A Conservative Group Offers a Radical Analysis of Climate Change

A recent report by the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA) presents a radically different perspective from that provided by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on the risks associated with global heating.

Adapting the standard methodologies that actuaries use to determine the solvency of banks, pension funds, insurance companies, and other critical financial institutions, the IFoA, the regulatory body for actuaries in the UK, applied their risk management expertise to assessing climate impacts. They worked with a group of earth scientists at the University of Exeter to expand their risk analysis beyond the financial to include ecological and social risks. They included this broader systemic approach because they explicitly acknowledged that the financial focus was much too narrow and ignored the role nature and social features contribute to economic activities.

They expanded the notion of financial solvency to explore what they call “planetary solvency,” the capacity of earth’s systems to maintain the biosphere on which all life depends.

They cite two reasons for integrating ecological and social dimensions into their risk management work. These dimensions can significantly impact economic activities, but current economic models exclude such considerations. For example, severe storms caused by global heating can disrupt supply chains for extended periods. The second reason is that social or ecological risks can rise to such catastrophic levels that economic activity becomes irrelevant. At some level of heating, humans cannot survive.

The report concludes: “The risk of Planetary Insolvency looms unless we act decisively. Without immediate policy action to change course, catastrophic or extreme impacts are eminently plausible, which could threaten future prosperity.”

The Function of Actuaries

Actuaries typically analyze financial risks to ensure that an institution can remain solvent and continue operating well into the future, despite the likely risks it will encounter along the way. Their analyses consider worst-case scenarios, even ones with low probability of occurrence, especially if the worst cases are extreme or catastrophic.

Actuaries use the concept of “risk appetite” to identify the level of acceptable risk, given that risks are often uncertain but inevitable. A very low level of risk tolerance is used to ensure that these financial institutions, upon which millions of people depend, are solvent.

For example, in Europe, the amount of capital that an insurance company is required to hold is set at a level designed to withstand an extreme loss scenario that would occur only once in 200 years. This is equivalent to no more than a 0.5 percent chance of becoming insolvent in any one year.

The IFoA report makes some important comments about the respective roles of science and risk management, and how they are different but complementary. The IPCC relies heavily on science rather than formal risk management approaches.

Science is essentially concerned with accurate measurement and identifying underlying laws of nature. The conservatism inherent in the scientific process, while possibly identifying extreme but uncertain risks, emphasizes the certainties that research can provide.

By contrast, risk management, based on information provided by science and expert perspectives, determines the level of risk associated with various scenarios, and the probability of those scenarios occurring. Risk management focuses on extreme risks, not out of doom and gloom, but to understand the circumstances that could give rise to such extremes, and thus come to understand how to avoid them. Risk management accepts uncertainty and provides a transparent means of dealing with it.

In order to keep the uncertainties associated with extreme risks to a minimum, actuaries conduct frequent reviews of risk levels as new information becomes available. They don’t wait for the certainties associated with science but use updated information to adjust their levels of risk tolerance.

Risk management methodologies can deal with uncertainties in a way that science does not. They provide decision makers with valuable insights regarding necessary actions to avoid catastrophic impacts. Waiting for the certainties that science can provide could easily be too late for the required action.

The risk management approach assists decision makers to determine the urgency of specific actions, whether to slam on the brakes when a child runs into the road, or to slow down at a pedestrian crossing.

Actuaries are not merchants of pessimism, but of prudence. They base their analyses on the highest estimate of economic loss and reduce that estimate only when evidence becomes available that it is over-stated. This is a much more precautionary approach than focusing on what is perceived as most likely. Prudence increases the likelihood of avoiding extreme or catastrophic impacts, even if they are uncertain.

The Actuarial Critique of the IPCC

The IFoA actuaries shift the focus from financial solvency to planetary solvency, asking how to avoid the breakdown of earth systems that provide humanity with all the resources needed to survive and thrive.

They thus critique the IPCC process from an actuarial perspective, concluding: “Global risk management practices for policymakers are inadequate, we have accepted much higher levels of risk than is broadly understood…..Unmitigated climate change and nature-driven risks have been hugely underestimated.”

One obvious example of this inadequate risk management from the IPCC is its setting of a carbon target that has only a 50 percent chance of keeping global heating below 1.5 degrees C. This is the level where several significant negative impacts are thought to accelerate.

This means that the IPCC has accepted a level of risk associated with climate breakdown that is 100 times higher than for European insurance companies going insolvent.

Furthermore, this carbon target was established in 2018 and has not been revised since, despite the now well-established increased heating and associated risks that have exceeded the conservative IPCC projections. The science-based projections are inherently conservative, and have consistently underestimated later measurements associated with global temperature increases, sea level rise, extreme events, ocean current changes, and ice melts.

Not only does the IPCC fail to conduct annual revisions of such critical goals, it also ignores several features of the science that are now well established. Multiple tipping points have been clearly identified and more research data regarding them are available. Tipping points define thresholds beyond which negative changes may be irreversible.

Unfortunately, tipping points are not included in the IPCC scenarios because there is still too much uncertainty associated with the precise thresholds for their occurrence and their severity from a strictly scientific perspective. More research is needed.

But the potential consequences of earth systems breaking down—planetary insolvency in risk management terms—is very real. The science does not deal with the uncertainty, but risk management methodology does.

Inclusion of the tipping points in the risk management approach allows for their interactions to be considered as well as their direct impacts. As the biosphere is an integrated whole, changes in one tipping point can easily cascade to other areas, resulting in catastrophic impacts.

The risk management approach also allows for the ecological tipping points to be considered in terms of their relationship to social and economic impacts. This has rarely been undertaken in narrow financial impact studies of climate change, resulting in gross underestimations of the economic impact of global heating.

The combined impact of these various tipping points is to lower the temperature at which extreme social and economic impacts may occur. The interplay of geopolitical tensions regarding resource or migration conflicts on climate impacts is also ignored in the IPCC process. The risk management approach can integrate these dynamics into its assessment.

Because risk management has reliable techniques for dealing with the inherent uncertainties associated with these extreme scenarios, they provide invaluable information for decision makers to take appropriate actions. But decision makers are not using these sophisticated risk management tools in the IPCC. It’s both ironic and terrifying that less comprehensive and prudent methodologies are used to evaluate the stability of the earth systems that underlie our entire wellbeing than are currently applied to pensions and insurance.

Better Risk Assessment

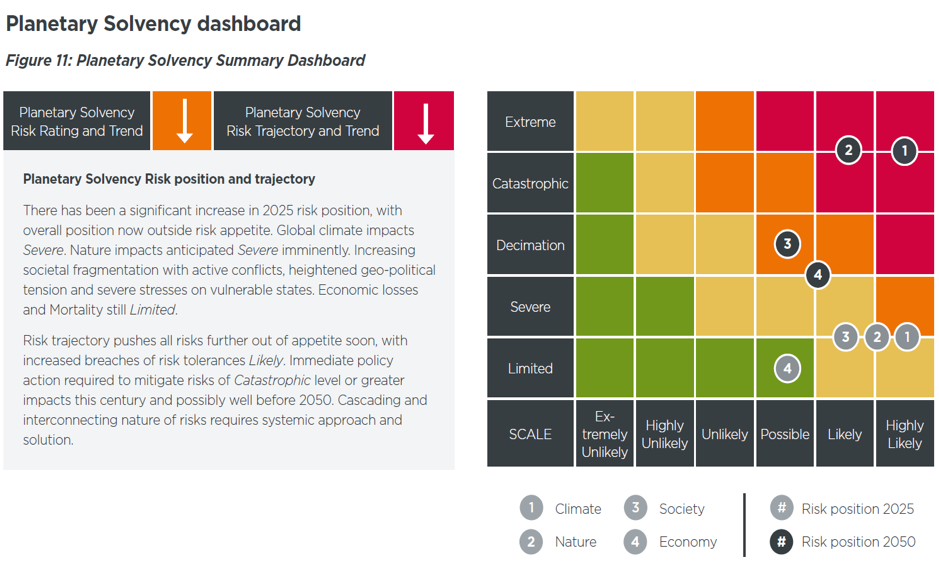

The IFoA team did an example exercise to indicate what a more appropriate risk assessment could provide. Their Planetary Solvency Dashboard indicates current risk levels for climate, nature, society and economy.

Their analysis indicates that the world is currently outside the risk tolerance (green space) for all areas other than Economy. And the situation projected for 2050 ranges from Decimation for Economy to Extreme or Catastrophic for all other areas.

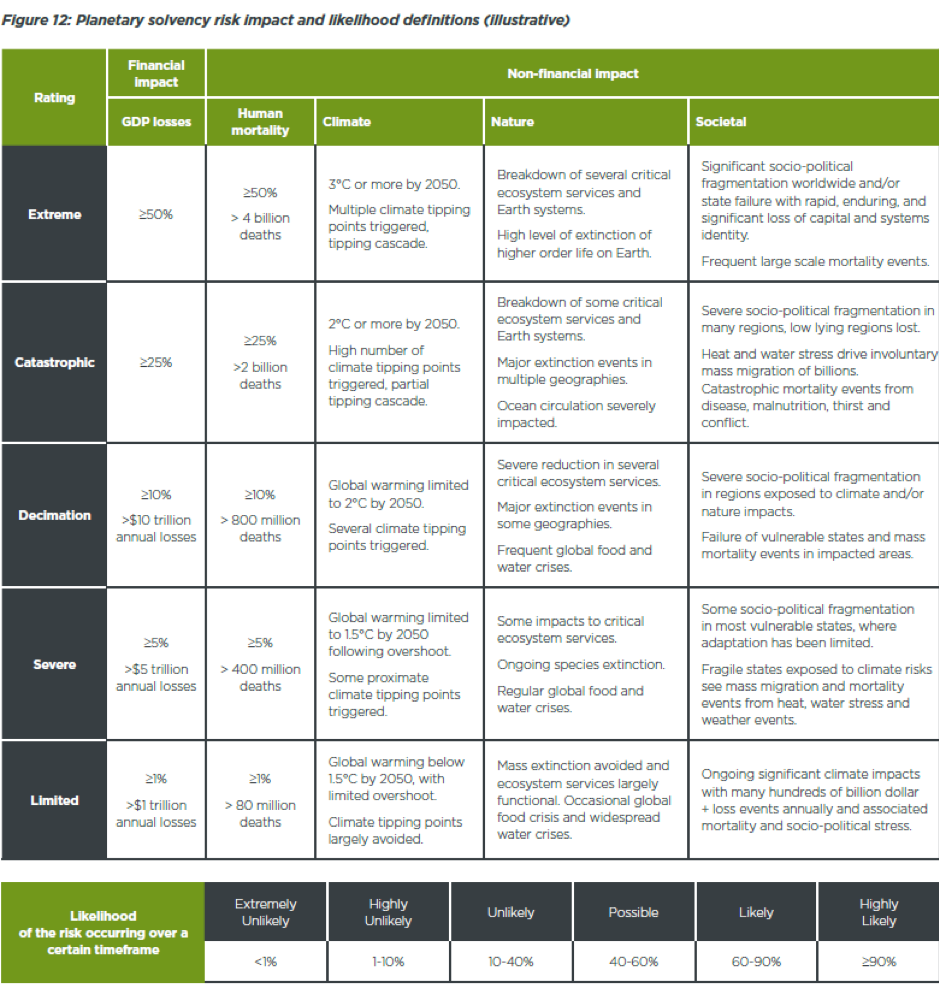

Relevant terms are defined in the next table. Note the 25% reduction in GDP associated with the Catastrophic designation.

The Planetary Solvency Dashboard describes a much more serious assessment of the financial, climate, ecological, and social risks than the ones that guide the IPCC and financial institutions. If banks, insurance companies, and pension funds paid heed to these Dashboard results, they would have to significantly reevaluate their current operations.

Given the urgency of the IFoA report, bank and pension fund investments in fossil fuels would have to shrink rapidly. Investments in any activities that are disrupting ecosystem services would also have to be significantly curtailed.

The implications of the Dashboard summary extend beyond the financial sector. Corporations reliant on fossil fuels—or whose operations cannot avoid disrupting natural systems, such as mining operations or land development of any kind—would also have to reexamine their future prospects to continue operating. They would have to justify, if possible, that their continued operation provided significant benefits to society that offset the biosphere disruption they cause. Otherwise, they would lose their social license to operate.

Adopting an actuarial approach to planetary solvency would also realign government priorities. Governments would have to provide the policy frameworks for companies operating within a safe climate space. Governments would also have to step up their efforts to support policies that alleviated the inevitable social challenges that are already evident. Migration, gross inequality, and population size all deserve considerably more effort and international cooperation to avoid the projected risks identified in the Dashboard analysis.

A wide range of international financial disclosure procedures would need to be upgraded to Planetary Solvency standards. These would include the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), the European Union Transparency Directive, the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS), and the requirements for listing on national stock exchanges, to name just a few. All of these institutions currently use levels of risk tolerance that grossly underestimate planetary solvency.

The Way Forward

The actuarial report identifies a number of actions to bring about a more realistic appraisal of our state of planetary solvency. Such information would ensure that decision makers in national and supra-national institutions, especially the UN Security Council, have the most comprehensive and useful information available.

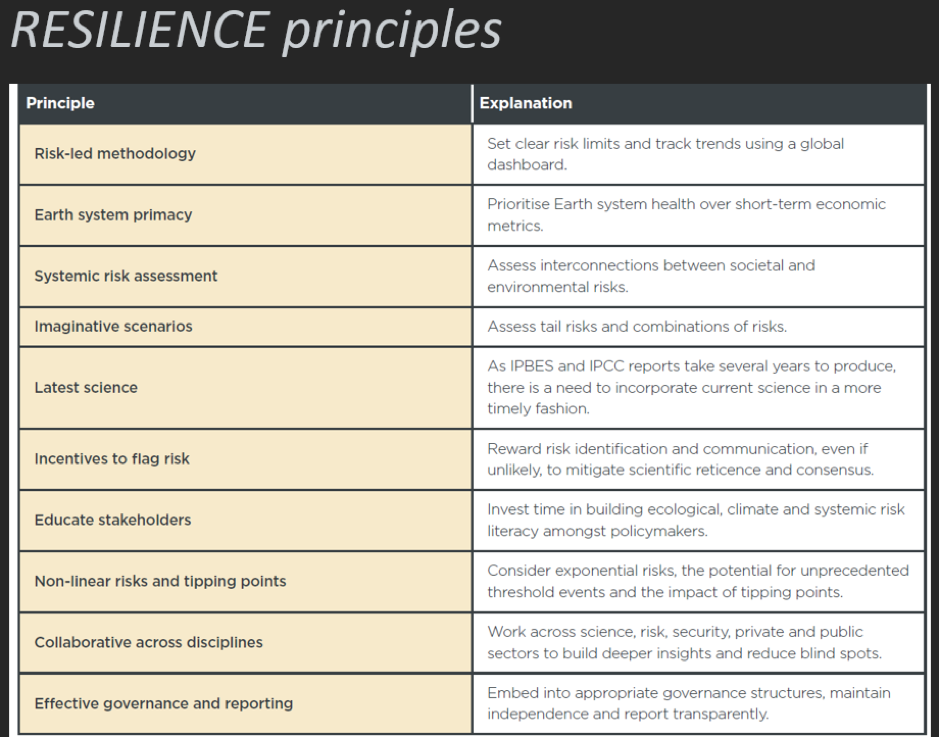

The actuaries recommend establishing an independent agency to provide annual Planetary Solvency assessment using the precautionary methodologies of risk management. They suggest updating financial solvency approaches with agreed-upon climate, ecological and social goals. And they propose a set of resilience principles that can act “as guidelines for effective civilisational risk management.”

The financially astute actuaries involved in this report state that the “current market-led approach to mitigating climate and nature risks is not delivering. There is an increasing risk of severe societal disruption (Planetary Insolvency), as our economic system drives further global warming and nature degradation.”

People everywhere trust actuaries with their pensions and investments. Perhaps it’s time to trust their expertise regarding the risks to earth systems as well.

In the autumn of 2014, I was sitting in a tiny shed at a writing residency in Point Reyes, Northern California. I was there to write my book about the psychology of facing planetary crises. One particularly warm afternoon, I was looking out at Tomales Bay, teeming with bird life, when my phone rang with an unknown Washington DC number.

Grateful for any distraction, I took the call.

The fast-talking man on the other end of the line introduced himself as a senior advisor to the Republican Party. Let’s call him “Bob” (not his real name). A seasoned messaging expert, Bob’s specialty was creating messaging for the party on hot-button issues — the kind that tend to fracture and polarize our collective conversations: healthcare, social security, tax reform, foreign policy. Then he’d brief senior members of the Republican Party on what he’d tested, based on extensive focus groups, interviews and live dial testing.

A conservative philanthropist — who, he quickly explained, wished to remain anonymous — had approached him for help in developing compelling messaging about tackling climate change… for conservatives. Who were also climate skeptics.

Bob, a lifelong Republican, confessed that he was feeling increasing anxiety and urgency about our global climate crisis, and he desperately wanted to help engage his party on the subject. This project felt like a way to address his existential dread by doing what he did very well: using finely honed research methods for crafting effective messaging strategies on tough topics, the most polarizing issues in our country.

The remit was daunting, however. He started asking around for guidance, and a number of people suggested I may be able to help. As a psychologist focused on cracking the code on climate action, he’d sought me out to help thread this particularly tricky needle.

After explaining the scope, he paused. Then he asked,”So, what do you think?”

I felt excited, surprised… and suspicious.

Even so, I asked when we could get started.

Even as it seems the U.S. is accelerating backwards on climate action, what if we are radically under-estimating our capacity for real social change? In recent days, I have been thinking a lot about this question, and the tools that I’m convinced can unlock what we may believe is unthinkable. Namely, moving from a “yell, tell and sell” theory of change, where people often shut down, turn away and deny, to one of guiding people with very different views towards taking steps to address climate change.

To do this, we have to be open to revising our own theories of change. We have to be able to listen and acknowledge what millions of people are feeling and saying: that we are confused, overwhelmed, scared, angry, and threatened. No amount of cheerleading, educating and ‘righting’ at people is going to change that. People respond neurologically to being heard, respected and yes, redirected to what is in our joint best interest. What I am describing is an evidence-based, scientifically sound approach to shifting mindsets, hearts and behaviors. It is also reflected in the fields of social neuroscience, relational psychology and motivational interviewing in the public health sector. As the psychiatrist Dr Daniel Siegel says, “name it to tame it.”

As a former academic psychosocial researcher-turned-practitioner, I had been applying my training to strategies for protecting and caring for our planet well before I received Bob’s call. It turns out that those years of in-depth training are very relevant for existential issues such as climate change, energy transition and environmental protection. Therefore, when Bob contacted me, I knew that his team would need to approach their research differently. These issues were charged, complex, scary, big and existential. I wanted to get beyond the usual trope in progressive circles that “people don’t care” or are simply ignorant.

We started with training the team on how to get past the party’s usual talking points, and focus instead on how voters were actually thinking and feeling about the issue. I guided them in the practice of attunement: being present, putting one’s own reactivity and agenda aside, and listening between the lines of what people are voicing. This approach, informed by trauma researchers, motivational interviewing, psychosocial researchers and clinicians, pays attention to what people are saying — or not saying — as well as the underlying mood of the conversation, so as to tune into people’s underlying feelings, conflicts, and dilemmas.

Most importantly, attention is paid to ensuring people feel safe from attack, judgement or pressure. People can sense a mile away if we have an agenda. We go out of our way to signal that we are curious to learn about their experience and perceptions. Instead of the usual “How much do you agree/ disagree with X statement” questions commonly used in policy messaging research, the team courageously agreed to offer open-ended prompts that are meant to evoke more stream of consciousness answers, such as:

“What comes to mind when you hear X statement?”

“What associations do you have with Y topic?”

“What do you already know about Z topic? What have your experiences been?”

“Can you say more?”

And then:

“This is what I hear you saying. Did I get that right?” They’d reflect back what they heard.

The researchers would then pause, listen and intentionally create space for people to reflect — even if that meant gritting their teeth through the awkward moments of silence that most of us so often rush to fill.

I guided them to pay attention to what I call The Three A’s. Anxieties, Ambivalence (i.e. competing priorities), and Aspirations.

I call this “cracking the code” on climate psychology.

Using this method, the team conducted more than two dozen one-on-one interviews with a variety of conservatives: young adults, women, men, Hispanics, and Caucasians around the United States. They interviewed people who fall into a category of what the Yale Center on Climate Communication terms “soft skeptics,” as well as “hard skeptics.”

I was reminded of the doctoral research I conducted in Wisconsin in the late 2000s, where I focussed on how people were relating to issues facing the Great Lakes. There, I had discovered that many people, including those who identified as conservatives and not engaged in environmental protection or climate, had unexpectedly profound feelings about issues ranging from toxic contamination to biodiversity loss, which came forward as I listened, with no judgment or preexisting agenda.

Similarly, the interviews the team conducted uncovered lots of strong emotions about these big issues.

People felt scared of the specter of climate threats, if in fact real (several noted that “if the science was conclusive,” they’d take action, quit their jobs, and so on). They were aggrieved about perceived hypocrisy among climate advocates (“Al Gore flies around the globe, telling people to do what he is not willing to do!”); and overwhelmed by a profound sense of powerlessness and resignation (“There’s not much I could do about it, anyway, even if the issues were real”).

There was a strong current of underlying despair about the possibility that much about our cherished ways of life would need to change. And in response to this despair, I observed a brittle, rigid and harsh rejection of climate science.

Striking, too, was that people (yes: conservative climate skeptics) also had lots of ideas about solutions. They felt strongly about empowering individuals to innovate, using the power of the free market system, rather than locating the responsibility in government. And they recognized that this innovation would be linked to job creation and economic growth.

Perhaps the most significant finding to me, was that personal empowerment was important to respondents — they wanted to be part of the solution. They were tired of feeling patronized and spoken down to. They resented the tone of climate messaging and felt it was not taking into account the welfare of those who are most vulnerable. Particularly when it comes to transitioning out of extractive practices and energy sectors.

They could not tolerate being patronized or treated as if they did not care about what’s at stake.

Taking all of this in, without judgment, we set about crafting different kinds of messaging that were attuned to these feelings. We practiced what is called “reflective listening” and acknowledging those Three A’s as an experiment. For many people, these messy, complex feelings simply were not being named or acknowledged. We wanted to know what would happen if we openly acknowledged these feelings in a political message about climate change. I had not seen that done before.

We used what I introduced to Bob and his team as a “lateral” approach versus a “frontal” approach, something I had learned in my psychosocial research training. Far less effective was to raise the problem directly (frontal) which tended to elicit knee-jerk rejection and tuning out. Instead, we emphasized the (lateral) shared values of caring for and loving nature, and what makes America so remarkable — and the potential costs of losing these gifts. We spoke openly to the Anxieties, Ambivalence and Aspirations.

After much trial and error, a script was tested across several groups of conservative Americans, using live dial testing — in which viewers, using dials, respond to what words resonate and don’t — to obtain moment-to-moment feedback. The script acknowledged their appreciation for nature and wide-open spaces, the great outdoors, and that humans have not always been the stewards of creation we could be. We spoke to their aspirations of taking action, without demanding more from the working class than we expect from the nation’s leaders.

To our amazement, the messaging actually worked. With astonishment, we watched the dial test line on the screen move up, in response to people turning the dial on what resonates — as we named and acknowledged these Three A’s (people especially loved calling out Al Gore).

The groups resonated with – and responded positively to – messaging that openly affirmed and acknowledged their anxieties, ambivalence, and conflicts, as well as their deepest held aspirations for a healthy and sustainable world. They wanted to be included and listened to when it came to these profound existential threats.

Bob shared these findings with the Republican Party, urging them to use this messaging in the upcoming election. He urged politicians to see that their constituents actually cared about the future of our world, quality of life for our future generations, and wanted to address these issues with ingenuity and innovation, without harming the most vulnerable.

Unfortunately, the leaders Bob shared these insights with, were not willing to make this leap of faith. The messaging failed to make it onto the convention floor, key policies were not passed, and today, we can all see polarization on this issue is even more entrenched, and existential fears are more potent than ever.

What does this mean for us, now, today?

At this particular moment, it seems the gulf is impossibly massive between those who care about our planet, our species, our web of life, protection of those most vulnerable, and ensuring our planet is healthy and thriving for future generations — and those hell-bent on accelerating the most devastating and damaging practices.

This can lead to a profound despair that words cannot touch or describe. I know. I feel it, and live with this every day.

However, based on my experiences working with people around the world, including large organizations, leaders and teams — often involving deep listening and applying the skills of motivational interviewing, reflective listening, psychosocial methods and actual conversations — I know that under the surface of resistance, denial and contraction, is a lot of insecurity and fear.

I know that insecurity and fear makes us self-preservation focused. And this is what I see playing out at scale.

I also know that when we create the right conditions, attune to these underlying currents, speak to them, give space for acknowledging and giving our deepest fears oxygen, we can actually gain some traction. This is the basic premise of a trauma-informed and emotionally intelligent approach.

There are no easy solutions here, but I want to encourage us to consider how we can weave these practices into every aspect of our change-making work.

It is time for us to shift from “righting versus guiding.”

Whether we are working at high-level strategy, on the ground in our community, actively influencing, organizing, showing up at our jobs, we can foster conditions that create safety and the ability to name our fears. This also has to do with how we convene. We need to partner and involve people who have psychological training into our climate work, our gatherings, our elite meetings and strategies. We need to invest in training, skill-building and resources when it comes to these capacities.

The question is: Will we leverage them?

Dr. Renée Lertzman is a leading climate psychologist, strategist, advisor, and trainer. For over 20 years, she has partnered across sectors and political affiliations, with communities, leaders and organizations around the world to drive impact. She is the founder of ProjectInsideOut.net, a nonprofit initiative to scale psychological tools for planetary action that offers programs and workshops. You can learn more about her work at reneelertzman.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment