"It’s a travesty of justice...When the FBI came to me in 1987 and 1988, they threatened me if I didn’t cooperate with them."

Author of the article: Ian Mulgrew

Publishing date :Jan 12, 2022 •

Publishing date :Jan 12, 2022 •

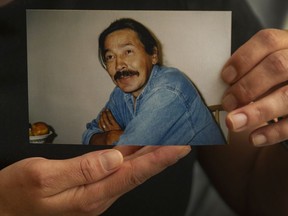

Naneek Graham with a photo of her father John in Vancouver Jan. 11, 2022. B.C. resident John Graham is appealing his extradition to the United States. Graham, a former Yukoner who lived in Vancouver, is accused of killing Anna Mae Pictou-Aquash,a Mi'kmaq activist from Nova Scotia,in 1975 during protests in South Dakota.

PHOTO BY ARLEN REDEKOP /PNG

Article content

John Graham sees himself as little different than the 19th century Ghost Dancers blamed for the original massacre at Wounded Knee — a scapegoat, only this time for the violent American Indian Movement and the 1973 standoff at the iconic Indigenous site.

Extradited more than a decade ago and later convicted in the blood-soaked South Dakota Badlands execution of Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, a 30-year-old Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq woman, Graham maintains his innocence.

Ottawa admitted in the B.C. Court of Appeal this week the now 67-year-old was robbed of procedural fairness by a previous Conservative justice minister in 2010 who amended the original extradition order via a waiver without telling him.

In a brief interview Wednesday from the South Dakota State Penitentiary in Sioux Falls, Graham said he hadn’t been able to watch the two-day Zoom hearing.

He spoke of it giving him hope but exhaled with bitterness:

“I’ve been incarcerated since 2007. I’ve been fighting this case since my U.S. federal indictment in 2003. …They always knew they came to Canada with a defective indictment, without jurisdiction on this case, but they came anyway. … They duped my defence lawyer and the court into this extradition. … I don’t know what to think about it all. It makes me sick to think about it. … I’ve never had a voice, I’ve never been heard.

“It’s a travesty of justice. It’s a miscarriage of justice. …When the FBI came to me in 1987 and 1988, they threatened me if I didn’t cooperate with them. They offered me an immunity deal. I told them I didn’t need immunity, I’ve never done anything where I would need immunity. The theory they laid out, that people in the leadership of AIM ordered Anna Mae to be killed, that never happened. Never ever happened. Not with me, it didn’t.”

He searched for words: “I’ve lost family members, I’ve lost my parents. My youngest daughter is fighting for her life with cancer. I’ve lost nephews. I’ve lost relations. I should be at home with these things.”

John Graham sees himself as little different than the 19th century Ghost Dancers blamed for the original massacre at Wounded Knee — a scapegoat, only this time for the violent American Indian Movement and the 1973 standoff at the iconic Indigenous site.

Extradited more than a decade ago and later convicted in the blood-soaked South Dakota Badlands execution of Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, a 30-year-old Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq woman, Graham maintains his innocence.

Ottawa admitted in the B.C. Court of Appeal this week the now 67-year-old was robbed of procedural fairness by a previous Conservative justice minister in 2010 who amended the original extradition order via a waiver without telling him.

In a brief interview Wednesday from the South Dakota State Penitentiary in Sioux Falls, Graham said he hadn’t been able to watch the two-day Zoom hearing.

He spoke of it giving him hope but exhaled with bitterness:

“I’ve been incarcerated since 2007. I’ve been fighting this case since my U.S. federal indictment in 2003. …They always knew they came to Canada with a defective indictment, without jurisdiction on this case, but they came anyway. … They duped my defence lawyer and the court into this extradition. … I don’t know what to think about it all. It makes me sick to think about it. … I’ve never had a voice, I’ve never been heard.

“It’s a travesty of justice. It’s a miscarriage of justice. …When the FBI came to me in 1987 and 1988, they threatened me if I didn’t cooperate with them. They offered me an immunity deal. I told them I didn’t need immunity, I’ve never done anything where I would need immunity. The theory they laid out, that people in the leadership of AIM ordered Anna Mae to be killed, that never happened. Never ever happened. Not with me, it didn’t.”

He searched for words: “I’ve lost family members, I’ve lost my parents. My youngest daughter is fighting for her life with cancer. I’ve lost nephews. I’ve lost relations. I should be at home with these things.”

Naneek Graham holds a photo of her father John in Vancouver Jan. 11, 2022. B.C. resident John Graham is appealing his extradition to the united states. Graham, a former Yukoner who lived in Vancouver, is accused of killing Anna Mae Pictou-Aquash,a Mi’kmaq activist from Nova Scotia,in 1975 during protests in South Dakota.

PHOTO BY ARLEN REDEKOP /PNG

Born in Whitehorse, Graham is a member of the Southern Tutchone Champagne and Aishihik First Nations.

His daughter, Naneek, moved to Vancouver from Yukon in 2004 to support her father and act as a surety. His five children have been behind him throughout.

Naneek was afraid to hope, too, after sitting through the hearing.

“I went through this before,” she confided. “God, I feel like I hold my breath. Just anxious. It’s a waiting game of not knowing. It’s hard because I went through this before and we had such a bad outcome before. It’s hard for me to let myself get too ahead of myself. I just have to wait.

“It’s just so frustrating and aggravating to be honest. It took me a long time to be able to speak about it. I was just so hurt. I was so angry, so angry I could feel it coming out of my pores. Just being angry about the government on both sides. My dad’s rights were breached big time and he was taken away from us. … They just took him, we didn’t get to say goodbye to him, give him a hug or anything. It was really hard on my sister and I. Then when we got down there, the lawyers put on a big show while my dad was being railroaded the whole time.”

The case rips a scab off an old and deep Canadian legal wound — the decision in December 1976 to extradite AIM leader Leonard Peltier based on evidence fabricated or pressured out of witnesses.

Peltier was convicted in 1977 of the first-degree murder of two FBI agents during the 1975 shootout following the notorious AIM occupation at the site of the U.S. Seventh Cavalry’s 1890 massacre of Oglala Lakota Sioux on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Aquash was shot in the back of the head in 1976 supposedly because she heard Peltier confess.

At the turn of the century, new information surfaced about her slaying and indictments were issued against Graham and Arlo Looking Cloud, an AIM comrade.

Looking Cloud was convicted in 2004 and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Graham was arrested in Vancouver on Dec. 1, 2003, but released on strict conditions while he waged a high-profile battle against extradition. He was returned to the U.S. on Dec. 6, 2007.

After two years of trying to proceed in federal court, however, American prosecutors asked Ottawa to agree to allow Graham to be tried in state court because the justice department lacked jurisdiction.

Graham did not see the decision until August 2011, after he was convicted in the killing of Aquash, a mother of two young girls and a fellow AIM soldier reportedly suspected of being an FBI informant.

A jury acquitted Graham of premeditated murder but convicted him of felony murder and he was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole. His conviction was confirmed on appeal.

Upon learning of the justice minister’s decision, Graham challenged the validity of his extradition and the lawfulness of his subsequent trial.

The U.S. Eighth Circuit Appeal Court said in 2018 it did not have jurisdiction to review the Canadian minister’s decision and Graham must first deal with that before an American court could act.

He remained skeptical he will see freedom:

“Because I won’t lie for the FBI they want me to die in prison, they are trying to make me die in prison. They’ve never produced a case. They have a theory of a case but they have never proven anything. They can’t even place me in the state when this happened. I wasn’t even in South Dakota when this crime happened. I keep telling them over and over. It’s a manufactured case. It’s a fraudulent case.”

He fumed.

“The only people right now really suffering from this case is me and my family. I ask the judges and the minister to put a stop to this. Put a stop to it.”

The panel appeared to agree the waiver should be quashed but the remedy for such breaches usually includes asking the minister to reconsider.

That gave the justices pause because federal lawyers characterized what happened as a kind of technical glitch while robustly dismissing the merits of any argument Graham might raise.

They insisted though that should not suggest the minister had a closed mind.

Graham would be happy to have the waiver simply quashed so he could use the ruling to ask a U.S. court for release.

The division reserved its decision.

Born in Whitehorse, Graham is a member of the Southern Tutchone Champagne and Aishihik First Nations.

His daughter, Naneek, moved to Vancouver from Yukon in 2004 to support her father and act as a surety. His five children have been behind him throughout.

Naneek was afraid to hope, too, after sitting through the hearing.

“I went through this before,” she confided. “God, I feel like I hold my breath. Just anxious. It’s a waiting game of not knowing. It’s hard because I went through this before and we had such a bad outcome before. It’s hard for me to let myself get too ahead of myself. I just have to wait.

“It’s just so frustrating and aggravating to be honest. It took me a long time to be able to speak about it. I was just so hurt. I was so angry, so angry I could feel it coming out of my pores. Just being angry about the government on both sides. My dad’s rights were breached big time and he was taken away from us. … They just took him, we didn’t get to say goodbye to him, give him a hug or anything. It was really hard on my sister and I. Then when we got down there, the lawyers put on a big show while my dad was being railroaded the whole time.”

The case rips a scab off an old and deep Canadian legal wound — the decision in December 1976 to extradite AIM leader Leonard Peltier based on evidence fabricated or pressured out of witnesses.

Peltier was convicted in 1977 of the first-degree murder of two FBI agents during the 1975 shootout following the notorious AIM occupation at the site of the U.S. Seventh Cavalry’s 1890 massacre of Oglala Lakota Sioux on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Aquash was shot in the back of the head in 1976 supposedly because she heard Peltier confess.

At the turn of the century, new information surfaced about her slaying and indictments were issued against Graham and Arlo Looking Cloud, an AIM comrade.

Looking Cloud was convicted in 2004 and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Graham was arrested in Vancouver on Dec. 1, 2003, but released on strict conditions while he waged a high-profile battle against extradition. He was returned to the U.S. on Dec. 6, 2007.

After two years of trying to proceed in federal court, however, American prosecutors asked Ottawa to agree to allow Graham to be tried in state court because the justice department lacked jurisdiction.

Graham did not see the decision until August 2011, after he was convicted in the killing of Aquash, a mother of two young girls and a fellow AIM soldier reportedly suspected of being an FBI informant.

A jury acquitted Graham of premeditated murder but convicted him of felony murder and he was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole. His conviction was confirmed on appeal.

Upon learning of the justice minister’s decision, Graham challenged the validity of his extradition and the lawfulness of his subsequent trial.

The U.S. Eighth Circuit Appeal Court said in 2018 it did not have jurisdiction to review the Canadian minister’s decision and Graham must first deal with that before an American court could act.

He remained skeptical he will see freedom:

“Because I won’t lie for the FBI they want me to die in prison, they are trying to make me die in prison. They’ve never produced a case. They have a theory of a case but they have never proven anything. They can’t even place me in the state when this happened. I wasn’t even in South Dakota when this crime happened. I keep telling them over and over. It’s a manufactured case. It’s a fraudulent case.”

He fumed.

“The only people right now really suffering from this case is me and my family. I ask the judges and the minister to put a stop to this. Put a stop to it.”

The panel appeared to agree the waiver should be quashed but the remedy for such breaches usually includes asking the minister to reconsider.

That gave the justices pause because federal lawyers characterized what happened as a kind of technical glitch while robustly dismissing the merits of any argument Graham might raise.

They insisted though that should not suggest the minister had a closed mind.

Graham would be happy to have the waiver simply quashed so he could use the ruling to ask a U.S. court for release.

The division reserved its decision.

No comments:

Post a Comment