Greece and Turkey – a Millennium of Warfare — and the Fading West

Prologue

For about a millennium the Mongol Turks have been targeting the Greeks. The Mongol Turks first appeared in the neighborhood of the Greek medieval empire in the 11th century. In 1071, they defeated the Greeks in the Battle of Manzikert. The Mongols captured most of Asia Minor, which was the cultural and geographical capital of the Greek medieval kingdom. The Turks forced the Greeks of Asia Minor to become Moslems.

The next international crisis that assisted the growth of Mongol power was the crusades. Fanaticism caught fire among Christians and Moslems. Both Christian and Islamic armies fought countless battles in order to justify the superiority of their imaginary god. Theology became strategy and war and mayhem and conquests. The strategy of the “war on terror” of the 21st century dates from the crusades. And in the dark ages (4th to 14th centuries) and the twenty-first century the results were the same: abuse of religion, plagues, human destitution and massive destruction for the political purposes of Empire.

The Mongol Turks played a decisive role in the emergence of the Islamic State / Empire. But the Fourth Christian Crusade of 1204 prepared the Mongols’ final conquest of Greece in 1453.

The fourth crusade, 1204

Conquest of Constantinople by the 1204 crusaders. Miniature in La Conquete de Constantinople by Geoffroy de Villehardouin, Venetian ms, c. 1330. Wikipedia.

Picture showing the victorious crusaders entering captured Constantinople, 1204. Painting by Eugena Delacroix, 1840. Public Domain

Venetians, Germans and French troops made up the army of the Fourth Crusade. Their original purpose was to free the “Holy Land” from Moslems. But in passing by Constantinople, the capital of the medieval Greek empire, they changed their strategy. Militant theology took second place to greed for immediate enrichment. They could see Constantinople was full of palaces and churches and riches. They found a local prince who promised them gold for putting him on the imperial throne. The crusaders were delighted with the local Ephialtes, traitor. They attacked Constantinople and captured it. Like savages, they started looting, raping, slaughtering, and burning. They even set the libraries on fire. But with the capture of the capital, Constantinople, the rest of the country came under the control of the Western Christian barbarians who looked at the Greek Orthodox Christians as heretics deserving Dante’s inferno. They divided Greece into Western principalities, fatally weakening Greek control and, thus, preparing the final onslaught by the Mongol Turks in 1453.

The fall of Constantinople, 1453

Fall of Constantinople, May 29, 1453. Mural from Cafe of G. Antikas, island of Skopelos. Picture depicting the emperor Constantine Palaiologos ready for battle. Public Domain

The Greeks recovered Constantinople in 1254, 50 years after the tragic fall to the crusaders. But, basically, it was too late. The crusaders had smashed the unity, military and administrative strength, and economy of Greece. At the same time, the Mongol Turks kept attacking and grabbing Greek territory. By mid-fifteenth century, Constantinople and Peloponnesos in mainland Greece remained free. But even during those desperate times, efforts continued to resist the Turks. The Orthodox and Catholic churches united under the Pope. The Greeks hoped that the Pope would launch a crusade against the Turks and the European powers would join the Pope and the Greeks. Unfortunately, the Schism of 1054 between East and West had done its deleterious theological job all too well. The population of Constantinople nearly lynched the representatives of the Greek King who wanted the Union of the churches. The propaganda that won the day said, “Better the turban of the Sultan than the Tiara of the Pope.” And, besides, the European powers turned the Pope down. They were not about to go to war over the “heretical” Greeks.

George Gemistos Plethon

A Greek Platonic philosopher, George Gemistos Plethon, sent a memorandum to the King in which he proposed a strategy to face and defeat the Mongol Turks. First of all, he said to the King “let’s defend Peloponnesos, the most Greek region of Hellas. But let’s defend our freedom with Greek troops, not Western mercenaries. Confiscate the land of the monasteries and churches and distribute it to landless Greeks who would fight the Turks. And, finally, abolish Christianity and bring back Hellenic religious traditions, the theater, the Oracle of Delphi, festivals, the Olympics, and piety, Eusebeia for the gods.”

The King rejected Plethon’s proposal, and, on May 29, 1453, Constantinople fell to the Mongol Turks. For the next four centuries Greece and the Greeks disappeared. The buffer free Greeks offered Europe no longer existed and the Turks occupied all of southeastern Europe, spreading the dark ages to modern times until the Greeks revolted in 1821.

The Greek Revolution, 1821

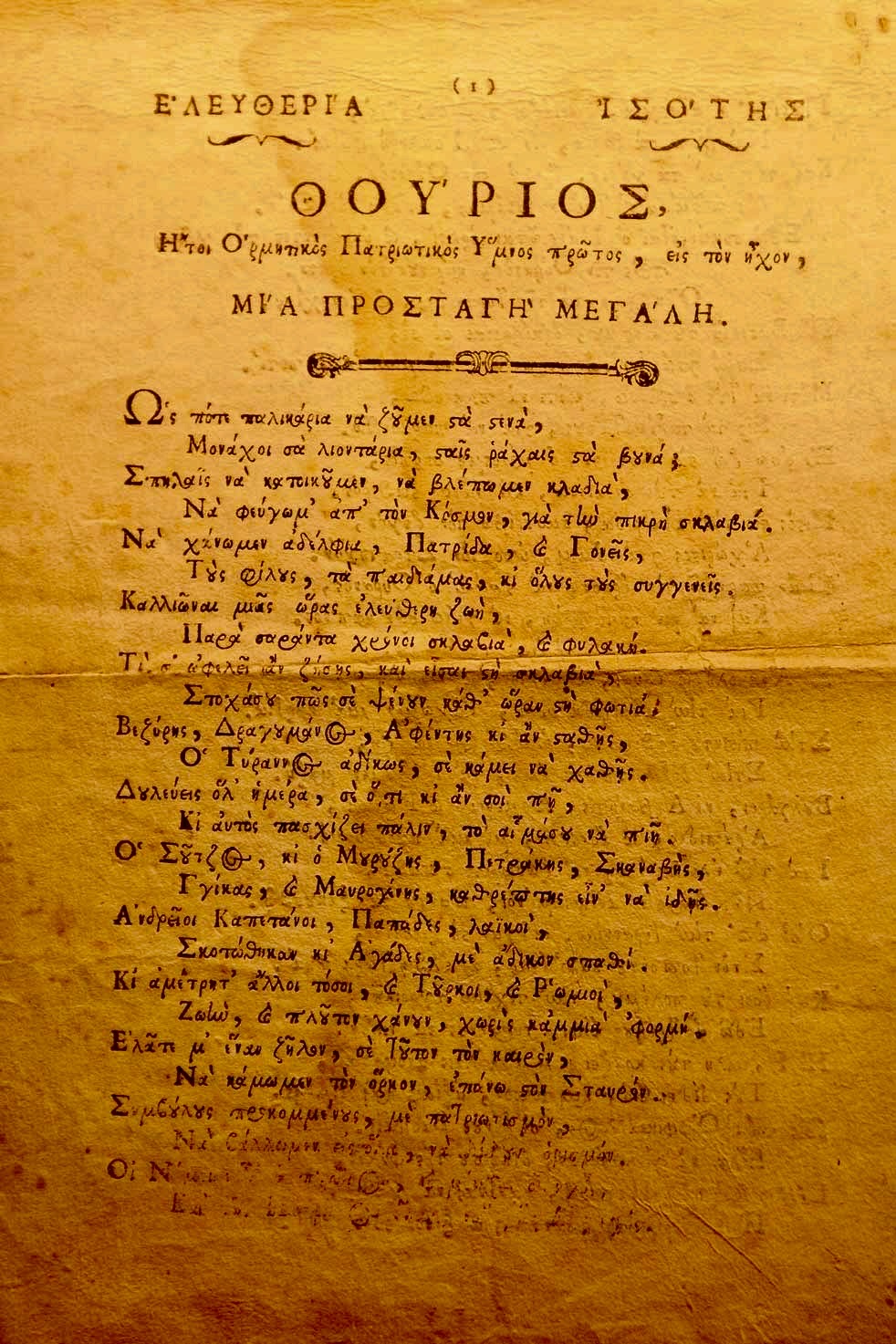

Rigas Pheraios, Hymn to Freedom, Thourios, 1797 (Ρήγας Φεραίος, ΕΛΕΥΘΕΡΙΑ ΙΣΟΤΗΣ, ΘΟΥΡΙΟΣ). Public Domain.

With the exception of Russia that opened its borders to Greek refugees and the Italian City States of Padua, Florence, and Venice that welcomed Greek intellectuals that brought to Europe ancient Hellenic books on science and philosophy, the rest of monarchical Europe minded its business. This meant trading and supporting the Mongol Turks ruling Christians in Europe.

The Renaissance that Greek works on mathematics, astronomy, engineering and, to a lesser extent, philosophy, reawakened in Europe created our world. Yet the European beneficiaries of this reawakening did not think of thanking and helping the descendants of the ancient Greeks who had lost their freedom in 1453. In fact, religious prejudice among Europeans made modern Greeks not merely invisible in relation to their glorious ancestors, but Western Europeans lost no sleep over their wretched status under Mongol Turkish rule. European monarchs did not exactly treat their people much better than the Islamic rulers of Christian people. The Europeans failed to connect the treasures of ancient Greek science and civilization with living Greeks.

Only the Greek Revolution of 1821 shook the conscience of some educated Europeans and started connecting their Hellenic education with the heroic acts of the Revolution, thus giving birth to Philhellenism. The ferocity and atrocities of the Mongol Turkish response to the Revolution also spread Philhellenism and may have contributed to the successful 1827 military intervention of Russia, England and France on behalf of the revolutionaries. The great powers, Russia, England, and France appointed Ioannes Kapodistrias to govern liberated Greece. Kapodistrias was a superb European diplomat and Greek patriot. His service as the Secretary of State of Russia, 1816-1822, gave him enormous reputation and power. He was probably the best Greek politician since Pericles. He wanted a country independent of all foreign and sectarian domestic interest and influence. However, his commitment to Greek freedom and democratic virtues was his undoing. His Greek and foreign enemies murdered him on September 27, 1831.

Greece without the genius and Hellenic virtues of Kapodistrias rapidly degenerated to a second tier power. Both Europeans and Americans and Turks joined hands to manage Greece. And, of course, Turkey kept manipulating America’s fear of Russia to extract more favors and sovereignty from Greece. The Greeks and Turks fought wars in 1897, 1912-1913, 1920s. In 1912-1913, Greece doubled its territory. But in the 1920-1923, the allies, especially England, abandoned Greece and the Greeks lost their last chance to recover Asia Minor from the Mongol Turks. Then, the British lost their war in Cyprus and took revenge by the treaties they designed that brough the Turks back to Cyprus and encouraged the Turks to launch their pogrom of the 85,000 Greeks in Istanbul. That barbarism took place in 1955. It destroyed the stores and livelihood of the Greeks in Istanbul. The next calamity was the encouragement of Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Gerard Ford of the Turks to capture northern Cyprus in 1974, all a bribe to keep the Turks in NATO. So, why would Western powers like England, and especially the Unites States favor the Jihadist and anti-Western Islamic Mongol Turkey rather than Greece, the country that civilized them?

The Imia crisis, 1996

Imia is one of the Dodecanese Greek islands in southeast Aegean Sea. NASA

We get clues and some understanding of this paradox of US foreign policy from the 1996 crisis of Imia. The American ambassador to Greece, Thomas M. T. Miles, revealed the story of the Greco-Turkish confrontation over Imia, an uninhabitable tiny Greek island about 4 miles from the Turkish coast and close to the island of Kalymnos in the eastern Aegean. On June 5, 1998, Miles was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy for an oral foreign affairs history project. The script of the conversation is kept in the Library of Congress.

Miles insisted his effort as an American ambassador in Athens was “to keep Greece and Turkey from going to war with each other.” He noticed that in late 1995 relations between Greece and Turkey deteriorated sharply. The prime minister of Turkey, Tansu Ciller was not reelected, though she remained as a caretaker prime minister. Then, Miles says, “a strange set of incidents began around the tiny island of Imia… A Turkish coastal freighter, sometime around December 10, 1995, ran aground on Imia. A Greek Coast Guard cutter from Kalymnos came by and offered to help pull the ship off the rocks. The Turkish ship said it did not need any help from the Greeks because Imia was a Turkish island. The Greeks said no it is not, and they pulled the ship off.” Miles reports that after that strange incident, the Greek and Turkish governments during late 1995 and early 1996 started sending diplomatic notes to each other while Greeks and Turks went to Imia and set their national flag or tore down the flag of the other side.

“Athens, Miles says, “was in a state of patriotic outrage. Ships were sent to the Aegean. Pretty soon you had the makings of a full-blown crisis.” Meanwhile, like in Turkey, the Greek prime minister, Andreas Papandreou resigned for health reasons. This took place on January 1996. The new prime minister was Constantine Simitis.

Miles says both the prime ministers of Turkey and Greece “had to deal with was the mounting crisis around Imia. I was in constant touch with the government, warning them against taking any rash steps. On the morning of the January 29, 1996, we learned that Greek forces had landed on Imia. I called the Minister of Defense, and he confirmed that troops had landed on Imia. I told him he needed to get them out and he replied that he could not remove the troops from Greek territory. I called the Prime Minister and repeated my position, warning that the Turkish response might be unpredictable. I also alerted the Operations Center and my counterpart in Ankara that we might be in for a rough ride… One of the problems was that the Greek Chief of Staff, Admiral Limberis, was an ultra-nationalist and very difficult to deal with… Minister of Defense [Gerasimos] Arsenis had a good relationship with Secretary Perry. During the day of January 29 and into the night of January 29/30, the crisis intensified with more than ten ships from the two navies in the narrow area around Imia, along with planes and helicopters. The weather was terrible. I was in the office about 1:00 a.m. President Clinton had been on the phone with Simitis, Secretary Christopher had been on the phone with [foreign minister] Pangalos, I was in touch with both of them… About 2:00 a.m. we learned that the Turks had landed forces on another tiny island… very near Imia. At about the same time, a Greek helicopter crashed in the area, killing three crew members. It seemed that the crash was weather-related, but you could not be sure. It was a tense time. But, ironically, the fact that the Turks had troops on one tiny island and the Greeks had troops on Imia created a basis on which both could agree to withdraw their forces, and the crisis began to wind down around 3:00AM. Keep in mind that Imia is about 4 hectares in area (9 acres), with no inhabitants and no water. The key to life in the Aegean is fresh water, although there are some islands that have their water sent in by tanker. The reason why sovereignty over Imia is important is that it lies only 4 miles off the Turkish coast and that with sovereignty over the tiny islands comes control over the adjacent waters and the seabed. In any case, around 3:00 am Athens and Ankara time, which would have been about 8:00 p.m. Washington time, an agreement was reached that the troops would be pulled off both tiny islands. Tragically, as I said, in the process a Greek helicopter crashed, and three crew members were killed. They were the only fatalities. The Greek press blamed us for the accident. When we asked some of the journalists who made that claim how we could have caused the accident, they responded that we could do anything with satellites or through some other means. I went to the funeral, and it was very sad, as you can imagine. The thing that was remarkable was that more people weren’t killed. This crisis began to wind down on January 30.”

Then Niles tried to explain away the madness, may schizophrenia, of American foreign policy toward Greece and Turkey, always finding excuses to side with Turkey and against Greece.

US: We took the position that we would not take a position

“We took the position, he says, “that we would not take a position on the sovereignty issue but that we would encourage the states, Greece and Turkey, to work it out. We said that we generally agreed with the Greek position that [despite the Greek sovereignty of Imia] this was something that should go to the International Court of Justice. I personally think that was a big mistake. We knew by the time we took this position that the Greeks were right on the sovereignty argument, [that Imia was Greek].”

The State Department also tried to dismiss the Imia crisis, saying, “The United States has no position on which country has sovereignty over the islet, according to State Department spokesman Nicholas Burns.”

America’s no position made the Turks more aggressive towards the Greeks

“The Turks knew,” Miles continued, “that we knew their position was very weak. When we refused to take a position it sent a signal back to the Turks that we prepared to countenance or not do anything about aggressive Turkish behavior toward the Greeks on the territorial issues in the Aegean. We did not want to offend an important ally, Turkey, but what this led to was a succession of Turkish claims and statements about the Aegean territorial issues that poisoned the relationship with Greece even further. At the time of the crisis, Mrs. Ciller talked about “thousands of islands, islets and rocks” whose sovereignty was uncertain. Mr. Gonensay, the Foreign Minister in the subsequent government, talked about “gray areas” in the Aegean. In May of 1996 the Turks raised an issue about a small island called Gavdhos, which is south of Crete. We took a strong stance and said that Gavdhos was a Greek island. Recently in the fall of 1998, the Turks raised questions about several other Greek islands, including Farmakonisi, which is inhabited. What this does in Greece, of course, is scare people and put pressure on the Greek government to be very tough in any dealing with the Turks because they see the Turks as threatening Greek sovereignty and trying to seize Greek territory… The Turks at one point said frankly to us that they knew they would lose a case on Imia in the International Court of Justice, but they would be prepared to allow that to happen as long as they could balance the loss with a victory. If they were to allow the issue of Imia to go to the Court of Justice, they wanted the issue of the militarization of the Dodecanese Islands to be taken up by the International Court of Justice simultaneously. The Treaty of Paris of 1947 was the peace treaty with Italy to which Greece and the US were signatories, but Turkey was not. It ended Italy’s participation in World War II and, inter alia, transferred the Dodecanese Islands to Greece. The Treaty of Paris also stated that the Dodecanese Islands must be demilitarized. The Greeks claim that until the invasion of Cyprus by Turkey in 1974 they observed those provisions. I have no reason to doubt that. After 1974, using article 51 of the United Nations Charter, which is the right to self- defense, the Greeks claim that the use of force by the Turks in Cyprus gives them the right to station forces on the Dodecanese Islands since the Turks might use force against Rhodes, which is very near Turkey, or one of the other islands. The real life situation is that because of the geography of the area, the Dodecanese being right along the coast of Turkey and far from mainland Greece, it would be impossible for the Greeks to defend the Dodecanese against a Turkish invasion… It is a little bit like the Berlin brigade defending West Berlin against the three encircling Soviet tank armies. But the Greeks felt they had to be there militarily so that their people would feel more secure. I didn’t really buy that because the people on Rhodes knew that the garrison on Rhodes would not be able to fend off the Turks if they really invaded. All of our efforts to get the Imia issue to a resolution failed. When I left Athens on September 27, 1997, the issue was unresolved. To this day it remains a problem. [Turks and Greeks] wanted us to stop them [from going to war]. I am sure that in their hearts they did.” (emphasis mine)

Perhaps they did. But the Imia crisis revealed the shameful American retreat of supporting Greece which owned Imia. The American diplomats and President Clinton knew that Imia was Greek. Yet they forced Greece to a humiliating retreat, which encouraged the Turks to keep their relentless military threats in the Greek Aegean Sea, thus diminishing Greek sovereignty, a situation bound to explode in war. Erdogan of Turkey keeps talking of the Turks’ blue homeland in the Aegean.

Skopje, not Macedonia

Miles expressed the same arrogance of the US as the only player solving European / Greek problems like the case of taking a former province of Yugoslavia with the stolen Greek name of Macedonia, which the US recognized as an independent state. Miles says that [the case of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia] “was a little like Imia in that there wasn’t anyone else to do the job, and if the United States hadn’t been available to do the job, it wouldn’t have happened. Certainly Greece and FYROM would not have gone to war but relations between them would have remained frozen. They simply did not have the ability, in part because of domestic politics, to do it on their own, and there was no one else out there that could have brought them together.”

What Miles is saying is that American diplomats created the Slavic state of Skopje (Northern Macedonia) for the ideological satisfaction of illusions they had about communism and Russia. That process of Empire ignored the harm they caused to the Greeks. History apparently was for the victors to write and rewrite.

Debt colonialism

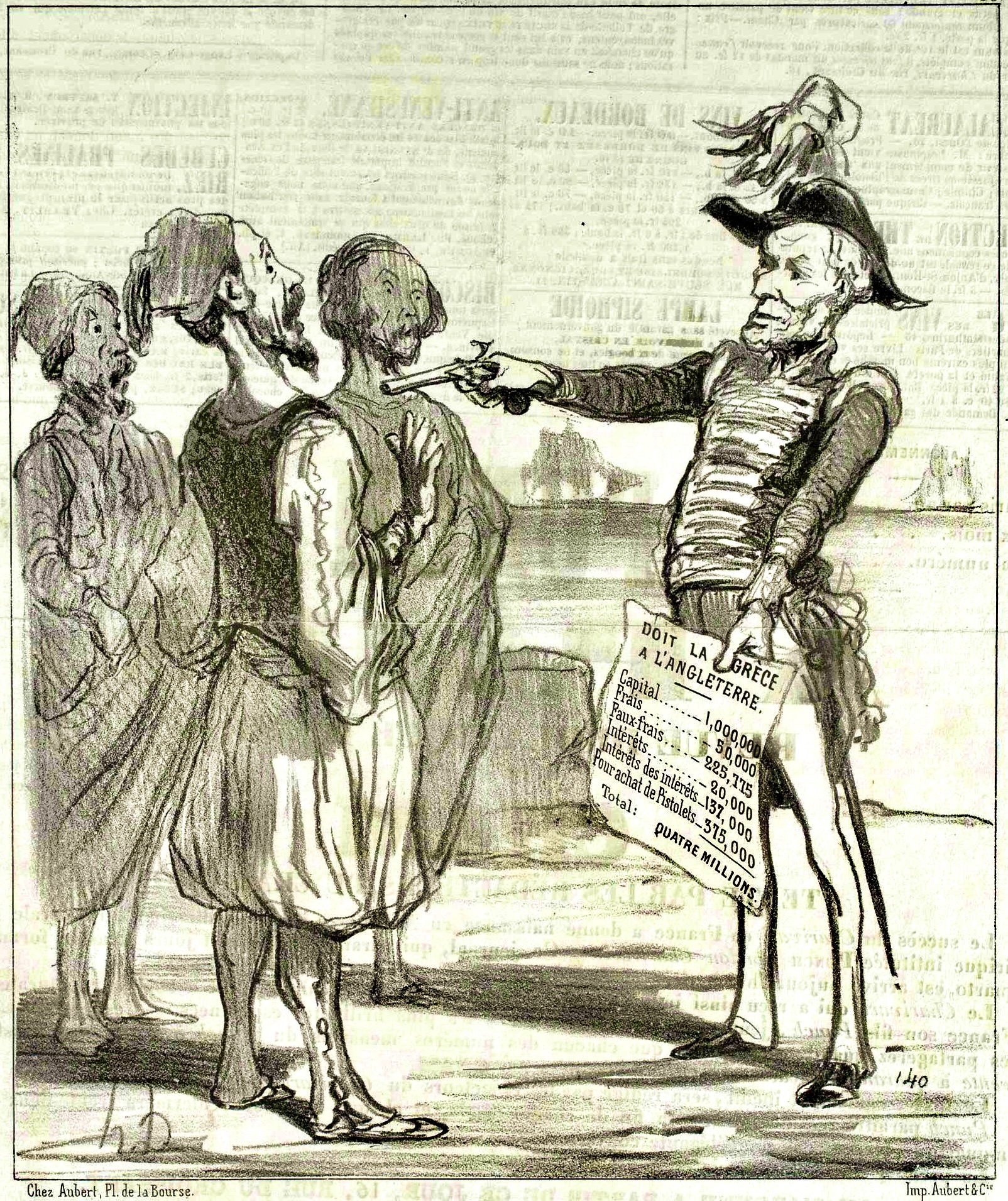

Cartoon by the French Alphonse Daumier satirizing the debt of Greece to the Great Powers, 1850. The country was bankrupt by the end of the 19th century. It lived through the humiliations it repeated in early 21st century, Foreigners took over the country in both cases. Public Domain

Finally, the madness of US foreign policy became explicit in 2010-2020. Like the fourth crusaders, American and European diplomats / economists used the insulting and colonizing mechanisms of the debt of Greece, 2010-2020, to weaken the country to the point of almost submission to the outrageous demands of Turkey, which “appears to be pursuing what it calls “Blue Homeland,” an expansionist strategy to claim waters and resources in the eastern Mediterranean and Aegean controlled by Greece and other countries. The plan envisions Turkey taking over several Greek islands where hundreds of thousands of Greek citizens live. While Greece may agree to take disputes regarding claims in the southeastern Mediterranean to international arbitration in The Hague, it will not negotiate about the Aegean.”

In 2024, the president of Turkey Erdogan recited his public relations lessons. He started with the understanding of the “good neighbor” talks with the Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis while he kept talking about the Greek Aegean as his blue homeland. Erdogan also supervised military exercises on how to capture Greek islands. In addition, Turkish warships appear whenever Greece tries to connect with Cyprus through underwater cables as it happened near the island of Kasos in November 2024 and Crete on February 8, 2025. A Greek reporter said, “The incident [in Crete], along with Turkey’s persistent interference in undersea cable surveys near Kasos, reflects a broader strategy of contesting Greek maritime activities, defying the spirit of the Athens Declaration meant to ease Aegean tensions… Ankara has consistently opposed Greece’s efforts to exercise its maritime rights, notably in the designation of marine parks, a process repeatedly altered under pressure. Similarly, Greece’s decision to limit offshore wind farm developments within its 6-nautical mile territorial waters reveals an attempt to avoid escalating disputes with Turkey. These measures highlight Athens’ delicate balancing act between asserting sovereignty and maintaining regional stability.”

But, of course, behind this nice diplomatic narrative, there’s fear, cowardliness and foreign influence that feeds the Turkish leaders of genocide. These invisible but real partners of Turkey, NATO, want desperately Turkey to remain in NATO. The price is Greek sovereignty and Syria.

You would think that the piratical practices of Turkey in the Greek Aegean would bring swift reaction on the part of Greece and the European Union. Greece is one of the states making up the EU. But neither Greece nor EU react to Turkish aggression. Perhaps both remember that the big brother, the United States, considers Turkey an “important ally.”

Conclusions

Nevertheless, the US, France and the European Union should be up in arms over such aggressive and destabilizing Turkish policy. But, no, the Imian neutrality and deception prevails. These powers see clearly what the Turks have in mind, and, silently, for reasons of expediency and strategic American hegemony, they bury the truth and sacrifice Greece.

Today they probably say to each other, Greece deserves the humiliations from Turkey. After all, Greece is no more than an archaeological park and tourism oasis. The country produces practically nothing for export. It willfully deindustrialized itself while it started borrowing more than it could ever repay back. Its corrupt leaders abandoned democracy for a foreign-imported scheme of democratic illusions. The Greek prime minister is running the executive, legislative and justice departments. He is a king. That prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, shamefully pretends to solve the problems Turkey is daily raising in the Aegean while the Turkish president Erdogan is provoking Greece with warships and violations of Greek sovereignty. Foreigners and Greek allies see these contradictions and side with Turkey. Greeks themselves, they say, talk to their enemies supposedly to improve their neighborhood while Turkey, a vociferous and millennial enemy of the Greeks, is digging their grave in front of their eyes. They should be shooting the Turkish vessels fishing and extracting other resources in Greek waters. But they always back off, which makes the Turks even more demanding for the capture of the Aegean. And the other perplexing reality is that Greece has been stronger in the air, what with super airplanes they have purchased from the US and France. But despite such a superiority, they don’t dare to face the Turks in the air or the sea. So, why are they arming themselves? To please France and the US for buying their arms? Or, perhaps, they buy American promises of preventing a Turkish attack on their country? But those promises, if they exist, are worthless. The Imia crisis made that crystal clear. And now with Donald Trump back in power, things are bound to be even more difficult. “Trump and his MAGA movement have fully internalized the morality of the ends justifying the means.”

I have repeatedly said that just like in ancient times, Greece in modern times must be self-reliant not merely in food but in weapons for defense, weapons the Greeks must construct at home. Spend the billions they borrow to strengthen their armed forces by utilizing an extraordinary engineering power the country possesses. Put those engineers at work at home to manufacture all that the country needs to defend itself. Second, reform the education in Greece, make it Hellenic. Give the students the knowledge to read and understand ancient Greek. Teach them ancient Greek literature, philosophy, and science in order to understand ancient and modern civilization as well as that they are descended from the people who invented science, classical art, democracy, the Parthenon, the Antikythera computer of genius, the theater, the Olympics, libraries and universities; poets like Homer, Hesiod, Aeschylos, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes; military leaders like Alexander the Great; philosophers like Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes, Heraclitos, Pythagoras, Plato and Aristotle; scientists like Hippocrates, Democritos, Aristarchos of Samos, Euclid, Ktesibios, Archimedes, Hipparchos, Apollonios of Perga and Ptolemaios and Galen; heroes like Herakles.

Then the Turks will start minding their own business.

Atatürk’s Ankara

This is the twelvth part in a series about riding night trains across Europe and the Near East to Armenia—to spend time in worlds beyond the pathological obsessions of Donald Trump. (This week newly installed President Elon Musk and his social media spokesman, Donald Trump, did their best to furlough most of the federal government, including everyone working for US AID, the FBI, CIA, and Department of Education.)

Mustafa Kemal (also known as Atatürk), second from the left in black tie, wanted Turkey (the 1923 successor of the Ottoman Empire) to be both a secular state and to remain a power in the muslim world—an inherent contradiction. Photo of a museum photo by Matthew Stevenson.

Close to the Ankara train station and my hotel was the Museum of the Republic. Just up the street was a second, similar museum dedicated to the War of Independence in 1923. Both were in buildings that housed the Turkish parliament in the early days of the republic, the successor state to the Ottoman Empire.

Under the terms of the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres—complimentary to the Treaty of Versailles and others signed in Paris after World War I—the Ottoman Empire was divided into zones of Allied occupation: Britain (and an international contingent) got Çanakkale and the Straits; Italy controlled Antalya and southern Turkey; France occupied eastern Turkey north of Syria; and Turkey itself was reduced to an area around Ankara. (The United States refused to take up a mandate over Armenia.)

No sooner was the Ottoman Empire partitioned than Greece invaded east from its zone of occupation around Izmir (then Smyrna), which touched off the conflict that became known as the Turkish war of independence. (It could be argued that it is still being fought to this day, especially in Kurdistan and Syria, if not in Gaza.)

+++

Led by Mustafa Kemal (aka Atatürk, which means “Father of the Turks”), the Turkish army fought from just outside Ankara all the way to the Mediterranean coast, culminating in the 1922 battle of Smyrna, which saw thousands of Greeks massacred on the waterfront (the number of victims varies from about 10,000 to 100,000) and ended the “Ionian visions” that Greater Greece would include ancient Greek cities in Anatolia.

In The Ottoman Endgame: War, Revolution and the Making of the Modern Middle East, 1908-1923 (which I had with me on my Kindle), historian Sean McMeekin writes:

Whoever actually started the great fire of Smyrna, it seems clear that many Turks saw it as poetic justice for the dozens of cities and towns the Greeks had put to the flames farther inland. For the fact remains that, even if many Turks lost property and a few mosques in the old city were burned, it was the Christians of Smyrna, Ottoman and European alike, who lost everything. What perished alongside the old city of Smyrna in September 1922 was the very idea that Greeks and Turks, Christians and Muslims, could live together peacefully in Asia Minor—or in mainland Greece, for that matter.

After their defeat in Smyrna, hundreds of thousands of Greeks living in Asia Minor fled to the state we think of as Greece, and after the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne re-drew the demarcation lines of the Treaty of Sèvres, Turkey declared its independence and republic, with Atatürk as its founding president. He had been the general in charge of defeating the Greeks in western Anatolia, just as, when he was a more junior officer, he had led the counterattacks at Gallipoli when the Allies tried to capture the Dardanelles in 1915.

Many museums in Ankara and Turkey are little more than exhibitions on the life and times of Mustafa Kemal; the Museum of the Republic has a display cabinet showing off his top hat and tails (he liked western formal wear).

+++

If the Museum of the Republic is devoted to early parliamentary procedures and Atatürk’s greatness as a politician, the Museum of the War of Independence (just up the road and on the corner of a busy intersection in old Ankara) is more concerned with his brilliance as a military commander.

In those displays cases, there are maps, flags, daggers, and pistols devoted to the cause of independence, which, in effect, was fought from 1914, when the Ottoman Empire (then on its last legs) decided to enter World War I on the side of the German allies.

In the two years previous to the Great War, in the two Balkan Wars (1912-13), the Ottoman Empire had largely been evicted from the European mainland. (It kept a rump presence near Edirne and the Bosphorus Straits.)

Then in World War I, the western Allies (France, Britain, and Russia) did their best to dismember the empire once referred to as the “sick man of Europe.” The British and French fought on sea and land at Gallipoli throughout much of 1915, eventually withdrawing in defeat at the end of the year. In Egypt and Palestine from 1916-18, largely British forces—including the camel corps in which T. E. Lawrence (of Arabia) often rode—attacked toward Jerusalem, Damascus, and the Hejaz Railway, which all fell in 1918.

Britain also sent an army up the Euphrates River in Mesopotamia against Ottoman forces, although they were surrounded and annihilated at Kut. Finally, Russian forces in World War I attacked from the Caucasus into eastern Turkey, besieging Kars and capturing the strategic city of Erzurum (to which I was headed).

In the midst of all these campaigns, the Ottoman leadership vented its rage against Armenian citizens of the empire, which led to the deaths (on forced marches or through starvations and beatings) of more than a million Armenians (the survivors were scattered into the Caucasus and Asia Minor). And it was to make sense of this sweep of history—especially from Anatolia to Erzurum and Kars—that I was now biking around Ankara and buying a railway ticket on the Dogu Express to eastern Turkey.

+++

From the Museum of the War of Independence, I biked up a short, steep hill to the Ulus Victory Monument, a statue of Atatürk on horseback, symbolically leading the nation to victory and independence. Then I set out on a bike ride that could only be considered folly.

I had a map in my pocket that showed “key sights” around Ankara, and I had GPS on my phone, which was clamped to my bicycle handlebars. But nothing prepared me for the absurdity of an Ankara bike ride, in which I found myself riding on broken sidewalks or standing at busy intersections trying to push the bike across the street.

I had ridden the same bicycle in New York, Moscow, London, Rome, and Saigon, and despite some learning curves I had managed to master the navigation through serious traffic. But here in Ankara I was defeated.

Most roads I headed down were clogged with cars, buses, and trucks, and even side streets that felt like death alleys. I went this way and that, searching for something like a bus lane in which I could ride, but came up with nothing.

After about an hour of such futility (add in a few steep hills to match), I gave up and rode back to my hotel, considering whether I might not even take the bike the following day, when I had planned to ride to Atatürk’s presidential home, now a museum on the outskirts of the metropolis. To use an expression from the Tour de France, I was thinking of “putting my foot on the ground,” an unpleasant consideration for any cyclist.

+++

I never left the hotel that evening (Ankara isn’t much of a city for pedestrians, but it does have sidewalks), and I spent much of my time after dinner with various city maps unfolded on my bed, trying to make sense of my possible ride the next day. As best I could tell, Atatürk’s house museum was about five miles from my hotel, on the far side of the Turkish State Cemetery and more war memorials.

On my phone and computer, I calculated various routes, and in the end, after a good night’s sleep, I came to the decision that I would start out on the bike and only give up if the traffic was unbearable. A full hotel breakfast further fortified me, and encouragement from the hotel staff (which by this point had warmed to the folding bicycle as a symbol of American eccentricity) made me think I might be able to succeed.

Once I got away from the small, crowded streets around my hotel, I rode along a wide boulevard, which in a few sections even had what looked like bicycle paths. The ride was uphill, but not steep, and I settled into the rhythm of watching both GPS on my phone and my lane for errant cars.

Beyond the the city downtown, I even began to enjoy the ride, although in a few places I found myself confused about the GPS directions, which forced me to hand-carry the bike across broad boulevards with a concrete meridians.

Eventually, following GPS, I turned right off the main boulevard and started riding on a wide, but strangely empty boulevard that, I soon discovered, was laced with police roadblocks and checkpoints.

By this point I was on an official bike lane, so I decided to press on, as Atatürk’s house was only a mile or so from my tracked location. It would have been a shame, after all this riding, if I had start again or find some other path through Ankara’s concrete wilderness.

At the very worst, I figured, the police would stop me from carrying on, but at the first checkpoint an officer cheerfully waved me on. Surely, I said to myself, all this security wasn’t for the protection of the house where Atatürk lived when he was the Turkish president from 1923 – 1938.

+++

Only when I biked to the top of the long incline did it dawn on me that I was riding on the (blocked) boulevard that led directly to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s “Presidential Complex,” his 300,000 square meter mansion that cost more than $600 million to build.

For years I had been reading about the building, but had no idea where in Ankara it was until I got to a second police barrier and checkpoint just opposite the main gates. Strangely, even at this checkpoint I was waved on, as if the Turkish president was expecting someone on a bike.

As much as I wanted to stop and take a picture of the building, I didn’t want to take out my phone, especially as at the top of the hill (opposite the main gates) there was a platoon of police soldiers keeping an eye on things. There was also a memorial to the failed 2015 coup in the plaza near the front gate, so I asked one of the policemen if he would take my picture in front of the monument.

If pictures were not allowed, he would say so, and if pictures were questionable I would rather say later that it was a police officer who had taken mine. Then I stood in front of the coup memorial in such a way that when the policeman took my picture, he would get the palace complex in the background, which is what happened.

Looking past the memorial at the front of the presidential mansion, I wondered whether this building was larger than Nicolae Ceaușescu’s Palace of Parliament. Both buildings seemed to have about 300,000 square meters and more than 1,000 rooms, and both seemed designed to house a government under siege, should things come to that (as they did for Ceaușescu, although when those bells tolled, his edifice complex was still evolving).

I later read that Erdoğan’s MacMansion has a library with 5 million books, fully functioning health clinic, nearby mosque, and full-service bomb shelter, which he needed in 2015, when insurrectionists attacked Erdoğan’s palace from the air. (He survived.)

The Ceaușescu manse, carved from stone, resembles an Orwellian ministry of fear, while Erdoğan’s residence looks more like the headquarters of a regional insurance company near Phoenix. Both speak to a government of pharaohs.

No comments:

Post a Comment