(RNS) — 'A system that relies on fear, force and death to manage human beings is not broken at the edges. It is broken and rotten at the core,' the Rev. Abhi Janamanchi said. 'Stop excusing violence. Start protecting life. Abolish ICE.'

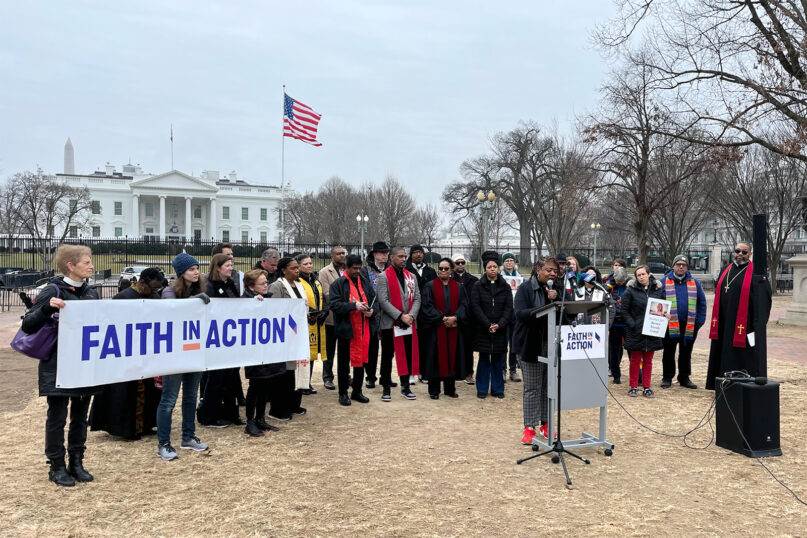

Bishop Dwayne Royster, right, asks attendees to call their elected officials during a vigil assembled by interfaith network Faith in Action, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026, in front of the White House in Washington. (RNS photo/Aleja Hertzler-McCain)

Aleja Hertzler-McCain

January 9, 2026

RNS

WASHINGTON (RNS) — A group of more than 50 faith leaders gathered outside the White House Friday (Jan. 9) morning to mourn the death of Renee Nicole Good, who was shot and killed by a federal agent Wednesday on a residential street in Minneapolis. The interfaith gathering also called for accountability for Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“This is what fear as policy looks like. It confirms what too many already know — that systems with enormous unchecked power can take life and then move on as if nothing has been broken,” the Rev. Abhi Janamanchi, senior minister at Cedar Lane Unitarian Universalist Congregation in Bethesda, Maryland, and an advisory board member of Hindus for Human Rights, said to the crowd, after describing the chest tightness and shortness of breath that he said many in immigrant neighborhoods are feeling.

The group, assembled by interfaith organizing network Faith in Action, echoed the demands of ISAIAH, their Minnesota affiliate: that Jonathan Ross, the ICE officer who shot Good, be charged and prosecuted, that federal authorities allow Minnesota investigators to take part in the investigation to ensure its integrity and that ICE cease its operations across the country.

“ A system that relies on fear, force and death to manage human beings is not broken at the edges. It is broken and rotten at the core,” Janamanchi said. “ Stop excusing violence. Start protecting life. Abolish ICE.”

The Rev. Starsky Wilson, the president and CEO of the Children’s Defense Fund, called the crowd’s attention to the stuffed animals in Good’s car that presumably belonged to her children.

“ Those implements of comfort were splattered with blood,” he said. “We come because this terror has reached our children,” he said, adding someone must “give account for the trauma to our children.”

A bullet hole is seen in the windshield as law enforcement officers work the scene of a shooting involving federal law enforcement agents, Wednesday, Jan. 7, 2026, in Minneapolis. (AP Photo/Tom Baker)

“ When we think of this past year in Minneapolis, we feel like it’s an attack on childhood,” Wilson said, mentioning the detentions of parents and the Trump administration’s threats to funding that supports children.

RELATED: Minneapolis clergy exposed to pepper spray after rushing to scene of deadly ICE shooting

The religious leaders, who were largely Protestant Christians, also connected Good’s death to the violence of other ICE operations and actions taken by the Trump administration, including strikes in Nigeria and the military operation in Venezuela that captured Nicolás Maduro, where the Venezuelan government has said more than 100 people were killed. At least nine people have been shot by ICE since September.

“God is not neutral about violence. God is not neutral about state power,” said the Rev. Cassandra Gould, political director for Faith in Action. “God is also not a God of silence, and neither is the church.”

Bishop Dwayne Royster, the executive director of Faith in Action, has been coming to the White House every Wednesday over the past few months. He told the crowd he kept returning to the White House because “somebody’s gotta hold Donald Trump accountable for all the evil that’s happening in this country.

“I pray that no peace comes into that place until they do right by the people of God,” he said. “ I pray that they can’t sleep at night until they do right by the people of God.”

Faith leaders join a vigil organized by Faith in Action, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026, in front of the White House in Washington. (RNS photo/Aleja Hertzler-McCain)

Faith in Action advocates in 24 states through 40 affiliate organizations, as well as 13 countries throughout the world, Royster said.

They began to sound the alarm about the Trump administration’s planned mass deportation campaign a week before his 2025 inauguration in a Newark, New Jersey, day of prayer and dialogue hosted by Catholic Cardinal Joseph Tobin, and they have continued to carry out immigration advocacy throughout his first year.

Through Good’s death, the Rev. Holly Jackson, associate conference minister for the Central Atlanta Conference of the United Church of Christ, told attendees that the state wanted to discourage such efforts.

“ They want us to be scared and to give up. They want us to turn in our neighbors. They want us to cower when they come knocking on our doors,” Jackson said. “ They want us to worship a God of white supremacy and stop preaching about the dignity and worth of every human being. They want us to deny that this is a land built by immigrants where justice and equality are supposed to be for all.”

But she said, “ in Renee’s name and in the name of countless others whose lives and families have been destroyed, we cannot and we will not give up.”

Two attendees of the vigil, The Rev. Stephanie Vader, senior pastor of Capitol Hill United Methodist Church, and the Rev. Rachel Landers Vaagenes, pastor of Capitol Hill Presbyterian Church, told RNS they had attended to “make hope visible” and represent their faith values.

It’s just one way the two congregations have been responding to the moment, which includes providing food, clothing and toys to immigrants, as well as accompanying them to immigration appointments, the pastors told RNS.

The Rev. Julio Hernandez, who leads Faith in Action Washington-area affiliate Congregation Action Network, spoke about the budget increase for immigration enforcement that has led to an increase in immigration agents in U.S. streets.

In the U.S., he said, “ the less pigment one carries, the more human one is deemed to be,” and the country “ has poured billions of dollars into capturing, detaining and terrorizing those who do not fit this narrow definition of belonging.”

But he countered, “ This tapestry of prayer, practice and presence is stronger than any wall, deeper than any border and more truthful than any system built on fear.”

In one of many prayers at the vigil, the Rev. Audrey Price, the interim pastor of the United Church of Christ of Seneca Valley, prayed, “Strengthen your church for such a time as this. Strip us of the comfort that numbs compassion. Deliver us from neutrality that disguises itself as peace. Break the chains of fear that keep us quiet while injustice speaks boldly in the streets.”

'She could have been any of us': Faith leaders mourn Renee Good in Minneapolis

MINNEAPOLIS (RNS) — 'It's all just too much, but my faith requires me to show up,' said the Rev. Dana Neuhauser.

Clergy members sing the hymn “We Rise" at a memorial honoring Renee Good, who was fatally shot by an ICE officer, near the site of the shooting in Minneapolis, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026. (RNS photo/Jack Jenkins)

Jack Jenkins

January 9, 2026

RNS

MINNEAPOLIS (RNS) — Earlier this week, the intersection of 34th Street and Portland Avenue was a chaotic scene of violence and tears. A mangled maroon Honda Pilot sat crushed against a telephone pole as its driver, Renee Good, lay dying after being shot by a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent. Bystanders, including a woman who identified herself as Good’s wife, screamed and sobbed.

Days later, the vehicle and ICE agents are gone. But the tears are not, and neither is the outrage.

On Friday morning (Jan. 9), dozens of mourners and faith leaders gathered at the same intersection for an impromptu memorial — one of multiple in the area — for Good. As neighbors and dignitaries such as U.S. Sen. Tina Smith, D-Minn., shuffled carefully over a patch of ice stretching alongside the growing mountain of flowers, candles and photos, three clergy members belted a rendition of the hymn “We Rise.”

Good’s killing by a federal agent has kicked off a wave of protests across the country. And while President Donald Trump’s administration has insisted the ICE agent who shot her was acting in self-defense, Minnesotans gathered at Good’s memorial who saw video footage of the incident were unconvinced and frustrated by the continued actions of ICE and Department of Homeland Security agents enacting the president’s mass deportation agenda across the city.

“We’re gathered because somebody was murdered by agents of the government,” the Rev. Dana Neuhauser, a United Methodist minister who sang with the group, said in an interview. “But we’ve been showing up in a variety of ways because our neighbors are being snatched. Parents being snatched in front of the school.”

She added, “It’s all just too much, but my faith requires me to show up.”

People gather around a makeshift memorial honoring Renee Good, who was fatally shot by an ICE officer, near the site of the shooting in Minneapolis, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026. (RNS photo/Jack Jenkins)

Standing nearby was a man named James, who declined to have his last name published. James said he lives in the house directly in front of the memorial and witnessed the immediate aftermath of the shooting. He said he was angry about the government’s assessment of the shooting, which has included labeling Good as a domestic terrorist and accusing her of weaponizing her vehicle against an agent.

“She was not the problem here,” James said. “She is the victim 100%. And this community is a victim.”

A person of faith with a range of spiritual influences, James said he has tried to remain “strong for others” amid the outpouring of grief, but found himself profoundly moved when a group of faith leaders held a press conference in front of his house the day before.

“You could just see the raw emotion on their face, when these pastors and chaplains and everybody were speaking, and it started to get to me,” James said, his voice cracking.

Around the corner from the memorial, another group gathered in front of Park Avenue United Methodist Church, the nearest house of worship to the scene of the shooting. The Rev. Jennifer Ikoma-Motzko, a pastor at the church, opened what was described as a “solidarity service” by reflecting on her background as a Japanese American who grew up hearing stories of Japanese internment during World War II.

The Rev. Jennifer Ikoma-Motzko speaks during a solidarity service at Park Avenue United Methodist Church, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026, in Minneapolis. (RNS photo/Jack Jenkins)

Her family, Ikoma-Motzko said, “saw personally what happens when executive order, when government weaponizes fear against its own people.” She recalled how her grandmother would send her stories and even comic books about the experience of internment.

“It astounds me and it grieves me to carry out her legacy consistently year after year, and even today to see that same sort of fear and violence happening here in our communities,” Ikoma-Motzko said.

She was echoed by the faith leaders back at the memorial, such as the Rev. Ashley Horan, the vice president for programs and ministries at the Unitarian Universalist Association who also lives just a block from where Good was killed. Horan was one of several people who rushed to the scene shortly after the incident, live-streaming as bystanders confronted DHS officials who responded with tear gas and pepper spray.

“I’m here because this is our city, and this is how we show up,” she said. “We have always taken care of each other because we know that the government is not doing that for us.”

Horan said Good was reportedly operating as an “observer” when she was killed — a practice that has sprung up around the country since the president began his mass deportation campaign. Observers often follow and monitor ICE agents in public places, blowing whistles to alert nearby people and filming officials to document their activities.

It’s a practice taken up by a wide range of advocates — including, Horan said, clergy like herself.

“She could have been any of us,” Horan said, referring to Good.

Observers still appeared to be operating throughout Minneapolis on Friday. Earlier that morning, the Rev. Susie Hayward — a United Church of Christ pastor who was among those shoved by DHS officials and hit with pepper spray the day Good was killed (Jan. 7) — pointed out a person with binoculars standing on a street corner in a nearby neighborhood. The person, she said, was an observer attempting to identify ICE agents in their cars, as the enforcement officials often operate in unmarked vehicles.

Nearby at the Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport, faith leaders joined union members and advocates for a demonstration. Standing in front of a banner reading “Minnesotans were abducted here,” the Rev. Paul Graham, an Evangelical Lutheran Church of America pastor, condemned the detention and deportation of airport workers by ICE, as well as deportation flights operating out of the facility.

“Love of neighbor is essential for our communities to thrive and for us to live together as God intends,” Graham said. “The ICE activity in Minnesota is a violation of my faith as I understand it.”

He also demanded ICE leave the state of Minnesota “immediately,” and for the ICE agent who killed Good “to be held accountable.”

The Rev. Paul Graham speaks during a demonstration at Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026, in St. Paul, Minn. (RNS photo/Jack Jenkins)

“We call for peace and justice in our communities,” Graham said. Moments later, the airport group, which consisted of dozens of people, began singing “We Shall Overcome.”

Afterward, Graham talked with reporters alongside Rabbi Eva Cohen, who leads Or Emet, a local Humanistic Jewish synagogue.

“In Jewish tradition, when a person dies we say may their memory be a blessing,” Cohen said. “So thinking about Renee Good — a good person, a decent person, a mother, someone who cared about her community and standing up — may the loss of her life not be in vain. May her memory inspire us to continue to peacefully stand up for what is right.”

RELATED: How one conservative Christian family is pushing back against ICE

Cohen also said her young daughter, who was playing at her feet, was with her at the demonstration because of the actions of immigration agents. Schools in the city have been closed since Wednesday, when U.S. Border Patrol officers arrived at a local high school property and began tackling people and releasing chemical weapons on bystanders. According to Minnesota Public Radio, at least two school staff members were handcuffed during the incident.

“Many families of children at my daughter’s school are very frightened,” Cohen said.

Graham said raids at schools have impacted his daughter as well, who teaches first grade in the city. He said his daughter spent the day Good was killed “on lockdown” with her students and has personally observed people being detained.

“She witnessed a cafeteria worker hauled out of the school,” Graham said. “These things just should not be normalized, they’re not OK, and we need to keep saying that over and over and over again.”

Neighborliness is a lived theology in Minnesota

(RNS) — The simple concept of caring for those in your proximity holds religious resonance.

People gather around a makeshift memorial honoring Renee Good, who was fatally shot by an ICE officer the day before, near the site of the shooting in Minneapolis, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026. (AP Photo/John Locher)

January 9, 2026

RNS

(RNS) — “I realized it was that Renee Good, our kids are in school together,” read a text I received in the last 24 hours from a friend in our Minneapolis community. I did not know Renee personally, but I feel the pain and sadness that’s now a lasting part of our city.

That is precisely the point of the lived theology of neighborliness, something uniquely Minnesotan that presses us to show up for each other. I do not need to know you to love you and show compassion; knowing you are my neighbor is enough.

This interconnectedness is reflected in the highest levels of our state government. In a press conference yesterday, Gov. Tim Walz said, “I saw it last night, I saw it during George Floyd, I’ve seen it throughout our history, when things look really bleak, it was Minnesotans first who held that line for the nation … to rise up as neighbors, and simply say we can look out for one another.” He connected this bond of neighborliness as a cornerstone for a healthy, thriving democracy that holds us together when we differ and disagree.

The simple concept of caring for those in your proximity holds religious resonance. And even for atheist Minnesotans, it holds an ethic of care that encompasses the unknown neighbor.

The late sociologist Robert N. Bellah gives us a directive for charting a course as a nation: “A chance for another course, another role for America in the world, depends ultimately on the reform of our own culture. A culture of unfettered individualism combined with absolute world power is an explosive mixture. A few religious voices have been raised to say so. The question of the hour is whether our fellow citizens, much less our leaders, are ready to hear such voices.”

Minnesota has the highest number of refugees per capita in the U.S. This hospitality is based on theologies of welcoming the stranger, enacted by Christian and other religious relief services dedicated to resettling refugees who flee violence and persecution. It’s a familiar story, and a truly American one.

Taking a neighborly approach to helping is not dependent on the legal immigration status of any community member. Describing people as “illegal” creates a dehumanized class in which withholding basic human rights becomes the norm. In Minneapolis, our close-knit communities already know this. In fact, Renee Good moved to the South Minneapolis area because she was seeking community, and her community is grieving her collectively.

Our ability to create bonds of humanity creates an empathy grounded in action. Embodied empathy is the basis of activism — it’s when you put your body on the line in non-violent action to support the continued living of another. Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas tied human interaction to our ability to act together for the dignity of another.

We see this time and again with leaders coming together to bear witness to the human rights abuses against immigrants, who are, at their core, our neighbors. Examples abound of projects across the Twin Cities of people organizing to provide food for neighborhood children, offering accompaniment to immigration court and standing witness as people are detained. We are operating out of this common category of neighbor, and in this day and age of toxic division, the simple category of “humanity” holds people together and fills them with courage.

One of the famous sayings of Prophet Muhammad is, “He is not a believer whose stomach is full while his neighbor to his side is starving.” And in Islam and in many other religious traditions, we do not typecast the neighbor as having to represent one’s own religion, race, national origin or history. At an interfaith meeting about a month ago at a church, convened by a pastor and imam concerned about anti-Somali rhetoric, a rabbi said to our group, “I am here because what is happening to your community happened to me in the past, and my Jewish teachings pressed me to be here.”

People are showing up, across faith communities, caring for one another in material ways because they see the neighbor as someone who is in proximity. Yesterday, as I was checking in with faith leaders around the area, an imam expressed deep sympathy for Renee and her family. He did not know her, share her belief system nor reflect her ethnic heritage. None of those connections mattered, though. Tears have been flowing for her from every faith community and from people without a faith community. The site of her killing is now a sacred one.

Beyond Minnesota, I often say the “flyover” part of our country is leading on interfaith action and care because these states are places where you still know your neighbor. In them, interfaith relations are building what I call casserole (or hot-dish) hospitality. Maybe it’s a samosa or shawarma plate, but hosting, holding space for and being in community are natural, intentional parts of the Midwest culture and ethos.

People across our state and region have made the practice of neighborliness a way of life. Maybe we are a test case for the future of America — one in which we could choose a future based on compassion.

(Najeeba Syeed is the El-Hibri endowed chair and executive director of the Interfaith Institute at Augsburg University in Minneapolis. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)