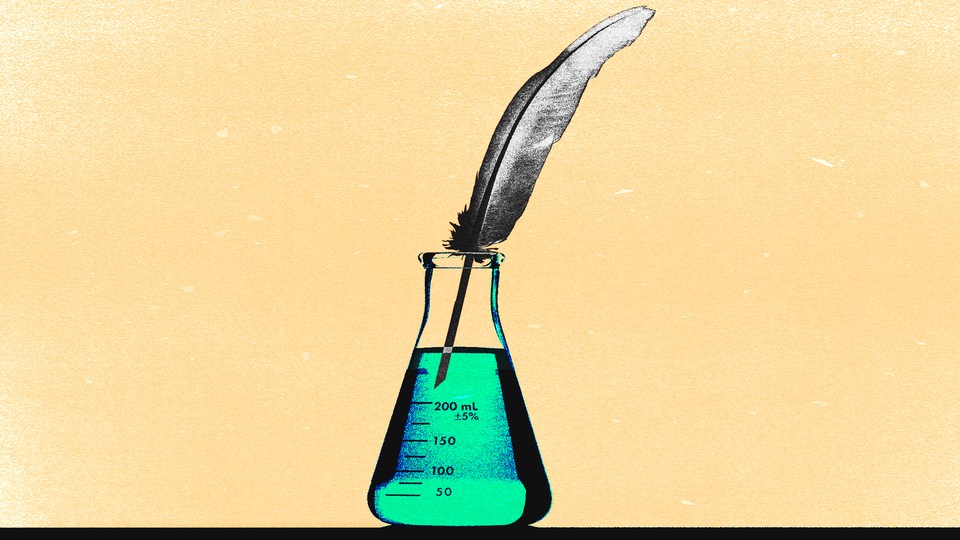

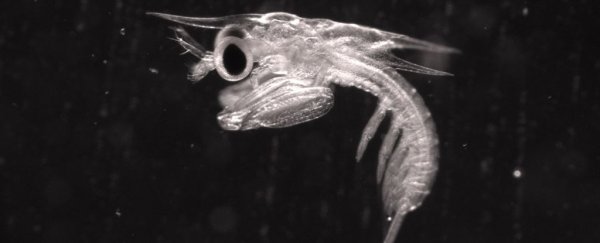

Side view of an 11-day-old mantis shrimp larva. (Jacob Harrison)

NICOLETTA LANESE, LIVESCIENCE

30 APRIL 2021

Mantis shrimp wield a spring-loaded appendage that punches through water with explosive force - and their babies can start swinging just nine days after they hatch.

In a new study, published Thursday (April 29) in the Journal of Experimental Biology, scientists studied larval Philippine mantis shrimp (Gonodactylaceus falcatus) originally collected from Oahu, Hawaii.

The team also reared some of the same species from eggs, carefully monitoring their development through time and then zooming in on their punching appendage under the microscope.

The appendage, called the raptorial appendage, works similarly to a bow and arrow, in that the tip of the appendage gets pulled back, "nocked" against a spring-like mechanism and then let loose in a sudden release of elastic energy, said first author Jacob Harrison, a graduate student in the biology program at Duke University.

"While we have a pretty great understanding of how it functions in the adults … we didn't really have a solid understanding of how it develops," Harrison told Live Science.

Related: Smash! Super-stabby mantis shrimp shows off in video

Now, in a "remarkably complete and carefully controlled" study, Harrison and his team have started to unravel the mystery of when mantis shrimp start throwing down like lightning-fast boxers, said Roy Caldwell, a professor of integrative biology at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the study.

And furthermore, since larval mantis shrimp have transparent shells, "what's new about this study is [that] the transparency of the raptorial apparatus allows them to see in great detail exactly what's going on," Caldwell said.

"That hasn't been possible in looking at adults," whose exoskeleton is opaque, he said.

Slower than expected, but still impressive

When adult mantis shrimp unleash a flurry of strikes, the tips of their appendages can slice through the water at about 50 mph (80 km/h), according to National Geographic.

But a mathematical model, published in 2018 in the journal Science, hinted that baby mantis shrimp might throw even faster punches than adults, assuming they take up boxing at a young age.

This model, developed in the same lab Harrison works in, zoomed in on the spring mechanism mantis shrimp use to deliver punishing blows.

"We see these mechanisms all over biology," from jumping frogs and insects to stinging jellyfish that fire venom-filled capsules into their prey, Harrison noted.

The model hinted that these spring-loaded mechanisms should generally become less efficient at larger scales, and therefore, smaller springs with less mass should generate higher acceleration when let loose.

Another model that specifically focused on mantis shrimp revealed a similar result, indicating that larger mantis shrimp species strike more slowly than smaller species, the researchers reported in 2016 in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Harrison and his team wanted to see if these models held up in larval mantis shrimp, since of course, they're smaller than adults of their species. So the team searched for tiny, translucent mantis shrimp in Hawaii in the dead of night.

"If you go out where you can find adult mantis shrimp, you can actually stick a light in the water, and mantis shrimp will come like a moth to a flame," Harrison said. That said, larval crabs, shrimp and fish also flock to the light and get scooped up in the same buckets as the mantis shrimp; so therein lies the challenge.

These free-swimming shrimp larvae had matured enough to exit the burrow in which they hatched, so they tended to be at least 9 to 14 days old at the time of capture, Harrison noted.

To collect data on even younger mantis shrimp, Harrison also collected an egg clutch from a female G. falcatus found at Wailupe Beach Park. The eggs hatched in transit on their way to Duke University, but the team still managed to raise the puny mantis shrimp for 28 days in their lab.

Related: Six bizarre feeding tactics from the depths of our oceans

With mantis shrimp in hand, the team carefully observed how the larvae developed through time. G. falcatus larvae were previously known to progress through six larval stages, each marked by the larva molting its exoskeleton. The team found that, in the first and second larval stages, the larvae huddled together at the bottom of the tank; by the third stage, they began swimming but did not throw any punches.

But by the fourth stage, around day 9 to 14, "larvae began striking and 'waving' their raptorial appendages as they swam through the water," the authors wrote in their report.

At this point, the raptorial appendages had fully formed and closely resembled an adult's, in terms of structure, and the larvae also began snacking on larval brine shrimp that the team provided. Each larva measured about the size of a grain of rice at this juncture.

The team shot high-speed, high-resolution video of the strikes by the older larval mantis shrimp they'd scooped from the ocean, to see just how they hurl their appendages through water. This required placing the rice-size larvae into a custom rig and securing them with glue, so they'd stay in frame and in focus.

The footage enabled the team to not only examine the speed and mechanics of each punch, but also to watch as elements of the spring mechanism slid to and fro under the transparent exoskeleton.

"What we found was that they could produce really high accelerations and velocities relative to their body size," Harrison said.

These metrics specifically measure how rapidly the larvae appendages can transition from stillness to striking, so in this respect, the larvae were "roughly on par with a lot of the adult species," he said.

However, in terms of their overall speed, the larval strikes only traveled about 0.9 mph (1.4 k/h) - an order of magnitude slower than the adult strikes.

"The finding that was a little bit surprising was that the speed of the strike is less than what we see in adults," Caldwell said.

This difference in speed may be related to the actual materials making up the spring, he said; perhaps the spring itself or the "latch" that nocks the appendage in place, differs in larval and adult mantis shrimp, limiting the amount of elastic energy that the larvae can deploy.

Related: Dangers in the deep: 10 scariest sea creatures

The water surrounding the mantis shrimp may also impact their striking speed, Harrison suggested.

To teeny marine creatures, like larvae, water feels quite viscous, more like molasses than water as we experience it, he said. It may be that, as mantis shrimp mature, they can better overcome the stickiness of the water and execute faster strikes.

And despite being slower than adults, the larvae still threw punches that were five to 10 times faster than the reported swimming speeds of similarly sized organisms and more than 150 times faster than their favorite brine shrimp snacks can swim, the authors wrote.

Evolutionarily, there may not be much pressure for larvae to increase their striking speed before reaching maturity, Caldwell said.

The study is also limited in that the team only collected video of defensive strikes, provoked by irritating the larvae with a toothpick, Caldwell noted. "We know, in adults, there's considerable ability to modulate the strength of the strike depending on what it's being used for," whether that be defense, or capturing or stabbing prey, he said. So the speed of the strike may differ somewhat, depending on its purpose.

Looking forward, Harrison and his team plan to probe what factors limit the larval mantis shrimps' striking speed, as well as when the shrimp overcome this limitation in the course of development, he said. They also want to examine whether the raptorial appendage develops similarly across the hundreds of mantis shrimp species, he added.

"The larval stomatopods," another term for mantis shrimp, "are basically a black box, we know very little about them," Caldwell noted. "Almost anything done on larval stomatopods is new and interesting … They've just literally scratched the surface in terms of looking at morphology."

Related Content:

Image gallery: Magnificent mantis shrimp

Photos: The amazing eyes of the mantis shrimp

Photos: Ancient shrimp-like critter was tiny but fierce

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.