Long neck helped reptile hunt underwater

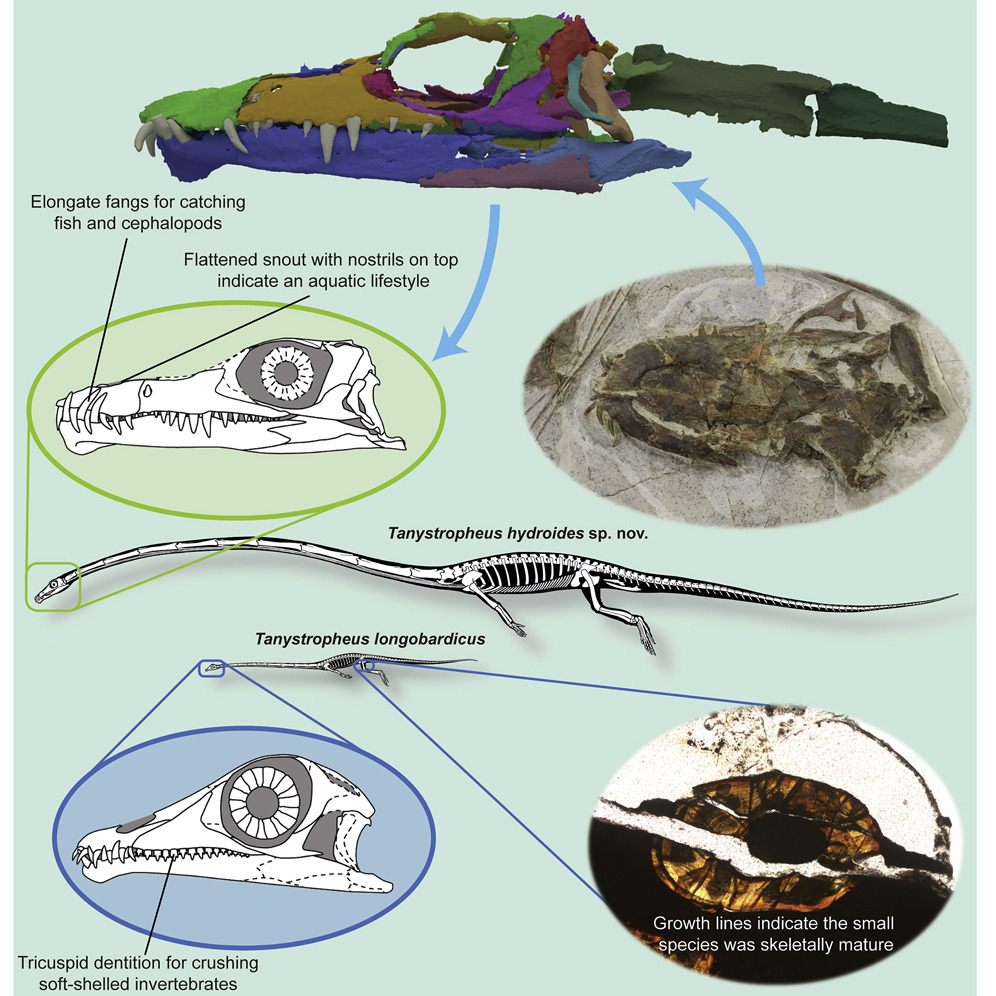

IMAGE: NOSTRILS LOCATED ON THE TOP OF THE SNOUT AND CURVED TEETH, PERFECTLY ADAPTED FOR CATCHING SLIPPERY PREY: THE SKULL OF TANYSTROPHEUS HAS SEVERAL CLEAR ADAPTATIONS FOR LIFE IN WATER. view more

CREDIT: EMMA FINLEY-JACOB

Its neck was three times as long as its torso, but had only 13 extremely elongated vertebrae: Tanystropheus, a bizarre giraffe-necked reptile which lived 242 million years ago, is a paleontological absurdity. A new study led by the University of Zurich has now shown that the creature lived in water and was surprisingly adaptable.

For over 150 years, paleontologists have puzzled over Tanystropheus, its strangely long neck and whether it lived mostly underwater or on land. An international team led by the University of Zurich has now reconstructed its skull in unprecedented detail using synchrotron radiation micro-computed tomography (SRμCT), an extremely powerful form of CT scanning. In addition to revealing crucial aspects of its lifestyle, this also shows that Tanystropheus had evolved into two different species.

Underwater ambush predator

The researchers were able to reconstruct an almost complete 3D skull from a severely crushed fossil. The reconstruction reveals that the skull of Tanystropheus has several very clear adaptations for life in water. The nostrils are located on the top of the snout, much like in modern crocodilians, and the teeth are long and curved, perfectly adapted for catching slippery prey like fish and squid. However, the lack of visible adaptations for swimming in the limbs and tail also means that Tanystropheus was not a particularly efficient swimmer. "It likely hunted by stealthily approaching its prey in murky water using its small head and very long neck to remain hidden," says lead author and UZH paleontologist Stephan Spiekman.

Two species living together

Tanystropheus remains have mainly been found at Monte San Giorgio on the border between Switzerland and Italy, a place so unique for its Triassic fossils that it has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Two types of Tanystropheus fossils are known from this location, one small and one large. Until now, these were believed to be the juveniles and adults of the same species.

However, the current study disproves this assumption. The reconstructed skull, belonging to a large specimen, is very different from the already known smaller skulls, particularly when it comes to its dentition. In order to see whether the small fossils actually belonged to young animals, the researchers looked at cross sections of limb bones from the smaller type of Tanystropheus. They found many growth rings which form when bone growth is drastically slowed down. "The number and distribution of the growth rings tells us that these smaller types were not young animals, as previously considered, but mature ones," says last author Torsten Scheyer. "This means that the small fossils belonged to a separate, smaller species of Tanystropheus."

Specialists in different food sources

According to Spiekman, these two closely related species had evolved to use different food sources in the same environment: "The small species likely fed on small shelled animals, like shrimp, in contrast to the large species which ate fish and squid." For the researchers, this is a really remarkable finding: "We expected the bizarre neck of Tanystropheus to be specialized for a single task, like the neck of a giraffe. But actually, it allowed for several lifestyles."

Reconstructions of the skeletons of Tanystropheus hydroides (large species, newly named) and Tanystropheus longobardicus (small species). The outline of a 170 cm tall diver serves as the scale.###

No comments:

Post a Comment