Balsam Mustafa, Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow, Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Warwick

Iranian authorities have cracked down on protests which erupted after the death in custody of a 22-year-old woman who was arrested by the morality police for not wearing the hijab appropriately. The death of Mahsa Amini who was reportedly beaten after being arrested for wearing her hijab “improperly” sparked street protests.

Unrest has spread across the country as women burned their headscarves to protest laws that force women to wear the hijab. Seven people are reported to have been killed, and the government has almost completely shut down the internet.

But in the Arab world – including in Iraq, where I was brought up – the protests have attracted attention and women are gathering online to offer solidarity to Iranian women struggling under the country’s harsh theocratic regime.

The enforcement of the hijab and, by extension, guardianship over women’s bodies and minds, are not exclusive to Iran. They manifest in different forms and degrees in many countries.

In Iraq, and unlike the case of Iran, forced wearing of the hijab is unconstitutional. However, the ambiguity and contradictions of much of the constitution, particularly Article 2 about Islam being the primary source of legislation, has enabled the condition of forced hijab.

Since the 1990s, when Saddam Hussein launched his Faith Campaign in response to economic sanctions imposed by the UN security council, pressure on women to wear the hijab has become widespread. Following the US-led invasion of the country, the situation worsened under the rule of Islamist parties, many of whom have close ties to Iran.

Contrary to the claim in 2004 by US president George W. Bush that Iraqi people were “now learning the blessings of freedom”, women have been enduring the heavy hand of patriarchy perpetuated by Islamism, militarisation and tribalism, and exacerbated by the influence of Iran.

Going out without a hijab in Baghdad became a daily struggle for me after 2003. I had to put on a headscarf to protect myself wherever I entered a conservative neighbourhood, especially during the years of sectarian violence.

Flashbacks of pro-hijab posters and banners hanging around my university in central Baghdad have always haunted me. The situation has remained unchanged over two decades, with the hijab reportedly imposed on children and little girls in primary and secondary schools.

A new campaign against the enforced wearing of the hijab in Iraqi public schools has surfaced on social media. Natheer Isaa, a leading activist in the Women for Women group, which is leading the campaign, told me that hijab is cherished by many conservative or tribal members of society and that backlashes are predictable.

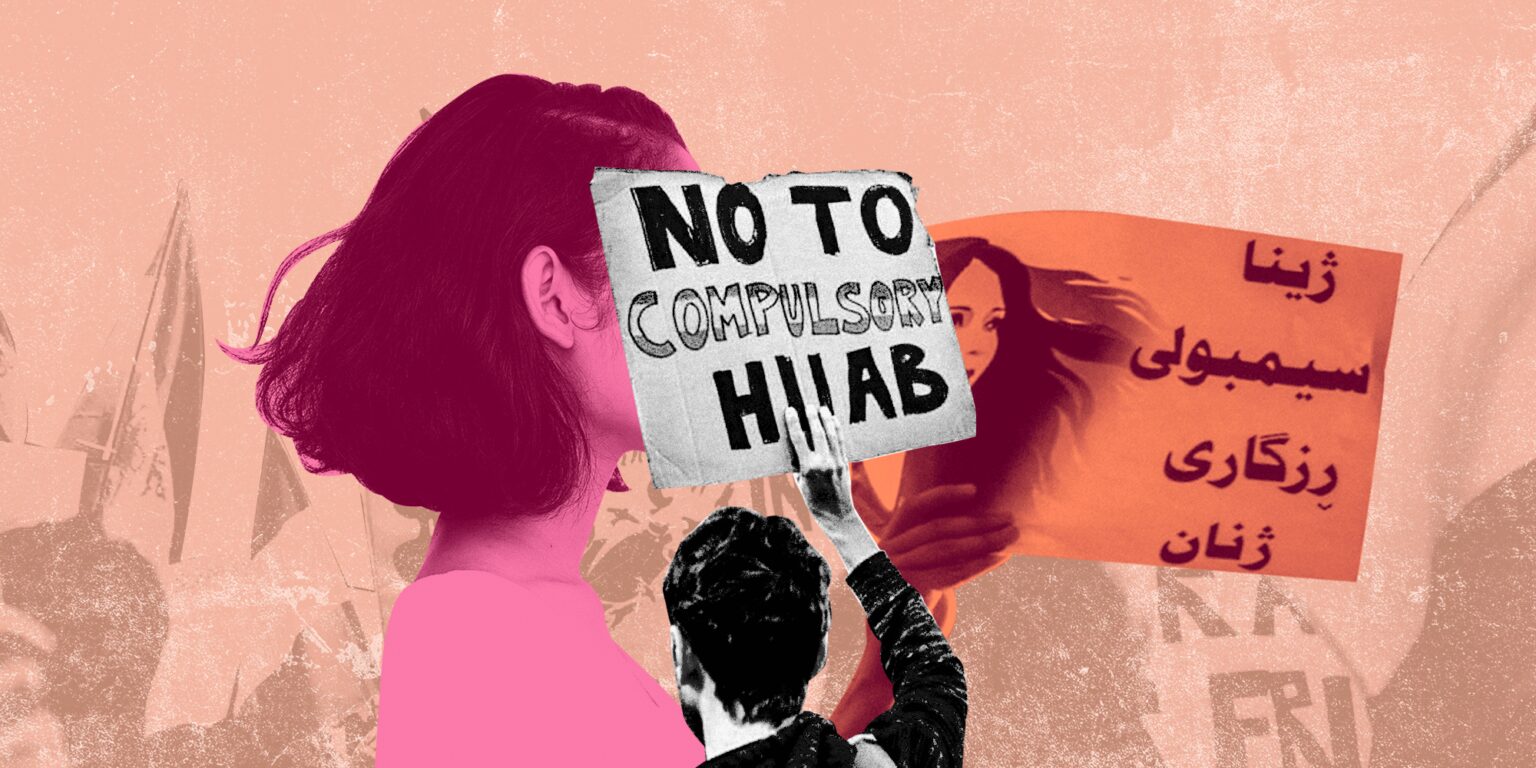

Similar campaigns were suspended due to threats and online attacks. Women posting on social media with the campaign hashtag #notocompulsoryhijab, have attracted reactionary tweets accusing them of being anti-Islam and anti-society.

Similar accusations are levelled at Iranian women who defy the regime by taking off or burning their headscarves. Iraqi Shia cleric, Ayad Jamal al-Dinn lashed out against the protests on his Twitter account, labelling the protesting Iranian women “anti-hijab whores” who are seeking to destroy Islam and culture.

Cyberfeminists and reactionary men

In my digital ethnographic work on cyberfeminism in Iraq and other countries, I have encountered numerous similar reactions to women who question the hijab or decide to remove it. Women who use their social media accounts to reject the hijab are often met with sexist attacks and threats that attempt to shame and silence them.

Those who openly speak about their decision to take off the hijab receive the harshest reaction. The hijab is linked to women’s honour and chastity, so removing it is seen as defiance.

Women’s struggle with the forced hijab and the backlash against them challenges the prevailing cultural narrative that says wearing the hijab is a free choice. While many women freely decide whether to wear it or not, others are obliged to wear it.

So academics need to revisit the discourse around the hijab and the conditions perpetuating the mandatory wearing of it. In doing so it is important to move away from the false dichotomies of culture versus religion, or the local versus the western, which obscure rather than illuminate the root causes of forced hijab.

In her academic research on gender-based violence in the context of the Middle East, feminist academic Nadje al-Ali emphasises the need to break away from these binaries and recognise the various complex power dynamics involved – both locally and internationally.

The issue of forcing women to wear the hijab in conservative societies should be at the heart of any discussion about women’s broader fight for freedom and social justice.

Iranian women’s rage against compulsory hijab wearing, despite the security crackdown, is part of a wider women’s struggle against autocratic conservative regimes and societies that deny them agency. The collective outrage in Iran and Iraq invites us to challenge the compulsory hijab and those imposing it on women or perpetuating the conditions enabling it.

As one Iraqi female activist told me: “For many of us, hijab is like the gates of a jail, and we are the invisible prisoners.” It is important for the international media and activists to bring their struggle to light, without subscribing to the narrative that Muslim women need saving by the international community.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Balsam Mustafa receives funding from The Leverhulme Trust (Grant no. ECF-2021-599).