Image by Egor Myznik.

The bombing of Guernica in 1937 unveiled weapons of mass destruction aimed at civilian populations. While Picasso’s famous painting depicting that event brought cubism and outrage together, Guernica marks a more critical narrative demarcation point – the beginning of current US military culture. Hitler and Mussolini’s targeting of a Basque town in 1937 to assist Generalissimo Francisco Franco in the quest to overthrow the republic employed the cutting edge of war technology. Saturation bombing of civilians would be a universal feature of the Second World War, but eventually the US would reinvent the psychology of warfare. Today the US runs a global empire founded almost exclusively on serial terrorism from the sky.

With the increased military capacity to impersonally erase thousands of lives – eliminating any physical contact between the perpetrator and the victim – war has become “decoupled” from consequences, from risks, from personal accountability, and, ultimately, from moral constraints. War, an event that once featured the profound intimacy of hand to hand combat, now can be pared down to statistical results on a ledger sheet, the costs and benefits of a business that outsources pain and sacrifice as a means of shutting down public opposition. The goal of US military power is to control foreign governments without paying for that control with sacrificed soldiers. This can happen by raining terror from the sky, committing genocide from above at little risk. The ultimate accomplishment of US military evolution is Gaza – a proxy war in which technology has turned war into demolition. Think of Gaza as a series of buildings being razed to allow for a new construction project.

When war becomes a matter of technological imbalance, a confrontation between a culture that has no access to weapons of mass destruction and one that has limitless capacity to exploit the means of obliteration, we have reached Gazan dimensions of absurdity. There is no war in Gaza in the traditional sense, just the carrying out of technical acts – mechanical deeds, the soulless behavior of industrial systems. That has been the goal of US military power since World War Two, when the US took over the task of violent expansion from the vanquished Nazi regime, and surrounded The Soviet Union (as Germany had once held Stalingrad under siege) with military bases.

The US aspired to exploit a monopoly of nuclear weapons after conducting in vivo experiments – Hiroshima and Nagasaki. With all the atomic warheads hoarded under a single flag, the US, under Harry Truman, aspired to channel the spirit of Guernica into a global hegemony. US military brass had teetered on the edge of fantasy and nightmare, to imagine not one, but dozens, even hundreds of nuclear strikes on The Soviet Union, reducing a great country, and a competing economic philosophy to utter rubble on an inconceivable scale. According to Russian journalist, Ekaterina Blinova:

“Between 1945 and the USSR’s first detonation of a nuclear device in 1949, the Pentagon developed at least nine nuclear war plans targeting Soviet Russia, according to US researchers Dr. Michio Kaku and Daniel Axelrod. In their book “To Win a Nuclear War: the Pentagon’s Secret War Plans,” based on declassified top secret documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, the researchers exposed the US military’s strategies to initiate a nuclear war with Russia.

The names given to these plans graphically portray their offensive purpose: Bushwhacker, Broiler, Sizzle, Shakedown, Offtackle, Dropshot, Trojan, Pincher, and Frolic. The US military knew the offensive nature of the job President Truman had ordered them to prepare for and had named their war plans accordingly,” remarked American scholar J.W. Smith (“The World’s Wasted Wealth 2”).

These “first-strike” plans developed by the Pentagon were aimed at destroying the USSR without any damage to the United States.”

The idea of one sided military destruction may have received a fatal and unexpected blow as the Soviets gained nuclear parity with surprising swiftness (creating our ongoing existential nuclear framework of mutually assured destruction), but the idea of controlling the world from the skies has been an inextinguishable driving force in US foreign policy. We saw this aspiration in General Curtis LeMay’s threat to “bomb Vietnam back to the stone age” – an undertaking that proved impossible, for war against defenseless villagers does not aim to destroy a nation militarily, it strives, rather, to exact human suffering for its own sake. The US leadership – habitually fond of hurling the word terrorist as a generic epithet – has used terrorism as an almost exclusive military default.

We normally think of terrorism as an equalizer for political organizations that have no capacity to wage war. A suicide bomber allows ISIS or Al Qaeda to intimidate western nations despite having an infinitesimal fraction of the military resources of their opponents. US terrorism raises a paradox – a country that has amassed more weaponry than any other still acts as though it has no military capability at all. In effect, the gargantuan US military indeed has almost no capacity to win wars – the US empire has become too vast to police, and the US public proved during the Vietnam War that it had no stomach to give up its sons for colonial adventures on the other side of the planet. Retired Lieutenant Colonel, William Astore explains the bizarre story of the US and its fetish for bombing:

This country’s propensity for believing that its ability to rain hellfire from the sky provides a winning methodology for its wars has proven to be a fantasy of our age. Whether in Korea in the early 1950s, Vietnam in the 1960s, or more recently in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, the U.S. may control the air, but that dominance simply hasn’t led to ultimate success. In the case of Afghanistan, weapons like the Mother of All Bombs, or MOAB (the most powerful non-nuclear bomb in the U.S. military’s arsenal), have been celebrated as game changers even when they change nothing. (Indeed, the Taliban only continues to grow stronger, as does the branch of the Islamic State in Afghanistan.) As is often the case when it comes to U.S. air power, such destruction leads neither to victory, nor closure of any sort; only to yet more destruction.”

One might see the repetitive ritual of US bombing – almost always deployed against dark skinned victims – as part of a mass extortion scheme. Imagine a kidnapper demanding ransom for a child and sending the tip of the child’s severed finger as proof that he means business. The world knows that the US means business when it comes to bombing. The American military often displays severed body parts – in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Iraq and Syria – and now, by proxy, in Gaza. The US controls the world, not by the usual colonial means of conquest and occupation, but by pure fear of the heavens that can open up on a whim unleashing bunker busters and napalm.

The last time the US won a war via destruction from the air was in 1945 when atomic weapons detonated over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Those terrible moments have been locked into the mindset of US masculinist prancing for eight decades. The prototypal episode unleashed a frightening aftershock of internal euphoria among top US brass that can be gleaned from a letter sent by Manhattan Project physicist, Louis Alvarez, to his young son Walter.

Alvarez was one of a few scientists wishing to see his handiwork in person, and he flew alongside “The Enola Gay” as a witness in a plane named “The Great Artiste.” He describes the blast as “awe-inspiring,” refers to his targets as “the Japs” and does not trouble himself with a single word of distress about the tens of thousands vaporized, burned, blinded, maimed and haunted by this dry run for the American military ego.

Alvarez and his son, Walter would later become famous for their theory proposing that a meteor strike wiped out the dinosaurs. One might speculate that the Chicxulub Meteor – the starring item in Alvarez’ famous theory – originated in the Nobel Prize winning physicist’s memory of Hiroshima. Legendary Princeton paleontologist, Gerta Keller (Keller, with her own improbable story, attributes the Dino demise to Deccan Traps volcanism), has fiercely argued against the Alvarez dinosaur extinction hypothesis, alleging that Louis Alvarez pushed his theory by bullying and threatening opponents with loss of tenure, but this tangent should not encourage us to see Alvarez as an outlier with hardened character flaws.

A far more toxic figure than Louis Alvarez – Donald Trump – invoked our shared horror with an unknowing boast about his ineffectual bombing of Iran last week:

“I don’t want to use an example of Hiroshima. I don’t want to use an example of Nagasaki, but that was essentially the same thing that ended that war.”

Trump, who had once bragged that he owned a bigger nuclear button than Kim Jong Un, offered evidence that the prototype of US air domination never strays from the minds of those driving US colonial expansion. Hiroshima and Nagasaki comprise America’s wet dream, and sustain the obsession with air warfare.

Trump’s ridiculous baiting of Iran to surrender after an ineffectual air strike rather suggests the phallic symbolism of bombs and planes – penis shaped objects that soar and “explode” (the Elizabethans of Shakespearian times used death as a vernacular term for orgasm). And that may be the point, as it is in America’s gun fetishism – a masculinist ritual of phallic power, for which the people of the world are an endless repository of collateral damage. It is no accident that Trump, the court confirmed rapist, the small handed sufferer of phallic uncertainty, should embrace bombing with such joyful, threatening satisfaction.

We all know that the whole world despises the United States, but we rather analyze and describe that hatred in whimsical terms – we flatter ourselves that we are merely dumb, boorish, deluded and full of ourselves, when, in fact, we collectively engage in mass murder as a reflexive expression of our global fantasies. We murder with an air of mass oblivion, reflecting, like Louis Alvarez, upon the awe-inspiring mushroom cloud without even pretending to imagine the bodies underneath the smoke.

It is quite a mistake to merely attribute our rage to exterminate as a byproduct of some sort of unresolved phallic insecurity. War and weapons are enormously profitable. Almost every city and town in the US provides a safe haven for the armaments industry and in my tiny home town of Northampton, Massachusetts we make the sensors that have helped destroy tens and tens of thousands of defenseless innocents in Gaza at a little factory on Prince Street operated by L3Harris. This factory makes the systems that may soon consume the entire globe and bring our species, and all others to an abrupt halt.

I should list the profits of L3 and Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrup Grumman and all the other icons of the military industrial complex that shake down the planet for every dime that the human race can possibly spare, but the astronomical totals are beside the point. The United States drives the world to hell in a handbasket with a fetish to rain down bombs from the sky. For my part, I picket my local death machine on Prince Street with two other elderly men and two younger women each Wednesday morning. I am not a crazy person who has any illusions about my actions – that might well be meaningless.

But if thousands would gaze into the tortured soul of America and see that L3Harris is the beating heart of our almost inevitable extinction, then our numbers would swell as they absolutely must. Every citizen of this cursed country has the task to bring the destroyer of the world to its senses. The very first priority is to upend the bomb dropping enterprise that feasts on profits and unacknowledged sexual compulsions.

This piece first appeared on Nobody’s Voice.

Phil Wilson is a retired mental health worker who has written for Common Dreams, CounterPunch, Resilience, Current Affairs, The Future Fire and The Hampshire Gazette. Phil’s writings are posted regularly at Nobody’s Voice.

We have observed on multiple occasions that Donald J. Trump is an unhinged, egomaniacal Caesarist who knows no limits to power. Indeed, it would appear that he believes himself to be the CEO of the world, bombing Iran last weekend for the good of mankind despite the fact that it poses no military threat whatsoever to the USA, as we amplified in Part 1; and now instructing world oil producers in Clint Eastwood fashion to “not even think about” failing to pump whatever it takes to compensate for any shortfall of supply that may result from his reckless and utterly unjustified blunderbuss attack on the second largest Persian Gulf producer.

For want of being misunderstood, the Donald even issued his warning in ALL CAPS. The Trump-O-Nomics economic con job just plain can’t stand oil above $70 per barrel!

“EVERYONE, KEEP OIL PRICES DOWN. I’M WATCHING! YOU’RE PLAYING RIGHT INTO THE HANDS OF THE ENEMY. DON’T DO IT!”

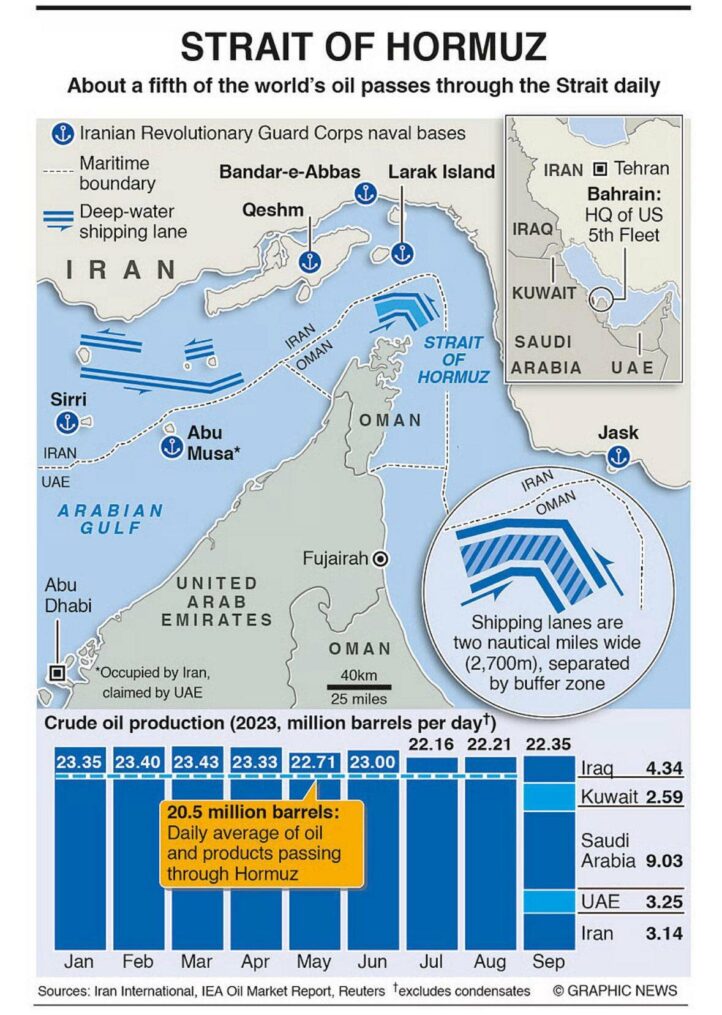

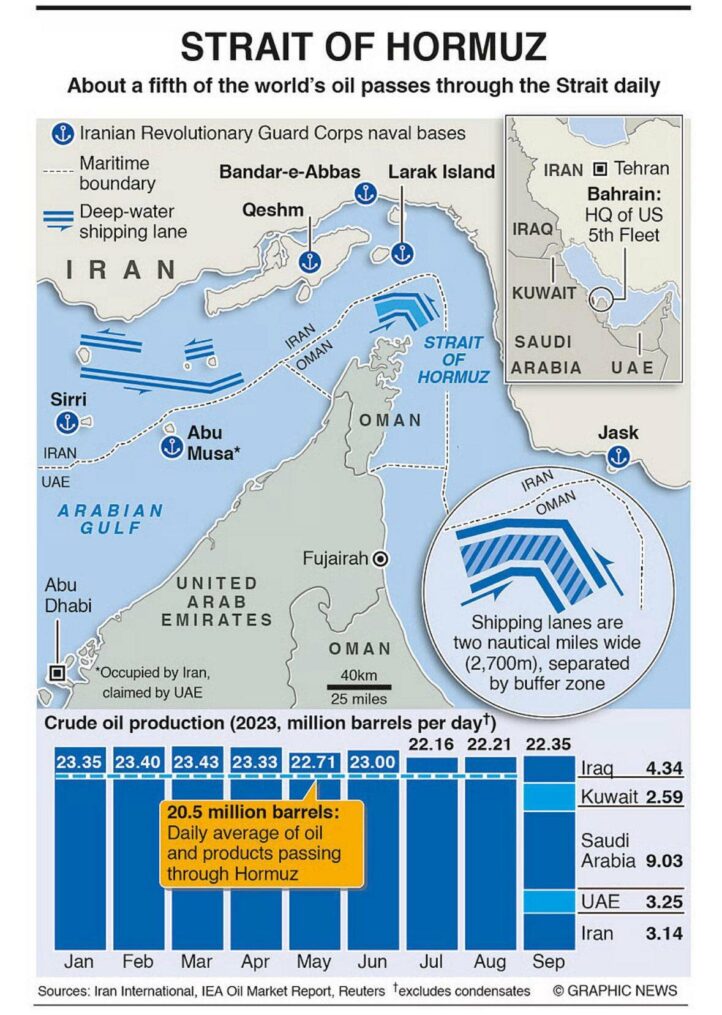

Well, Holy Moly, who made Donald Trump or any other president of the USA the petroleum czar of the planet? And besides, when you look at the slate of global oil producers virtually all the spare production capacity is chock-a-bloc inside the two-mile wide shipping lanes of the Strait of Hormuz – which his foolish bombing run put exactly in harms’ way.

Indeed, it might well be wondered who this ALL CAPS bellicosity is directed at. At the present time, 25 million barrels per day of petroleum (crude plus natural gas liquids) is produced at locations inside the narrow neck of the Strait of Hormuz, or one-quarter of the global supply. If Iranian production of 4.8 million barrels per day is withheld, or if tanker traffic through Hormuz slows sharply due to soaring insurance rates or cautionary behavior of tanker operators – six of whom have already performed abrupt U-turns at the Hormuz entrance in the last day or so – then who might the Donald be planning to threaten if they don’t open the taps on any idle capacity?

In fact, the most logical source of supply reduction would be Iran itself. According to Goldman Sachs, a 1.75 mb/d cutback by Iran, which would amount to just 35% of its current production, would raise the world oil price to $90 per barrel. So we suppose the Donald could send the bombers on a second Iranian run, this time as punishment for failing to produce the amount of oil demanded by the POTUS.

Failing that “option”, if the Saudis or the UAE – the two Gulf producers with material spare capacity – decided out of an abundance of caution to take the price windfall and hold production constant, exactly how would the Donald make good on the above ALL CAPS threat? Bomb them, too?

Moreover, outside the Hormuz choke point the five largest non-US producers are Russia, China, Canada, Mexico and Nigeria, which between them account for 25.2 mb/d or actually slightly more than the Persian Gulf producers. But given all the barking that the Donald has already done at the first four of these during just five months in office – the mega-tariff card has already been played – we are not sure that even the Donald would be up for sending the B-2s.

Of course, there is always “drill, baby drill” in the USA. Yet at nearly 22 million barrels per day – including 13.5 mb/d of crude oil and shale plus another 8 mb/d of natural gas liquids, lease condensates and refinery gains – US production of petroleum liquids is already at the tippy-top of the historic charts and at near-term industry capacity. For example, during the last showdown with Iran in 2015, when the JCPOA was negotiated, USA liquid petroleum production was one-third lower at 14.3 mb/d.

In short, the above ALL CAPS post from this morning is just one more indication that the Donald is sliding by the seat of his ample britches as he huffs and puffs his way right into another self-inflicted Persian Gulf oil crisis. That’s because any prolongation of the War on Iran jointly initiated by the world’s two great megalomaniacs – Donald Trump and Bibi Netanyahu – has very serious potential to spill-over into an interruption of the 25.0 mb/d of petroleum that flows through the Strait of Hormuz.

The latter could readily happen, of course, whether owing to soaring insurance rates, tanker diversions or a break-out of actual kinetic conflict if tit-for-tat exchanges – like today’s Iranian attack on the US base in Qatar – should go astray. Given the very high short-run inelasticity of petroleum demand, any serious supply disruption – even 10% of the throughput at Hormuz – would generate $100+ per barrel oil prices in a heartbeat.

And then, of course, the madman who makes no never mind about the Constitution’s delegation of the war powers to the Congress, would respond with an all out war on Iran. And do so for every reason of egomaniacal satisfaction and no reason of homeland security whatsoever.

Current Global Petroleum Production

Petroleum Production | Oil (mb/d)

---------------------|----------

Bahrain | 0.2

Iran | 4.8

Iraq | 4.5

Kuwait | 2.7

Qatar | 1.8

Saudi Arabia | 11.0

UAE | 4.3

Persian Gulf | 25.3

USA | 21.9

Russia | 10.8

China | 5.3

Canada | 5.6

Mexico | 2.0

Nigeria | 1.5

Rest of World | 24.6

Global Total | 97.0

Indeed, the Donald’s unjustified rampage against Iran has already gone so far afield that his henchmen in the Administration are demanding that other major global powers, whether they have a beef with Tehran or not, must now muscle the Iranians into abject acquiescence to Washington’s attack on their sovereignty. Or as Bibi Netanyahu’s emissary at the US State Department said,

“I would encourage the Chinese government in Beijing to call them about that, because they heavily depend on the Straits of Hormuz for their oil,” Rubio replied.

“But other countries should be looking at that as well,” he added. “It would hurt other countries’ economies a lot worse than ours. It would be, I think, a massive escalation that would merit a response not just by us but from others.”

That’s right. Washington’s utterly unnecessary attacks now threatens hundreds of billions – even trillions – of economic harm to global oil importers, but it’s their job to clear up the mess!

This is so absurd as to put us in mind of the 12-year who killed both of his parents, and then threw himself upon the mercy of the court on the grounds that he was an orphan!

As we insisted in Part 1, there is absolutely zero reason for attacking Iran because with or without uranium enrichment–or even HEU (highly enriched uranium) for a bomb – Iran is no threat whatsoever to the Homeland Security of America. Indeed, in the very worst imaginable case – where Tehran manages to fabricate a primitive nuclear bomb or two – they have nothing remotely capable of delivering it to the US homeland: To wit, Iran’s longest range missile has an arc of 2,000 kilometers at maximum, but the nearest US shore is 10,000 kilometers from Tehran.

To be sure, the world – including the Iranian people themselves – would be far better off if Iran or any other current nonnuclear country never got the bomb. The irony, however, is that Iran does not want the bomb, but it is being driven in that direction by the relentless pressures, demonizations and attacks from the War Capital of the World on the banks of the Potomac and its accomplices in Israel.

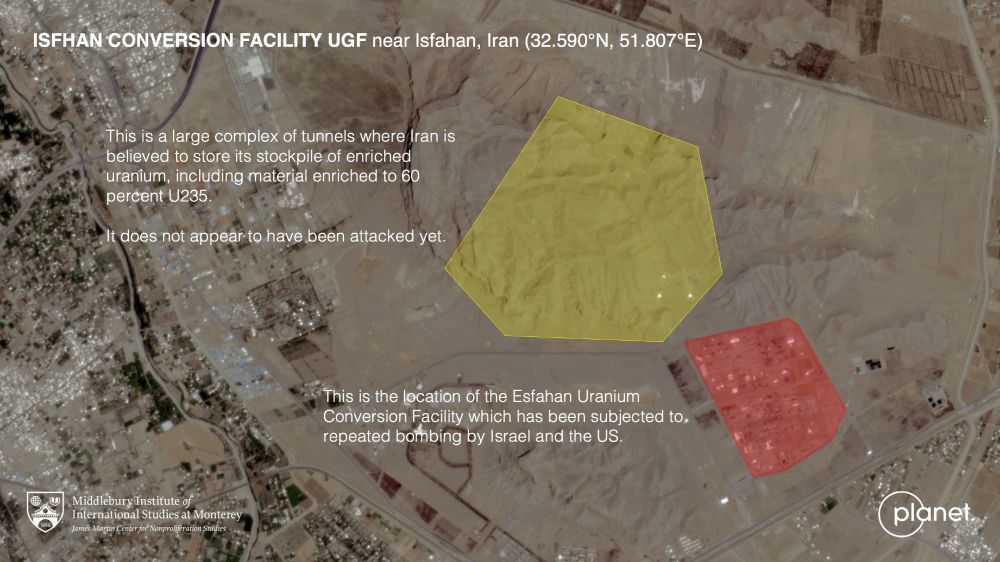

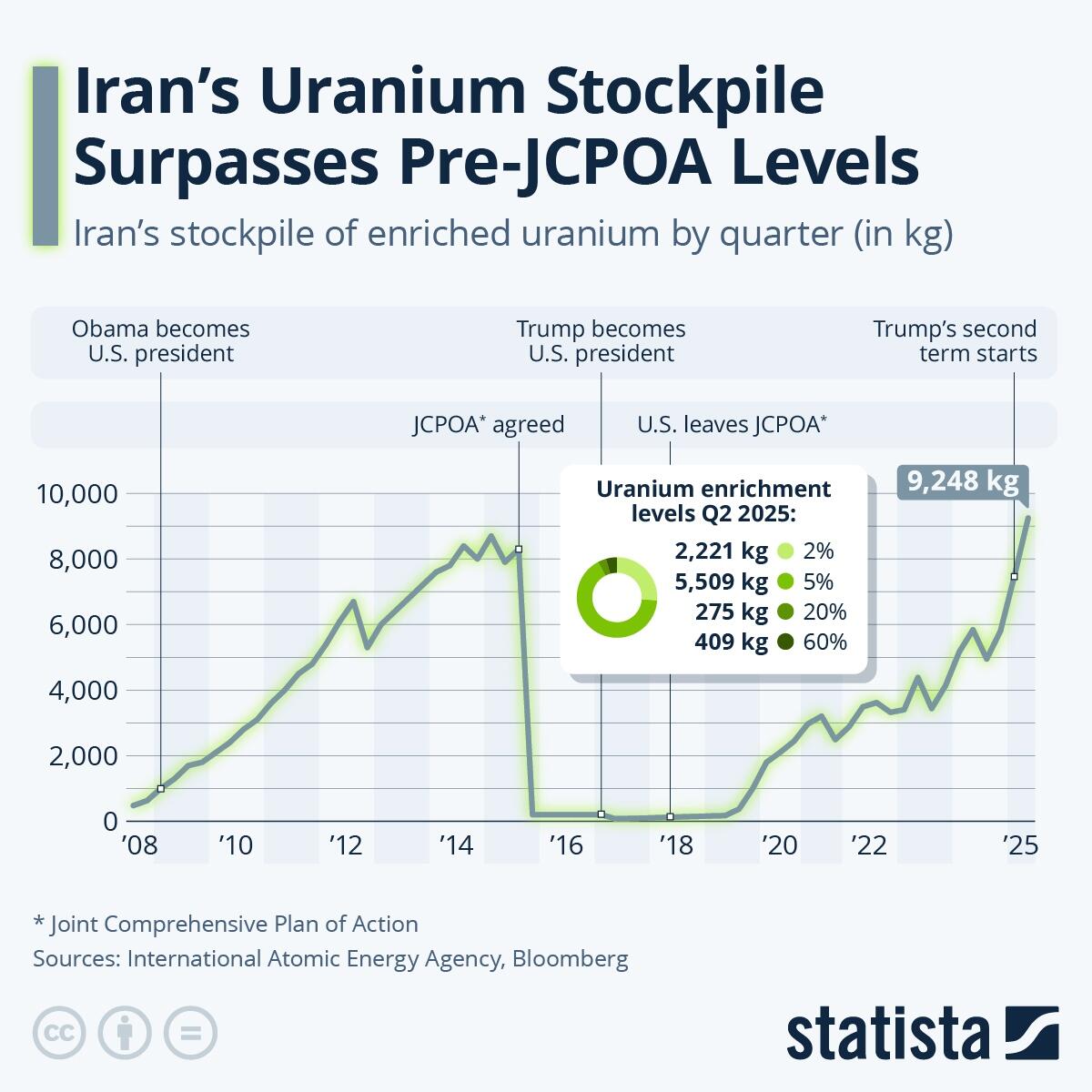

For want of doubt, just consider that by all present accounts, very little if any of the 409 kilograms of 60% enriched uranium that Iran was alleged to posses was destroyed by the Saturday night bombing. And it’s also likely that most of Iran’s modern high yield IR-6 centrifuges were not destroyed deep in their mountain bunkers at Fordow, as well.

As to the near bomb-grade material, arms control expert Jeffrey Lewis showed this morning that the 400+ Kg of 60% material had been moved to underground tunnels near the Isfahan Uranium Conversion Facility. Despite extensive Israeli and US attacks the facility, there does not seem to have been any effort to destroy these tunnels or the material that was in them.

In any event, as a NPT (nonproliferation treaty) signatory and operator of a 3,000 megawatt civilian nuclear reactor at Bushehr, Iran was allowed to have the 7,582 kilograms of civilian reactor grade enriched uranium that the IAEA last certified, as well as the 1,257 kilograms of medical grade uranium (20%).

What was really up for debate was just the 409 kilograms of 60% enriched material in its possession that could be spun to 90% weapons grade in a relatively short time. But for crying out loud, it is goddamn obvious to anyone not looking for an excuse for war that Iran had produced this material as a bargaining chip in order to get a new nuke deal with Washington, and thereby pave the way for lifting the brutal and demented economic sanctions that Washington has again imposed on Iran.

Iran’s Enriched Uranium Stockpiles As Of May 2025

Stockpile Component |Amount (kg) |Enrichment

------------------------|------------|----------

60% Enriched |409 |60%

20% Enriched (Est.) |1257 |20%

Balance (Mostly 3.5–5%) |7582 |2–5%

Total |9247 |Mixed

The proof of the bargaining chip pudding could not be more evident in the graph below. During the 10-year run-up to the 2015 nuke deal with the Obama Administration, the Iranians increased their enriched uranium stock piles to just slightly below the current level, to about 9,000 kilograms. But in an almost mirror image of the present, only about 350 kilograms of that material was enriched to the 60% purity level or the threshold of weapons grade HEUs.

That is to say, it was generated as a bargaining chip, and that was exactly its fate. Upon activation of the JCPOA in 2015, all of the 60% material was destroyed as certified by the IAEA. At the same time, the total stockpile of civilian grade material was also reduced by 97% to de minimis working levels, as further certified by the IAEA. Indeed, Iran ended up retaining only 300 kilograms of its 9,000 kilogram stockpile – an amount that could have been readily stored in the Donald’s wine cellar at Mar-a-Lago.

As it happened, of course, the Donald recklessly canceled the deal in May 2018 on the grounds that it had to be a bad deal by definition because he didn’t negotiate it. Of course, that foolish move only caused the Iranians to restart the stockpiling process yet again, as is so explicitly depicted by the green line in the graph below.

The irony, therefore, is that after the Donald’s feckless bombing campaign the Iranians likely have close to 100% of the 9,248 kilograms (including the 409 Kg of 60% material) held last week still in tact. That’s based on pretty convincing satellite photos showing that all of the Donald’s amateur “art of the deal” head fakery about “two weeks to decide” on the bombing enabled the Iranians to drive trucks up to the Nantanz and Fordow facilities and remove the stockpiles to safe sites elsewhere.

Stated differently, Obama negotiated the Iran enriched stockpile to down by about 97%, while the Donald bombed roughly the same level of stockpile from 9,000+ kilograms to, well @ 9,000 kilograms!

That same is likely true for the halls of centrifuges at Nantanz and Fordow. Under the 2015 deal, Iran had agreed to reduce the number of centrifuges by 70% from 20,000 to 6,000 and actually did so after the deal took effect. Moreover, it effective enrichment capacity had been reduced by significantly more because the remaining Natanz centrifuges consisted exclusively of its most rudimentary, outdated equipment—that is, first-generation IR-1 knockoffs of 1970s European models.

Not only was Iran not allowed to build or develop newer higher yield centrifuge models, but even the old slow-pokes remaining were permitted to enrich uranium to a limit of only 3.75% purity. That is to say, to the generation of fissile material for power plants that is not remotely capable of reaching bomb grade concentrations of 90%.

Equally importantly, the agreement eliminated enrichment activity entirely at Fordow. The latter was Iran’s only truly advanced, hardened site that could withstand an onslaught of Israeli bombs or US bunker busters, and it was agreed that zero enrichment activity would take place there, subject to full IAEA inspection.

Instead, Fordow became a small time underground science lab devoted to medical isotope research and was crawling with international inspectors. In effectively decommissioning Fordow and thereby eliminating any capacity to cheat – what Iran got in return was at best a fig leave of salve for its national pride.

That is, again, until Donald Trump ixnayed the deal that the Obama team had so painstakingly negotiated. Subsequently, of course, the Iranians restarted enrichment activities at Fordow, and instead of zero slow-poke IR-1 centrifuges, it installed a phalanx of high speed IR-60 models.

And yet, and yet. The dust still have not settled on the receipts from Friday’s nights bomb-a-thon, but there is every indication that it did not achieve the 70% reduction in centrifuge machines obtained peacefully in the 2015 deal.

Nor is the tiresome neocon-Israeli claim that the JCPOA was fatally defective persuasive in the slightest. That’s just Warfare State propaganda, repeated over and over by the subservient corporate press.

For instance, take the case of the heavy water reactor at Arak. For years, the War Party had falsely argued because “plutonium”. That is, the civilian nuclear reactor being built there was of Canadian “heavy water” design rather than GE or Westinghouse “light water” model. Accordingly, when finished it would have generated plutonium as a waste product rather than conventional spent nuclear fuel rods.

In truth, the Iranians couldn’t have bombed a beehive with the Arak plutonium because you need a reprocessing plant to convert it into bomb grade material. Needless to say, Iran had no such plant, no plan to build one, and no prospect for getting the requisite technology and equipment.

But even that bogeyman was dispatched by the Obama nuke deal that the Donald saw fit to shit can the first time around. The 2015 deal required Iran to destroy or export the heavy water reactor core of its existing plant and replace it with a core that cannot produce material which can be reprocessed into weapons grade plutonium. All of these requirements were subject to rigorous international inspection and, in fact, were actually complied with before Trump cancelled the deal.

Of course, Iran’s reward for compliance was that Israel bombed the Arak facility during last week’s raids, apparently to destroy a plutonium source that had already been dismantled. Perhaps that was just to make sure… that Iran would never want to negotiate with Washington again.

Beyond that, Iran had also agreed to and had complied with a robust program of inspections to prevent smuggling of materials into the country to illicit sites outside of the framework facilities. That encompassed imports of nuclear fuel cycle equipment and materials, including so-called “dual use” items which are essentially civilian imports that could be repurposed to nuclear uses, even peaceful domestic power generation.

In short, even a Houdini could not have secretly broken-out of the box contained in the 2015 agreement and then confronted the world with some kind of fait accompli threat to use the bomb.

To do so would have required diversion of thousands of tons of domestically produced or imported uranium and the illicit milling and upgrading of such material at secret fuel preparation plants. It would also have involved the secret construction of new, hidden enrichment operations of such massive scale that they could house more than 10,000 new centrifuges. It would have also required the building of these massive spinning arrays from tens of thousands of components smuggled into the country and transported to remote hidden enrichment operations – all undetected by the massive complex of spy satellites overhead and covert US and Israeli intelligence agency operatives on the ground in Iran.

Finally, it would have required the activation from scratch of a weaponization program which has been dormant according to the US National Intelligence Estimates (NIEs) for more than a decade. And then, that the Iranian regime – after cobbling together one or two bombs without testing them or their launch vehicles – would nevertheless have been willing to threaten to use them sight unseen.

So what we had in the JCPOA was an end to any prospect that the Iranians would abandon the Ayatollah’s own fatwa against nuclear weaponization. There was also zero 60% enriched material left; stockpiles of permitted enriched uranium were reduced to de minimis working levels; and an airtight international inspection regime was in place. They only thing left was a residual enrichment capacity to supply the Bushehr nuclear power plant with enriched uranium from an Iran based source.

And, indeed, after several decades of drastic economic sanctions and periodic military attacks by both Israel and Washington, why would the Iranians not insist on having their own enrichment capacity, as is guaranteed to signatories by the NPT in any event? Otherwise, Bushehr could have been shutdown at whim by a Washington fatwa against enriched uranium exports to Iran.

What the Donald has single-handed accomplished in his two turns at bat, therefore, is to replace that workable JCPOA arrangement with an Iranian government that now more than ever will endeavor to have a nuclear bomb insurance policy. That is, Iran still has plenty of enriched uranium and probably a goodly hall full of centrifuges. It also has a supreme leader in the Ayatollah, who, if not actually dead, may be thanking his lucky stars that he did not receive the 2025 Muammar Gaddafi reward for trying to cooperate with Washington in yet another round of negotiations after the JCPOA double-cross – even as the Gaddafi treatment was bestowed upon his chief negotiator and top generals by the Donald’s confederates in Israel.

And this complete madness gets us to the real issue underlying the Donald’s current unhinged rampage. To wit, the USA should not even posses military capacities and offensive weapons like the bunker busters used last weekend by the dangerous cowboy currently domiciled in the Oval Office.

What we have going is now an extreme version of “kill them from the sky warfare” that Sunday afternoon warriors have been advocating ever since the infantry butchery of Vietnam. Indeed, from JD Vance on down the talking point is no boots on the ground – we will just keep pursuing “peace through strength” via raining lethal ordnance from the sky via bunker busters when necessary or waves of Tomahawk cruise missiles, from safe launch hideaways below the surface.

The issue of whether this kind of bloodless warfare (on our side) can actually succeed militarily is an open question and a debate for another time. But here’s the thing. We don’t need bunker busters to effect an invincible triad strategic deterrent because the proven logic and efficacy of MAD (mutually assured destruction) is that the certainty of a devastating anti-city retaliation stops an attack before it happens. Taking out the other side’s ICBM’s with bunker busters, in fact, would destabilize the equation and endanger the deterrence and peace because by design they would function as counter-force weapons in the strategic nuclear arena.

As for an ironclad defense of the American homeland from conventional military attack, bunker busters are useless. What you need, instead, is fusillades of drones, cruise missiles, fighter jets and attack submarines stationed in the American Homeland to protect the shorelines and airspace from conventional military invasion.

That is to say, the War Capital of the World bivouacked on the Potomac has outfitted the Oval Office with a War Machine that is mainly designed for the pursuit of Empire, not the maintenance of Homeland Security. And now the American people have mistakenly elected a brash, ill-informed Caesarist, whose unquenchable ego is bound and determined to use them.

David Stockman was a two-term Congressman from Michigan. He was also the Director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Ronald Reagan. After leaving the White House, Stockman had a 20-year career on Wall Street. He’s the author of three books, The Triumph of Politics: Why the Reagan Revolution Failed, The Great Deformation: The Corruption of Capitalism in America, TRUMPED! A Nation on the Brink of Ruin… And How to Bring It Back, and the recently released Great Money Bubble: Protect Yourself From The Coming Inflation Storm. He also is founder of David Stockman’s Contra Corner and David Stockman’s Bubble Finance Trader.