EU leaders consider some of the 28 points of the American plan for resolving the Ukrainian conflict unacceptable and the number of items on the list has been parred back to 19, the Financial Times reported on November 24.

Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk stated this following an informal EU summit on Ukraine in Luanda on the sidelines of the EU-African Union summit on November 24.

"There's little reason for hurrah-like optimism. <...> There's absolute agreement among European leaders that work on the 28 points presented several dozen hours ago must continue, some of which are unacceptable," the prime minister said at a briefing broadcast on his office's social media pages.

The Kremlin rejects many of the amendments made by the Europe that was floated last week and discussed by Ukraine and its western allies in Geneva on November 23, according to Yuri Ushakov, Putin’s top foreign policy advisor.

Ushakov said the original version he had seen contained many points that were agreed at the Alaska summit between US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin on August 15, which were largely acceptable to the Kremlin. However, many of the new elements introduced by Europe at the weekend were not acceptable. \

Once Ukraine and its western partners have thrashed out a compromise version that is acceptable to them, the proposal will be shared with the Kremlin for more talks to try and find a workable final version that will be the basis for a ceasefire in the almost four year long war.

European leaders were not satisfied with the clause on reducing the Ukrainian Armed Forces' numbers. Furthermore, Tusk himself emphasized the need to maintain sanctions pressure on Russia.

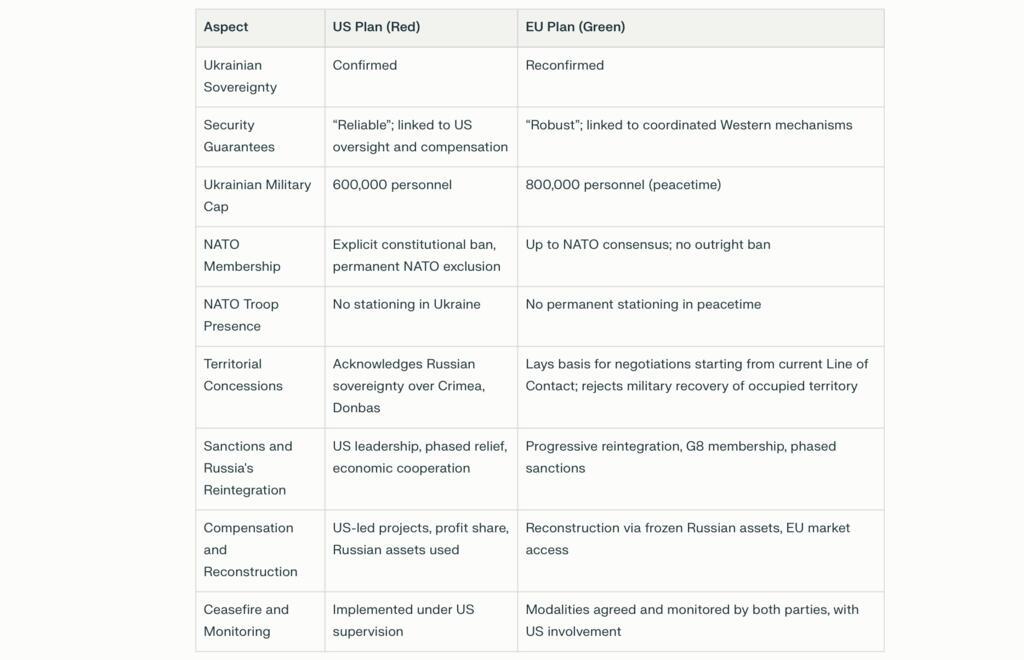

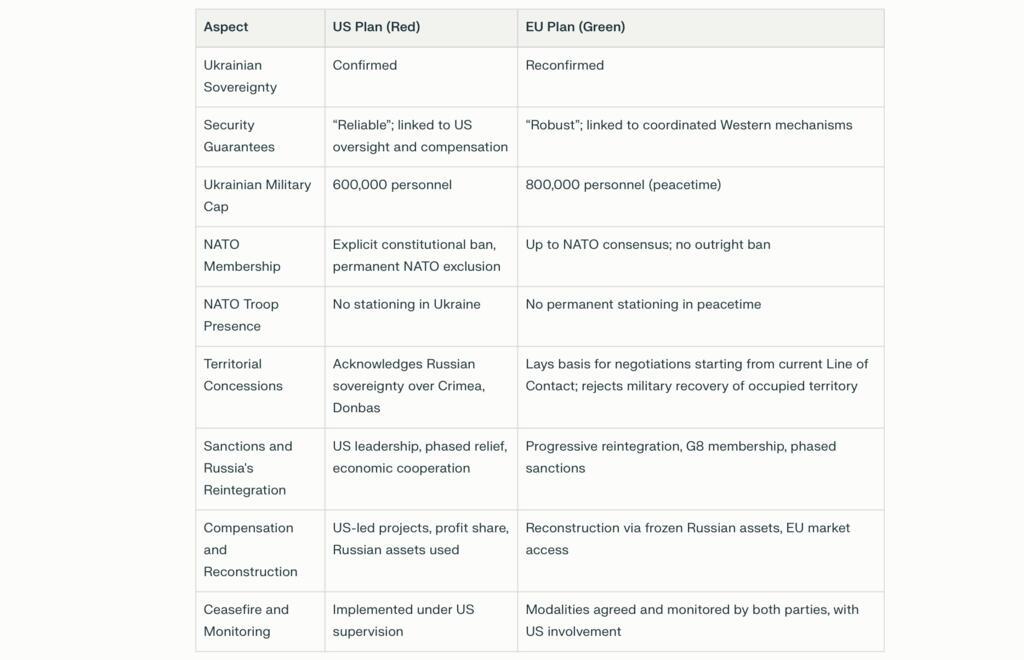

The plan previously suggested a cap of 600,000 men be placed on the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), but the EU wanted that limit increased to 800,000, which would give Ukraine by far the largest army in Europe.

The US proposal also called for sanctions relief and reintegrating Russia’s economy into the global economy, but sanctions would be removed on a case by case basis and no timeline was given.

Tusk noted that a clause on deploying Nato fighter jets to Poland as a security guarantee for Kyiv had been removed from the proposed plan. US Secretary of State Marco Rubio said at a press conference at the end of the day of talks in Geneva that there were now two versions of the plan, one with 28 points and another with only 26.

The clause to allocate $100bn from Russia’s frozen assets to a reconstruction fund has also been excluded, according to Bloomberg citing sources. The proposal stipulated that the US would receive 50% of the profits from the unspent assets, which would be transferred to a US-Russia investment fund.

The question of territories has also been fudged and the substantive decisions on territories will be put off to be discussed at a face-to-face meeting between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy, according to Ihor Brusilo, deputy head of the Ukrainian presidential administration, speaking to Bloomberg.

If this idea is accepted then it would be a repeat of the format proposed as part of the Istanbul peace deal in April 2022, when it was decided that questions regarding the sovereignty over the Crimea were to be put off for direct negotiations between the two presidents at that time as well.

During a press conference after the talks in Geneva were wrapping up, Rubio said the number of items on the list had fallen to 26, but the Financial Times subsequently reported that the list has been reduced further and now only contains 19 times, citing people briefed on the discussions. The people did not specify which elements had been removed.

RBC-Ukraine, citing sources, reported that most of the provisions of the American peace plan were agreed upon and partially amended during the Geneva talks. According to the publication, the delegations were able to reach agreements on several points including:

- Agree on the size of the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) cap set at 800,000, up from the original 600,000 men;

- the control over the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP) should be returned fully to Ukraine’s control;

- the format for prisoner exchanges, and the return of convicted prisoners.

These points were finalized following discussions that the negotiators described as "the most productive in the past ten months." Washington also assured European partners that their concerns regarding EU and Nato security guarantees will be taken into account during the subsequent talks.

The parties decided to postpone discussions on territorial concessions and the constitutional provision stipulating Ukraine's non-accession to Nato and push them to the presidential level at a proposed meeting between Putin and Zelenskiy.

Separately, Politico reported that an alternative 28-point plan for Ukraine prepared by so-called E3 (Germany, France, and the UK) has lost its relevance, after other EU officials present at the Geneva talks refused to support the project.

One EU official told Politico that the E3 proposal document was "already outdated," while other diplomats said it did not reflect the current state of the consultations, which were clearly moving very fast.

Hungary has remained firm in its opposition to further European support for the war and thrown itself behind the US peace plan to bring the fighting to an end.

The EU once again is undermining the peace agreement between Russia and Ukraine being negotiated by the US, Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto said on Facebook. In his opinion, all European politicians are “obliged to unconditionally support the peace plan,” since this is in line with the principles of “humanity and common sense.”

Europe demands more work on US peace plan to end Russia-Ukraine war

The United States has set a Thursday deadline for Ukraine to accept its controversial 28-point peace plan, placing Kyiv’s embattled government under acute pressure. US President Donald Trump has described the proposal as “a starting point”, but both the substance and the process have provoked concern in Ukraine, Russia, and many European capitals.

Issued on: 24/11/2025

RFI

Head of the Office of the President of Ukraine Andriy Yermak, left, and US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, right, talk to the press as their consultations continue at the U.S. Mission to International Organizations in Geneva, Switzerland, Sunday, 23 November, 2025. © Martial Trezzini / AP

The US peace plan requires Ukraine to cede Crimea and much of the Donbas to Russian sovereignty, cap its military at 600,000 personnel, and constitutionally commit to never joining NATO.

The proposed settlement also offers phased sanctions relief and economic reintegration for Russia, in exchange for a non-aggression pact and “reliable” US-led security guarantees for Ukraine.

Notably, European leaders learned of the plan only belatedly, and it was drafted without Ukrainian input, raising alarm about its fairness and longevity.'

'Difficult choice'

Ukraine’s leader Volodymyr Zelensky faces what he calls “a very difficult choice”, weighing the prospect of losing vital US support against the indignity of territorial loss and strategic compromise.

“The Ukrainian government will not agree to these conditions,” according to Oleksandr Merezhko, chair of Ukraine’s parliamentary foreign policy committee. “For us, it means surrender,” he says.

Russian officials have publicly welcomed elements of the US draft that align with Kremlin positions but remain wary about enforcement, with the non-aggression pact echoing past agreements that Russia breached.

But EU foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas said that “it’s clear Russia wants to cement its gains and restore its position in the global economy, but this plan does not require genuine concessions,” adding that “for any plan to succeed, it must have the support of Ukrainians and Europeans”.

In this photo provided by the Press Service Of The President Of Ukraine on Nov. 21, 2025, Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelensky looks into the camera while delivering a video address to the nation in Kyiv, Ukraine. AP - Press Service Of The President Of Ukraine

European commentators and senior diplomats have also voiced strong concerns. German political scientist Constanze Stelzenmüller from the Brookings Institution described the US plan as “outrageous”, warning that “If implemented, it would allow Russia to become the apex predator in Europe. It represents a complete degradation of diplomacy.”

The abrupt nature of the US process, and its perceived disregard for European consultation, may weaken the West’s united front in future negotiations.

Experts suggest the plan is unlikely to gain acceptance “without further substantial revision and credible international guarantees”, according to a senior Chatham House analyst.

Chatham’s Orysia Lutsevych described Trump’s plan as effectively a "brainchild of the Kremlin," presenting Russian demands as an American peace plan and resembling a demand for Ukrainian capitulation.

She noted it limits Ukraine’s sovereignty, imposes territorial concessions, and dictates military and political terms unfavourable to Kyiv.

Her colleague Keir Giles characterised it as a transmission of Russian surrender demands facilitated by the US, “unrealistic and unenforceable,” with an inherent risk that Russia seeks to leave Ukraine defenceless for future aggression.

Both stress that meaningful negotiations require Ukrainian and European backing to modify or reject the plan point by point rather than wholesale acceptance.

Europe’s counter proposal

On Sunday, an EU counter-proposal, (as seen by Reuters) unveiled in response to US pressure, avoids explicit territorial concessions, proposing that the lines of contact be the starting point for future negotiations.

It allows Ukraine to keep a larger standing army (up to 800,000), and does not bar NATO membership outright – opting instead for “robust” coordinated security guarantees that could evolve with future alliances and consensus.

Reconstruction would be funded via frozen Russian assets and broad EU market access, aiming for a longer-term, balanced reintegration of Russia into global institutions.

Zelensky pushes EU to unlock €140bn in frozen Russian assets

At an EU-Africa summit in Angola, where emergency talks on the US proposal completely overshadowed proceedings on Monday, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz said that Russia must be involved in any talks.

"The next step must be: Russia must come to the table," Merz declared.

"If this is possible, then every effort will have been worthwhile," he added.

Comparison of differences between the US and European peace proposals regarding the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. © RFI/Jan van der Made

As the Thanksgiving deadline looms, the prospects for the US plan appear bleak.

Ukrainian leaders, with broad civil society support, remain unwilling to accept deep territorial losses or restrictions on sovereignty.

Russia, while pleased with many provisions, might object to certain security arrangements and demands for military withdrawal and remains sceptical.

"Russia has not so far received the official text of the American version of the Ukrainian settlement plan, which was adjusted during consultations between the United States and Ukraine in Geneva,” according to Russian spokesperson Dmitry Peskov quoted by Tass news agency on Monday.

EU chiefs hailed progress towards a deal but also said there were outstanding issues to resolve.

"There is a new momentum in peace negotiations," European Council President Antonio Costa said on the sidelines of the summit in Angola.

"While work remains to be done, there is now a solid basis for moving forward," added European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen.

For his part, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio said "tremendous" progress had been made at the talks.

"I honestly believe we'll get there," Rubio said, adding: "Obviously, the Russians get a vote."

(With newswires)

Rubio Praises Geneva Talks With Ukraine, Says Trump ‘Pleased’ With Progress

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio (r) and Ukrainian delegation head Andriy Yermak. Photo Credit: @AndriyYermak, X

November 24, 2025

By RFE RL

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio has said there has been “tremendous progress” at talks on ending the war in Ukraine, and that President Donald Trump was “pleased” when he briefed him on the discussions.

Rubio spoke to reporters for a second time on November 23, after talks with a Ukrainian delegation in Geneva that he earlier said had been “the most productive and meaningful” since the Trump administration took office in January.

“There’s still some work to be done, but we are much further ahead today at this time than we were when we began this morning and where we were a week ago, for certain,” Rubio said.

He did not elaborate on what the points were, but said security guarantees for Ukraine were something that “has to be discussed” and that work would continue on November 24.

The meetings in the Swiss lakeside city are focusing on a US plan to stop fighting that has raged since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

The plan has not yet been officially disclosed, although key elements have been leaked — sparking Kyiv’s allies to suggest that it is highly tilted in Russia’s favor.

Trump had earlier said the plan was not his final word, suggesting changes could be made to it. But in comments on Truth Social on November 23 indicated frustration with European and Ukrainian positions.

“Ukraine’s ‘leadership’ has expressed zero gratitude for our efforts, and Europe continues to buy oil from Russia,” he wrote in all-caps comments.

Two European Union member states still purchase Russian crude oil: Hungary and Slovakia. NATO-member Turkey also buys Russian crude.

Apparently responding in a social media post, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy pointedly stated his gratitude “personally to President Trump” for help that “is saving the lives of Ukrainians.”

In a later post, Zelenskyy also gave an impression of the pace of diplomacy in Geneva.

“A lot is changing – we are working very carefully on the steps needed to end the war,” he said. “Tomorrow will be no less active.”

What’s In The Deal?

Many of the terms of the proposed deal require sweeping concessions by Kyiv and appear to mirror many of the Kremlin’s demands — including surrender of Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk regions — known as the Donbas — and Crimea, along with setting limits on the size of its military.

Kyiv would also be required to enact a constitutional prohibition on joining NATO, while restrictions would be put on the Western military alliance itself regarding the stationing of its troops. Financial sanctions on Moscow would also be eased under the plan.

In return, Ukraine would receive some form of “security guarantees,” most notably from the United States, be allowed to join the European Union, and receive some financial benefits. Russia would also be required to withdraw from some Ukrainian areas it currently occupies.

Amid pushback from US lawmakers and foreign allies, Trump on November 22 left open the possibility of changes being made to the plan.

Asked by reporters if his proposal was his “final offer to Ukraine,” Trump said, “No.”

Ukraine’s European allies, who were not involved in drafting the US plan, have said the proposal requires “additional work.”

Reuters news agency reported details of European counterproposals that included a larger force size for Ukraine and a US security guarantee like NATO’s Article 5 — under which an attack on one country is considered an attack on all.

Rubio said he had not seen any European counterproposals.

Democrats, Republicans Push Back

The US plan has also received criticism among influential members of Trump’s own Republican party, including a joint statement with rival Democrats that calls for changes in the proposal.

“We will not achieve that lasting peace by offering [Russian President Vladimir] Putin concession after concession and fatally degrading Ukraine’s ability to defend itself,” said the statement, signed by three Democrats, one Republican, and one independent senator.

Veteran Republican Senator Mitch McConnell, a former Senate leader, wrote on X that “rewarding Russian butchery would be disastrous to America’s interests.”

Republican Roger Wicker, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, said he is “highly skeptical” the plan will bring about peace.

Rubio has denied remarks by Republican Senator Mike Rounds, Democrat Jeanne Shaheen, and independent Angus King that the proposal was not drafted by Washington but was the Kremlin’s “wish list” handed over by the Russians.

Western media outlets have cited sources as saying the document was largely the product of talks between Witkoff and a special envoy for Putin, Kirill Dmitriev.

Meanwhile, officials in Russia and Ukraine reported on new strikes on November 23.

An 11-year-old girl was among 19 people injured by drone strikes in Ukraine’s Dnipropetrovsk region, said Vladislav Haivanenko, head of the regional military administration.

Moscow’s Vnukovo airport suspended flights as the city’s mayor, Sergei Sobyanin, reported incoming Ukrainian drones.

Zelenskyy has said his country faces “one of the most difficult moments” in its history, warning that it risks losing one of its key allies — Washington — but that Kyiv would not “betray” its own interests in any negotiations.

RFE/RL journalists report the news in 21 countries where a free press is banned by the government or not fully established.

The US ‘Bait And Switch’ Operation Targeting Putin’s ‘Root Cause’ Principles – OpEd

November 24, 2025

By Alastair Crooke

So, now we have the details of the 28-point so-called ‘peace plan’ which Ukrainian Parliamentarian Goncharenko has provided claiming it to be a translation from the original.

The text – written as a putative legal treaty – will strike any experienced reader as an amateur production, hinging, in several parts, on ‘subsequent discussions’ and on ‘expectations’.

That is to say, much is left ambiguous, vague nor firmly nailed down. Such a plan would, of course, be – in the round – unacceptable to Moscow (although they may not disavow it outright). Even so, the plan has aroused fury and pushback in Europe. The Economist (reflecting the Establishment view) calls the paper “a terrible American-Russian proposal … which checks off many of [Russia’s] maximalist demands and adds a few more”.

The Europeans and Britain want Russian capitulation, pure and simple.

The point here, which Moscow makes clear, is that Kirill Dmitriev – Steve Witkoff’s interlocutor in the drafting – does not represent President Putin, nor Russia. He has no official mandate whatsoever.

Putin spokesman Dmitri Peskov curtly states:

“There are no formal consultations between Russia and the U.S. on the settlement in Ukraine; but contacts exist. Maria Zakharova stated that “the Russian Foreign Ministry has received zero official information from the U.S. about any alleged ‘agreements’ on Ukraine that the media is enthusiastically circulating””.

“Moscow’s position is that Russia is open to dialogue only within the ‘boundaries of its stated principles’, and the U.S. has not, as of yet, offered anything official that could serve as a starting point”.

So what is going on? Two politically inexperienced ‘non-envoys’ have had conversations, and out of these talks have stitched together some apparently speculative proposals. It is not even clear whether Dmitriev had a nod of assent for his talks with Witkoff in the U.S. in October, or whether he was acting on his own initiative. Russia’s Foreign Ministry is disavowing any knowledge of the content of these extensive discussions. It would be extraordinary if Dmitriev was keeping nobody in Moscow in the loop.

In any event, President Putin has sent his own riposte to the flood of stories circulating in the western media (based on leaks to Axios apparently deriving from Dmitriev):

Dressed in military uniform, Putin visited the command post of Battlegroup West on the front line, where he simply stated that the Russian people “expect and need” results from the Special Military Operation (SMO): “The unconditional attainment of the goals of the SMO is the main objective for Russia”, he said.

Putin’s response to the U.S. therefore is clear.

It looks then as though this discussion document written from the American perspective was conceived as a classic ‘bait and switch’ exercise. Secretary Rubio has repeatedly saidthat he doesn’t know “whether Russia is serious about peace – or not”:

“We’re testing to see if the Russians are interested in peace. Their actions – not their words, their actions – will determine whether they’re serious or not, and we intend to find that out sooner rather than later … There are some promising signs; there are some troubling signs”.

So, the proposals likely have been a ‘set up’ to test Russia. For example, they ‘test’ Russia in multiple areas:

“It is expected … that NATO will not expand further, based on dialogue between Russia and NATO, but mediated by the U.S.; Ukraine will receive ‘reliable security guarantees’ [undefined]; the size of Ukraine’s armed forces will be ‘limited’ [sic] to only 600,000 men; the U.S. will be compensated for these guarantees; should Russia invade Ukraine, [then] in addition to a decisive coordinated military response, all global sanctions will be reinstated, recognition of new territories and all other benefits will be revoked; the U.S. will cooperate with Ukraine on joint reconstruction … and operation of Ukraine’s gas infrastructure, including pipelines and storage facilities”.

“The lifting of sanctions [on Russia] will be discussed and agreed upon gradually and on an individual basis”.

“$100 billions of frozen Russian assets will be invested in U.S.-led reconstruction and investment efforts in Ukraine. The United States will receive 50% of the profits from this undertaking; Russia will legislatively enshrine a policy of non-aggression toward Europe [no mention however, of any reciprocity by Europe].

“Crimea, Luhansk, and Donetsk will be recognised de facto as Russian; Kherson and Zaporizhzhia will be frozen along the line of contact, which will mean de facto recognition along the line of contact; Russia renounces other annexed territories”.

This paragraph effectively amounts to a ceasefire – not a peace settlement – with recognition being only de facto (and not de jure):

“This agreement will be legally binding. Its implementation will be monitored and guaranteed by a Peace Council headed by President Trump”.

“Once agreed, the ceasefire will enter into force”.

This set of proposals is not likely to be accepted by the Europeans, Russia or even Zelensky. Their purpose is to dictate a completely new start-point to any negotiation. Any Russian concessions stipulated in the text will be ‘pocketed’ by the U.S., whilst the rug will be pulled on Russia’s ‘stated principles’. The pressures on Russia will escalate.

In fact, escalation has already begun. Coinciding with publication of the proposals, four long-range U.S.-supplied and targeted ATACMS were fired deep into Russian pre-2014 territory at Voronezh, which is where Russia’s over-the-horizon strategic radars are situated. All were shot down, and Russian Iksander missiles immediately destroyed the launch platforms and killed the 10 launch operators.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has threatened yet more sanctions for Russia, and Trump has indicated that he is ok with Senator Lindsay Graham’s 500% sanctions proposal for those trading with Russia – provided that he, Trump, has complete discretion over the new sanctions package.

The overall aim to these proposals clearly is to corner Putin, and push him off his fundamental principles – such as his insistence on eliminating the root causes to the conflict, and not just the symptoms. There is no hint in this paper of any recognition of root causes [expansion of NATO and missile emplacements] beyond the vague promise of a “dialogue [that] will be conducted between Russia and NATO, mediated by the United States, to resolve all security issues and create conditions for de-escalation, thereby ensuring global security and increasing opportunities for cooperation and future economic development”.

Blah, blah, blah.

It seems that escalation is ahead. Russia will need to consider how to militarily deter the U.S. effectively, yet without starting up the steps of the escalatory ladder to WW3.

The balance between deterrence and keeping a door open to diplomacy is a fine line – Too great an emphasis on deterrence may (counter-productively) only incite a countervailing ratchet up the escalatory ladder by an adversary.

Whereas too much emphasis on diplomacy, may well be perceived by an adversary as weakness and invite an escalation of military pressures.

The Witkoff-Dmitriev proposals may (or may not) have been well intentioned, but the keepers of the deep architecture of global redemptio equitis are unlikely to allow Russia to preserve its ‘contrarian’ values.

Kirill Dmitriev, it appears, may have been ‘suckered’.

Alastair Crooke

Alastair Crooke is a former British diplomat, founder and director of the Beirut-based Conflicts Forum.

What Europe Should Do About A Bad Ukraine Deal – Analysis

Soldier with the Ukraine flag. Photo Credit: NATO

November 24, 2025

ECFR

By Jana Kobzova

On the positive side, the Ukraine-Russia peace plan advanced by the US government earlier this week shows that Donald Trump remains committed to securing a deal.

On the negative side, however, the list is rather longer. Apparently cooked up by American and Russian envoys Steve Witkoff and Kirill Dmitriev—though the exact authorship remains murky—the deal would blow through a series of red lines long held in Europe and, until recently, the US too. Borders cannot be changed by force? All countries are equally sovereign and free to choose their foreign partners and alliances? No third party should hold a veto over who becomes a NATO member? All gone in the 28 points shared by US officials, which seem to stem from a different assertion: the strong do what they want and the weak suffer what they must.

28 steps… to the next war

But more than principle is at risk in this deal. In practice it would create a material threat to Ukraine’s independent existence: from capping the numbers of its armed forces personnel to forcing Kyiv to both abandon the territories it still controls in Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts and recognise Russia’s control over them. Ukraine’s withdrawal from the Donbas and that region’s demilitarisation would create the ideal circumstances for Moscow to attack Ukraine again in a few years. It would strip Kyiv of its defensive “fortress belt” in the Donbas. And it would send a powerful signal of impunity by instituting an amnesty denying justice to Ukrainian victims of Russian war crimes. In short, it would erect a giant, eastwards-facing “come back soon” sign over the entire country.

Some in Europe question how much this would matter to the rest of the continent’s security. In fact, quite a lot: the proposal would tie its censure of Ukrainian NATO membership (which the deal would write into the country’s constitution) to a total stop on future NATO expansion of any sort. That would affect not just current candidate states like Bosnia and Herzegovina but also ones where there is an ongoing debate on their neutrality and potential NATO application, like Austria or Moldova.

Other shifts codified in the proposed deal are more subtly worded. To agree that “European fighter jets will be stationed in Poland” suggests that American ones—deployed under this or future US administrations—cannot be there. To propose a new pact between Russia, Ukraine and Europe that settles “all ambiguities of the past 30 years” evokes Moscow’s demands to move NATO infrastructure as far away from its own western borders as possible, effectively eliminating the alliance’s deterrence on its eastern flank. All this would create dangerous precedents affecting the whole of Europe. The success or failure of Europeans to revise it will shape not only Ukraine’s future but also that of the rest of the continent.

The reported architects of the deal, Witkoff and Dmitriev, are both real estate investors and strangers to international law and norms. Both serve strongmen leaders sensitive to losing face. In those origins lie weaknesses that Europeans can exploit:Vladimir Putin has not yet fully accepted the text (calling it a “basis” of a deal). That may be because the Kremlin is sceptical of the Trump administration’s ability to stick by its promises, or because it fears Dmitriev as a businessman has focused more on commercial matters than the security ones that matter most to Putin.

There also seem to be doubts on the American side. Some Republicans have already criticised the outline deal. Unpredictable as ever, Trump has himself described it as not the “final offer”.

Trump and Germany’s chancellor Friedrich Merz have reportedly agreed a working group to review the deal’s text and E3 advisors met with the Ukrainians and the US over the weekend of November 23rd—further showing that Europeans have time remaining to shape the final terms. There is an opening for them to achieve that, if they are focused and united enough to do so.

Ceci n’est pas un deal

There is, then, an opening: a chance for Ukrainians and Europeans to say to Trump “yes, but”. They have learned from experience that it is better to say this, and then try to change the US president’s mind behind the scenes.

But the duration of that opening may well be short. For all the objections to the 28 points among American officialdom, the Trump administration has made it clear that it is impatient for a deal and that Kyiv should not expect a better one if it seeks to wait it out. Behind this lies an implicit but serious threat: the US could halt its intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance support for Ukraine, with immediate and grave implications for Kyiv’s ability to defend itself or hit targets inside Russia.

In the next few days and weeks, Europeans will try to make the final deal better than the one currently on offer. As they do so, they should adopt these three priorities:

1. Challenge America’s judgement on the war’s trajectory

From US statements about the proposed deal, it is clear that Washington believes Russia’s position will not worsen in the next months, while Ukraine’s will deteriorate. This analysis risks tipping into fatalism, and Europeans can help push back against that by weakening Russia economically, militarily and on the actual battlefield.

Economically, Europe can continue to seek out and sanction Russia’s “shadow fleet”, its transport ships with concealed identities, much more thoroughly than it is doing now. That would cut the country’s oil revenues and thus its military budgets. The EU should intensify inspections of suspected ships in member-state territorial waters and should bring forward its plans to ban more shadow-fleet vessels.

Militarily, Europe can do more to disrupt Russia’s war infrastructure. Ukraine’s needs are broad, but one thing would make a particular difference. In recent months Kyiv has increased its attacks inside Russia, including on oil-refining facilities, undermining the Kremlin’s effort to shield its population from the impact of the war and thus limit the domestic backlash. Currently, Ukrainian strikes happen on a roughly biweekly basis, which is a long-enough time interval to let Russian authorities conduct quick fixes and repairs. Europe could enable Ukraine to reduce those intervals greatly by providing additional long-range artillery capabilities and support for Ukraine’s own production capacity.

On the battlefield itself, Europe can ensure Ukraine’s crucial ability to keep defending itself while negotiations with Russia are ongoing. Much of the talk in the past few months has focused on Ukraine’s amazing drone advances. But as the winter approaches and the weather worsens, drone use is decreasing and the need for battlefield artillery, including 155mm-caliber weapons, becomes more acute. Front-loading more such supplies now would help Kyiv hold the line and deny Moscow further advances, challenging Trump’s perception of the war’s trajectory. Europe can also help Ukraine become more self-sufficient in drone components. It still buys some of these from China, but some of the Ukrainian drone companies privately confirm[1] that they already produce as much as 80% themselves—and could do more with the right support.

European leaders talking to Trump should not just present the above measures to the US president as possible acts, but as commitments that will happen irrespective of his actions. Only thus do they have a chance of changing the administration’s perception of Ukraine’s prospects.

2. Use all available bargaining chips—and do not give them up without the right assurances

An US-Russia deal will leave many Europeans feeling powerless. But they should resist that reaction. The continent has significant leverage, and must now use it to maximum effect.

Naturally this includes European financial support for Ukraine, which now greatly exceeds the American contribution. But the core of this leverage is Russia’s frozen assets. The US-Russia deal proposes to transfer $100bn of these to a Ukrainian reconstruction vehicle controlled by the two external powers. But of the frozen Russian assets, the US holds no more than $5bn in value where Europe holds almost $200bn. So Trump’s plan, even as it currently stands, would require European cooperation.

EU talks on using those frozen assets are currently stalled due to opposition from Belgium, where many of them sit, and whose government fears legal repercussions if the assets are seized. Germany’s Merz, on the other hand, is now using real political capital to argue for using them to support Ukraine.

Europe can meaningfully shape the proposed peace deal if it moves fast on this topic. That means Merz and others brokering agreement and overcoming Belgian concerns. They should tie this action to critical scrutiny of the commercial dimensions of the US-Russian proposal, insisting that European publics would accept the use of European-based Russian assets to stabilise Ukraine and/or backfill European spending on the country’s defence—but it would be hard to accept that these will just generate mega-profits for American investors.

Relatedly, Europeans also need to spell out more clearly their commitment to Ukrainian security guarantees in the event of peace.

3. Come to the table with clear red lines upholding European sovereignty

European cooperation with any Ukraine peace deal must be conditional on a series of red lines upholding the continent’s own sovereignty. Europeans’ starting point should be that they will not curb their support for Ukraine, or agree to concessions on Ukraine, in the event of a deal that weakens their overall right to protect Europe’s own security.

As such:Decisions about which fighter jets are stationed on European territory will be made in democratic European states themselves rather than in Washington or Moscow.

Likewise, changes to the constitutions of European countries will be made in those states and not imposed on them from the outside.

Europe will not accept the precedent of external powers setting caps on a European country’s armed forces. It will also refuse to recognise territorial changes achieved through force, not least as doing so would potentially spell destabilisation not just in Ukraine, but also in the Western Balkans.

Where Moscow officials and propagandists rant about the “Nazi” regime in Kyiv, Europeans will judge partner governments not by the barbs and prejudices of others, but by relevant UN and Council of Europe conventions.

The US-Russia proposal begs many other questions. But what it lacks most of all is an answer to this one: what is the US actually ready to offer, besides acting as a broker of a capitulation deal for Ukraine, to secure peace?

It may sound facetious, but it is not. For this is the fundamental question before Kyiv and its European backers as the Trump administration moves towards a sell-out to Moscow. The US has already curbed its support for Ukraine. Much as it has been irresponsibly slow in investing in Ukraine and in its own defence and resilience, Europe has helped to fill the gap.

So today, what is the US actually putting on the table? What will Trump do if Ukraine signs up to the plan? How will he ensure that the country will not face a new, bigger war a few years down the line? Those are the questions Europeans need to ask themselves as they respond to a bad plan from America that will define the future of their own continent. They have been too slow. Their power is less than it should be. But they do have agency in this situation, and must use it.

It is said that Dean Acheson, as American secretary of state, once proclaimed the following of the Vietnam War: “It is worse than immoral, it is a mistake”. The US-Russia deal as it now stands would be just that.

It would, of course, be immoral: telling the world that democratic sovereignty and self-defence can be overridden with few lasting consequences. But more than that, it would also be a mistake. It would embolden an endemically revisionist Russia, teaching Moscow all the wrong lessons. It would weaken Europe as a whole. It would trade a bad war now for a worse one within a few years. Europeans and Ukrainians can help prevent that next war—if they act together now.

The author thanks her ECFR colleagues Jim O’Brien and Nicu Popescu for their input on this commentary.

[1] Private discussion with Ukrainian drone producer, 2025About the author: Jana Kobzova is co-director of the European Security Programme and senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. Her research interests centre around developments in eastern Europe, with a focus on Ukraine and on improving the EU’s response to crises in its neighbourhood

Source: This article was published by ECFR

ECFR

The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) is an award-winning international think-tank that aims to conduct cutting-edge independent research on European foreign and security policy and to provide a safe meeting space for decision-makers, activists and influencers to share ideas. We build coalitions for change at the European level and promote informed debate about Europe’s role in the world.

A draft of the 28-point plan reviewed by AFP:

1. Ukraine's sovereignty will be confirmed.

2. A comprehensive non-aggression agreement will be concluded between Russia, Ukraine and Europe. All ambiguities of the last 30 years will be considered settled.

3. It is expected that Russia will not invade neighbouring countries and NATO will not expand further.

4. A dialogue will be held between Russia and NATO, mediated by the United States, to resolve all security issues and create conditions for de-escalation.

5. Ukraine will receive reliable security guarantees.

6. The size of the Ukrainian Armed Forces will be limited to 600,000 personnel.

7. Ukraine agrees to enshrine in its constitution that it will not join NATO, and NATO agrees to include in its statutes a provision that Ukraine will not be admitted in the future.

8. NATO agrees not to station troops in Ukraine.

9. European fighter jets will be stationed in Poland.

10. The US will receive compensation for the security guarantees it provides. If Ukraine invades Russia, it will lose the guarantee. If Russia invades Ukraine, in addition to a decisive coordinated military response, all global sanctions will be reinstated and recognition of its new territories and all other benefits of this deal will be revoked. If Ukraine launches a missile at Moscow or St. Petersburg without cause, the security guarantee will also be deemed invalid.

11. Ukraine is eligible for EU membership and will receive short-term preferential access to the European market while this issue is being considered.

12. A powerful global package of measures to rebuild Ukraine will be established, including the creation of a Ukraine Development Fund, the rebuilding of Ukraine's gas infrastructure, the rehabilitation of war-affected areas, the development of new infrastructure and a resumption of the extraction of minerals and natural resources, all with a special finance package developed by the World Bank.

13. Russia will be reintegrated into the global economy, with discussions on lifting sanctions, rejoining the G8 group and entering a long-term economic cooperation agreement with the United States.

14. Some $100 billion in frozen Russian assets will be invested in US-led efforts to rebuild and invest in Ukraine, with the US receiving 50 percent of the profits from the venture. Europe will add $100 billion to increase the amount of investment available for Ukraine's reconstruction. Frozen European funds will be unfrozen, and the remainder of the frozen Russian funds will be invested in a separate US-Russian investment vehicle.

15. A joint American-Russian working group on security issues will be established to promote and ensure compliance with all provisions of this agreement.

16. Russia will enshrine in law its policy of non-aggression towards Europe and Ukraine.

17. The United States and Russia will agree to extend the validity of treaties on the non-proliferation and control of nuclear weapons, including the START I Treaty.

18. Ukraine agrees to be a non-nuclear state in accordance with the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

19. The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant will be launched under the supervision of the UN's International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and the electricity produced will be distributed equally between Russia and Ukraine.

20. Both countries undertake to implement educational programmes in schools and society aimed at promoting understanding and tolerance.

21. Crimea, Luhansk and Donetsk will be recognised as de facto Russian, including by the United States. Kherson and Zaporizhzhia will be frozen along the line of contact, which will mean de-facto recognition along the line of contact. Russia will relinquish other agreed territories it controls outside the five regions. Ukrainian forces will withdraw from the part of Donetsk Oblast that they currently control, which will then be used to create a buffer zone.

22. After agreeing on future territorial arrangements, both the Russian Federation and Ukraine undertake not to change these arrangements by force. Any security guarantees will not apply in the event of a breach of this commitment.

23. Russia will not prevent Ukraine from using the Dnieper River for commercial activities, and agreements will be reached on the free transport of grain across the Black Sea.

24. A humanitarian committee will be established to resolve prisoner exchanges and the return of remains, hostages and civilian detainees, and a family reunification programme will be implemented.

25. Ukraine will hold elections in 100 days.

26. All parties involved in this conflict will receive full amnesty for their actions during the war and agree not to make any claims or consider any complaints in the future.

27. This agreement will be legally binding. Its implementation will be monitored and guaranteed by the Peace Council, headed by US President Donald Trump. Sanctions will be imposed for violations.

28. Once all parties agree to this memorandum, the ceasefire will take effect immediately after both sides retreat to the agreed points to begin implementation of the agreement.

(FRANCE 24 with AFP)

UKRAINE CAPITULATION PLAN

Benjamin Netanyahu with Donald Trump at the Ben Gurion airport in May 2017. (Photo: Amos Ben Gershom GPO)

Benjamin Netanyahu with Donald Trump at the Ben Gurion airport in May 2017. (Photo: Amos Ben Gershom GPO)