Religion historian tries to understand the mysterious force.

(RNS) — In her recent book, 'Spellbound,' Molly Worthen posits that charismatic people tell a compelling story about human identity and purpose that others gravitate to because it helps explain their own role in the grand scheme of life.

Leaders including Oprah Winfrey, clockwise from top left, Joseph Smith, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and President Donald Trump are highlighted in “Spellbound: How Charisma Shaped American History from the Puritans to Donald Trump.” (AP and RNS file photos)

Yonat Shimron

July 25, 2025

RNS

(RNS) — What drives people to follow a leader and place their faith in that person’s story? That question is at the heart of religion historian and journalist Molly Worthen’s latest book, “Spellbound: How Charisma Shaped American History from the Puritans to Donald Trump.”

Worthen, a history professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, describes being fascinated by the qualities that help explain charismatic leadership. In her book, released in May, she posits that charismatic people tell a compelling story about human identity and purpose that others gravitate toward because it helps explain their own role in the grand scheme of life.

Understanding charisma is therefore, a way to understand the religious quest.

In her book, Worthen writes about leaders across 400 years of United States history who served as magnets for multitudes. Among the dozens portrayed are Shaker leader Mother Ann Lee, Native American Shawnee Chief Tecumseh, Mormon founder Joseph Smith, President Andrew Jackson, civil rights leader the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Indian-American guru Maharaj Ji, media mogul Oprah Winfrey, and yes, Donald Trump. Some are what she calls apocalyptic destroyers, others are institution builders. Some are beautiful, others are physically repulsive, yet all are alluring because they invite followers into a story that offers them meaning, a glimpse into a hidden reality, and a sense of security and assurance.

Even as Americans’ trust in religious and governmental institutions has collapsed over the past few decades, their religious impulses and their search for ultimate meaning are alive and kicking. As Worthen posits, we may even be at the start of an old-fashioned religious revival.

RNS talked with Worthen about her book and the mysterious quality of charisma that bewitches people who gravitate toward certain leaders. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

“Spellbound: How Charisma Shaped American History from the Puritans to Donald Trump” and author Molly Worthen. (Courtesy images)

You’re both a scholar and journalist who writes frequently about religion. Who did you intend this book for?

I intended it for people who are interested in American history and, like me, scratching their heads about the current political scene. The genesis of the project was about nine or 10 years ago when I was trying to make sense of the rise of Donald Trump and to think through how one individual could provoke such diametrically opposed reactions from different swaths of the country. How could one guy totally repel so many people, but also be so magnetic for other people?

I was also thinking about the way we use the word charisma. People punt to the word charisma when they are observing a phenomenon and they’re not really sure what’s going on — they can’t really account for the appeal of this person by ordinary policy proposals. I think it’s a set of questions that have pretty broad application beyond the academic study of history, which is why I wrote it for a trade press and tried to do it in a character-focused narrative style.

Is the core of your argument that the theory of growing secularization is wrong?

It’s contested. I always try to get my students to understand that secularization is the story of the decline of Western individuals’ relationships with institutions in general, including religious institutions. I absolutely think that secularization describes a real phenomenon. I’m not persuaded that it describes a radical change in what I see to be pretty essential desires and anxieties that humans have had across the centuries. I’m pushing back against the sense that religion is declining in some grand sense and we’re all becoming more rational and see the world purely through a material lens.

Your book offers a panoramic look at 400 years of history. How did you decide which charismatic figures to write about?

It was really hard. Every time I would tell someone about the project, they would say, ‘Oh, are you including X, Y and Z person?’ There’s an almost endless list. I tried to identify particular patterns in history, individuals whose stories would help bring forward those patterns, as well as try to offer the reader a mix of characters. I felt I had to have a certain number of people who are markers in the American historical narrative, combined with less expected figures who show the interweaving of religion and politics. It’s an art and not a science. I’m sure I could have written other versions of the book with wholly different characters.

I did make the decision to focus on religion and politics, not because I think that charisma doesn’t show up in other forums, but because I’m telling a story about the way a particular kind of storytelling yields a kind of power over people that is easiest to see in the spheres of religion and politics. One of my arguments is that we confuse charisma with charm and celebrity. I think it’s important to distinguish them. Much of what people use charisma to describe in these other spheres is better captured in discussions about celebrity.

It seems like all the different types of charismatic leaders you portray converge in Trump. Do you see that?

I struggled with the role of Trump in the story because on the one hand, the project began as an effort to try to explain him, but I don’t see him as the culmination of four centuries of American history. Rather, I think understanding the patterns that stretch across four centuries of history helps us contextualize Trump. There are certain ways in which he is sui generis. At the same time, Trump’s success as a political leader is in continuity with earlier episodes in American history and with this destructive impulse that we see in some leaders to tear down established traditions and institutions. In our own moment, institutions are weaker than they have ever been, and Americans are more atomized and isolated than ever, disconnected from various communities that used to anchor us. And so, I think that there is scope for a charismatic leader who has a gift for offering a counter narrative that further erodes institutional authority to really gain more power than perhaps was possible in the past.

I think, too, that Trump has a real gift for telling a story about himself that then gets woven into a story about the country. He’s always talking about how people are constantly trying to screw him over and everything is a scam; the whole system is rigged. It flows so cleanly into the story he begins telling about how America is getting screwed over. So it’s kind of easy for him to become the avatar for people who increasingly feel excluded from the kind of economic gains of globalization.

I also think he is in no way an orthodox Christian. He grew up going to Norman Vincent Peale’s church in New York City. His native spiritual tradition, which I think is very sincerely ingrained in him, is the power of positive thinking. You could argue it’s one of the dominant spiritual traditions within Christianity in America — this sense that we can manifest the future that we want to see. That’s very much Trump’s spiritual formation. His connections with some conservative Christian representatives of that, like Paula White-Cain, long predate his formal interest in politics.

Many of these strands do come together in Trump, but I guess I want to resist aggrandizing him too much. But I do think his charismatic storytelling ability, his gift for convincing followers that he will pull back the veil on a picture of the world that the elites have been keeping you from seeing all this time, I think that is really appealing and helps us explain the support of his base.

You spent a bit of time on some leaders of the New Apostolic Reformation. Do you think there is a kind of apocalyptic revival happening today and do you see them as leading that?

It is interesting how Trump has awakened outside observers to the presence of these independent charismatic churches. They’ve always been really big, but now we’re finally paying attention. The more I learn about the NAR, the more I’m struck by its internal diversity. I do think there’s been a problem in the reductionist account of the NAR as this sort of unified army of foot soldiers. There are some leaders and congregations in this subculture that are very politically activated, Others are focused on missions and quite politically mixed. It’s such a slippery phenomenon because they’re not denominations with a normal hierarchy. They’re networks. They’re global. The average secular person expects to find white supremacists. It’s not what you see at all in many of these churches.

I think that there are real hazards though. These very independent churches are averse to the traditional hierarchies, averse to having pastors with degrees from traditional seminaries, skeptical of institutions, which has been a feature of modern Pentecostalism and charismatic churches since they began as a real movement more than 100 years ago. There’s a way in which that belief that you are receiving a message directly from God, unencumbered by checks and balances from a sober institution can empower radical activity. That’s a powerful, activated frame of mind, that when allied with the incredible strategic savvy of the second Trump administration can yield very serious political consequences.

You talk in the book about two kinds of charismatic figures: the apocalyptic destroyers and the institution builders. I guess it’s possible an institution builder could emerge again in the future, right?

I think that charisma by itself is morally neutral. It doesn’t carry with it inherently a moral valence, so I think the lens of charisma helps us understand Martin Luther King, and it helps us understand Hitler. The difference is whether the story that the charismatic leader is telling is anchored in empirical fact. So you can tell a true story, or you can tell one that is full of lies and manipulations. That’s an important distinction.

I also think charismatic leaders who ultimately serve moral progress have healthy relationships to institutions and checks and balances and structures of accountability. There’s a limit on the authority they accrue to themselves as individuals. The American left is struggling with the grand narrative problem that can truly be a counterweight to the MAGA story, but that isn’t to say that it can’t happen. I do think that maybe these little signs of heightened interest in the stability of institutions and the connections they offer to the deep past may indeed indicate a hunger for a leader who tends in that direction. I hope.

Conference explores spiritual care as resistance to US political situation

CHICAGO (RNS) — While IASC has an international focus, many references were made throughout the annual conference to the current political moment in the United States.

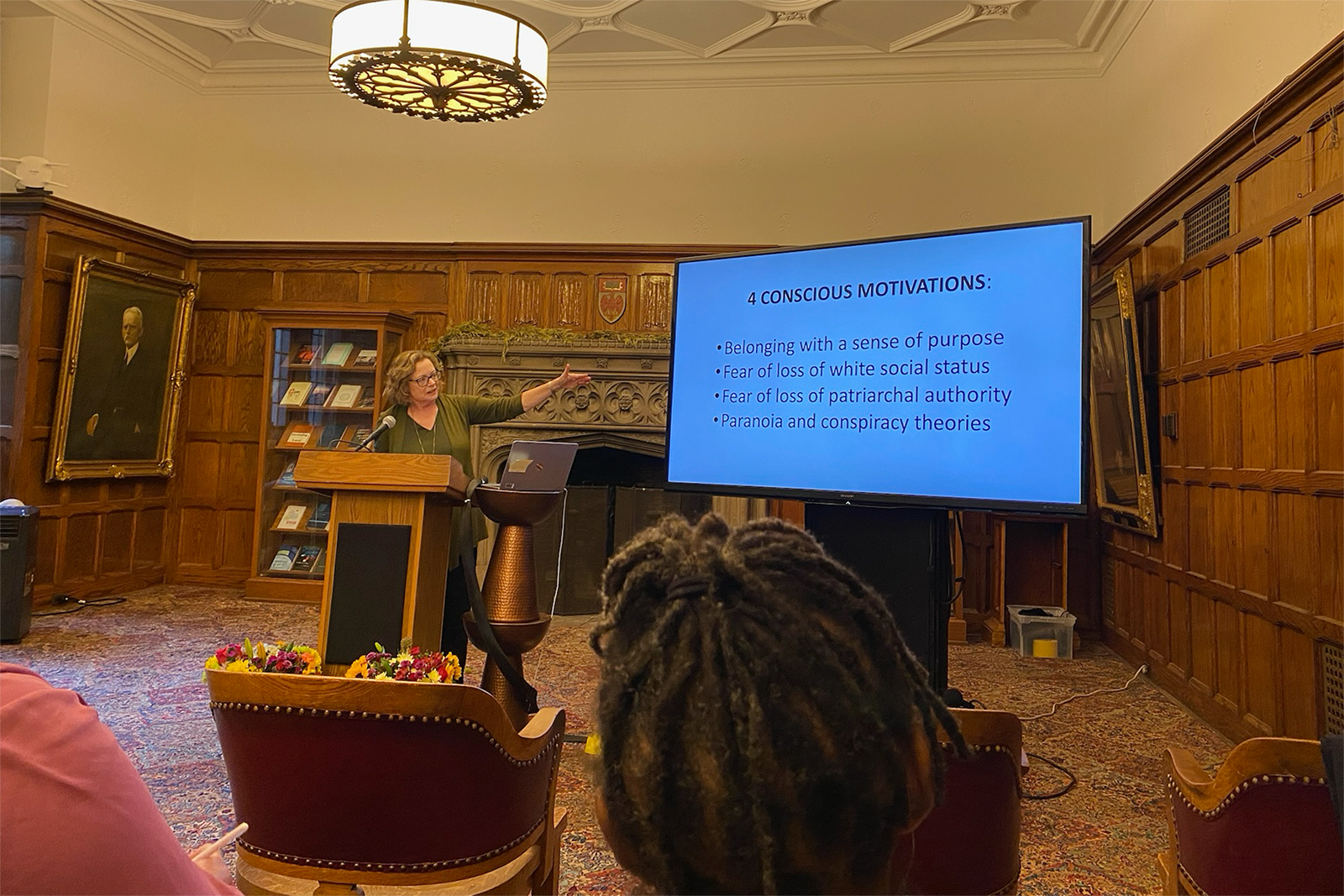

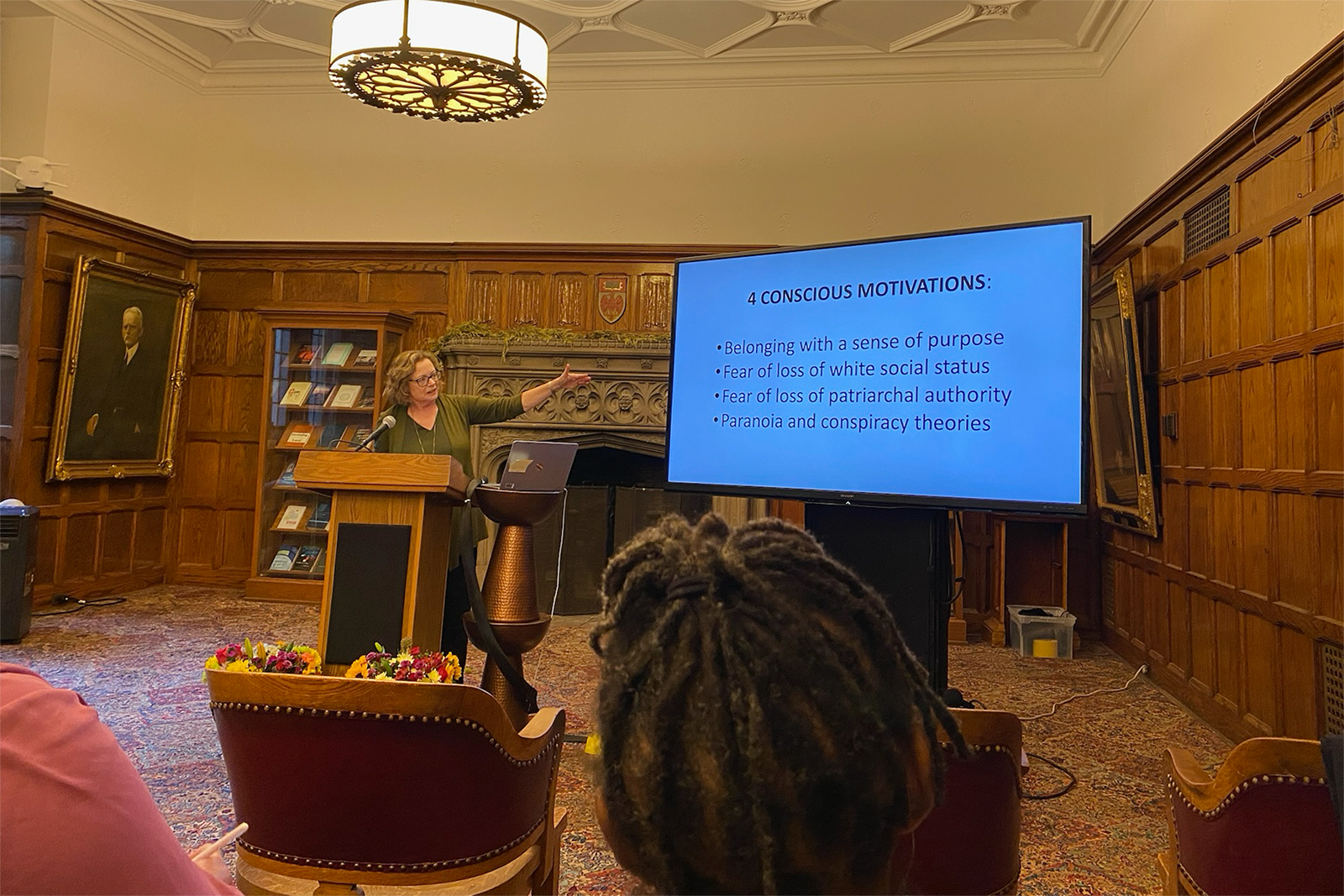

The Rev. Pamela Cooper-White presents a lecture titled “Spiritual Care as Resistance: Christian Nationalism, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Authoritarianism," Sunday, July 20, 2025, during the International Association for Spiritual Care annual meeting in Chicago. (Photo by Rachel Berkebile)

Rachel Berkebile

July 25, 2025

CHICAGO (RNS) — The International Association for Spiritual Care met in Chicago for its annual conference from July 20-22, under the theme “spiritual care as resistance,” which focused on how to address the current political moment through the field’s expertise.

About 50 people attended the conference, both in person and online, including pastoral care scholars, hospital chaplains and clergy. The attendees from at least four continents represented a variety of faith traditions, including Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, paganism and those of no religion.

In contemplating spiritual care as resistance, speakers covered topics from religious trauma and how to heal it, to how spiritual care can be used for groups rather than just individuals, to how to embody one’s values of care and justice when they go against a larger system. While IASC has an international focus, many panelists referenced the current political moment in the United States throughout the conference.

The Rev. Pamela Cooper-White, IASC founding member and former president, set the tone with her public lecture on Sunday evening titled, “Spiritual Care as Resistance: Christian Nationalism, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Authoritarianism.”

“This is probably the angriest talk I’ve ever given,” she said. “U.S. President Donald Trump and his loyalists have taken a wrecking ball to virtually everything touching on racial, gender and climate justice that most, if not all, of us here have worked on for decades. And the consequences are dire and potentially long-lasting.”

Cooper-White’s 2022 book, “The Psychology of Christian Nationalism: Why People Are Drawn In and How to Talk Across the Divide” was featured heavily in her lecture as she unpacked how she sees Christian nationalism affecting the American political landscape. She concluded with a call to action.

“The current escalating racist attacks on immigrants and people of color, LGBTQ persons, and the blatant reversal of environmental protections, call us to consider spiritual care as resistance,” she said. “We have engaged personally in practices of resistance in our own communities, but we perhaps need more collective, political and policy-oriented action. … As an international and explicitly interreligious organization, we as members of IASC have the knowledge and the power collectively to make a more public witness against all that we see is eroding the cultural and religious values that undergird our work of care.”

Spiritual care, sometimes referred to as pastoral care, has many overlaps with therapy or counseling, both taking place in a one-on-one setting between a care seeker and provider. However, instead of caring for one’s mind like in therapy, spiritual care focuses on one’s soul, centering the care seeker’s personal lived theology. Historically, most think of chaplains or those who commonly work in hospitals, prisons and with the military as performing this work. But spiritual care is also central to the work of spiritual directors and most clergy.

IASC, which was founded in 2015 in Bern, Switzerland, aims to enhance the capacities of spiritual care scholars and practitioners in acquiring, disseminating and applying knowledge of theory and practice of the field, and emphasizes interdisciplinary, interreligious and intercultural scholarly investigation, according to its mission statement.

The group began as a nonprofit, but in 2023, the board decided to drop its nonprofit status. Since then, it has operated as a volunteer-only organization. The board members at the time of the switch realized that what the association was best at was putting on the annual conference and creating books from the content, Cooper-White said. They wanted to make the annual conferences their focus, rather than collecting members and dues.

One of IASC’s books is “What Is Spiritual Care?” in which contributors in various caregiving professions, religious traditions and cultural contexts offered their answer to the question. “The cumulative impact of this work emphasizes that spiritual care is inseparable from larger efforts towards justice and peacemaking,” IASC said of the book on its website.

The Rev. Cynthia Linder, from left, leads a panel discussion on the book, “What Is Spiritual Care?” with Rabbi Mychal Springer, the Rev. Pamela Cooper-White, Daniel Schipani, president of IASC, and Mahmoud Abdallah, Tuesday, July 22, 2025, in Chicago. (Photo by Rachel Berkebile)

Members of the IASC board, including its president, Daniel Schipani, and contributors to the book spoke about the question on a panel, discussing the importance of and challenges around their attempts to maintain a broad, international and interfaith definition of spiritual care.

Each speaker on the panel offered their definition of spiritual care. Rabbi Mychal Springer, who founded the Center for Pastoral Education at Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City, said spiritual care is the “work of sustaining people in the spirit.”

Schipani’s definition included spiritual care as “a compassionate response to human suffering.” While Mahmoud Abdallah, an academic staff member at the Center for Islamic Theology at the University of Tübingen in Germany, said the field of spiritual care “is still open to design.” The panelists seemed to agree on the importance of community in doing the work of pastoral care and that it is not work that can be done alone.

(RNS) — In her recent book, 'Spellbound,' Molly Worthen posits that charismatic people tell a compelling story about human identity and purpose that others gravitate to because it helps explain their own role in the grand scheme of life.

Leaders including Oprah Winfrey, clockwise from top left, Joseph Smith, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and President Donald Trump are highlighted in “Spellbound: How Charisma Shaped American History from the Puritans to Donald Trump.” (AP and RNS file photos)

Yonat Shimron

July 25, 2025

RNS

(RNS) — What drives people to follow a leader and place their faith in that person’s story? That question is at the heart of religion historian and journalist Molly Worthen’s latest book, “Spellbound: How Charisma Shaped American History from the Puritans to Donald Trump.”

Worthen, a history professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, describes being fascinated by the qualities that help explain charismatic leadership. In her book, released in May, she posits that charismatic people tell a compelling story about human identity and purpose that others gravitate toward because it helps explain their own role in the grand scheme of life.

Understanding charisma is therefore, a way to understand the religious quest.

In her book, Worthen writes about leaders across 400 years of United States history who served as magnets for multitudes. Among the dozens portrayed are Shaker leader Mother Ann Lee, Native American Shawnee Chief Tecumseh, Mormon founder Joseph Smith, President Andrew Jackson, civil rights leader the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Indian-American guru Maharaj Ji, media mogul Oprah Winfrey, and yes, Donald Trump. Some are what she calls apocalyptic destroyers, others are institution builders. Some are beautiful, others are physically repulsive, yet all are alluring because they invite followers into a story that offers them meaning, a glimpse into a hidden reality, and a sense of security and assurance.

Even as Americans’ trust in religious and governmental institutions has collapsed over the past few decades, their religious impulses and their search for ultimate meaning are alive and kicking. As Worthen posits, we may even be at the start of an old-fashioned religious revival.

RNS talked with Worthen about her book and the mysterious quality of charisma that bewitches people who gravitate toward certain leaders. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

“Spellbound: How Charisma Shaped American History from the Puritans to Donald Trump” and author Molly Worthen. (Courtesy images)

You’re both a scholar and journalist who writes frequently about religion. Who did you intend this book for?

I intended it for people who are interested in American history and, like me, scratching their heads about the current political scene. The genesis of the project was about nine or 10 years ago when I was trying to make sense of the rise of Donald Trump and to think through how one individual could provoke such diametrically opposed reactions from different swaths of the country. How could one guy totally repel so many people, but also be so magnetic for other people?

I was also thinking about the way we use the word charisma. People punt to the word charisma when they are observing a phenomenon and they’re not really sure what’s going on — they can’t really account for the appeal of this person by ordinary policy proposals. I think it’s a set of questions that have pretty broad application beyond the academic study of history, which is why I wrote it for a trade press and tried to do it in a character-focused narrative style.

Is the core of your argument that the theory of growing secularization is wrong?

It’s contested. I always try to get my students to understand that secularization is the story of the decline of Western individuals’ relationships with institutions in general, including religious institutions. I absolutely think that secularization describes a real phenomenon. I’m not persuaded that it describes a radical change in what I see to be pretty essential desires and anxieties that humans have had across the centuries. I’m pushing back against the sense that religion is declining in some grand sense and we’re all becoming more rational and see the world purely through a material lens.

Your book offers a panoramic look at 400 years of history. How did you decide which charismatic figures to write about?

It was really hard. Every time I would tell someone about the project, they would say, ‘Oh, are you including X, Y and Z person?’ There’s an almost endless list. I tried to identify particular patterns in history, individuals whose stories would help bring forward those patterns, as well as try to offer the reader a mix of characters. I felt I had to have a certain number of people who are markers in the American historical narrative, combined with less expected figures who show the interweaving of religion and politics. It’s an art and not a science. I’m sure I could have written other versions of the book with wholly different characters.

I did make the decision to focus on religion and politics, not because I think that charisma doesn’t show up in other forums, but because I’m telling a story about the way a particular kind of storytelling yields a kind of power over people that is easiest to see in the spheres of religion and politics. One of my arguments is that we confuse charisma with charm and celebrity. I think it’s important to distinguish them. Much of what people use charisma to describe in these other spheres is better captured in discussions about celebrity.

It seems like all the different types of charismatic leaders you portray converge in Trump. Do you see that?

I struggled with the role of Trump in the story because on the one hand, the project began as an effort to try to explain him, but I don’t see him as the culmination of four centuries of American history. Rather, I think understanding the patterns that stretch across four centuries of history helps us contextualize Trump. There are certain ways in which he is sui generis. At the same time, Trump’s success as a political leader is in continuity with earlier episodes in American history and with this destructive impulse that we see in some leaders to tear down established traditions and institutions. In our own moment, institutions are weaker than they have ever been, and Americans are more atomized and isolated than ever, disconnected from various communities that used to anchor us. And so, I think that there is scope for a charismatic leader who has a gift for offering a counter narrative that further erodes institutional authority to really gain more power than perhaps was possible in the past.

I think, too, that Trump has a real gift for telling a story about himself that then gets woven into a story about the country. He’s always talking about how people are constantly trying to screw him over and everything is a scam; the whole system is rigged. It flows so cleanly into the story he begins telling about how America is getting screwed over. So it’s kind of easy for him to become the avatar for people who increasingly feel excluded from the kind of economic gains of globalization.

I also think he is in no way an orthodox Christian. He grew up going to Norman Vincent Peale’s church in New York City. His native spiritual tradition, which I think is very sincerely ingrained in him, is the power of positive thinking. You could argue it’s one of the dominant spiritual traditions within Christianity in America — this sense that we can manifest the future that we want to see. That’s very much Trump’s spiritual formation. His connections with some conservative Christian representatives of that, like Paula White-Cain, long predate his formal interest in politics.

Many of these strands do come together in Trump, but I guess I want to resist aggrandizing him too much. But I do think his charismatic storytelling ability, his gift for convincing followers that he will pull back the veil on a picture of the world that the elites have been keeping you from seeing all this time, I think that is really appealing and helps us explain the support of his base.

You spent a bit of time on some leaders of the New Apostolic Reformation. Do you think there is a kind of apocalyptic revival happening today and do you see them as leading that?

It is interesting how Trump has awakened outside observers to the presence of these independent charismatic churches. They’ve always been really big, but now we’re finally paying attention. The more I learn about the NAR, the more I’m struck by its internal diversity. I do think there’s been a problem in the reductionist account of the NAR as this sort of unified army of foot soldiers. There are some leaders and congregations in this subculture that are very politically activated, Others are focused on missions and quite politically mixed. It’s such a slippery phenomenon because they’re not denominations with a normal hierarchy. They’re networks. They’re global. The average secular person expects to find white supremacists. It’s not what you see at all in many of these churches.

I think that there are real hazards though. These very independent churches are averse to the traditional hierarchies, averse to having pastors with degrees from traditional seminaries, skeptical of institutions, which has been a feature of modern Pentecostalism and charismatic churches since they began as a real movement more than 100 years ago. There’s a way in which that belief that you are receiving a message directly from God, unencumbered by checks and balances from a sober institution can empower radical activity. That’s a powerful, activated frame of mind, that when allied with the incredible strategic savvy of the second Trump administration can yield very serious political consequences.

You talk in the book about two kinds of charismatic figures: the apocalyptic destroyers and the institution builders. I guess it’s possible an institution builder could emerge again in the future, right?

I think that charisma by itself is morally neutral. It doesn’t carry with it inherently a moral valence, so I think the lens of charisma helps us understand Martin Luther King, and it helps us understand Hitler. The difference is whether the story that the charismatic leader is telling is anchored in empirical fact. So you can tell a true story, or you can tell one that is full of lies and manipulations. That’s an important distinction.

I also think charismatic leaders who ultimately serve moral progress have healthy relationships to institutions and checks and balances and structures of accountability. There’s a limit on the authority they accrue to themselves as individuals. The American left is struggling with the grand narrative problem that can truly be a counterweight to the MAGA story, but that isn’t to say that it can’t happen. I do think that maybe these little signs of heightened interest in the stability of institutions and the connections they offer to the deep past may indeed indicate a hunger for a leader who tends in that direction. I hope.

CHICAGO (RNS) — While IASC has an international focus, many references were made throughout the annual conference to the current political moment in the United States.

The Rev. Pamela Cooper-White presents a lecture titled “Spiritual Care as Resistance: Christian Nationalism, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Authoritarianism," Sunday, July 20, 2025, during the International Association for Spiritual Care annual meeting in Chicago. (Photo by Rachel Berkebile)

Rachel Berkebile

July 25, 2025

CHICAGO (RNS) — The International Association for Spiritual Care met in Chicago for its annual conference from July 20-22, under the theme “spiritual care as resistance,” which focused on how to address the current political moment through the field’s expertise.

About 50 people attended the conference, both in person and online, including pastoral care scholars, hospital chaplains and clergy. The attendees from at least four continents represented a variety of faith traditions, including Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, paganism and those of no religion.

In contemplating spiritual care as resistance, speakers covered topics from religious trauma and how to heal it, to how spiritual care can be used for groups rather than just individuals, to how to embody one’s values of care and justice when they go against a larger system. While IASC has an international focus, many panelists referenced the current political moment in the United States throughout the conference.

The Rev. Pamela Cooper-White, IASC founding member and former president, set the tone with her public lecture on Sunday evening titled, “Spiritual Care as Resistance: Christian Nationalism, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Authoritarianism.”

“This is probably the angriest talk I’ve ever given,” she said. “U.S. President Donald Trump and his loyalists have taken a wrecking ball to virtually everything touching on racial, gender and climate justice that most, if not all, of us here have worked on for decades. And the consequences are dire and potentially long-lasting.”

Cooper-White’s 2022 book, “The Psychology of Christian Nationalism: Why People Are Drawn In and How to Talk Across the Divide” was featured heavily in her lecture as she unpacked how she sees Christian nationalism affecting the American political landscape. She concluded with a call to action.

“The current escalating racist attacks on immigrants and people of color, LGBTQ persons, and the blatant reversal of environmental protections, call us to consider spiritual care as resistance,” she said. “We have engaged personally in practices of resistance in our own communities, but we perhaps need more collective, political and policy-oriented action. … As an international and explicitly interreligious organization, we as members of IASC have the knowledge and the power collectively to make a more public witness against all that we see is eroding the cultural and religious values that undergird our work of care.”

Spiritual care, sometimes referred to as pastoral care, has many overlaps with therapy or counseling, both taking place in a one-on-one setting between a care seeker and provider. However, instead of caring for one’s mind like in therapy, spiritual care focuses on one’s soul, centering the care seeker’s personal lived theology. Historically, most think of chaplains or those who commonly work in hospitals, prisons and with the military as performing this work. But spiritual care is also central to the work of spiritual directors and most clergy.

IASC, which was founded in 2015 in Bern, Switzerland, aims to enhance the capacities of spiritual care scholars and practitioners in acquiring, disseminating and applying knowledge of theory and practice of the field, and emphasizes interdisciplinary, interreligious and intercultural scholarly investigation, according to its mission statement.

The group began as a nonprofit, but in 2023, the board decided to drop its nonprofit status. Since then, it has operated as a volunteer-only organization. The board members at the time of the switch realized that what the association was best at was putting on the annual conference and creating books from the content, Cooper-White said. They wanted to make the annual conferences their focus, rather than collecting members and dues.

One of IASC’s books is “What Is Spiritual Care?” in which contributors in various caregiving professions, religious traditions and cultural contexts offered their answer to the question. “The cumulative impact of this work emphasizes that spiritual care is inseparable from larger efforts towards justice and peacemaking,” IASC said of the book on its website.

The Rev. Cynthia Linder, from left, leads a panel discussion on the book, “What Is Spiritual Care?” with Rabbi Mychal Springer, the Rev. Pamela Cooper-White, Daniel Schipani, president of IASC, and Mahmoud Abdallah, Tuesday, July 22, 2025, in Chicago. (Photo by Rachel Berkebile)

Members of the IASC board, including its president, Daniel Schipani, and contributors to the book spoke about the question on a panel, discussing the importance of and challenges around their attempts to maintain a broad, international and interfaith definition of spiritual care.

Each speaker on the panel offered their definition of spiritual care. Rabbi Mychal Springer, who founded the Center for Pastoral Education at Jewish Theological Seminary in New York City, said spiritual care is the “work of sustaining people in the spirit.”

Schipani’s definition included spiritual care as “a compassionate response to human suffering.” While Mahmoud Abdallah, an academic staff member at the Center for Islamic Theology at the University of Tübingen in Germany, said the field of spiritual care “is still open to design.” The panelists seemed to agree on the importance of community in doing the work of pastoral care and that it is not work that can be done alone.

No comments:

Post a Comment