Political Climate Boomerang and World Chaos

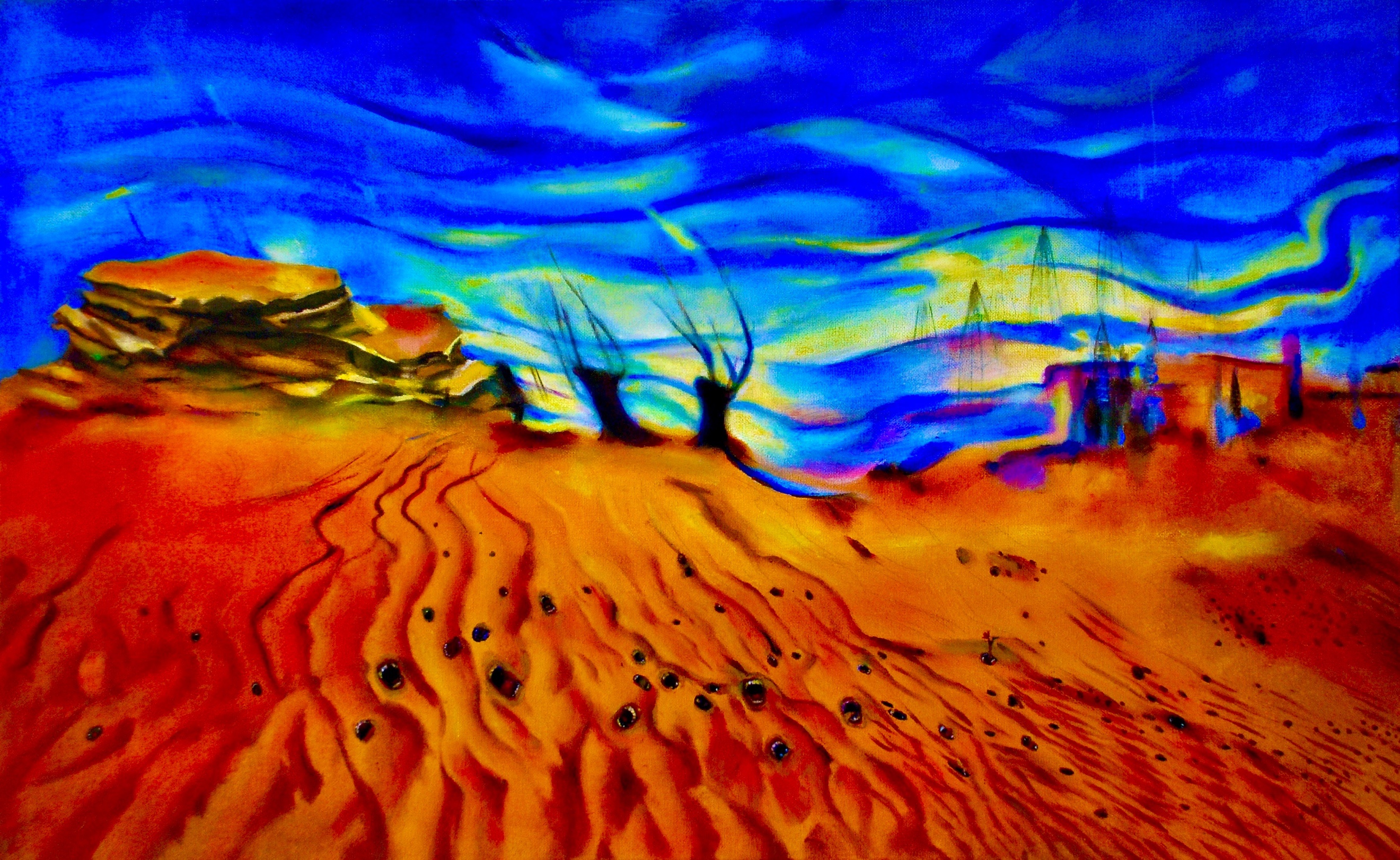

The Dead of the Middle East Petroleum by Evi Saranta. The oil machines extracting oil are seen in the distance. The black marks on the sand are the open mouths of the dead screaming without end, which the artist called νεκρών οιμωγές, ceaseless and extremely painful and tragic outbursts of crying.

President Trump is withdrawing the United States from the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which is the legal bedrock for pathbreaking efforts of the world to take a look at its footprint on planet Earth.

Is the US withdrawal from the environmental conventions of the UN undermining world safety and security?

First, the UNCCC, negotiated in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1992, started the conversation on what the human species is doing to its only nest in the universe. These activities include the petroleum-powered industrialization of agriculture, transportation, fighting wars and the primary heating of billions of homes by the burning of global warming natural gas. This massive use of petroleum, coal and natural gas did not bode well for the future of humanity and the myriad of species in the Amazon forest and other threatened forests the world over. So, the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change warned, though did not even try to regulate human activities, that humans were harming the planet and threatening civilization. Second, the 2015 Paris Agreement is a modest, though failing, global effort to control planetary temperature from getting too dangerous.

The executive secretary of the UNFCCC, Simon Stiell, said the withdrawal of the US will harm all, but especially the US. He said: “While all other nations are stepping forward together, this latest [US] step back from global leadership, climate cooperation and science can only harm the US economy, jobs and living standards, as wildfires, floods, mega-storms and droughts get rapidly worse. It is a colossal… goal which will leave the US less secure and less prosperous.”

The Trump administration, however, is under the delusion that its rejection of climatological science, persisting in the falsehood that climate change is a hoax, would miraculously revive prosperity in America, which, according to the US Fifth National Climate Assessment of November 14, 2023, is warming up 68 percent faster than any other country on the planet. The Assessment also warns that: carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere since the 1970s have been higher than at any time for the last 800,000 tears; sea level rise in the 20th century rose faster than at any time in the past 3,000 years; and drought in the Western US has been worse and persistent than at any time in the last 1,200 years.

Heat waves on land and seas, catastrophic fires, draught, hurricanes, rain bombs and storms embracing America are the results of a variety of human activities, especially the feeding and torturing of billions of food animals in thousands unregulated animal farms all over the country. These facilities become machines and factories of disease and toxic waste, stench and slaughter. They most likely gave the country and the world COVID-19, the 2020-2022 plague that killed millions of people and shut down the planet. I documented this potential origin of the pandemic in my latest book, Earth on Fire: Brewing Plagues and Climate Chaos in Our Backyards (World Scientific, 2026).

Animal factories are inhumane and dangerous. They emit large amounts of global warming gases like carbon dioxide and methane. The owners of these animal farms don’t treat the diseased and toxic wastes of the animals. They put the wastes in lagoons and spray them over farms. The very likely diseased meat of the slaughtered animals is not healthy for human consumption. Yet during the pandemic, the government ordered the slaughterhouses to remain open and continue their dangerous work.

Other activities and machines add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, like millions of airplanes flying; boats, yachts, ships, leaf-blowers, unfathomable petroleum-powered machines; the military, navy and air force training and fighting wars; cars and trucks, too many to count – most of them burning petroleum and polluting.

But the America First ideology of the Trump administration means “asserting control of the Western Hemisphere for the benefit of the United States.” This also connects the imperialism of the America First to the decision to withdraw from most UN organizations and programs, including “reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries.” Such an unpredictable and harmful step is not simply a return to the good old days – of selling Americans cheaper gasoline.

“The decision [of withdrawal from the UNFCCC] is not only an indicator of America’s rejection from global diplomacy, it’s a finger in the eye to the billions of people, including Americans, suffering through intensifying wildfires, storms and droughts, threats to the food supply and to biodiversity, and other dangerous and costly effects of a warming planet.”

“This is a shortsighted, embarrassing, and foolish decision,” said Gina McCarthy quoted by the New York Times. McCarthy is the former US EPA administrator and White House climate adviser during the Biden administration. She accused the Trump administration of discarding “decades of global collaboration.” She said:

“This administration is forfeiting our country’s ability to influence trillions of dollars in investments, policies, and decisions that would have advanced our economy and protected us from costly disasters wreaking havoc on our country.”

I agree with Gina McCarthy. Like her, I served at EPA, but certainly not in a political position. I worked as an analyst for 25 years, all the way from the Carter administration to the end of the first George W. Bush administration, 1979-2004. I witnessed lots of corruption, the industry, including the fossil fuel companies, pulling the political strings behind the regulations and policies of the ceaselessly less protective EPA. I also recognized aggression behind the industry efforts for deregulation.

In an October 10, 1989 article I wrote for the Chicago Tribune, I shed light on the pivotal role of petroleum companies behind climate change and the warming of the planet. When the Wall Street Journal reprinted a couple paragraphs from the article, the political reaction was swift. Senior EPA officials demanded that I be fired. They wrote me a “letter of reprimand,” step number one before firing. I took the letter to the EPA administrator Willian Reilly, who dismissed the baseless charges against me. And what an incredible coincidence and embarrassment for the EPA: sending me the threatening letter on Earth Day 1990. What was in the minds of those EPA bureaucrats? Certainly, not the Earth.

Some 36 years later, Trump is repeating and exceeding the aggressive deregulation of the irresponsible Reagan administration. Withdrawing from the vulnerable global efforts to control the man-made climate giant in the room is party a self-destructive impulse under the influence and corruption of the money of the fossil fuel industry and partly an imperial notion that might is right, even when history and science say no, might rarely if ever is equivalent to justice. Thinking America First most likely was behind the US pulled out of the UN convention of 1992.

“The decision to withdraw [from the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change] is part of an aggressive assault on climate efforts by President Trump. His administration has rolled back climate regulations, removed scientific data on climate change from government websites, thwarted the development of wind and solar energy and commissioned a federal report downplaying the effects of a warming planet.”

Yes, abandoning the United Nations is aggression – and much more. Trump treats domestic and foreign matters as if they did not differ. It’s not too difficult to see through the bluster of Trump, that: “the most chilling hallmark of Trump’s second presidency: the seamless fusion of domestic and foreign policy, bypassing America’s constitutional system of government to assume virtually boundless, unchecked power.”

Power corrupts

Indeed, power is at heart of this aggression and war against science, humanity, civilization and the planet.

After WWI, the victors headed by President Woodrow Wilson, crafted the League of Nations, 1919-1920. The purpose of this first global intergovernmental organization was to promote international cooperation, disarmament and peace. Yet the US never joined the League. Moreover, decisions demanded unanimity. The League also did not have the military to enforce its decisions. In the 1930s, Japan, Italy and Germany ignored international agreements and the League was impotent. The result was WWII.

After WWII, in 1946, the victors created the United Nations to replace the League. The UN has had more success than the League. However, just like the League, the presence and support by the US is a critical factor in its thriving or decline and extinction and the almost certain wars that follows its demise. So, Trump’s grabbing of Nicolas Maduro, president of Venezuela, and treating him like a criminal in the US, while, simultaneously, getting out of long-standing agreements with the United Nations may be symbolic blows to international order. The world is in potential anarchy and chaos, not much different than the anarchy and aggression of unchecked Germany that sparked WWII.

Epilogue

Fossil fuels, especially petroleum, is behind the existential climate emergency, the blindness of the ruling classes to put humanity, civilization and planet Earth first. The other charge is a US administration thoroughly captured by fossil fuels, risking health, security, democracy and the planet for short term profits.

American politicians, professors-intellectuals and environmentalists, no matter their party affiliation, should act together to repair the damage to the United Nations and the fragile international order of the rule of law. The Senate should exercise its authority and rejoin the US to the UN conventions and programs. Maduro may be a bad leader, but his trial should take place in Venezuela, not in the US.

Doing nothing is unacceptable. It may trigger more wars, more deregulation, more pollution, more global ecocide, higher planetary temperature — and anarchy and chaos in societies and the already stressed Mother Earth, our sole home in the Cosmos.

The European climate movement is faltering. State repression has escalated. Authoritarianism is on the rise. And even though most people around the world support climate action, they consistently underestimate how much others care — giving people the sense their concern is not shared. Groups like Just Stop Oil and Climate Defiance deserve credit for keeping climate in the headlines. But any movement whose only visible face is civil disobedience will struggle to expand beyond its core.

So what could create renewed momentum?

Every day, extreme weather events are creating a new wave of climate activists, many of whom have never attended a protest or signed a petition. These are people whose homes have flooded or whose communities have been destroyed by storms or wildfires. For them, climate change isn’t abstract. Their houses are literally on fire. These communities are facing immediate crisis, and they’re in the headlines with increasing regularity. From these tragedies, there’s a window of possibility for political change.

Between 2000 and 2019, floods alone affected over 1.65 billion people globally, killing more than 100,000. Rising temperatures made last year’s Valencia floods twice as likely and 12 percent more intense. Super Typhoon Odette in the Philippines caused $800 million in damages. Vermont’s 2023 flooding resulted in $1 billion in damage claims.

For climate organizers, these events do something that years of advocacy often can’t: They make the connection between fossil fuels and real harms immediate and visceral. Recent research published in Nature found that while exposure to extreme weather alone doesn’t automatically increase support for climate policy, “subjective attribution” does. When people understand that a specific disaster was worsened by climate change and can connect it to specific corporate actors, their opinions shift.

Climate attribution science has become sophisticated enough to quantify how much a company’s emissions contributed to making a specific storm deadlier. Shell, for instance, is historically responsible for 41 billion tons of CO2 — more than 2 percent of global fossil fuel emissions. This isn’t abstract anymore. It’s evidence that can be used in courtrooms, legislative hearings and public campaigns.

This also creates a powerful economic pressure point. Climate disasters already cost insurers roughly $600 billion in losses from 2002 to 2022, yet many continue underwriting new fossil fuel projects. When disasters strike, this contradiction becomes politically untenable.

We’ve looked at three places where communities organized around extreme weather and won concrete victories — not just raising awareness or getting media traction, but tangible policy change and corporate accountability.

Vermont: Bipartisan coalition after consecutive floods

When Vermont experienced catastrophic flooding in July 2023, causing over $1 billion in damage, it came 12 years after Tropical Storm Irene, which had also caused devastation. Two such major floods galvanized an unusual coalition, which deliberately crossed party lines. The coalition’s strategy was pragmatic and studiedly nonpartisan. Environmental groups like Vermont Natural Resources Council and the Sierra Club joined forces with farmers whose fields had been destroyed and small business owners whose livelihoods were underwater. State Sen. Dick Sears framed the Climate Superfund Act around a principle everyone could understand: “The polluter pays” — those responsible for damage should pay for it.

Being bipartisan in these times is noteworthy in itself. Extreme weather events might be that rare thing that can overcome the paralyzing power of polarization and change the political arithmetic. The bill passed the Vermont Senate 21-5 and became law in May 2024 — the first of its kind in the U.S. It requires fossil fuel companies that have produced more than 1 billion metric tons of CO2 to pay their share of Vermont’s climate damages.

What made this work? Organizers centered affected communities, used climate attribution science to make connections concrete, framed the campaign around a morally-uniting principle — “polluters pay” — rather than partisan climate politics, and moved quickly while memories of flooded homes were still fresh in everyone’s minds.

Philippines: Innovative legal strategies and international solidarity

When Super Typhoon Haiyan hit in 2013, killing over 6,000 people, survivors didn’t just mourn, they organized. The disaster exposed deep failures: aid arrived slowly, reconstruction stalled amid corruption, and billions in promised assistance never materialized. Protests erupted demanding accountability.

In 2015, Haiyan survivors partnered with Greenpeace Philippines to petition the Commission on Human Rights to investigate 47 fossil fuel companies for human rights violations related to climate change. This launched the world’s first investigation into corporate responsibility for climate impacts. In 2022, the commission found that fossil fuel companies could be held morally and legally responsible.

A few years later, following severe flooding in Manila, Greenpeace highlighted government failures and pointed to up to $19 billion lost to corruption since 2023. Public anger intensified, culminating in powerful protests that forced corruption and climate accountability to the top of the agenda. This surge of public pressure gave the CLIMA Bill — establishing frameworks for climate loss and damage, corporate accountability and reparations — the momentum it needed.

The decade of activism and organizing is now entering a new phase. In October 2025, 67 survivors of Super Typhoon Odette filed the first civil lawsuit directly linking a fossil fuel company to deaths in the Global South. The survivors are suing Shell in U.K. courts using attribution science showing climate change more than doubled the likelihood of the extreme event.

Survivors and NGOs need public momentum to give them the political power for legal strategies to have teeth. Crucially, over decades organizers had built the infrastructure to act when the next disaster hit.

Spain: From floods to a National Climate Emergency Pact

The Valencia floods of October 2024 killed 237 people and displaced thousands. Images of cars floating down European streets better known for their cafes shocked people worldwide. The local reaction was mass mobilization: More than 130,000 marched in Valencia, demanding accountability from officials who had delayed emergency warnings.

Organizers didn’t stop at demanding resignations; they wanted systemic change. In August 2025, following the floods and devastating summer wildfires, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez announced a Climate Emergency Pact, which includes concrete measures such as a new State Agency for Civil Protection and Emergencies, year-round firefighting staff, and mandatory corporate carbon reporting. Billions in funding for climate adaptation infrastructure, probably the key element of any future resilience, are still “potential” and will require more grassroots pressure.

As with Vermont, organizers used the disaster to build a coalition transcending political divisions, bringing together administrations, civil society, science, business and trade unions.

What organizers can learn

1. Act fast. When extreme weather strikes, both the media and climate skeptics move swiftly to influence the narrative. It’s crucial to be prepared. Offer direct assistance and help local community campaigns broadcast their demands.

2. Center affected communities. The most powerful voices in these stories were those of farmers who lost crops, business owners whose storefronts flooded, parents who lost children — not climate activists. These voices cut across political lines. Climate activists must step back to let authentic local voices lead.

3. Use attribution science strategically. Climate attribution research has become sophisticated enough to quantify corporate responsibility and it’s getting better and faster every year. Vermont used it to calculate damages. The Philippines case relies on it to prove Shell’s contribution. This transforms abstract climate change into concrete accountability.

4. Use real stories as well as facts. Stories of real people, particularly first responders, cut through most effectively. When firefighters say extreme weather events are growing more frequent, people believe them.

5. Build unusual coalitions. Vermont united environmentalists with Republican farmers. Spain brought together unions and businesses. The Philippines connected survivors across multiple disasters. Diverse partnerships are stronger.

6. Make concrete demands. These campaigns identified specific villains — fossil fuel companies — and specific responses: climate superfund laws, corporate liability, emergency infrastructure. People rally around clear targets.

The path forward

Extreme weather events will keep happening, affecting more people and causing more damage and heartbreak. They’re moments of crisis and clarity when the world’s ears are more open. But they’re not without risk — in Valencia, the far-right Vox party was first on the scene, attempting to deflect the narrative away from climate. The climate movement must step in to seize the narrative.

Cathy Rogers

Dr. Cathy Rogers PhD is Director of Research and Development at Social Change Lab, a nonprofit that conducts research on protest and people-powered movements to understand their role in social change.

Maciej Muskat

Maciej Muskat has worked for Greenpeace for the last 22 years, leading and advising on different campaigns across many countries, most recently as Extreme Weather Events Lead at Greenpeace International.