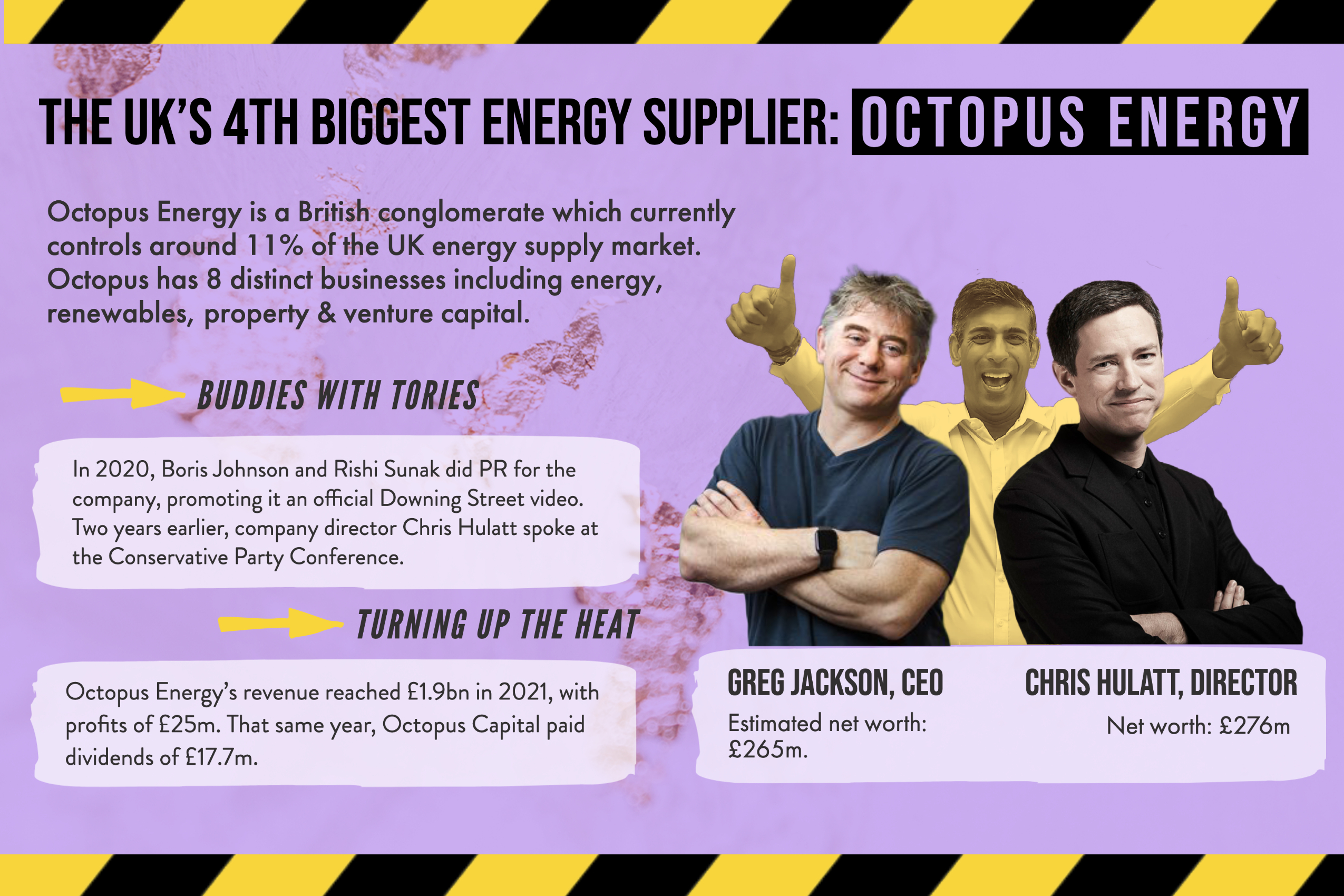

CRISIS CAPITALISM: OCTOPUS ENERGY

INVESTIGATION

28 November 2022

In the third installment of Heat the Rich – an investigative series on energy firms profiting from the cost of living crisis – Corporate Watch takes a critical look at the UK’s fourth-biggest energy supplier, Octopus Energy.

Image description: A remote-controlled light switch is operated on by a nearby smartphone.

Image description: A remote-controlled light switch is operated on by a nearby smartphone.Credit: Green energy futures/Flickr

Octopus Energy Ltd is the fourth biggest energy supplier in the UK currently controlling around 11% of the energy supply market. It is the newest supplier in the big six, trendy enough to be reviewed by Vogue and posed as a ‘solution’ to “a broken, inefficient market”.

Originally launched in the UK in 2016, Octopus Energy Group Ltd now operates in 13 other countries with 23 million customer accounts. Its model is supposedly a “cheap green energy system” funded by “high sums of investment”.

But the Octopus name is not limited to the energy market. In 2018, it was listed as managing over £7 billion in assets with over 50,000 investors, Since then, it’s continued to grow, Octopus now operates eight distinct businesses: Octopus Energy, Octopus Investments, Octopus Healthcare, Octopus Ventures, Octopus Real Estate, Octopus Moneycoach, Octopus Renewables, Seccl and Octopus Wealth.

According to co-founder Christopher Hulatt, the group takes a holistic approach: “by building companies with one purpose – the relentless pursuit of ‘better’.” But better for who? Better for the pockets of Hulatt and wealth investors or for energy customers…Suffice to say, this isn’t covered in the Octopus Energy Ltd podcast on the Energy Crisis.

HOW MANY UK ENERGY CUSTOMERS DOES OCTOPUS ENERGY HAVE?

Electricity (excluding pre-payment): 3.1 million

Gas (excluding pre-payment): 2.7 million

WHO OWNS IT?

Touted as an “independent supplier” by Forbes. Octopus Energy is in fact part of a group, that is ultimately owned by OE Holdco Ltd.

At the start of the tax year in April 2022, OE Holdco Ltd, a UK-based holding company, was owned by the co-founder of Octopus Energy, Christopher Hulatt. But mysteriously, since the end of September OE Holdco Ltd has no listed owner. Hulatt and Octopus co founder Simon Rogers remains two of the three directors of OE Holdco Ltd, the third directorship is held by Octopus Company Secretarial Services Ltd.

OE Holdco Ltd was formed back in March, at the same time as families around the UK were plunged further into the cost of living crisis. Already by September, it has become the ultimate parent company of the Octopus Group. It’s certainly one to keep eye on when annual accounts are due.

It doesn’t seem so, in fact, Octopus Energy appears to be going from strength to strength. According to the company’s accounts from 2021, it recorded record revenues of £1.9 billion in 2021 with profits at £25 million. Bouncing back from a loss of £47 million in 2020.

The Octopus Group, with its fingers in many pies, celebrated a revenue of £2 billion in 2021, £800 million more than in 2020, a 62% increase.

Whilst the ultimate parent company OE Holdco Ltd is too new to file accounts, the Octopus Capital Ltd’s accounts for 2021 show that energy supply is the key moneymaker for the group, accounting for 85% of the total turnover. The group is also expanding internationally through acquisitions in Japan and the USA. The cherry on the cake is that the Group paid dividends of £17.7 million in 2021 in comparison to £3 million in 2020 highlighting that right now business is booming for the Octopus Group, despite the ongoing cost of living crisis.

WHO RUNS IT?

Legend has it that Octopus was started in Chris Hulatt’s bedroom, when Hulatt, Simon Rogerson, and Guy Myles founded the company in 2000. Hulatt and Rogerson remain at the top, while Myles left in 2014 to set up a financial investment company.

Day to day, Hulatt specialises in two things: hunting for investments for Octopus worldwide and cosying up to the UK government through meetings with politicians and ministers. A Cambridge graduate, Hulatt owns over 75% shares of Octopus Group Holdings Ltd and is the director of 30 companies on Companies House including Octopus Energy Ltd. With no official position apart from ‘co-founder’ Hulatt’s salary from Octopus businesses is difficult to measure. But what remains certain, is that Hulatt is not feeling the bite from the energy crisis: with a net worth of £276 million. Outside of the Octopus business, Hulatt is the Chairperson of Enthuse, a digital donation tech company, and the non-executive director of ClearlySo an investment bank.

Simon Rogerson is the chairperson of Octopus Investments, the CEO of both the Octopus Group and OE Holdco Ltd. He is listed as the director of 26 companies and was educated at the University of St Andrews. Rogerson is likely to have taken home at least £663,000 in 2021 as the highest-paid director of Octopus Capital Ltd. But Rogerson’s pockets go a lot deeper than one remuneration. According to business information databases, Rogerson owns 11% of shares at his workplace, making him the biggest single shareholder of the Octopus Group. Rogerson’s net worth is as high as £229 million.

Greg Jackson is the CEO and founder of Octopus Energy Group. Jackson is likely to be earning a salary upward of £169,000 as the highest-paid director of Octopus Energy Group Ltd. Celebrated in iNews, Jackson was seen as a bit of an angel after he gave up £150,000 in autumn 2021 “when the energy crisis began to bite”. But despite a relatively low salary he’s well-placed to make such a “selfless act” because Jackson’s 6% stake in the renewables branch of Octopus means he’s estimated to be worth around $300 million (over £265m).

Aside from Octopus, Jackson is the chairperson of Consultant Connect UK, a private tech business profiting from NHS privatisation through referral management.

THE OCTOPUS ADD-ON? KRAKEN TECHNOLOGY

In addition to cashing in on supplying energy, the Octopus Energy Group has another trick up its sleeve: Kraken Technology – which is part of the Octopus Energy Group

Kraken Technology provides data services to manage energy usage. Kraken’s platform manages “billing, payments, meter data management, CRM, customer communications, digital self-service, contact centre telephony, industry and market connections (and more)”. It appears that through Kraken Technology services Octopus has made a name for itself in the playground of the Big Six, even convincing its competitors like EDF and e.on to buy up its license. Now, 40% of the British market is licensed to Kraken.

DOES THE COMPANY AVOID PAYING TAXES?

Octopus Energy seems to be in the clear. But it’s one to look out for, as OE Holdco is yet to publish its first set of accounts, and has no publicly registered owner.

Moreover, the majority of companies owned by Octopus Investments Ltd are registered as LLPs, which fall under a different tax system in that the LLP itself is not taxable, untaxed profits are distributed to members who then pay tax through a self-assessment tax return.

The Octopus Group certainly doesn’t shy away from speaking about business tax to the government. In May 2022, Octopus Group attended a meeting on business taxation at the HM Treasury with Lucy Frazer MP alongside Uber and BP amongst others.

In 2018 Octopus Investments Ltd donated £12,500 to the central Conservative party. Co-founder, Christopher Hulatt, donated a further £2,500 to the party’s local branch Hitchin & Harpenden (Hulatt’s home constituency) in 2019.

Hulatt’s donation fuelled controversy after Open Democracy revealed it had preceded former chancellor – and now Prime Minister – Rishi Sunak’s, selection of Octopus Investments to manage the government’s £100m “sustainable infrastructure fund”, the UK Infrastructure Bank (UKIB).

DOES THE COMPANY HAVE CLOSE RELATIONSHIPS WITH THE GOVERNMENT?

Yes. As Octopus co-founder Christopher Hulatt put it: “I spend most of my time focusing on…maintaining strong relationships with the UK government and MPs”.

In October 2020, Rishi Sunak alongside Boris Johnson appear to have done PR for Octopus Energy, promoting the company in an official 10 Downing Street video at the Octopus Energy HQ. Between 2020-2022 Octopus had four meetings with former UK prime minister Boris Johnson. This included one solo meeting to discuss energy technology and sustainability in October 2020 as well as a further 125 meetings with ministers to discuss energy: retail, innovation, efficiency and security.

In 2018, Hulatt spoke at the Conservative party conference as part of an event on ‘Boosting Consumer Capitalism’ organised by the right-wing Adam Smith Institute. Fellow speakers included Hulatt’s local Conservative MP, Bim Afolami, and Conservative MP John Penrose.

In 2020, Hulatt was part of the Unlock Britain Commission set up by the aforementioned Bim Afolami to produce a report for the Social Market Foundation to design “10 transformative policies for Britain after the Coronavirus crisis”. Other advisors included top figures from ASOS Plc and PwC.

In 2021, Hulatt led a training on “How to build a nation of entrepreneurs” with Conservative MP and Minister of State for Local Government and Building Safety, Paul Scully as part of The Entrepreneurs Network (TEN).

Last but by no means least, at the end of September when Octopus changed things up, Stuart Quickenden was brought on board as a director for the Octopus Group. Quickenden was a board member for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) between 2017 to 2020. So no doubt he will have some useful contacts to make Octopus Energy’s relationship with government even cosier.

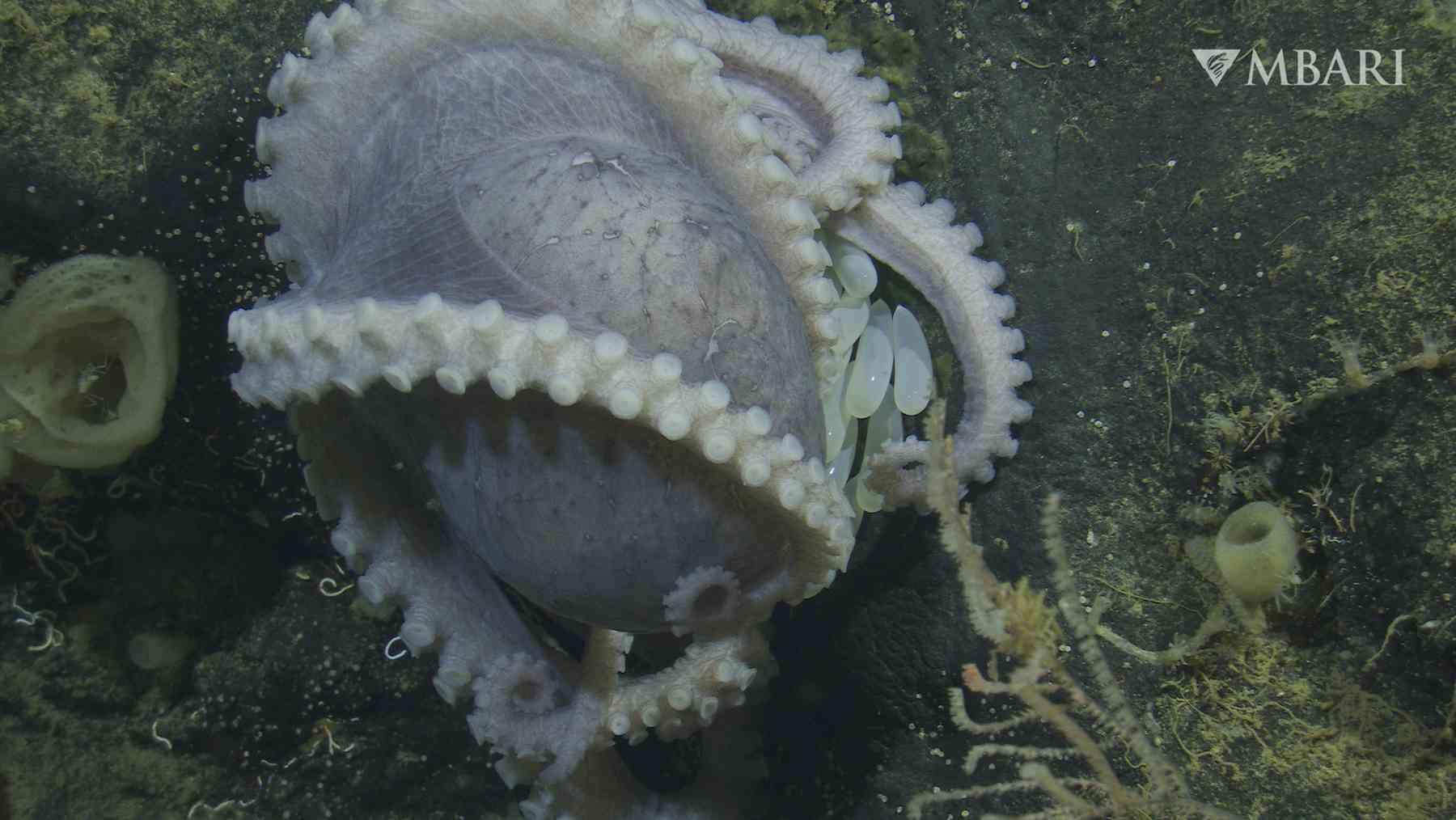

The Octopus Garden is about 2 miles deep near Davidson Seamount, an inactive volcano off the Central California coast. It is inside the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Illustration by Madeline Go/MBARI, basemap created via ArcGIS Online, sources: Esri, USGS | Esri, GEBCO, DeLorme, NaturalVue | California State Parks, Esri, HERE, Garmin, SafeGraph, FAO, METI/NASA, USGS, Bureau of Land Management, EPA, NPS

The Octopus Garden is about 2 miles deep near Davidson Seamount, an inactive volcano off the Central California coast. It is inside the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Illustration by Madeline Go/MBARI, basemap created via ArcGIS Online, sources: Esri, USGS | Esri, GEBCO, DeLorme, NaturalVue | California State Parks, Esri, HERE, Garmin, SafeGraph, FAO, METI/NASA, USGS, Bureau of Land Management, EPA, NPS A female pearl octopus brooding her eggs at the Octopus Garden. Credit: © 2020 MBARI

A female pearl octopus brooding her eggs at the Octopus Garden. Credit: © 2020 MBARI A portion of a photomosaic produced following surveys of the Octopus Garden with MBARI’s remotely operated vehicle Doc Ricketts and the Low-Altitude Survey System sensor suite from the Seafloor Mapping Lab at Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, or MBARI. The photo allowed researchers to count nests and estimate the total. Credit: © 2022 MBARI

A portion of a photomosaic produced following surveys of the Octopus Garden with MBARI’s remotely operated vehicle Doc Ricketts and the Low-Altitude Survey System sensor suite from the Seafloor Mapping Lab at Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, or MBARI. The photo allowed researchers to count nests and estimate the total. Credit: © 2022 MBARI Each octopus has distinctive markings that scientists quickly learned to identify. Credit: © 2022 MBARI

Each octopus has distinctive markings that scientists quickly learned to identify. Credit: © 2022 MBARI A male octopus walks through the Octopus Garden. Credit: © 2019 MBARI

A male octopus walks through the Octopus Garden. Credit: © 2019 MBARI