Christian nationalism’s opponents are getting organized

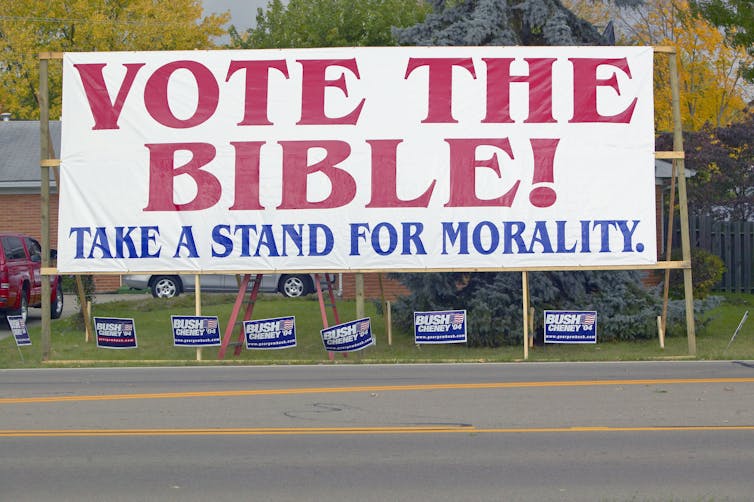

Faith groups are teaming up with liberal secular organizations to combat the ideology, which they say is a threat to democracy — and, for many, their religion.

(RNS) — On Jan. 6, 2021, Rahna Epting, the executive director of liberal advocacy group MoveOn, watched her television in horror. As supporters of then-President Donald Trump stormed the seat of U.S. democracy, Epting couldn’t help but notice the Christian symbols some waved as they surged past police barricades.

Appalled, she contacted the Rev. Liz Theoharis, a Presbyterian minister and head of the Kairos Center for Religions, Rights and Social Justice. The pair had worked together in the past and quickly brainstormed their next project: combating the forms of Christian nationalism visibly evident Jan. 6.

“There is a tribalism and a very strong, religious-like element to this MAGA movement, which we name as white Christian nationalism,” Epting said. “As a progressive, secular organizer, I don’t think me and my comrades in our space are really fully evaluating what this threat is.”

In the years since Jan. 6, however, as proponents of Christian nationalism have grown louder, so, too, have their detractors: Epting and Theoharis’ partnership turned into a yearslong project to determine how best to curb the influence of the ideology, ultimately resulting in a 75-page report titled “All of US: Organizing to Counter White Christian Nationalism and Build a Pro-Democracy Society.”

Their study is but the latest in an intensifying effort to challenge Christian nationalism and its influence on U.S. politics. Denominations are condemning the ideology. Local faith leaders are launching awareness campaigns. Clergy and secular groups are teaming up to strategize ways to combat Christian nationalism ahead of the 2024 elections.

The Rev. Liz Theoharis, from left, Rabbi Jonah Pesner, Imam Saffet Catovic and Bishop Vashti McKenzie during the Poor People’s Campaign’s congressional briefing on Sept. 22, 2022, at the Rayburn House Office Building in Washington. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Epting, Theoharis and Stosh Cotler, the former head of Bend the Arc Jewish Action and the report’s chief author, collected examples of these efforts for their study. They interviewed dozens of activists and were advised by an array of leaders with ties to religious groups such as United Church of Christ or secular organizations such as the Working Families Party. The report’s preface notes those involved include a mix of Christians and non-Christians who are united by a “shared recognition that the rise of an authoritarian strain in our politics has been fueled and emboldened by a white Christian nationalist movement.”

As they mined their findings, authors slowly came to identify ways they believe activists can blunt Christian nationalism’s impact.

“White Christian nationalists are out-organizing us in spaces we have left uncontested for far too long,” Epting said, singling out rural areas that often go underserved by local governments.

Theoharis agreed, saying advocates should be “organizing people more holistically” in order to meet “people’s material, spiritual and emotional needs, as well as political needs and aspirations.” She stressed the need for cooperation between religious and secular groups, hoping they can strategize to “build the kind of society we need,” but also signaled a desire to alter public perception of Christians.

“When people are celebrating abortion bans, they’re articulated as Christian,” she said. “But when people are feeding migrants in the desert as part of their faith practice, they’re talked about as activists.”

Many mobilization campaigns against Christian nationalism, including some mentioned in the report, draw strength from projects that predate Jan. 6. The Poor People’s Campaign, launched in 2017 by Theoharis and the Rev. William Barber II, rebooted the last campaign of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who organized the original in 1968 as a way to resist what he described as three “evils” of society — racism, poverty and war. The campaign’s recent iteration added two more to that list: ecological devastation and the “distorted moral narrative of religious nationalism,” which includes Christian nationalism.

Meanwhile, the advocacy group Faithful America has organized clergy and other faith leaders to stage protests across the country criticizing events that feature Christian nationalists — particularly the ReAwaken America Tour, a right-wing traveling roadshow typically headlined by Christian nationalist influencer and former Trump adviser Michael Flynn.

Faithful America protesters are often joined by leaders associated with groups such as Interfaith Alliance, which convened a briefing on Christian nationalism on Capitol Hill in September, or Christians Against Christian Nationalism, an effort led by Amanda Tyler of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, who recently condemned Christian nationalism in a testimony before Congress.

“Christian nationalism strikes at the heart of the foundational ideas of what religious freedom means and how it’s protected in this country, and that is with the institution of separation of church and state,” Tyler told the House Oversight Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties in December.

Tyler and others have also partnered with groups such as Americans United for Separation of Church and State and the Freedom From Religion Foundation, with the BJC and FFRF producing a joint report on the role Christian nationalism played in the Jan. 6 attack.

The idea that Christian nationalism functions as a key component of broader threats to U.S. democracy is shared among a growing number of faith leaders and activists. Pastors derided Christian nationalism while discussing voting rights at a recent Progressive National Baptist Convention gathering. Similarly, Katrina L. Rogers, media director of the faith-based advocacy group Faith in Public Life, said via email that FPL is organizing against Christian nationalism — also referred to as white Christian nationalism — because the group believes the ideology is “at the center of many of the attacks we are seeing across the country on our freedoms, including the freedom to vote and to access reproductive health care.”

According to the Rev. Jen Butler, FPL’s founder who now consults on various efforts to mobilize religious voices, the broad political impact of Christian nationalism naturally leads to team-ups between secular and faith groups.

“The religious community is pivoting directly to address white Christian nationalism, and secular funders are seeing the value that the religious community can bring to the table because of the way we have sounded the alarm on Christian nationalism — and begun to respond,” Butler told RNS this week in a phone interview.

The report, which was commissioned by the MoveOn Education Fund and the Kairos Center, proposed 11 strategies to fight the Christian nationalism. They included calling for organizations to prioritize the South, encourage Christians to mobilize their fellow faithful against Christian nationalism and “fully integrate faith communities and faith leaders into a pro-democracy movement.”

The report adds: “We agree that to effectively combat this movement, we must broaden our ranks, forge new alliances, and make changes in how we organize, both within our own communities and across them.”

Doug Pagitt takes a selfie in a crowd protesting the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, May 28, 2020. Photo by Doug Pagitt

Doug Pagitt, who is mentioned in the report and leads the liberal-leaning advocacy group Vote Common Good, said he’s attended multiple closed-door strategy sessions all over the country this year that dealt with Christian nationalism. The conversations, he said, often highlighted the influence of Christian nationalism on Republican-led efforts to restrict abortion rights or ban gender-affirming care for transgender people.

The work is growing ever more local: Pagitt said VCG has begun working with the Public School Defenders Hub, a project of the California-based Contemporary Policy Institute, to train school board candidates on Christian nationalism.

“We know that Christian nationalist groups are targeting those places,” Pagitt said, referring to school boards. “They feel that with a small amount of investment they can make a big impact.”

Indeed, a growing number of localized Christian nationalist organizations have focused their campaigns on local government entities this year, with activists sometimes delivering fiery, religion-themed speeches at public meetings. Pagitt said VCG wasn’t planning on working with school boards, but the surge in faith-fueled, right-wing activism has caught many education officials by surprise, leading the Public School Defenders Hub to seek out his group.

“Our goal here is to deepen understanding to respond more effectively in resistance,” Pagitt said.

Organized pushback against Christian nationalism is popping up in other spaces as well. Last week, around 100 faith leaders associated with Milwaukee Inner-City Congregations Allied for Hope, an interfaith coalition that goes by its acronym of MICAH, launched a new “We All Belong” campaign with the goal of protecting democracy and rejecting Christian nationalism.

And just a few days before, the Disciples of Christ denomination passed a resolution — sponsored by an array of local congregations — at its biennial General Assembly denouncing Christian nationalism as “a distortion of the Christian faith.” According to Word&Way, the gathering also featured multiple workshops focused on Christian nationalism, including a talk led by Andrew Whitehead, a sociologist at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis who has written extensively on the topic.

Whitehead, who has a forthcoming book titled “American Idolatry: How Christian Nationalism Betrays the Gospel and Threatens the Church,” told RNS he has led talks about Christian nationalism with Episcopal bishops and Seventh-day Adventists in recent months.

“There’s a growing concern across not only American Christian groups and denominations, but also those who are not necessarily partisan or even religious, responding to what they see as the threats toward democracy in the U.S., toward the Christian faith, toward interfaith collaboration,” Whitehead said.

Whether that rising concern will be enough to fully curb Christian nationalism’s influence, Whitehead wasn’t sure. But looking toward the future, he said, coalitions like the one’s forged by Epting, Theoharis and others stand a chance of winnowing the ideology’s outsized influence on American politics — and, potentially, religion.

“Over the next few decades, I think it’ll be more difficult overall for this idea of the U.S. as a Christian nation — to reflect a particular Christian expression — to be taken for granted, or to even be the privileged position across American society,” he said.

(This story was was reported with support from the Stiefel Freethought Foundation.)

Researchers found that support for Christian nationalism was strongly associated with the moral foundations of loyalty, sanctity and liberty.

Researchers found that support for Christian nationalism was strongly associated with the moral foundations of loyalty, sanctity and liberty.