80TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE LIBERATION OF AUSCHWITZ

The liberation of Auschwitz:

What the Soviets discovered on January 27, 1945

Eighty years ago on January 27, 1945, soldiers from Russia's Red Army entered the gates of Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland and were the first to discover the horrors of the concentration camp where more than a million people, most of them Jews, had been murdered. They found just a few thousand survivors in a sprawling complex where the SS had tried to erase all traces of their crimes.

27/01/2025

FRANCE24

By: Stéphanie TROUILLARD

Eighty years ago on January 27, 1945, soldiers from Russia's Red Army entered the gates of Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland and were the first to discover the horrors of the concentration camp where more than a million people, most of them Jews, had been murdered. They found just a few thousand survivors in a sprawling complex where the SS had tried to erase all traces of their crimes.

27/01/2025

FRANCE24

By: Stéphanie TROUILLARD

A photograph of prisoners at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Poland, on the day it was liberated by the Soviet Red Army in January 1945. © Wikimedia

In his Holocaust memoir, "The Truce", Italian prisoner Primo Levi recounted his first contact with the Red Army soldiers when Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp was liberated.

“The first Russian patrol came in sight of the camp about midday on 27 January 1945,” he wrote. “They were four young soldiers on horseback, who advanced along the road that marked the limits of the camp, cautiously holding their sten-guns. When they reached the barbed wire, they stopped to look, exchanging a few timid words, and throwing strangely embarrassed glances at the sprawling bodies, at the battered huts and at us few still alive."

Imprisoned since February 1944 in Monowitz, one of the three camps located in the sprawling concentration camp grounds, Levi witnessed the men's unease as they caught sight of a place that has since become a symbol of Nazi brutality.

“They did not greet us, nor did they smile; they seemed oppressed not only by compassion but by a confused restraint, which sealed their lips and bound their eyes to the funeral scene.”

Facing the ‘unimaginable’

On January 27, 1945, these Soviet soldiers witnessed the unimaginable.

“They were contingents from the first Ukrainian front. The Red Army stumbled upon this site by chance. Going into Auschwitz wasn’t a war goal. You can imagine these people's astonishment as they discovered one concentration camp after another,” said historian Alexandre Bande, a Holocaust specialist.

In his Holocaust memoir, "The Truce", Italian prisoner Primo Levi recounted his first contact with the Red Army soldiers when Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp was liberated.

“The first Russian patrol came in sight of the camp about midday on 27 January 1945,” he wrote. “They were four young soldiers on horseback, who advanced along the road that marked the limits of the camp, cautiously holding their sten-guns. When they reached the barbed wire, they stopped to look, exchanging a few timid words, and throwing strangely embarrassed glances at the sprawling bodies, at the battered huts and at us few still alive."

Imprisoned since February 1944 in Monowitz, one of the three camps located in the sprawling concentration camp grounds, Levi witnessed the men's unease as they caught sight of a place that has since become a symbol of Nazi brutality.

“They did not greet us, nor did they smile; they seemed oppressed not only by compassion but by a confused restraint, which sealed their lips and bound their eyes to the funeral scene.”

Facing the ‘unimaginable’

On January 27, 1945, these Soviet soldiers witnessed the unimaginable.

“They were contingents from the first Ukrainian front. The Red Army stumbled upon this site by chance. Going into Auschwitz wasn’t a war goal. You can imagine these people's astonishment as they discovered one concentration camp after another,” said historian Alexandre Bande, a Holocaust specialist.

A photo taken in January 1945 showing the entrance to the Birkenau camp and its railroad line, after its liberation by Soviet troops. AFP - -

In his latest book, Auschwitz 1945, Bande has tried to shed light on what happened that historic day and in the weeks that followed.

While many books have focused on the workings of Auschwitz-Birkenau, with its selections and extermination process, Bande chose to look at the gaps in the story of its liberation.

“What happened on this site has left such a profound imprint on people's minds that historians, the general public and eye witnesses have been more interested in what occurred during (the liberation) rather than what happened afterwards.”

On the morning of the liberation at the end of January, the Soviet soldiers encountered fierce resistance from German troops. Intense fighting took place on the outskirts of the camp. Once they had overpowered these enemy soldiers, the Red Army discovered a handful of survivors: some 7,000 to 8,000 people. “They were mainly men, women and children who were deemed too incapacitated to be moved,” Bande said.

‘The snow was red with blood’

Just a few days earlier, on January 17, the Germans had begun evacuating Auschwitz-Birkenau. Hitler had ordered that no prisoner should fall into enemy hands alive. Nearly 60,000 people were dragged off in rags onto the roads in the middle of winter, heading west in what became known as the notorious death marches.

“We left in columns of 500. We walked for practically three days and three nights,” Raphaël Esrail, who was deported by convoy no. 67, told FRANCE 24 in 2020.

“What I remember most, and can't forget, are those men and women on the side of the road who had died. They'd been shot in the head by an SS man, or had to walk barefoot for hours. They had fallen as if in prayer, their legs frozen,” he said, recounting the transfer to the Gross-Rosen camp.

“I never expected this. The death marches were harrowing. The snow was red with blood. We were surrounded every 50 metres by the SS,” Léa Schwartzmann, a prisoner on the same convoy who was evacuated to the Ravensbrück camp, said in an interview in 2016.

Before dragging prisoners onto death marches, the SS tried to destroy as much evidence of their crimes as possible. As early as autumn 1944, Nazi authorities were making preparations to abandon Auschwitz-Birkenau. Pits containing the ashes of victims were liquidated, while the crematoria and gas chambers were demolished. When the Soviets entered the camp, however, much of the physical evidence remained.

“When they arrived at the barracks where the bags full of hair were stored, they understood that these were human remains. But it took them some time to understand the reality of the murders of hundreds of thousands of people,” Bande said.

Reconstructing the past

Evidence of the atrocities was captured in pictures by photographers attached to the Red Army. They photographed or filmed the dying in the barracks, the piled-up corpses and the 40,000 pairs of spectacles and 50,000 hairbrushes in storage.

In his latest book, Auschwitz 1945, Bande has tried to shed light on what happened that historic day and in the weeks that followed.

While many books have focused on the workings of Auschwitz-Birkenau, with its selections and extermination process, Bande chose to look at the gaps in the story of its liberation.

“What happened on this site has left such a profound imprint on people's minds that historians, the general public and eye witnesses have been more interested in what occurred during (the liberation) rather than what happened afterwards.”

On the morning of the liberation at the end of January, the Soviet soldiers encountered fierce resistance from German troops. Intense fighting took place on the outskirts of the camp. Once they had overpowered these enemy soldiers, the Red Army discovered a handful of survivors: some 7,000 to 8,000 people. “They were mainly men, women and children who were deemed too incapacitated to be moved,” Bande said.

‘The snow was red with blood’

Just a few days earlier, on January 17, the Germans had begun evacuating Auschwitz-Birkenau. Hitler had ordered that no prisoner should fall into enemy hands alive. Nearly 60,000 people were dragged off in rags onto the roads in the middle of winter, heading west in what became known as the notorious death marches.

“We left in columns of 500. We walked for practically three days and three nights,” Raphaël Esrail, who was deported by convoy no. 67, told FRANCE 24 in 2020.

“What I remember most, and can't forget, are those men and women on the side of the road who had died. They'd been shot in the head by an SS man, or had to walk barefoot for hours. They had fallen as if in prayer, their legs frozen,” he said, recounting the transfer to the Gross-Rosen camp.

“I never expected this. The death marches were harrowing. The snow was red with blood. We were surrounded every 50 metres by the SS,” Léa Schwartzmann, a prisoner on the same convoy who was evacuated to the Ravensbrück camp, said in an interview in 2016.

Before dragging prisoners onto death marches, the SS tried to destroy as much evidence of their crimes as possible. As early as autumn 1944, Nazi authorities were making preparations to abandon Auschwitz-Birkenau. Pits containing the ashes of victims were liquidated, while the crematoria and gas chambers were demolished. When the Soviets entered the camp, however, much of the physical evidence remained.

“When they arrived at the barracks where the bags full of hair were stored, they understood that these were human remains. But it took them some time to understand the reality of the murders of hundreds of thousands of people,” Bande said.

Reconstructing the past

Evidence of the atrocities was captured in pictures by photographers attached to the Red Army. They photographed or filmed the dying in the barracks, the piled-up corpses and the 40,000 pairs of spectacles and 50,000 hairbrushes in storage.

Women prisoners are pictured in their barracks after the liberation in January 1945 of the Auschwitz concentration camp by Soviet troops. AFP - -

“The first series of images taken in the immediate aftermath were of poor quality, due to the lighting conditions and the equipment used,” Bande explained.

“The second set of images is more recognisable. You can see, for example, prisoners falling into the arms of soldiers, but these are reconstructions. They were made by the Soviets in the weeks that followed. The idea was not to dwell on the suffering of the prisoners, but to highlight the heroism of the soldiers of the glorious Red Army.”

For some survivors, liberation did not end the suffering. As Albert Grinholtz, deported on convoy no. 4, recalled in 1991: “The soldiers, shocked by our starvation and skeletal bodies, immediately prepared soup in a wheelbarrow. (...) Closing my eyes, I remember this scene, the first bit of nourishment after so much deprivation and suffering. It caused many casualties among our comrades, who were unable to resist so much food, it was too rich.”

“The first series of images taken in the immediate aftermath were of poor quality, due to the lighting conditions and the equipment used,” Bande explained.

“The second set of images is more recognisable. You can see, for example, prisoners falling into the arms of soldiers, but these are reconstructions. They were made by the Soviets in the weeks that followed. The idea was not to dwell on the suffering of the prisoners, but to highlight the heroism of the soldiers of the glorious Red Army.”

For some survivors, liberation did not end the suffering. As Albert Grinholtz, deported on convoy no. 4, recalled in 1991: “The soldiers, shocked by our starvation and skeletal bodies, immediately prepared soup in a wheelbarrow. (...) Closing my eyes, I remember this scene, the first bit of nourishment after so much deprivation and suffering. It caused many casualties among our comrades, who were unable to resist so much food, it was too rich.”

A photograph showing the entrance to the Auschwitz I camp. This scene may have been reconstructed several days after the camp's liberation. © Wikimedia

Symbolic of the Holocaust

Survivors took weeks, sometimes months, to return to their home town or country. Of the almost 69,000 people transported from France to Auschwitz-Birkenau, only 3% ever returned home. In the aftermath of the liberation, the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp was repurposed. The Soviets interned German prisoners of war and Poles suspected of collaboration there, while locals scoured the many barracks that were torn down salvaging scraps of timber. Trials and executions were also held at Auschwitz, including that of former camp commander Rudolf Höss.

In 1947, a memorial museum was finally opened to “protect the site and ensure knowledge is passed down of the crimes committed there”. Eighty years on, Auschwitz-Birkenau has become an important place of remembrance, symbolic of the Holocaust. Last year, it welcomed 1.83 million visitors.

“It's a symbol, especially in France, because the majority of Jewish deportees died there, but also because it's one of the best-preserved sites. It's more difficult attracting hundreds of thousands of tourists to a simple monument or memorial,” Bande explained.

“Auschwitz allows us to show the magnitude of the atrocities.”

This article has been translated from the original in French by Nicole Trian.

Symbolic of the Holocaust

Survivors took weeks, sometimes months, to return to their home town or country. Of the almost 69,000 people transported from France to Auschwitz-Birkenau, only 3% ever returned home. In the aftermath of the liberation, the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp was repurposed. The Soviets interned German prisoners of war and Poles suspected of collaboration there, while locals scoured the many barracks that were torn down salvaging scraps of timber. Trials and executions were also held at Auschwitz, including that of former camp commander Rudolf Höss.

In 1947, a memorial museum was finally opened to “protect the site and ensure knowledge is passed down of the crimes committed there”. Eighty years on, Auschwitz-Birkenau has become an important place of remembrance, symbolic of the Holocaust. Last year, it welcomed 1.83 million visitors.

“It's a symbol, especially in France, because the majority of Jewish deportees died there, but also because it's one of the best-preserved sites. It's more difficult attracting hundreds of thousands of tourists to a simple monument or memorial,” Bande explained.

“Auschwitz allows us to show the magnitude of the atrocities.”

This article has been translated from the original in French by Nicole Trian.

Newly discovered photos of Nazi deportations show Jewish victims as they were last seen alive

Deportation of Jews in Bielefeld, Germany, on Dec. 13, 1941.

The Conversation

January 26, 2025

The Holocaust was the first mass atrocity to be heavily photographed.

The mass production and distribution of cameras in the 1930s and 1940s enabled Nazi officials and ordinary people to widely document Germany’s persecution of Jews and other religious and ethnic minorities.

I co-direct an international research project to collect every available image documenting Nazi mass deportations of Jews, Roma and Sinti, as well as euthanasia victims, in Nazi Germany between 1938 and 1945. The most recently discovered series of images will be unveiled on Jan. 27, 2025 – Holocaust Remembrance Day.

In most cases, these are the very last pictures taken of Holocaust victims before they were deported and perished. That fact gives the project its name, #LastSeen.

A few of the images we’ve tracked down were taken by Jewish people, not Nazi officials, offering a rare glimpse of Nazi mass deportations from a victim’s perspective. As descendants of survivors help our researchers identify the deportees in these images and tell their stories, we give previously faceless victims a voice.

The Holocaust was the first mass atrocity to be heavily photographed.

The mass production and distribution of cameras in the 1930s and 1940s enabled Nazi officials and ordinary people to widely document Germany’s persecution of Jews and other religious and ethnic minorities.

I co-direct an international research project to collect every available image documenting Nazi mass deportations of Jews, Roma and Sinti, as well as euthanasia victims, in Nazi Germany between 1938 and 1945. The most recently discovered series of images will be unveiled on Jan. 27, 2025 – Holocaust Remembrance Day.

In most cases, these are the very last pictures taken of Holocaust victims before they were deported and perished. That fact gives the project its name, #LastSeen.

A few of the images we’ve tracked down were taken by Jewish people, not Nazi officials, offering a rare glimpse of Nazi mass deportations from a victim’s perspective. As descendants of survivors help our researchers identify the deportees in these images and tell their stories, we give previously faceless victims a voice.

Jewish Germans assemble for deportation in Breslau, Germany, in November 1941. Courtesy of Regional Association of Jewish Communities in Saxony, Germany, CC BY-SA

A growing archive

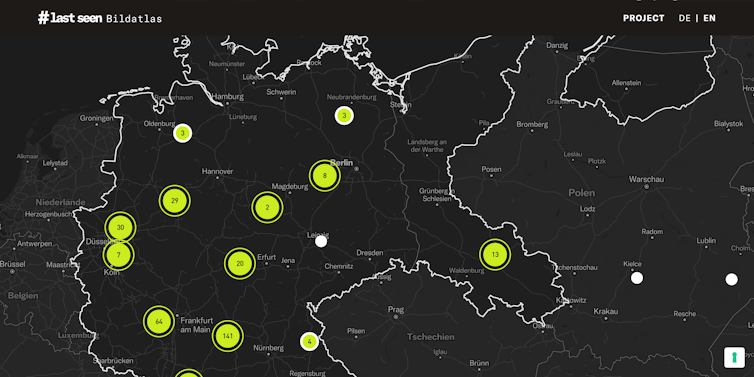

The #LastSeen project is a collaboration between several German academic and educational institutions and the USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide Research in the United States. When it began in late 2021, researchers knew of a few dozen deportation images of Jews from 27 German towns that had been gathered for a 2011-2012 exhibition in Berlin.

After contacting 1,700 public and private archives in Germany and worldwide to find more, #LastSeen has now collected visual evidence from 60 cities and towns in Nazi Germany. Of these, we’ve analyzed 36 series containing over 420 images, including dozens of never-before-seen photo series from 20 towns.

Most photographs of Nazi mass deportations from local archives published in our digital atlas were taken by the perpetrators, who documented the event for the police or municipality. That has heavily shaped our visual understanding of these crimes, because they display victims as a faceless mass. When individuals were depicted, it was most often through an antisemitic lens.

The LastSeen digital atlas shows locations of deportations where visual documentation has been uncovered. Screenshot, LastSeen, CC BY-SA

We have, however, obtained a handful of images taken from a victim’s perspective. In January 2024, the #LastSeen team shared newly discovered photographs showing the Nazi deportations in what was then Breslau, Germany – today Wroclaw, Poland.

They were sent to us for analysis by Steffen Heidrich, a staff member of the Regional Association of Jewish Communities in Saxony, Germany, who came across an envelope titled “miscellaneous” while reorganizing his archive. It contained 13 deportation photographs – the last images taken of dozens of Jewish victims before they were transported from Breslau to Nazi-occupied Lithuania and massacred in November 1941.

Jewish resistance

Many of these pictures in this series show a large, mixed age group of men and women wearing the yellow star – the notorious Nazi-mandated sign for Jews – gathering outside with bundles of their belongings. Some are taken from a peculiar angle, from behind a tree or a wall, suggesting they were snapped clandestinely.

We have, however, obtained a handful of images taken from a victim’s perspective. In January 2024, the #LastSeen team shared newly discovered photographs showing the Nazi deportations in what was then Breslau, Germany – today Wroclaw, Poland.

They were sent to us for analysis by Steffen Heidrich, a staff member of the Regional Association of Jewish Communities in Saxony, Germany, who came across an envelope titled “miscellaneous” while reorganizing his archive. It contained 13 deportation photographs – the last images taken of dozens of Jewish victims before they were transported from Breslau to Nazi-occupied Lithuania and massacred in November 1941.

Jewish resistance

Many of these pictures in this series show a large, mixed age group of men and women wearing the yellow star – the notorious Nazi-mandated sign for Jews – gathering outside with bundles of their belongings. Some are taken from a peculiar angle, from behind a tree or a wall, suggesting they were snapped clandestinely.

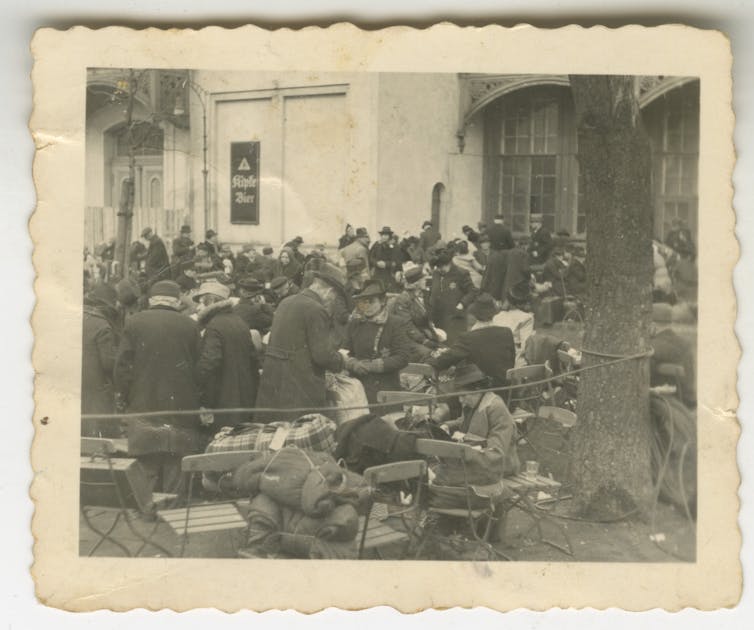

People waiting for deportation in Breslau in November 1941. Courtesy of Regional Association of Jewish Communities in Saxony, Germany, CC BY-SA

Given the deportation assembly point for the Breslau Jews, a guarded local beer garden, our researchers knew that only a person with permission to access that property could have shot these pictures.

For these two reasons, we concluded that an employee of the Jewish community of Breslau must have documented the Nazi crimes – most likely Albert Hadda, a Jewish architect and photographer who clandestinely photographed the November 1938 pogrom in Breslau.

Hadda’s marriage to a Christian partially protected him from persecution. Between 1941 and 1943, the city’s Jewish community tasked him with caring for the deportees at the assembly point until their forced removal.

These 13 recently discovered pictures constitute the most comprehensive series illuminating the crime of mass deportations from a victim’s perspective in Nazi Germany. Their unearthing is testimony to the recently rediscovered widespread individual resistance by ordinary Jews who fought Nazi persecution.

Documenting Fulda

Our project has also identified new deportation photos taken in the German town of Fulda in December 1941, during a snowstorm.

Previously, historians knew of only three pictures of this deportation event. Preserved in the city archive, they show the deportees at the Fulda train station during heavy snowfall.

We discovered two new images of the same Nazi deportation, apparently taken by the same photographer, in a videotaped survivor interview in the Visual History Archive of the USC Shoah Foundation in Los Angeles.

In 1996, the Shoah Foundation interviewed Miriam Berline, née Gottlieb, the daughter of a successful Orthodox Jewish merchant in Fulda. At the end of the two-hour interview, Berline held two photographs up to the camera. They clearly show the same snowy deportation in Fulda. Screenshot from Miriam Berline’s interview about the Fulda deportations. USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, CC BY-SA

Berline, born in 1925, escaped Nazi Germany in 1939. She did not remember how her family obtained the images but recalled the photographer as Otto Weissbach, a “wonderful” man who had helped Fulda’s Jewish families.

Our researchers investigated and learned his name was Arthur Weissbach, a non-Jewish neighbor of the Gottliebs. The factory he owned still exists. Descendants of Jewish families have since confirmed that he kept valuables for them and took care of elderly relatives who stayed behind.

Weissbach’s niece said he was a passionate hobby photographer. Since Weissbach kept contact with survivors after the war, he might have given the images to the Gottlieb family. Today, the family’s copies are lost, but their existence is preserved in Berline’s video interview at the USC Shoah Foundation.

The pictures show the Jews at the Fulda train station on Dec. 8, 1941 – revealing how Nazi deportations happened in plain view.

The day before, Jewish men and women from around Fulda had been summoned and spent the night at a local school gym. In the morning, they were taken to the train station and forced by police to board a train to Kassel, in central Germany, and then eastward onto Riga, in Nazi-occupied Latvia.

In total, 1,031 Jews were deported from Kassel to Riga. Only 12 from Fulda survived.

Identifying the deportation victims

It is difficult to identify the people in the photos we discover. So far, we’ve published 279 biographies in the digital atlas.

In the future, artificial intelligence may help us identify more people from the photos in our collection. But for now, this process takes exhaustive research with the help of local researchers and descendants of survivors, whose names are known from archived transport lists.

Families often struggle to recognize individuals in these images, but sometimes they have family photos that help us do so.

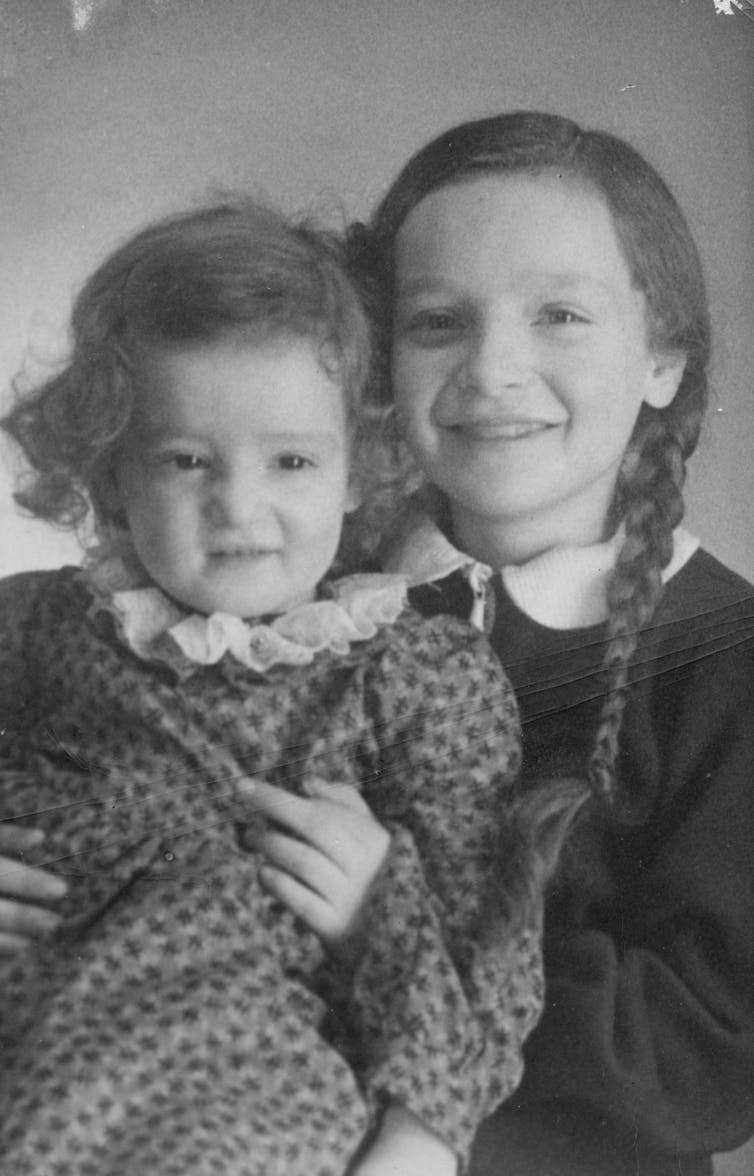

Take, for example, this posed family portrait of two young girls. They are Susanne and Tamara Cohn

Given the deportation assembly point for the Breslau Jews, a guarded local beer garden, our researchers knew that only a person with permission to access that property could have shot these pictures.

For these two reasons, we concluded that an employee of the Jewish community of Breslau must have documented the Nazi crimes – most likely Albert Hadda, a Jewish architect and photographer who clandestinely photographed the November 1938 pogrom in Breslau.

Hadda’s marriage to a Christian partially protected him from persecution. Between 1941 and 1943, the city’s Jewish community tasked him with caring for the deportees at the assembly point until their forced removal.

These 13 recently discovered pictures constitute the most comprehensive series illuminating the crime of mass deportations from a victim’s perspective in Nazi Germany. Their unearthing is testimony to the recently rediscovered widespread individual resistance by ordinary Jews who fought Nazi persecution.

Documenting Fulda

Our project has also identified new deportation photos taken in the German town of Fulda in December 1941, during a snowstorm.

Previously, historians knew of only three pictures of this deportation event. Preserved in the city archive, they show the deportees at the Fulda train station during heavy snowfall.

We discovered two new images of the same Nazi deportation, apparently taken by the same photographer, in a videotaped survivor interview in the Visual History Archive of the USC Shoah Foundation in Los Angeles.

In 1996, the Shoah Foundation interviewed Miriam Berline, née Gottlieb, the daughter of a successful Orthodox Jewish merchant in Fulda. At the end of the two-hour interview, Berline held two photographs up to the camera. They clearly show the same snowy deportation in Fulda. Screenshot from Miriam Berline’s interview about the Fulda deportations. USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, CC BY-SA

Berline, born in 1925, escaped Nazi Germany in 1939. She did not remember how her family obtained the images but recalled the photographer as Otto Weissbach, a “wonderful” man who had helped Fulda’s Jewish families.

Our researchers investigated and learned his name was Arthur Weissbach, a non-Jewish neighbor of the Gottliebs. The factory he owned still exists. Descendants of Jewish families have since confirmed that he kept valuables for them and took care of elderly relatives who stayed behind.

Weissbach’s niece said he was a passionate hobby photographer. Since Weissbach kept contact with survivors after the war, he might have given the images to the Gottlieb family. Today, the family’s copies are lost, but their existence is preserved in Berline’s video interview at the USC Shoah Foundation.

The pictures show the Jews at the Fulda train station on Dec. 8, 1941 – revealing how Nazi deportations happened in plain view.

The day before, Jewish men and women from around Fulda had been summoned and spent the night at a local school gym. In the morning, they were taken to the train station and forced by police to board a train to Kassel, in central Germany, and then eastward onto Riga, in Nazi-occupied Latvia.

In total, 1,031 Jews were deported from Kassel to Riga. Only 12 from Fulda survived.

Identifying the deportation victims

It is difficult to identify the people in the photos we discover. So far, we’ve published 279 biographies in the digital atlas.

In the future, artificial intelligence may help us identify more people from the photos in our collection. But for now, this process takes exhaustive research with the help of local researchers and descendants of survivors, whose names are known from archived transport lists.

Families often struggle to recognize individuals in these images, but sometimes they have family photos that help us do so.

Take, for example, this posed family portrait of two young girls. They are Susanne and Tamara Cohn

Susanne and Tamara Cohn, circa 1939. Private Archive, CC BY-SA

Relatives of the Cohn family had this photo. It, along with data from the local Nazi transport list, established that two girls photographed in one of his Breslau deportation shots were the daughters of Willy Cohn.

Cohn, a well-known German-Jewish medieval historian and high school teacher in Breslau, kept a detailed diary about the persecution of the town’s Jews from 1933 to 1941. It was unearthed and published in the 1990s.

This photo, below, may be the last picture ever taken of his children with their mother, Gertrud.

Relatives of the Cohn family had this photo. It, along with data from the local Nazi transport list, established that two girls photographed in one of his Breslau deportation shots were the daughters of Willy Cohn.

Cohn, a well-known German-Jewish medieval historian and high school teacher in Breslau, kept a detailed diary about the persecution of the town’s Jews from 1933 to 1941. It was unearthed and published in the 1990s.

This photo, below, may be the last picture ever taken of his children with their mother, Gertrud.

Gertrud, Susanne and Tamara Cohn, Breslau, November 1941.

New insights

The #LastSeen research project is generating new insights into the history of Nazi mass deportations, new methodologies for photo analysis and new tools for Holocaust education.

In addition to the digital atlas, which has been visited by more than 50,000 people since its launch in 2023, we have developed several award-winning educational tools, including an online game that invites students to search for clues, facts and images of Nazi deportations in an artificial attic.

In workshops for teachers and seminars with students, #LastSeen teaches the history of Nazi deportations and demonstrates how historical photo research works. In Fulda, for example, high schoolers helped us locate the exact places where the photographs were taken.

Those pictures will be published in our atlas on Holocaust Remembrance Day 2025. A public commemoration in Fulda will feature the local students’ contributions.

Depending on fundraising, we hope to extend the #LastSeen project beyond Germany. Collecting images from all 20-plus European countries annexed or occupied by the Nazis will help us better understand these crimes and advance research and education in new ways.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to correct the date of the Fulda deportations.

Wolf Gruner, Professor of History, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment