But what exactly is up for grabs?

Bloomberg News | February 18, 2025 |

Ukraine’s mineral wealth has been thrown into the spotlight as US President Donald Trump looks to seize control of its resources in return for military support. Yet very little is actually known about what’s up for grabs.

Various reports have suggested that Ukraine has mineral deposits worth upwards of $10 trillion, and President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s government has been keen to promote crucial materials that can be exploited as it seeks more military and economic support.

Rare earth elements — which play a key role in defense and other high-tech industries — have become a particular focus for Trump as he seeks to secure supplies of critical minerals. The President said last week he wanted the equivalent of $500 billion worth of rare earth.

But Ukraine has no major rare earth reserves that have been internationally recognized as economically viable. While the country has reported a series of deposits, little is known about their potential — most of them appear to be by-products of producing materials like phosphates, while some are in areas of Russian control.

“Rare earths are so niche that they typically don’t produce the more detailed studies publicly, so there’s just not enough information,” said Willis Thomas, principal consultant at CRU Group.

The market for rare earths — which are mainly used in high-strength magnets — is minuscule compared with commodities like copper or oil. The numbers are still small even if other key specialty minerals found in Ukraine are added to the mix: Last year, the US imported about $1.5 billion of rare earths, titanium, zirconium, graphite and lithium combined, according to Bloomberg calculations based on data from the US Geological Survey.

Information on Ukraine’s rare earth deposits have primarily been drawn from government data, and even the former head of the country’s geological survey said that there had been no modern assessment of the countries resources, S&P Global reported last week.

Even if Ukraine does have any economically viable deposits, the West still has a bigger challenge to overcome — mining them is relatively easy, but processing the raw material is much harder.

China accounts for roughly 60% of mined supply, but crucially about 90% of separation and refining capacity. Beijing has also flexed its muscles in recent years as tensions ratcheted up with the US over access to semiconductors.

Any deal with Ukraine “doesn’t really solve that pain point,” Thomas said. The US “still needs to have a value chain that is primarily ex-China that is separation and magnet making and this simply doesn’t exist at this point.”

Western miners have largely failed to build their own rare-earth businesses, stifled by environmental issues, processing challenges, extreme price volatility and the difficulties in competing with Chinese producers.

For example, Australia’s Lynas Rare Earths Ltd., one of the few producers outside of China, has been dogged by concerns over radioactive waste and community opposition to a processing plant in Malaysia.

In the US, Molycorp Inc. dominated the industry there before collapsing. Its successor MP Materials Corp., which operates the Mountain Pass project in California, was criticized in the past for sending raw materials to be processed in China. Washington has provided funding to both Lynas and MP to develop processing in the US.

How rare?

Like many critical minerals, rare earths are relatively abundant globally, but don’t often exist in large enough concentrations to be extracted and refined economically. Outside of China, the largest reserves are found in Brazil, India, Australia, Russia, Vietnam, and the US, according to the USGS.

Rare earths play a key role in defense and other high-tech industries, being used in everything from iPhones to laser-guided missiles. A F-35 fighter jet requires more than 900 pounds of rare earth elements, while each Virginia-class nuclear submarine contains 9,200 pounds, according to the US Defense Department.

Ukraine had not received much interest before Russia’s full-scale invasion from the world’s biggest mining companies, who’ve spent much of the last two decades scouring the globe for untapped metal deposits.

The country’s main established miner is Ferrexpo Plc, a London-listed iron ore company that produces some of the highest grade pellets used to make steel. Steelmaker Metinvest BV mines coal and iron ore. The country also produces uranium.

Trump’s interest

Trump has made securing resources for the US and tackling China’s dominance of certain raw materials a cornerstone of his foreign policy so far. He has targeted Panama over access to its crucial waterway, homed in on Greenland’s mineral riches — mooting a potential takeover of the Danish territory — and now linked securing Ukraine’s resources as a key part of ongoing support in its war with Russia.

Ukraine has also been keen to promote its lithium, graphite and titanium deposits.

The country says it has the Europe’s biggest deposit of lithium, a material that is abundant around the world. Demand has surged because of its crucial use in rechargeable batteries, but production has risen far ahead of demand and prices have crashed in recent years.

In the case of titanium, Ukraine isn’t necessarily producing the form that America’s defense industry needs. Ukraine is a top-ten producer of two titanium-bearing minerals called ilmenite and rutile, and in the US, 95% of those materials are used to make a common white pigment. Ukraine has no capacity to produce titanium sponge, the form of the metal used in jet engines, armor plating, and other defense applications, according to USGS data.

“Titanium, the ilmenite and rutile, the main raw materials there, they’re found across the world and it’s really about ease of extraction, ease of processing and how easily it is shipped,” said Thomas.

(By Thomas Biesheuvel and Mark Burton)

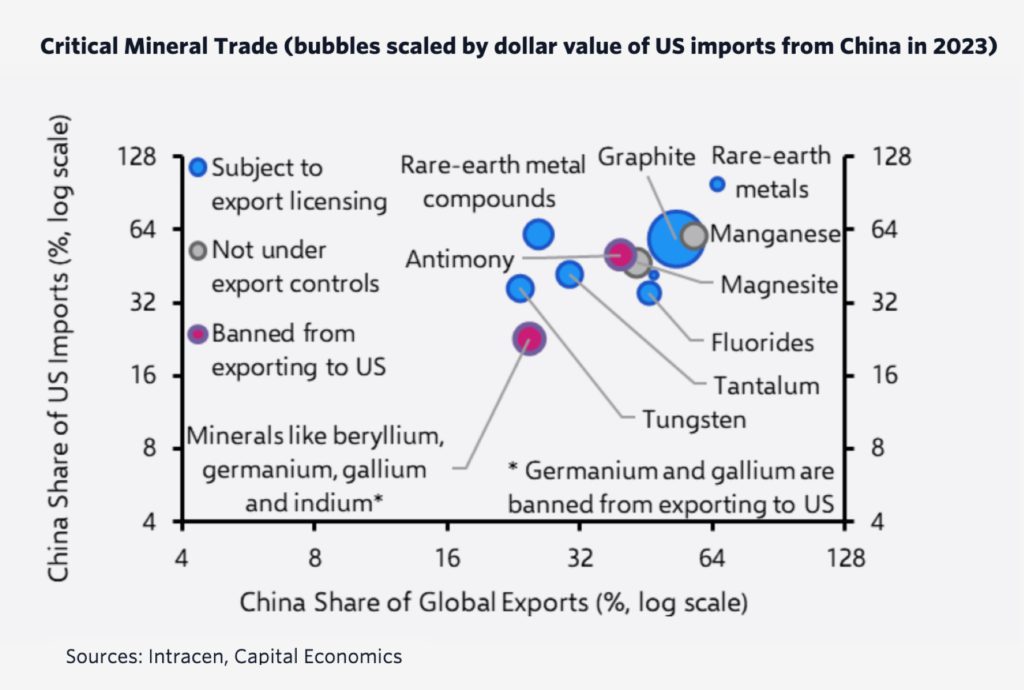

GRAPH: The critical minerals to watch in the US

Frik Els | February 17, 2025 |

Another arrow in the quiver. Baotou City: Epicentre of China’s rare earth industry.

Image by Matthew Stinson Creative Commons CC BY-NC 2.0

Statements that Trump’s plans to make Canada the 51st state is all about metals and minerals, a deal for Ukraine’s rare earths (now rejected) being included in peace talks, and the current US administration reiterating its desire to buy Greenland, have thrust critical minerals into the public view like never before.

Amid all this talk it’s easy to forget that anything to do with metals and minerals – whether deemed critical or not – is really about one country. China.

China unveiled a series of retaliatory measures against new US tariffs a fortnight ago, including restrictions on the export of tungsten, tellurium, bismuth, indium, and molybdenum, stating that export licenses will only be granted to companies complying with “relevant regulations.”

These measures fall short of the mineral export bans that China imposed on the US in December, which included gallium, germanium, antimony, and so-called superhard materials.

Antimony prices outside China have doubled this year while bismuth, even in the absence of an outright ban, has shot up to a decade-high.

Graphite is used in virtually all electric vehicle and energy storage batteries and Beijing’s tightening of export rules around graphite late last year could have bigger impacts. China dominates global production, and to an even greater extent, processing of the anode material.

The rules in effect around graphite are similar to those applied to rare earths in 2023, but so far Chinese supply of rare earth metals and magnets to the rest of the world has been ample and prices are subdued inside and outside the country.

More than a decade ago China’s imposition of export quotas saw rare earth prices skyrocket with, for example, dysprosium going from $118/kg to $2,262/kg between 2008 and 2011. China ended up in front of a WTO tribunal in 2010 and the industry calmed down.

While rare earth exploration and production outside China have boomed since then, the country’s grip on downstream permanent magnet and rare earth metal production will take many more years to fully prise.

While a relatively small market at the mining level, rare earth metals and magnets are used in the vast majority of EV motors and the 17 elements feed into a variety of high-tech industries including robotics, defence and aerospace.

Statements that Trump’s plans to make Canada the 51st state is all about metals and minerals, a deal for Ukraine’s rare earths (now rejected) being included in peace talks, and the current US administration reiterating its desire to buy Greenland, have thrust critical minerals into the public view like never before.

Amid all this talk it’s easy to forget that anything to do with metals and minerals – whether deemed critical or not – is really about one country. China.

China unveiled a series of retaliatory measures against new US tariffs a fortnight ago, including restrictions on the export of tungsten, tellurium, bismuth, indium, and molybdenum, stating that export licenses will only be granted to companies complying with “relevant regulations.”

These measures fall short of the mineral export bans that China imposed on the US in December, which included gallium, germanium, antimony, and so-called superhard materials.

Antimony prices outside China have doubled this year while bismuth, even in the absence of an outright ban, has shot up to a decade-high.

Graphite is used in virtually all electric vehicle and energy storage batteries and Beijing’s tightening of export rules around graphite late last year could have bigger impacts. China dominates global production, and to an even greater extent, processing of the anode material.

The rules in effect around graphite are similar to those applied to rare earths in 2023, but so far Chinese supply of rare earth metals and magnets to the rest of the world has been ample and prices are subdued inside and outside the country.

More than a decade ago China’s imposition of export quotas saw rare earth prices skyrocket with, for example, dysprosium going from $118/kg to $2,262/kg between 2008 and 2011. China ended up in front of a WTO tribunal in 2010 and the industry calmed down.

While rare earth exploration and production outside China have boomed since then, the country’s grip on downstream permanent magnet and rare earth metal production will take many more years to fully prise.

While a relatively small market at the mining level, rare earth metals and magnets are used in the vast majority of EV motors and the 17 elements feed into a variety of high-tech industries including robotics, defence and aerospace.

Source: Capital Economics

China is dealing with its own rare earth problems with the collapse of imports from Myanmar, the country’s main source of particularly heavy rare earths, after rebel forces seized the country’s main producing region on the Chinese border. The turmoil has already led to higher REE prices.

Though there are no bans on graphite and rare earths exports, it’s a shot across the bow, and allows Beijing to keep its powder dry, for any future retaliation against US trade sanctions.

In a note, Capital Economics points out that the targeted goods in China’s latest round represent just $2 billion in annual exports – well below 0.1% of China’s total exports:

“But it adds to a growing arsenal of export controls that Beijing can use to throttle foreign access to key inputs. Around 9% of Chinese exports, including most of its shipments of critical minerals, are now subject to export licensing requirements.”

China is dealing with its own rare earth problems with the collapse of imports from Myanmar, the country’s main source of particularly heavy rare earths, after rebel forces seized the country’s main producing region on the Chinese border. The turmoil has already led to higher REE prices.

Though there are no bans on graphite and rare earths exports, it’s a shot across the bow, and allows Beijing to keep its powder dry, for any future retaliation against US trade sanctions.

In a note, Capital Economics points out that the targeted goods in China’s latest round represent just $2 billion in annual exports – well below 0.1% of China’s total exports:

“But it adds to a growing arsenal of export controls that Beijing can use to throttle foreign access to key inputs. Around 9% of Chinese exports, including most of its shipments of critical minerals, are now subject to export licensing requirements.”

Ukraine Rejects Trump’s Proposal for Mineral Rights

By Alex Kimani - Feb 17, 2025

Zelenskyy is seeking stronger security guarantees from the U.S. in exchange for any potential agreements regarding Ukraine's mineral resources.

This rejection highlights the ongoing tensions between Ukraine and the U.S. over the terms of future cooperation.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has declined a proposal by U.S. President Donald Trump to acquire approximately 50% of Ukraine’s rare earth mineral rights. Valued at several trillion dollars, Ukraine’s mineral reserves include lithium, titanium, and graphite which are essential for high-tech industries. The proposal was delivered by U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent as part of a bid to compensate Washington for assistance to Kyiv. Trump had suggested that Ukraine owed the United States $500 billion worth of resources for its past military support.

However, Zelenskyy is seeking better terms, including U.S. and European security guarantees. Trump’s proposal did not include provisions for future assistance, which Zelenskyy deems necessary. Zelenskyy’s team has developed an offer for a mineral partnership in exchange for security guarantees, which was announced earlier this month.

The EU has floated the idea of resuming purchases of Russian pipeline gas as part of a potential settlement of the Russia-Ukraine war. Backed by Hungarian and German officials, the proposal argues that the move could give both Russia and Europe incentives to maintain a peace deal while stabilizing the continent's energy market.

Last month, Slovakia’s Prime Minister Robert Fico revealed that he’s not ruling out the resumption of gas through Ukraine following the expiration of a 5-year transit deal between Moscow and Kyiv. Fico has been pushing President Volodymyr Zelenskiy to restart the transit, citing higher energy costs for Slovakia and the whole region.

‘‘The pipeline that runs through Slovakia has a capacity of 100 billion cubic meters,” Fico told reporters in Brussels on Thursday. “I want to do everything to ensure it is used in the future,’’ he added.

Europe’s vast natural gas inventories are currently depleting at the fastest clip since 2018 as cold weather ramps up heating needs. According to Gas Infrastructure Europe data, Europe’s gas storage was only 49% full on February 10, well below last year's 67% mark at a corresponding point and the 10-year average of 51% for the same period. The continent’s seasonal draw has been bigger than in the previous two winters due to colder weather, lower wind power generation due to low wind speeds and the termination of Russian gas imports via Ukraine. The situation is even more dire in Germany, Europe’s largest economy, with its underground sites currently only 48% full, a significant decrease from the 72% recorded at the same time last year.

By Alex Kimani for Oilprice.com

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has rejected a U.S. proposal to acquire a significant stake in Ukraine's mineral resources.

Zelenskyy is seeking stronger security guarantees from the U.S. in exchange for any potential agreements regarding Ukraine's mineral resources.

This rejection highlights the ongoing tensions between Ukraine and the U.S. over the terms of future cooperation.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has declined a proposal by U.S. President Donald Trump to acquire approximately 50% of Ukraine’s rare earth mineral rights. Valued at several trillion dollars, Ukraine’s mineral reserves include lithium, titanium, and graphite which are essential for high-tech industries. The proposal was delivered by U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent as part of a bid to compensate Washington for assistance to Kyiv. Trump had suggested that Ukraine owed the United States $500 billion worth of resources for its past military support.

However, Zelenskyy is seeking better terms, including U.S. and European security guarantees. Trump’s proposal did not include provisions for future assistance, which Zelenskyy deems necessary. Zelenskyy’s team has developed an offer for a mineral partnership in exchange for security guarantees, which was announced earlier this month.

The EU has floated the idea of resuming purchases of Russian pipeline gas as part of a potential settlement of the Russia-Ukraine war. Backed by Hungarian and German officials, the proposal argues that the move could give both Russia and Europe incentives to maintain a peace deal while stabilizing the continent's energy market.

Last month, Slovakia’s Prime Minister Robert Fico revealed that he’s not ruling out the resumption of gas through Ukraine following the expiration of a 5-year transit deal between Moscow and Kyiv. Fico has been pushing President Volodymyr Zelenskiy to restart the transit, citing higher energy costs for Slovakia and the whole region.

‘‘The pipeline that runs through Slovakia has a capacity of 100 billion cubic meters,” Fico told reporters in Brussels on Thursday. “I want to do everything to ensure it is used in the future,’’ he added.

Europe’s vast natural gas inventories are currently depleting at the fastest clip since 2018 as cold weather ramps up heating needs. According to Gas Infrastructure Europe data, Europe’s gas storage was only 49% full on February 10, well below last year's 67% mark at a corresponding point and the 10-year average of 51% for the same period. The continent’s seasonal draw has been bigger than in the previous two winters due to colder weather, lower wind power generation due to low wind speeds and the termination of Russian gas imports via Ukraine. The situation is even more dire in Germany, Europe’s largest economy, with its underground sites currently only 48% full, a significant decrease from the 72% recorded at the same time last year.

By Alex Kimani for Oilprice.com

Ukraine's Critical Minerals and the Path to Peace

The US is interested in Ukraine's large reserves of rare earth minerals as part of a potential peace agreement.

Ukraine holds significant deposits of strategic materials, including titanium, graphite, and lithium, which are valuable for various industries.

The US aims to secure these minerals to reduce its reliance on China for critical resources.

Ukrainians are learning the transactional nature of the Trump administration as the US president revealed a “critical” (pun intended) part of his plan for ending the three-year old conflict.

Media reports say that Scott Bessent, the US treasury secretary, met with Ukrainian President Zelensky on Feb. 12. The two discussed a minerals deal between Kyiv and Washington that would provide Ukraine with a post-war “security shield”.

At stake are $500 billion in rare earth minerals that Trump wants before offering a security guarantee from Washington.

Bessent said the minerals deal is part of a “larger peace deal that Trump has in mind”. Zelensky told reporters on Wednesday that the United States presented Ukraine with a first draft agreement he hoped could seal a deal at the February 14-16 Munich Security Conference.

“We had a productive, constructive conversation. For me, the issue of security guarantees for Ukraine is very important, and we talked about minerals in general,” said Zelensky, via Reuters.

Trump has said he wants a rapid end to the war between Ukraine and Russia but has not made clear whether he will continue vital military aid to Ukraine that was a cornerstone of President Biden’s foreign policy.

According to Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty, Trump spoke directly with Russian President Putin on Feb. 12 for more than an hour, agreeing to begin peace negotiations.

According to the Ukrainian Geological Survey, Ukraine holds 23 of the 50 strategic materials identified by the US as critical, and 26 out of the 34 recognized by the EU as critically important. Particularly, Ukraine holds competitive positions in titanium, graphite, lithium, beryllium, and rare earth elements.

There are currently 30 licenses issued for the development of this group of minerals. The Ukraine government holds over 30 unlicensed deposits and about 400 promising occurrences. It also manages several important industrial assets capable of fabricating titanium, aluminum, silicon, germanium and gallium.

Titanium and beryllium are used in aerospace and defense, with Ukraine holding the largest titanium reserves in Europe.

The country has reserves of lithium and graphite — used in lithium-ion batteries needed for a plethora of uses including electric vehicles and renewable energy storage. Graphite is used in the battery’s anode.

However, no lithium is currently mined in Ukraine, with two of four potential sites located in Russian-occupied territory.

Ukraine can reportedly supply battery factories with natural graphite concentrate, with six known deposits, one of which is operated by Australia-headquartered Volt Resources. Licenses were issued for three more graphite deposits in 2019 and 2021.

The extraction of tantalum, niobium and rare earth elements is centered around the Novopoltava phosphate deposit and the Azov REE deposit — both of which are in occupied territory.

The United States currently only has one producing rare earths mine — Mountain Pass in California owned by MP Materials. Australia-based Lynas is building a rare earths processing facility in Seadrift, Texas. In 2023, Nasdaq-listed coal miner Romaco Resources announced initial development work on the Brook rare earths mine in Wyoming would start in the fourth quarter.

Along with large percentages of rare earth oxides, the mine may contain meaningful amounts of gallium and germanium — said Mining Weekly — used widely in semiconductors and defense systems. China controls the supply of both, and in July 2023 introduced new export controls, followed by a ban on exports to the US in December 2024.

China also controls more than 85 percent of the world’s rare earth processing capacity and mines most of the minerals. According to the US Geological Survey, China holds 44 million tonnes of reserves, more than double the nearest competitor Brazil, and compared to the United States’ 1.9 million tonnes.

Between 2020 and 2023, the US imported 70 percent of its rare earth metals and compounds from China.

By Andrew Topf for Oilprice.com

By Andrew Topf - Feb 16, 2025

The US is interested in Ukraine's large reserves of rare earth minerals as part of a potential peace agreement.

Ukraine holds significant deposits of strategic materials, including titanium, graphite, and lithium, which are valuable for various industries.

The US aims to secure these minerals to reduce its reliance on China for critical resources.

Ukrainians are learning the transactional nature of the Trump administration as the US president revealed a “critical” (pun intended) part of his plan for ending the three-year old conflict.

Media reports say that Scott Bessent, the US treasury secretary, met with Ukrainian President Zelensky on Feb. 12. The two discussed a minerals deal between Kyiv and Washington that would provide Ukraine with a post-war “security shield”.

At stake are $500 billion in rare earth minerals that Trump wants before offering a security guarantee from Washington.

Bessent said the minerals deal is part of a “larger peace deal that Trump has in mind”. Zelensky told reporters on Wednesday that the United States presented Ukraine with a first draft agreement he hoped could seal a deal at the February 14-16 Munich Security Conference.

“We had a productive, constructive conversation. For me, the issue of security guarantees for Ukraine is very important, and we talked about minerals in general,” said Zelensky, via Reuters.

Trump has said he wants a rapid end to the war between Ukraine and Russia but has not made clear whether he will continue vital military aid to Ukraine that was a cornerstone of President Biden’s foreign policy.

According to Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty, Trump spoke directly with Russian President Putin on Feb. 12 for more than an hour, agreeing to begin peace negotiations.

According to the Ukrainian Geological Survey, Ukraine holds 23 of the 50 strategic materials identified by the US as critical, and 26 out of the 34 recognized by the EU as critically important. Particularly, Ukraine holds competitive positions in titanium, graphite, lithium, beryllium, and rare earth elements.

There are currently 30 licenses issued for the development of this group of minerals. The Ukraine government holds over 30 unlicensed deposits and about 400 promising occurrences. It also manages several important industrial assets capable of fabricating titanium, aluminum, silicon, germanium and gallium.

Titanium and beryllium are used in aerospace and defense, with Ukraine holding the largest titanium reserves in Europe.

The country has reserves of lithium and graphite — used in lithium-ion batteries needed for a plethora of uses including electric vehicles and renewable energy storage. Graphite is used in the battery’s anode.

However, no lithium is currently mined in Ukraine, with two of four potential sites located in Russian-occupied territory.

Ukraine can reportedly supply battery factories with natural graphite concentrate, with six known deposits, one of which is operated by Australia-headquartered Volt Resources. Licenses were issued for three more graphite deposits in 2019 and 2021.

The extraction of tantalum, niobium and rare earth elements is centered around the Novopoltava phosphate deposit and the Azov REE deposit — both of which are in occupied territory.

The United States currently only has one producing rare earths mine — Mountain Pass in California owned by MP Materials. Australia-based Lynas is building a rare earths processing facility in Seadrift, Texas. In 2023, Nasdaq-listed coal miner Romaco Resources announced initial development work on the Brook rare earths mine in Wyoming would start in the fourth quarter.

Along with large percentages of rare earth oxides, the mine may contain meaningful amounts of gallium and germanium — said Mining Weekly — used widely in semiconductors and defense systems. China controls the supply of both, and in July 2023 introduced new export controls, followed by a ban on exports to the US in December 2024.

China also controls more than 85 percent of the world’s rare earth processing capacity and mines most of the minerals. According to the US Geological Survey, China holds 44 million tonnes of reserves, more than double the nearest competitor Brazil, and compared to the United States’ 1.9 million tonnes.

Between 2020 and 2023, the US imported 70 percent of its rare earth metals and compounds from China.

By Andrew Topf for Oilprice.com

No comments:

Post a Comment