Bassoe: Shipyard Financiers Face $15.2 Bil Newbuild Drilling Rig Loss

They built them and no one ever came. Now shipyards need to do something other than wait if they want to solve their newbuild rig problem.

It’s 2019, the offshore rig scene is ramping up after a long and difficult downturn and newbuilds are finally leaving shipyards. Cue 2020, Coronavirus and a new oil price mess. There are still 69 newbuilds in yards and 65 of them, estimated by Bassoe Rig Values to be now worth approximately $6.2 billion, have nowhere to go. During the offshore rig newbuilding boom, which commenced around 10 years ago now, far more rigs were ordered, many on speculation, than were proven to be needed. Fast forward to 2020 and there is still a glut of units awaiting delivery from yards with little-to-no sale or work prospects in sight.

Data from Bassoe Analytics shows that there are 43 jackups, 18 drillships and 8 semisubs still classed as “under construction” today, though many of these have had deliveries deferred year after year in hopes that they will have brighter prospects to get a contract in a few years when the market recovers. Unfortunately, this has been the plan for the best part of a decade for some rig owners and now that we have escaped one downturn just to be met by a second means that little will change near term. Oil price, near-term demand and dayrates are all struggling and until these improve, newbuild sale and contracting activity will remain muted.

Do any of these rigs have work to go to?

Between the beginning of 2019 and mid-October 2020, 40 units were delivered thanks to some improvement in global oil market fundamentals. The majority of these were jackups, which were put to work in the Middle East, Mexico or China; meanwhile five harsh-environment semisubs were successfully contracted on long-term commitments in Norway plus a further semisub was contracted for work in Chinese waters. Only two drillships were delivered during the period, both Sonadrill units, with just one securing work in Angolan waters.

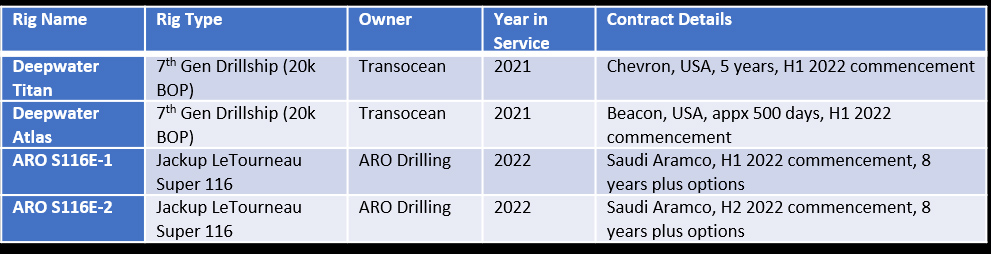

Figure 1: Newbuild rigs with contracts in place (Data from Bassoe Analytics)

As can be seen in Figure 1, only four of the 69 offshore rigs currently in shipyards have known future contracts in place: two are Transocean managed 20k BOP drillships, which will be utilized under long-term deals in the US Gulf of Mexico, and the other two are newbuild jackups ordered by ARO Drilling specifically for long-term deals with Saudi Aramco.

Who is responsible for all this excess tonnage?

Most of the companies originally responsible for these newbuilds have defaulted on their orders and walked away. That does not necessarily mean that it was their fault. When everyone wanted to order a new rig, circa 2010, shipyards enabled buyers by offering low-risk terms. The original buyers were hurt the least out of all this and the shipyards have been left holding assets that nobody wants.

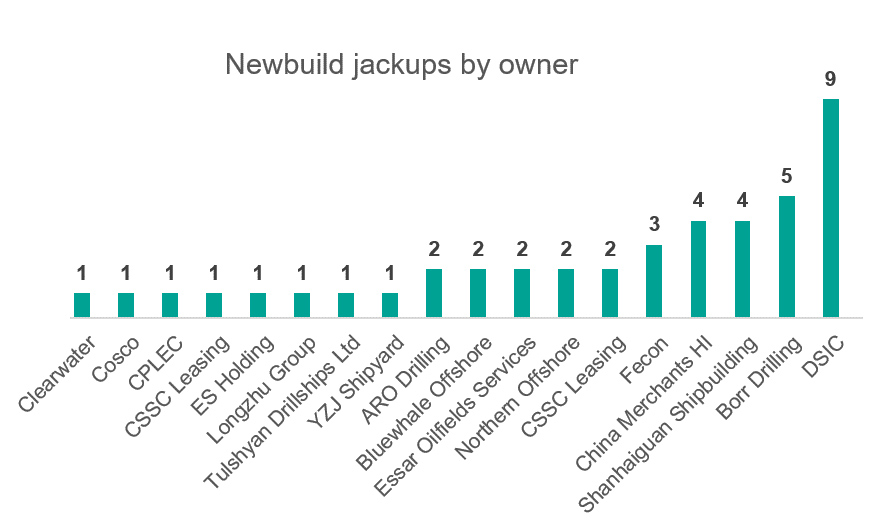

As has been the norm in the past, newbuild jackup ownership remains fragmented especially in comparison to floating rigs (see Figure 2). There are still 18 different “owners” within the newbuild jackup segment, with Chinese companies still essentially in control of the market. Like jackup ownership, the spread of newbuilds within shipyards is also disjointed with these 43 jackups spread across 14 different yards.

Figure 2: Newbuild jackups by owner (Data from Bassoe Analytics)

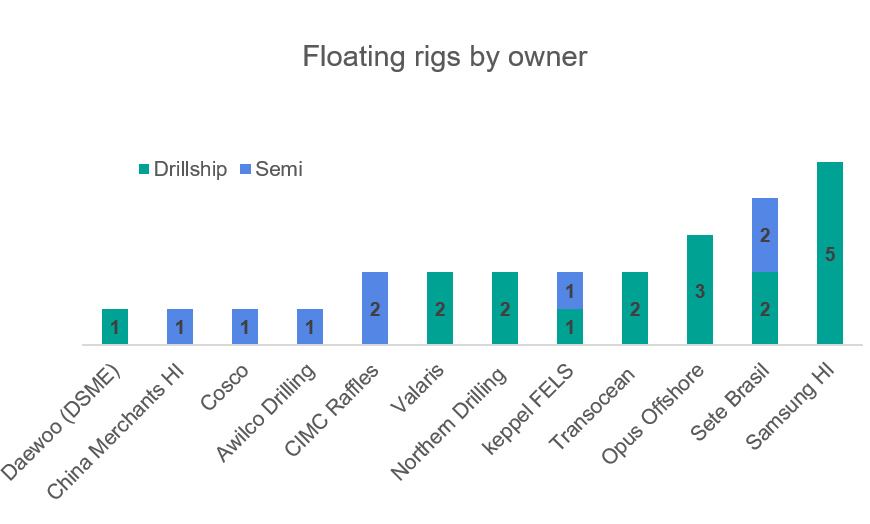

On the deepwater side of the market, drillships are the main cause for concern with more than double the amount marooned in comparison to semisubs (see Figure 3). The main reason behind this split is that many of the semisub newbuilds were designed for the Norwegian Continental Shelf, a market that has been doing relatively well, therefore yards managed to find new owners for these prior to 2020. It is now mainly benign floaters that are left in the yards. Most of these drillships were originally ordered by drilling contractors such as Seadrill, Ocean Rig, Pacific Drilling which, when faced with a depressed market and lack of demand during the last oil downturn, canceled construction contracts with yards.

Figure 3: Newbuild floating rigs by owner (Data from Bassoe Analytics)

Many shipyards are now under huge financial strain after owners backed out of contracts, leaving them to finance and finish construction work following a nosedive in drilling demand. Yards have been forced into the awkward position of having to build, own, and pay to maintain these assets.

What are the options going forward?

There are some companies which have been formed based on rescuing and managing these abandoned rigs, with SinoOcean being one of the most successful of late in the jackup segment. Perhaps more of the excess jackup tonnage will be brought under the wing of such companies, some will may be picked up by COSL for work in Chinese waters, while others could still be secured on bareboat leasing agreements which had been a growing trend until COVID and the oil price crash. Shelf Drilling, for example, recently canceled bareboat agreements with CMHI for two jackups.

One potential solution for shipyards would be to consider upgrading some of these rigs to cater to a growing trend towards “greener” drilling capabilities. This could make them more attractive to potential buyers and help to recover some of their loses. However, this would mean requiring more funding and not many yards would be open to risking further loses. However, yards that at least start investigating this could end up better off than the alternative.

The other options going forward are quite simple. Yards can keep holding onto these rigs, digging a deeper financial pit whilst hoping for a miracle upturn in the market; they can bite the bullet and try to sell assets while taking a massive financial loss; or a final option (and one that is becoming increasingly likely) is that some of these newbuilds could be scrapped before ever being put to work. Shipyards cannot keep stranded assets forever and now that many of these units are likely to have been written down, and with no market improvement in sight, it is probable that they will shortly attempt to offload rigs. Keppel Corp recently announced that it is considering divesting “non-core” assets such as drilling rigs as part of a new asset-light strategy. We believe that this is just start of many more such announcements to come.

Bassoe Analytics estimates that the original order value of these 65 remaining rigs would have been in the arena of $21.4 billion and when compared to our current estimated value of just $6.2 billion this already shows a brutal loss of over $15.2 billion for shipyards. To make matters worse, if yards start offloading newbuilds just to get rid of them, rig values may fall further. As reported in our last article, Ending offshore rig owners’ bankruptcy nightmare requires a lot more scrapping, these dormant rigs are all part of a bigger global oversupply problem in the offshore rig market. Until we witness a mass scrapping of old tonnage to make room for the new, these dormant rigs will likely continue to sit idly awaiting maiden charters that may never come.

This article is reprinted courtesy of Bassoe Analytics and it may be found in its original form here.

The Many Types of Capitalist Economic Anarchy

[This is a brief essay against the notion that there is only one kind of capitalist economic anarchy. I submitted it to the RCP*** in 1983 under the title "On State Capitalist Economic Anarchy". I received no response from them.]

The current discussion on the nature of the Soviet Union is an important one. But as an RCP member has pointed out to me, it is not simply a matter of arguing for one existing line against all other lines—it also includes the necessity of further developing our understanding of the question. Though I respect the contribution made by the old Revolutionary Union publication, Red Papers 7, as well as the more recent writings of the RCP on the subject, the present situation demands a still deeper analysis.

In this essay I would like to raise just one particular issue from among the many that need to be discussed—that of the existence and types of economic anarchy under capitalism, and under state capitalism in particular.

One of the main themes of Engels' work Anti-Dühring[1] is that under capitalism "anarchy of social production prevails" [p. 350] and that under socialism "the anarchy within social production is replaced by consciously planned organization" [p. 366]. He also says that

In proportion as the anarchy of social production vanishes, the political authority of the state dies away. Men, at last masters of their own mode of social organization, consequently become at the same time masters of nature, masters of themselves—free. [p. 369] |

I agree with Engels on these points—even the last one which could be taken by some to imply support for the infamous "theory of the productive forces" (though I do not read it that way). But if these points are even generally correct, it follows that you should be able to decide whether a society is capitalist or socialist by deciding if it can still be characterized by anarchy in its social production, and by whether such anarchy as does exist is decreasing or not.

(This is an economic test of socialism as opposed to a political test; and actually socialism is both a political and economic system. However I believe that these things are so interrelated that sufficient tests of either kind can be constructed and that they will not lead to opposite conclusions. In the present case, for example, it seems to me that the only way there could possibly be an absence of economic anarchy, or even a progressive diminution of economic anarchy in a society, is if the proletariat controlled that society... but this is jumping ahead in the argument.)

In pursuing this line of inquiry, then, the key question becomes: "In what does the socio-economic anarchy of capitalist production consist?" The answer to this question is that the anarchy of capitalist production is manifested in many ways, some of which are more important than others. All of these derive, however, from one basic contradiction in capitalist production, a contradiction so important in fact that it is often called the fundamental contradiction of capitalism: This is, as Engels expressed it, "the contradiction between social production and capitalist appropriation" [p. 349]. Let us then proceed to discuss some of the ways in which this contradiction leads to capitalist economic anarchy.

First, and most important, the fundamental contradiction leads to economic crises of overproduction. As is well known, this "overproduction" is not in relation to the material needs of the people, but rather in relation to what can be sold. If anything is economic anarchy it is the quintessential capitalist phenomenon of starvation and want in the midst of a mountain of "excess" goods which cannot be disposed of profitably. Of course the explication of these crises of overproduction can get quite complicated, as many subsidiary contradictions are involved. The whole of Marx's Capital is in effect the detailed story of how this all works. (This is why those who point to any single argument in Capital as being Marx's "theory of economic crises" are hopelessly off the mark.)

[Note added on 8/12/98: I've partially changed my mind on this point. It is not an appropriate response to someone seeking a short explanation of capitalist economic crises to say "go read Capital". The essential features of any process can be summarized briefly, or relatively briefly. But it is true that the essential features of capitalist economic crises are still somewhat complex. This is why Marx's dialectical explication of them is the best way to proceed.]

A second form of capitalist economic anarchy is the anarchy among the various capitalist enterprises. Each enterprise may attempt to organize its production rationally, but—traditionally at least—that same rational planning did not exist overall. There is no denying that this is an important type of economic anarchy, and it is also true that it can play a role in the development of overproduction crises. However, with the advent of monopoly capitalism this particular form of economic anarchy has become relatively less important than it used to be. For one thing, there is the widespread development of vertical integration of production within corporations, and the equally important closer integration of production between companies and their outside suppliers which has often gone so far as to allow "just-in-time" arrival of parts from other companies (in order to avoid large parts inventories). From the standpoint of rational planning of production it often no longer makes any real difference if the parts come from a different company, or from another factory or division of the same company.

For another thing, there are now generally only a small number of producers of particular commodities, and it is easier for them to divide up the market and hence impose at least a degree of rational planning among the various enterprises. Often this has even gone to the point of formal production cartels, though in the U.S. it is typically done through secret (illegal) agreements and implicit "understandings". And more important by far, there now exists the phenomenon of state capitalism of the Soviet variety, under which formal production plans are developed for the whole economy (even if they are to some extent a farce!). This does not completely eliminate the anarchy among Soviet production enterprises, but it certainly greatly reduces this type of anarchy.

Engels remarked that "The contradiction between social production and capitalist appropriation reproduces itself as the antagonism between the organization of production in the individual factory and the anarchy of production in society as a whole" [p. 352, emphasis in original]. While this is literally true, it is possible to read Engels here as saying that this is the only way that anarchy is manifested from the fundamental contradiction. I don't think Engels is saying this, but if he is, as much as I admire him, I have to say that he is wrong on this point. In any case, those who believe that the anarchy in capitalist production consists mainly (or entirely) of anarchy among capitalist enterprises are very much mistaken, as are those who believe that the fundamental contradiction must of necessity lead to the development of crises of overproduction through the exclusive medium of inter-enterprise anarchy.

It is easy to see why certain people today might be attracted to these views, however. For if the anarchy of capitalism derives solely (or even primarily) from the anarchy among competing enterprises, all that is necessary to eliminate this anarchy is to institute an overall state economic plan. State capitalism then becomes free (or largely free) of economic anarchy, they suppose. The Soviet revisionists repeatedly state that economic crises do not and cannot occur in the Soviet Union because of the existence of their overall economic plans. The fact that they continue to trumpet these comments at the same time as their economy sinks deeper into stagnation and crisis vastly amuses us, of course.

A third kind of capitalist economic anarchy is the anarchy which exists within capitalist enterprises. Marx and Engels often refer to the "social production" within each enterprise, and of course they even contrast this with the anarchy of production among the various capitalist enterprises. But anybody who has ever worked for a large corporation has, I am sure, seen enormous waste, disorganization, bad planning (or the partial absence of planning), and the like. In fact the "socialized production" of the capitalist workplace is really only semi-socialized and could be greatly improved upon in a more completely socialized enterprise controlled by the workers. Social production under capitalism is far from perfect because (for one important reason among many) society is split into classes and it is not in the interests of the workers to work harmoniously according to the production plans of the capitalists. Many workers know this quite well, at one level of consciousness or another.

Paradoxically, one of the factors leading to economic anarchy within corporations is a bureaucratic over-centralization! Any complex entity (be it a living organism or an economy) needs a dialectical balance between centralism and decentralism. Too much central control of production leads to a situation where some small dislocation somewhere cannot be quickly and readily compensated for, resulting in disruptive chain reactions. Of course this sort of thing is particularly characteristic of the Soviet economy, which comes close to being "one big bureaucratic corporation".

A fourth kind of capitalist economic anarchy is the anarchy which exists among capitalist countries, including that among the various state capitalist countries. This is, in a sense, the international reproduction of the older type of economic anarchy among individual enterprises within a single country. The importance of this form of anarchy has of course grown immensely with the advent of imperialism.

As long as capitalism exists all of the many types of capitalist economic anarchy will continue to exist, to one extent or another. And they all will continue to play a part in the development of overproduction crises. But the primary cause of crises of overproduction derives directly from the fundamental contradiction of capitalism (between social production and private appropriation), and these crises do not require the existence of any other type of economic anarchy for their development. Even if we imagine that the whole earth comes under control of a single capitalist world government, operating under a "perfect" world economic plan, and that every single economic enterprise on earth operates completely rationally within that plan, there would still be economic crises of overproduction! The reason is simple: surplus value would still be ripped off from the workers; the workers would therefore be unable to buy all that they produce; the capitalists would use up a certain part of the resulting spoils in the form of untold luxuries and extravagances, and would re-invest the rest in the expansion of the means of production; but there would come a time when the further expansion of the means of production would become obviously pointless; for awhile things might be kept going by advancing credit to the workers, but after awhile it would become apparent that the workers could never repay their loans and the credit bubble would collapse... and sooner or later stagnation and/or depression would develop. These things are inherent in capitalist commodity production, and there is no escaping them. It is not possible to have an economic plan under any form of capitalism, which will not eventually break down.

Socialism or communism without an overall economic plan is inconceivable. There is a great deal of work still necessary to understand exactly how socialist or communist economic plans should be developed and implemented. But one thing transcends all this: the realization that the law of value is fundamentally incompatible with communist planning, and that any economic plan that is based upon the continued existence of commodity production is either capitalist, or at best transitional (to the extent that the law of value is being progressively restricted). The importance of getting clear on the nature and varieties of economic anarchy which can exist under various forms of capitalism, including state capitalism, is that this helps us understand why the much-glorified economic planning in the revisionist Soviet Union is nothing more than capitalist economic planning carried as far as it can go.

Of course there is much more which could be, and should be, said about all this. I hope these introductory comments can be of some value to the discussion of the nature of the Soviet Union which is now underway.

—Scott H.

2/23/83 (edited slightly on 8/12/98)