Sun, January 29, 2023

By Joey Roulette

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The discovery of an asteroid the size of a small shipping truck mere days before it passed Earth on Thursday, albeit one that posed no threat to humans, highlights a blind spot in our ability to predict those that could actually cause damage, astronomers say.

NASA for years has prioritized detecting asteroids much bigger and more existentially threatening than 2023 BU, the small space rock that streaked by 2,200 miles from the Earth's surface, closer than some satellites. If bound for Earth, it would have been pulverized in the atmosphere, with only small fragments possibly reaching land.

But 2023 BU sits on the smaller end of a size group, asteroids 5-to-50 meters in diameter, that also includes those as big as an Olympic swimming pool. Objects that size are difficult to detect until they wander much closer to Earth, complicating any efforts to brace for one that could impact a populated area.

The probability of an Earth impact by a space rock, called a meteor when it enters the atmosphere, of that size range is fairly low, scaling according to the asteroid's size: a 5-meter rock is estimated to target Earth once a year, and a 50-meter rock once every thousand years, according to NASA.

But with current capabilities, astronomers can't see when such a rock targets Earth until days prior.

"We don't know where most of the asteroids are that can cause local to regional devastation," said Terik Daly, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory.

The roughly 20-meter meteor that exploded in 2013 over Chelyabinsk, Russia is a once-every-100-years event, according to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It created a shockwave that shattered tens of thousands of windows and caused $33 million in damage, and no one saw it coming before it entered Earth's atmosphere.

Some astronomers consider relying only on statistical probabilities and estimates of asteroid populations an unnecessary risk, when improvements could be made to NASA's ability to detect them.

"How many natural hazards are there that we could actually do something about and prevent for a billion dollars? There's not many," said Daly, whose work focuses on defending Earth from hazardous asteroids.

AVOIDING A REALLY BAD DAY

One major upgrade to NASA's detection arsenal will be NEO Surveyor, a $1.2 billion telescope under development that will launch nearly a million miles from Earth and surveil a wide field of asteroids. It promises a significant advantage over today's ground-based telescopes that are hindered by daytime light and Earth's atmosphere.

That new telescope will help NASA meet a goal assigned by Congress in 2005: detect 90% of the total expected amount of asteroids bigger than 140 meters, or those big enough to destroy anything from a region to an entire continent.

"With Surveyor, we're really focusing on finding the one asteroid that could cause a really bad day for a lot of people," said Amy Mainzer, NEO Surveyor principal investigator. "But we're also tasked with getting good statistics on the smaller objects, down to about the size of the Chelyabinsk object."

NASA has fallen years behind on its congressional goal, which was ordered for completion by 2020. The agency proposed last year to cut the telescope's 2023 budget by three quarters and a two-year launch delay to 2028 "to support higher-priority missions" elsewhere in NASA's science portfolio.

Asteroid detection gained greater importance last year after NASA slammed a refrigerator-sized spacecraft into an asteroid to test its ability to knock a potentially hazardous space rock off a collision course with Earth.

The successful demonstration, called the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), affirmed for the first time a method of planetary defense.

"NEO Surveyor is of the utmost importance, especially now that we know from DART that we really can do something about it," Daly said.

"So by golly, we gotta find these asteroids."

(Reporting by Joey Roulette; Editing by Andrea Ricci)

A small asteroid swung past Earth Thursday night, in one of the closest flybys we've ever seen.

On January 21, 2023, Gennadiy Borisov, the same amateur astronomer who found the first interstellar comet, spotted a new asteroid flying towards our planet. Now named 2023 BU, this roughly 5-metre-wide space rock is one of 115 asteroids discovered so far this year that come reasonably close to our world. This particular near-Earth asteroid has earned a special distinction, though.

Based on the observations made by Borisov and other astronomers around the world, NASA's system for analyzing the impact threat of asteroids — Scout — found that it would be a safe pass, but an extremely close one!

"Scout quickly ruled out 2023 BU as an impactor, but despite the very few observations, it was nonetheless able to predict that the asteroid would make an extraordinarily close approach with Earth," Davide Farnocchia, the NASA JPL engineer who developed Scout, said in a press release. "In fact, this is one of the closest approaches by a known near-Earth object ever recorded."

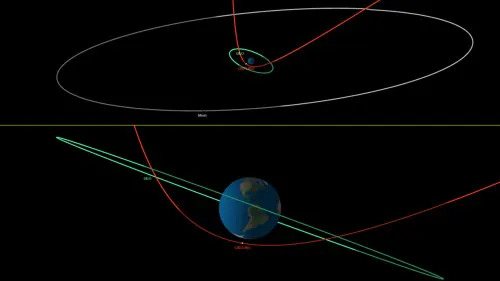

These diagrams show the orbit of asteroid 2023 BU in relation to the Earth, the ring of geostationary satellites (green), and the orbit of the Moon (gray) — the top view from beyond the Moon's orbit, and the bottom from beyond geostationary orbit. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Scott Sutherland

At 7:27 p.m. EST on Thursday, January 26, 2023 BU passed over the southern tip of South America at an altitude of around 3,600 kilometres above the surface.

For a sense of scale, that's around 9 times farther away than the orbit of the International Space Station. However, it's also about one-tenth the distance to the ring of geostationary weather and communication satellites that circle the planet, and over 100 times closer than the Moon.

According to NASA, Earth's gravity affects every asteroid that comes close to the planet. 2023 BU is coming so close, though, that it will experience a significant change in its orbit around the Sun.

"Before encountering Earth, the asteroid's orbit around the Sun was roughly circular, approximating Earth's orbit, taking 359 days to complete its orbit about the Sun," the space agency said. "After its encounter, the asteroid's orbit will be more elongated, moving it out to about halfway between Earth's and Mars' orbits at its farthest point from the Sun. The asteroid will then complete one orbit every 425 days."

No risk from 2023 BU

Both NASA and the European Space Agency have gone on record saying that there was no threat of an impact from asteroid 2023 BU.

In fact, the discovery of this asteroid shows how far we've come in the field of planetary defence.

"2023 BU was discovered about a week ago. Although it doesn't seem like much warning, the advance detection of this very small — and safe — asteroid, shows just how much detection technologies are improving," the ESA said.

Spotted!!

As predicted, 2023 BU skimmed by Earth, right on schedule!

The predictions of its trajectory were so accurate that a robotic camera run by the Virtual Telescope Project picked up the tiny visitor during its closest pass.

This stands as another fantastic example of how far we've come with our ability to detect and track asteroids.

In November, astronomers spotted an even smaller object, a meteoroid less than a metre wide named 2022 WJ1, just three hours before it plunged into the atmosphere to burn up over Southwestern Ontario. The hunt for meteorites from this event is still ongoing.

No comments:

Post a Comment