Imperialism is not the creation of any one or of any group of states. It is the product of a particular stage of ripeness in the world development of capital, an innately international condition, an indivisible whole, that is recognizable only in all its relations, and from which no nation can hold aloof at will…

— Rosa Luxemburg, The Crisis of German Social Democracy (1916)

The arguments embroiling the left on the nature of imperialism, over whether Peoples’ China or Russia is capitalist or imperialist, whether the pink tide in Latin America is a socialist trend, whether the BRICS development is an anti-imperialist movement, and so forth, are becoming more and more heated as they proceed further and further into the academic weeds.

There is a host of issues and positions entangled in these debates, as well as numerous vested interests: deeply felt, long held theories, research platforms, and networks of intellectual allies.

Moreover, these arguments are decidedly one-sided: long on academic opinion, short on working-class or activist participation.

That said, they are important and deserve discussion.

A recent interview of Steve Ellner by Federico Fuentes in LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal is a place to begin to unravel some of these disputes. Now Steve Ellner is neither a surrogate in nor a straw man for this discussion. Ellner is a thoughtful, analytical academic with a long-committed history in the Latin American solidarity movement and with a background on the left. He is more likely to say “X may mean…” rather than “X must mean…” than many of his academic colleagues. That is to say, he is no enemy of nuance.

Ellner begins with Lenin, as he should, and asserts that Lenin’s theory is both “political-military” and “economic.” This, of course, is correct. In Chapter seven of Imperialism, Lenin specifies five characteristics of the imperialist system. Four are economic: the decisive role of monopoly capital, the merging of financial and industrial capital, the export of capital, and the internationalization of monopoly capital. One is political-military: the division of the world between the greatest capitalist powers.

Lenin gives no weight to these characteristics because they are together necessary and sufficient for defining imperialism as a system emerging in the late nineteenth century. Imperialism, for Lenin, is a stage and not a club.

Following John Bellamy Foster, the editor of Monthly Review, Ellner posits that there are two interpretations of imperialism that some believe follow from the two aspects of imperialism. Indeed, there may well be two interpretations, but given Lenin’s unitary interpretation of imperialism in Chapter seven, they are misinterpretations of Lenin’s thought. Recognizing that Lenin explicitly says that he offers a definition “that will embrace the following five essential features…,” there is, perhaps to the dismay of some, only one valid interpretation– an interpretation that combines the economic with the political-military.

That said, Foster and Ellner are correct in critically appraising those who do misinterpret imperialism as solely political-military (contestation of territories among great powers) or as solely economic (capitalist exploitation). Truly, most of the misunderstandings about imperialism since Lenin’s time come from advocating one misinterpretation rather than the other, while failing to perceive imperialism as a system.

Ellner gently rejects one political-military interpretation that he associates with Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin: equating “imperialism with the political domination of the US empire, backed of course by military power…” Ellner rejects that thesis, “given declining US prestige and global economic instability.” An interpretation that separates and privileges the political-military from the economic necessarily decouples imperialism from capitalism — something that Lenin explicitly denies. Accordingly, it follows that modern-day imperialism — including US imperialism — would be akin to the adventures of Alexander the Great or Genghis Khan, leaving exploitation as, at best, a contingent feature.

A solely political-military explanation of imperialism is a step removed from the more robust Leninist explanation.

Ellner considers the economic interpretation: “At the other extreme are those left theorists who focus on the dominance of global capital and minimize the importance of the nation-state.” Ellner has in mind as his immediate target the position staked out by William I Robinson, Jerry Harris, and others in the late 1990s, a position that rides the then-dramatic wave of globalization to posit a supremely powerful Transnational Capitalist Class (TCC) that overshadows, even renders obsolete, the nation-state.

At the time, others pointed out that the substantial quantitative changes in trade and investment and their global sweep had been seen before and were simply a repeat of the past, most telling in the decades before the first world war. Were these changes not a continuation of the qualitative changes addressed in Lenin’s Imperialism?

Like many speculations that overshoot the evidence, the projected decline or death of the nation-state was made irrelevant by the march of history. The many endless and expanding wars of the twenty-first century underscored the vitality of the nation-state as an historical actor. And the intense economic nationalism spawned by the economic crises of recent decades signals the demise of globalization — a phenomenon that proved to be a phase and not a new stage of capitalism. Sanctions and tariffs are the mark of robust, aggressive nation-states.

The tempest in an academic teapot stirred by the artificial separation of the economic and the political-military in Lenin’s theory of imperialism is enabled by lack of clarity about the nature of the state. Left thinkers, especially in the Anglophone world, have neglected or derided the Leninist concept of State-Monopoly Capitalism — the process of fusion between the state and the influence and interests of monopoly capitalism — which explains exactly how and why the nation-state functions today in the energy wars between Russia and the US and the technology wars between Peoples’ China (e.g., Huawei) and the US. Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran’s casual dismissal of the concept of State-Monopoly Capitalism in Monopoly Capital (1966) is representative of the utter contempt shown for Communist research projects by many so-called “Western Marxists.” While the theory of State-Monopoly Capitalism gets no hearing among Marxist academics, the slippery, but ominous-sounding concept of “deep state” has achieved wide-spread acceptance, while not taxing the comfort of Western intellectuals.

Nonetheless, Robinson’s stress on the political economy of imperialism cannot easily be dismissed. His reliance on the key concepts of class and exploitation are certainly essential to Lenin’s theory.

In fact, the greatest challenge to the political-military aspect of Lenin’s theory was not the alleged decline of the nation-state, but the demise of the colonial system, especially with the wide-spread independence movements after World War II. The crude and totalizing domination of weaker nations favored by the Spanish, French, Portuguese, and British Empires– the division of the world into administered colonies– was, with nominal independence, replaced by a system of more benign economic domination. Kwame Nkrumah, the Ghanaian revolutionary, designated this system “neo-colonialism” in his book, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. Nkrumah’s elaboration of Lenin’s theory preserved the integrity of Lenin’s “political-military” aspect by reconstituting the colonial division of the world by the great powers into a neo-colonial division of the world into spheres of interest and of prevailing economic influence.

Since Ellner correctly acknowledges that Lenin’s economic and political-military aspects are essential to his theory of imperialism, he must contend with an awkward, vexing question that continually divides the left: how does the People’s Republic of China (PRC) fit into the world imperialist system? What does its deep and broad participation in the global market mean?

Ellner appeals to the facts that the PRC does not have bases throughout the world, does not use sanctions (not true!), and does not exploit the excuse of human rights to intervene in the affairs of other countries.

But surely this side steps Nkrumah’s powerful thesis that imperialism in the post-World War II era is not simply the vulgar exercise of administrative and military power and the exhibition of national chauvinism. It is, rather, the division of the world into spheres of interest that both benefit the great powers through exploitation and the competition with other great powers for shares of the bounty.

Certainly, the PRC does not avow a policy of imperial predation, but neither does the US or any other great power from the past. Indeed, imperialism has always been presented — sincerely or not — as beneficial to all parties, whether it is a civilizing function, a paternalistic boost, or protection from other powers. The Chinese leadership may well truthfully believe that their trade, investment, and partnership with other countries is a victory for all — a “win-win” as some like to say.

But that is always the answer that great powers give that are using their capital, their know-how, and their trade to profit their corporations. Perhaps, the most notorious of these “win-win” projects was the Marshall Plan. Sold to Europe as a “win-win” based on Europe’s impoverishment and the US’s generosity, billions were allocated for loans, grants, and investments in Europe. History shows that billions in new business for US corporations were thus created, Cold War political dependency and loyalty were achieved, and the US retained new markets for decades. The big winners, of course, were US corporations and their capital-starved European counterparts.

Other US investment and “aid” projects, like The Alliance for Progress, were more blatantly guided by US interests and even less a “win” for their targets.

This was the era of the development theories of W.W. Rostow that offered a blueprint and a justification for the investment of capital in and the corporate penetration of poorer countries. It was, in fact, a justification for neo-colonialism. Yet Rostow’s stage theory of lifting countries from poverty can appear surprisingly consonant with the logic of the PRC’s foreign investment strategies.

It is hard to resist the temptation to ask: How is this different from the PRC Belt and Road Initiative? How is the BRI different from the Marshall Plan? Or, to use an example from Lenin’s time, the Berlin-Baghdad railroad project?

It is beyond dispute that Peoples’ China — whatever the goals of its ruling Communist Party — has a massive capitalist sector, with many corporations arguably of monopoly concentration rivaling their US and European counterparts, that similarly seek investment opportunities for their accumulated capital. That is, after all, the motion of capitalism.

What is baffling and frustrating for those sympathetic to the Communist Party of China is the failure for the CPC’s leaders to frame their economic policies towards other states in the language of class or employ the concept of exploitation. In Comrade Xi’s recent speeches at the Kazan meeting of BRICS+, there are many references to “multilateralism,” “equitable global development,” “security,” “cooperation,” “advancing global governance reform,” “innovation,” “green development,” “harmonious coexistence,” “common prosperity,” and “modernization,” — all ideas that would resonate with the audience of the G7. How would these values change the class relations of the BRICS+ nations? What does this thinking do to alleviate the exploitation of capitalist corporations?

These are the questions Ellner and others should be asking of the PRC’s leaders and the advocates of BRICS+. These are the questions that probe how today’s nation-states participate in the imperialist system and how that participation affects working people.

The problem is that many on the left would like to believe that there is a form of anti-imperialism that is not anti-capitalist. They find in the BRI and BRICS+ a model that competes with United States imperialism and could be said to be therefore anti-US imperialist, but leaves capitalism intact. Of course, it is impossible to embrace this view and retain Lenin’s theory of imperialism. Every page in the pamphlet, Imperialism, affirms the intimate relation between imperialism and capitalism. The very subtitle — The Final Stage of Capitalism — is testimony to that connection.

Ellner suggests that a political case can be made in the US for singling out US imperialism over imperialism, in general. He wants us to believe, through an example of Bernie Sanders’ strategic thinking, that criticizing US foreign policy is far more threatening to the ruling class than Sanders’ “socialism.” That may be true of Sanders’ tepid social democratic posture, but not of any serious “socialist” stance against capitalism and its international face.

We get a taste of Ellner’s vision of the role of BRICS-style anti-imperialism when he conjectures that “Anti-imperialism is one effective way to drive a wedge between the Democratic Party machine and large sectors of the party who are progressive but vote for Democratic candidates as a lesser of two evils.” Rather than take the failed “lesser-of-two-evils” policy head on, rather than contesting the idea of always voting for candidates who are bad, but maybe not as bad as an opponent, the left might instead wean Democrats away from slavish support for the Democratic Party agenda by standing against US foreign policy (which is largely bipartisan!). If trickery and parlor games count as a left strategy within the Democratic Party orbit, maybe it’s time to leave that orbit and look to building a third party.

Ellner’s interrogator, Federico Fuentes, correctly questions how making US imperialism the immediate target of the Western left might possibly overshadow or even conflict with the class struggle, the fight for socialism. He opines: “There can be a problem when prioritising US imperialism leads to a kind of ‘lesser evil’ politics in which genuine democratic and worker struggles are not just underrated, but directly opposed on the basis that they weaken the struggle against US imperialism…”

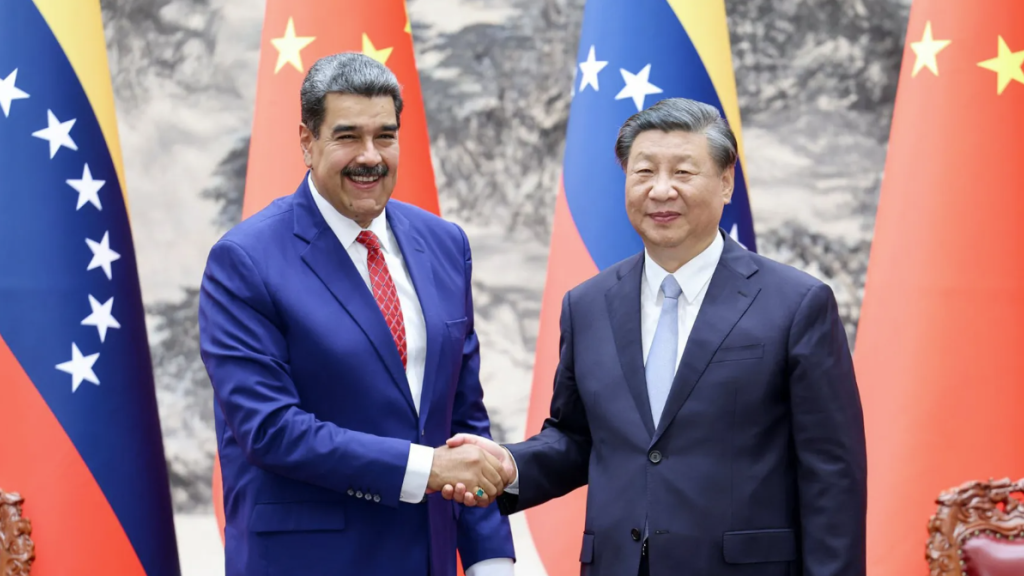

Fuentes and Ellner, in this regard, are fully aware of the recent dispute between the Maduro government and the Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV) over the direction of the Bolivarian process, a dispute that resulted in an attempt to eviscerate the PCV on the part of Maduro’s governing party. Because the PCV was opposing the Maduro party in the July, 2024 election, Maduro maneuvered to have the PCV stripped of its identity, securing an endorsement from a bogus PCV constructed of whole cloth by Venezuelan courts.

From the PCV’s perspective, the Maduro government had abandoned the struggle for socialism in deed, if not word, and turned on the working class, compromising Chavismo in order to hold on to power. As a Leninist party, PCV held fast to the view that there is no anti-imperialism without anti-capitalism. Thus, the government’s reversal of many working-class gains had lost working-class support and, therefore, the support of the PCV.

Some Western leftists uncritically support the Maduro government and deny or ignore the facts of the matter. They are delusional. The facts are indisputable. Ellner is not among those denying them.

Still others argue that defense of the Bolivarian process against the machinations of US imperialism should be an unconditional obligation of all progressive Venezuelans, including the Communists. Therefore, the Communists were wrong to not support the government.

But surely this thinking calls for Venezuelan workers to set aside their interests to serve some bourgeois notion of national sovereignty. It is one thing to defend the interests of the workers against the enslavement or exploitation of a foreign power. It is quite another to defend the bourgeois state and its own exploiters without taking exception.

This was the question that workers and their political parties faced on many occasions in the twentieth century: whether they would rally around a flag of national sovereignty when they essentially had little to gain but a fleeting national pride.

As Lenin, Luxemburg, Liebknecht, and their contemporaries argued during the brutal bloodletting of the First World War, workers should refuse to participate in the “anti-imperialism” of national chauvinism, the clash of capitalist states.

The road to defeating imperial aggression — US or any other — is to win the working class to the fight, with a class-oriented program that attacks the roots of imperialism: capitalism. Unity around the goal of defeating the imperialist enemy — in Russia, China, Vietnam, or anywhere else — was won by siding with workers against capital, not accommodating or compromising with it. That was the message that the Communist Party tried to deliver to the Maduro government.

Restraining, containing, or deflecting US imperialism will not defeat the system of imperialism, anymore than restraining, containing, deflecting, or even overwhelming British imperialism, as occurred in the past, defeated imperialism. Only replacing capitalism with socialism will end imperialism.

That in no way diminishes the day-to-day struggle against US domination. It does, however, mean that the countries participating in the global capitalist market will reinforce the existing imperialist system until they exit capitalism. While there can be an anti-US imperialist coalition among capitalist-based countries, there can be no anti-imperialist coalition made up of countries committed to the capitalist road.

The left must be clear: a multipolar capitalist world has no more chance of escaping the ravages of imperialism than a unipolar capitalist world. If anything, multipolarity multiples and intensifies inter-imperialist rivalry.FacebookRedditEmail