Mélissa Godin TIME

Fri, February 19, 2021

Extinction Rebellion Climate Crime Invesigators

Police watch as Extinction Rebellion "crime scene investigators" in white suits and masks put up climate crime scene tape to investigate areas of ecocide in a performance outside the Brazilian Embassy on Sept. 7, 2020 in London, United Kingdom Credit - Mike Kemp—In Pictures, via Getty Images

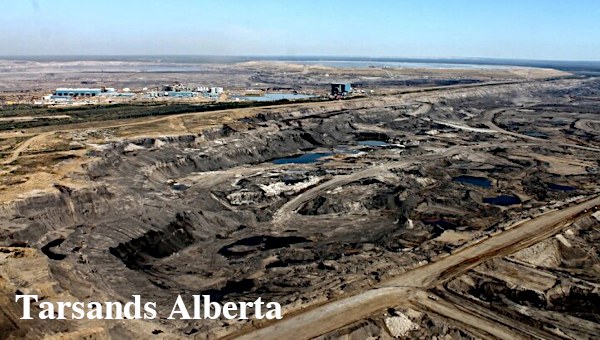

When a Nigerian judge ruled in 2005 that Shell’s practice of gas flaring in the Niger Delta was a violation of citizens’ constitutional rights to life and dignity, Nnummo Bassey, a local environmental activist, was thrilled.

Bassey’s organization, Friends of the Earth, had helped communities in the Niger Delta sue Shell for gas flaring, a highly polluting practice that caused mass disruption to communities in the region, polluting water and crops. Researchers had found that those disruptions were associated with increased rates of cancer, blood disorders, skin diseases, acid rain, and birth defects—leading to a life expectancy of 41 in the region, 13 years fewer than the national average.

“For the first time, a court of competence has boldly declared that Shell, Chevron and the other oil corporations have been engaged in illegal activities here for decades,” Bassey said on Nov. 14, 2005, the day the Federal High Court of Nigeria announced the ruling. “We expect this judgement to be respected and that for once the oil corporations will accept the truth and bring their sinful flaring activities to a halt.”

Yet the judgement was not respected. A United Nations report published six years later found that Shell had not followed its own procedures regarding the maintenance of oilfield infrastructure. Today, Shell is still gas flaring in the Niger Delta.

In the 15 years since the ruling, Bassey has come to believe that Shell’s executives might have been held accountable had the case gone to the International Criminal Court (ICC). “Shell could ignore [the case] because it wasn’t in the international media but if it had gone to the ICC, it would have gotten global attention and shareholders would have known what the company was doing,” he says. “If we had had an ecocide law, things would have turned out differently.”

The word “ecocide” is an umbrella term for all forms of environmental destruction from deforestation to greenhouse gas emissions. Since the 1970s, environmental advocates have championed the idea of creating an international ecocide law that would be adjudicated in the ICC and would penalize individuals responsible for environmental destruction. But the effort has gained significant traction over the past year, with leaders from Vanuatu, the Maldives, France, Belgium, the Netherlands—as well as influential global figures like Pope Francis and Greta Thunberg—expressing their support. Although there are questions about whether the ICC as an institution has the teeth to prosecute any crimes, Bassey and other activists believe the law will act as a powerful deterrent against future forms of environmental destruction. “We will not get different outcomes in cases of exploitation and marginalisation unless we reimagine the laws that govern us,” Bassey says.

In December 2020, lawyers from around the world gathered to begin drafting a legal definition of ecocide. If they succeed, it would potentially situate environmental destruction in the same legal category as war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity. But even within the movement, questions remain on how far the law should go — and who might fall under its jurisdiction.

The history of the ecocide movement

The term ecocide first rose to the public consciousness in 1972, when Olof Palme, the premier of Sweden, used the term at a United Nations environmental conference in Stockholm to describe the environmental damage caused by the Vietnam War. At the conference, an ecocide convention was proposed but never came to pass.

The idea resurfaced again in the 1990s when the ICC, the world’s first permanent international criminal court, was being created. As a court of last resort, the ICC was established not to override national courts but to complement them, creating a global tribunal that would adjudicate the gravest crimes of concern to the international community. When lawyers came together in 1998 to draft the Rome Statute, the founding document of the ICC, there was a law in the pipeline that would have criminalized environmental destruction.

But the law never came about. “My recollection is that there was just no political support for it,” says Philippe Sands, who was involved in drafting the preamble of the Rome Statute in 1998 (and who would go on to co-chair the expert panel formed in 2020 to draft a legal definition of ecocide). Environmental destruction, Sands says, was not on the public’s consciousness.

This began to change in 2017 when Polly Higgins, a British barrister, launched the Stop Ecocide campaign alongside environmental activist Jojo Mehta. Higgins, who sold her home in 2010 to raise funds to combat environmental destruction, wrote an influential book, Eradicating Ecocide, that informed the legal debate. When the campaign launched a few years later, it quickly gained unprecedented momentum: Greta Thunberg donated €100,000 of the money she received from that year’s Gulbenkian Prize for Humanity to the cause, and for the first time in history, several world leaders publicly backed the idea. Fast-forward three years and now, an expert panel of international criminal lawyers is drafting a definition of ecocide. “Six months ago, we never would have believed where we are at now,” says Mehta. Higgins, sadly, never lived to see her campaign bear fruit, dying in 2019 at the age of 50.

Environmental advocates believe an ecocide law at the ICC would be groundbreaking. While some countries have national laws on environmental harm, there is no international criminal law that explicitly imposes penalties on individuals responsible for environmental destruction. If adopted, experts say there are three main areas where an ecocide law would make a difference.

The first is the symbolic impact of having the ICC elevate environmental destruction to the same level as genocidal crimes. Mehta argues that the fear of being labelled an ecocide criminal could create incentives for leaders to behave more responsibly. “A CEO doesn’t want to be seen in the same bracket as a genocidal maniac,” she says.

The second area where this law could make a difference is by setting a legal precedent, creating a bandwagon effect where international law could prompt changes in national criminal laws, as countries look to signal their environmental commitment to others. ICC laws have influenced national policies before: several countries, including Germany and the Netherlands, have adopted national laws that criminalize ICC crimes.

The third way an ecocide law could be useful is by prosecuting environmental crimes that fall outside of national jurisdictions. This is especially helpful in poorer countries where legal barriers make it difficult to hold foreign companies accountable. An ecocide law, Bassey says, would create an arena in which marginalized communities in countries like Nigeria have a voice against powerful, polluting actors. “Most of this ecocide devastation is happening in communities where voices are not heard,” he says.

A picture taken on March 22, 2013 shows gas flare at Shell

Advocates of an ecocide law also believe it would change the way the environment is valued. “There is something powerfully urgent about the idea that nature has rights,” says Mitch Anderson, founder and executive director of Amazon Frontlines, an organization that works with Indigenous communities in the Western Amazon to protect their lands. “The [ecocide] law would ensure that nature has a legal voice.”

There’s still a long way to go, though. While lawyers are expected to finish a draft of the law by the end of spring, it will take at least 3 to 5 years before the law might be ratified. Drafting the law is just the first of many steps: a member state needs to propose it to the ICC, at which point, 50% of ICC states have to approve it. States will then need to convene to debate the exact definition of the law before eventually, adopting and ratifying it.

But if passed, an ecocide law would be unique in the ICC’s history, not only because of what it would protect but who it could go after—the heads of countries and corporations that are big polluters. Historically, the ICC has been criticized for targeting only African dictators while turning a blind eye to Western leaders responsible for mass atrocities. But with an ecocide law, powerful white men—who are often disproportionately represented in extractive industries—could face criminal charges. “The ecocide movement is powerful not only in the legal precedent it could set for protecting rivers, forests, oceans and the air but also in the names and faces it identifies as being behind this destruction,” says Anderson. “[They] may not look like the picture we’re used to seeing.”

Oil and gas companies contacted by TIME did not want to comment on whether they support an ecocide law, but the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (IOGP) said in a statement they “want to further improve the environmental performance and reduce the likelihood and consequences of incident.”

What counts as ecocide?

Bassey is confident that many of the world’s worst environmental offenses —such as Chevron’s pollution of the Ecuadorian Amazon in the 1990s or the ongoing coal-seam fires in Witbank, South Africa—could have been prevented had an ecocide law been in place. “If we had an ecocide law, no one would allow this to go on,” he says. In theory, that might be true. But in practice, much depends on how the term is defined.

Sands, the co-chair of the panel drafting the law, is concerned that the bar for what counts as “ecocide” could be set too high. There’s historical precedence for such a scenario: When the idea of “genocide” was first proposed in 1944 by Raphael Lemkin, a Polish lawyer, he envisioned a law that would prosecute individuals that killed members of a national, ethnic, racial, religious or political group. But when member states—many of whom who were worried about their own histories of discrimination—came together to actually draft the law in 1948, they decided that lawyers needed to prove not only that an individual killed members of a group but that they did so with the specific intention to kill.

The result is that most genocide trials heard by the ICC have not ended with a guilty verdict because the burden of proof is too high. Sands is worried the same mistake might be made with the definition of ecocide. “It will never be possible to prove that someone intended to destroy the environment on a massive scale,” he says. “If we set the bar too high, we won’t catch anyone.”

On the other hand, if the bar is set too low—if the ecocide law encompasses too many types of alleged environmentally destructive acts, and implicates too many types of people and institutions—it may lose political support. Many people might get behind an ecocide law that charges mega-corporations for polluting on a grand scale; it is less likely they would support a law that penalizes anyone who destroys the environment in any way. The lawyers drafting the definition didn’t want to offer their opinion on what, specifically, a “low bar” would look like out of concern that doing so would put at risk their ability to advocate for a more robust law.

But even if a robust ecocide law is put in place, the movement faces another big challenge: the limited legal powers of the ICC. On its own, the ICC does not have the authority to enforce laws; it is completely reliant on its member states to arrest and surrender the accused. If a country does not comply—if it does not arrest the accused individual—there is no trial. In addition, over 70 countries are not members—including the United States. Some of the biggest fossil fuel corporations, such as Exxon Mobil and Chevron, are American owned, meaning they would be unlikely to be drawn into a prosecution.

Lawyers working on the ecocide law are acutely aware of these limitations. “Let’s not be starry eyed about our legal international frameworks at the international level,” Sands says. “Let’s be realistic.” Holding perpetrators of environmental destruction to account, he says, must ultimately be done at the national level. Nevertheless, international criminal law can be a tool that catalyzes thinking and helps set a precedent. Although only four people have been convicted at the ICC since it began hearing cases in 2002, the creation of ICC law has influenced national policy through the norms and precedents it helped to generate. Advocates of ecocide believe the law could do something similar.

“We know one law won’t change everything,” says Mehta. “But without something like this in place, it’s hard to see how these [environmental] targets will be met.”