossing his body into the Tallahatchie River.

As a student of history, I had read about the brutality inflicted upon Emmet Till. I had often wondered about the severity of his suffering.

The severity of the brutality and suffering, however, became much more palpable to me as I walked through the memorial. I imagined the fate that awaited my father had my grandparents not sent him away to Indiana.

Emmet Till

It’s estimated that more than six million black people fled the South as refugees and exiles as a result of racial terror lynchings.

As a 57-year old African American college professor with graduate degrees from Princeton Theological Seminary and Yale University, I often think about who Emmett Till’s children might have become.

I think about the sheer volume of surviving and unborn descendants of the more than 4,400 black men, women, boys, and girls lynched in America. I think about the legacy of American impoverishment resulting from the barbaric atrocity of lynching.

How many brilliant black people has our nation been denied as a result of lynchings?

Had my grandparents not protected my father from a lynching 63 years ago, I would have never been born.

He would have never brought his nine brothers and sisters out of Mississippi. They may have never provided America with the several dozen children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren who have helped make America a better nation.

Lynchings have not only terrorized black Americans, they have impoverished America as a nation.

We will never be able to imagine the contributions made by the hundreds of thousands of black Americans denied an opportunity to impact the world because of lynchings.

While making plans four years ago to attend the opening of the museum and memorial, several white people asked me, “What is the benefit of a museum and a memorial dedicated to the victims of slavery and lynching?”

As someone who teaches about the ongoing legacy of racism, I’ve often had white people ask me, “Why do black people insist on living in the past and remembering slavery when we have come so far as a nation?”

Americans are extremely selective regarding the past we teach and reflect upon. Many Americans invoke a selective past in order to buttress a racist self-serving present.

Much of the recent rhetoric and legislation banning the teaching of critical race theory has nothing to do with CRT. It’s about allowing for a teaching of history that denies the realities and legacies of racial oppression in America.

As eloquently stated on the EJI webpage,

A history of racial injustice must be acknowledged, and mass atrocities and abuse must be recognized and remembered, before a society can recover from mass violence.

I learned very little during my public school education about the history of slavery, racism, and lynching in America.

The concerted efforts to ban public school teaching about systemic racism and the consequences of slavery ensure students continue to learn very little about this history.

I am glad the U.S. Congress has finally passed legislation banning lynching in America. Welcome to the 21st century!

While I expect President Biden to sign the bill into law, I’m not celebrating the legislation.

In many ways the passage of this legislation has more symbolic significance than practical significance.

Passing long-overdue legislation banning lynching rings hollow when we are passing legislation banning teaching about lynching in public schools.

Current and future generations of Americans need to know why the passage of this legislation is important.

Promoting teaching about racism, slavery, and lynchings in public schools might help ensure the importance of this legislation is understood.

It also might help pave the way for the passage of legislation addressing current acts of systemic racial violence and injustice. It could even possibly prevent having to wait 150 years before passing the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

It’s estimated that more than six million black people fled the South as refugees and exiles as a result of racial terror lynchings.

As a 57-year old African American college professor with graduate degrees from Princeton Theological Seminary and Yale University, I often think about who Emmett Till’s children might have become.

I think about the sheer volume of surviving and unborn descendants of the more than 4,400 black men, women, boys, and girls lynched in America. I think about the legacy of American impoverishment resulting from the barbaric atrocity of lynching.

How many brilliant black people has our nation been denied as a result of lynchings?

Had my grandparents not protected my father from a lynching 63 years ago, I would have never been born.

He would have never brought his nine brothers and sisters out of Mississippi. They may have never provided America with the several dozen children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren who have helped make America a better nation.

Lynchings have not only terrorized black Americans, they have impoverished America as a nation.

We will never be able to imagine the contributions made by the hundreds of thousands of black Americans denied an opportunity to impact the world because of lynchings.

While making plans four years ago to attend the opening of the museum and memorial, several white people asked me, “What is the benefit of a museum and a memorial dedicated to the victims of slavery and lynching?”

As someone who teaches about the ongoing legacy of racism, I’ve often had white people ask me, “Why do black people insist on living in the past and remembering slavery when we have come so far as a nation?”

Americans are extremely selective regarding the past we teach and reflect upon. Many Americans invoke a selective past in order to buttress a racist self-serving present.

Much of the recent rhetoric and legislation banning the teaching of critical race theory has nothing to do with CRT. It’s about allowing for a teaching of history that denies the realities and legacies of racial oppression in America.

As eloquently stated on the EJI webpage,

A history of racial injustice must be acknowledged, and mass atrocities and abuse must be recognized and remembered, before a society can recover from mass violence.

I learned very little during my public school education about the history of slavery, racism, and lynching in America.

The concerted efforts to ban public school teaching about systemic racism and the consequences of slavery ensure students continue to learn very little about this history.

I am glad the U.S. Congress has finally passed legislation banning lynching in America. Welcome to the 21st century!

While I expect President Biden to sign the bill into law, I’m not celebrating the legislation.

In many ways the passage of this legislation has more symbolic significance than practical significance.

Passing long-overdue legislation banning lynching rings hollow when we are passing legislation banning teaching about lynching in public schools.

Current and future generations of Americans need to know why the passage of this legislation is important.

Promoting teaching about racism, slavery, and lynchings in public schools might help ensure the importance of this legislation is understood.

It also might help pave the way for the passage of legislation addressing current acts of systemic racial violence and injustice. It could even possibly prevent having to wait 150 years before passing the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

Guy Nave

Lover of life, professor, speaker, author, blogger, social activist, founder of www.ClamoringforChange.com. Committed to promoting civil dialogue and engagement

No comments:

Post a Comment