Can The US And Iraq Move Beyond Military Ties? – Analysis

Iraq's Mohammed Al-Sudani. Photo Credit: Mehr News Agency

By James Durso

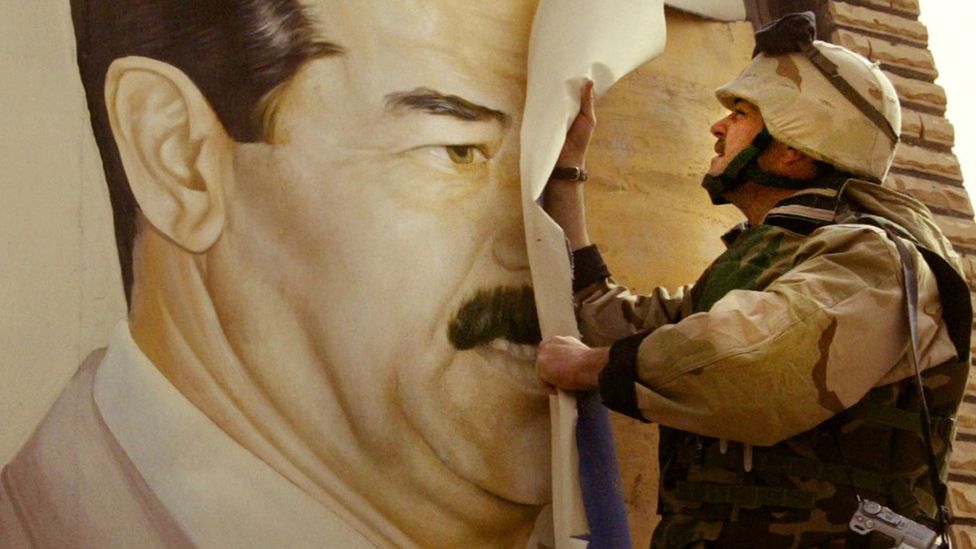

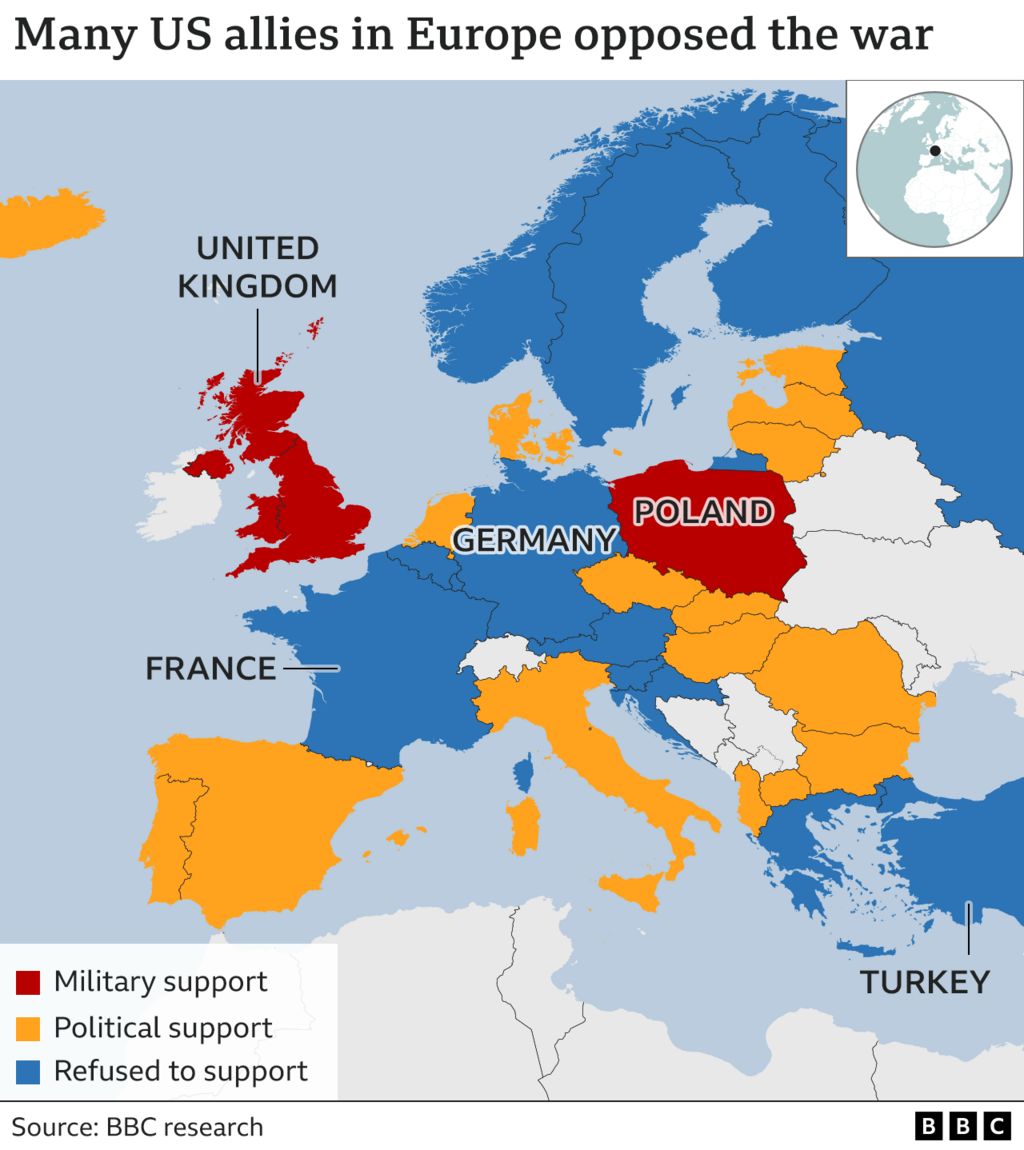

Twenty-one years ago, the U.S. and its allies invaded Iraq in the erroneous belief that the country possessed weapons of mass destruction and was allied with al-Qaida, the terror group responsible for the 9/11 attacks.

The U.S. created an occupation authority, but failed to restore order and helped spawn the insurgency that bedeviled it by dismissing the entire Iraqi military and the most experienced civil servants. Coalition troops fought a losing battle, regained their footing with the 2007 troop surge, and finally departed in 2011. U.S. troops returned in 2014 to fight the Islamic State and they remain there to this day, though ISIS was largely eliminated by 2019.

In January 2020, Iraq’s parliament voted on a nonbinding measure to remove the U.S. troops from Iraq, but the Americans remain at the request of the Iraqi government. However, in response to the parliament’s 2020 vote, Iraq and the International Coalition changed the mission of the troops from a combat mission to one of advisory and training.

Iraq’s prime minister, Mohammed Shia’ Al Sudani, will meet U.S. President Joe Biden on April 15, primarily to discuss the U.S. troop presence.

Though the U.S.-Iraq Higher Military Commission is reviewing the troop presence issue, will the U.S. side stall fearing it may have to agree to a smaller presence and constrained operations? Possibly, so Sudani may want a public commitment from Biden to force the march to a constructive, timely decision.

Aside from the troops issue, Sudani wants to strengthen Baghdad’s ties with Washington, which he considers Iraq’s top bilateral relationship, and to add an economic dimension to Iraq’s ties with America.

When Americans think of Iraq in economic terms it’s all about the oil, but in November 2023 ExxonMobil, America’s biggest oil company, exited Iraq with nothing to show for a decade-long effort. The departure will lower the expectation of other U.S. companies, but Sudani wants to revitalize economic ties, and he will be accompanied by many of the country’s top businessmen.

U.S.-Iraq trade has room for growth. In 2022, the U.S. exported $897 million in goods, the top product being automobiles. Iraq, in turn, exported $10.3 billion in goods, most of it crude oil.

A key economic objective of Iraq is the $17 billion Development Road, an overland road and rail link from the Persian Gulf to Europe via Turkey, that will host free-trade zones along its length.

Biden and Sudani should consider the shape of the future U.S.-Iraq relationship, which has to now been governed by military considerations, and has become the best example of The Meddler’s Trap, “a situation of self-entanglement, whereby a leader inadvertently creates a problem through military intervention, feels they can solve it, and values solving the new problem more because of the initial intervention. …A military intervention causes a feeling of ownership of the foreign territory, triggering the endowment effect.”

Iraq is the only real democracy in the Arab world, and many young Iraqis want a separation of religion and state, something that should resonate with Americans and, Iraqis hope, cause the U.S. to deal with Iraq as Iraq, not a platform for operations against Syria and Iran, or to support Washington’s Kurdish clients.

Washington damaged itself in Iraq by killing Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis in January 2020. Baghdad had moved the PMF, once a militia, into the government in 2016 (no doubt with American encouragement), so the killing of Muhandis, then a government official, increased popular support the PMF.

What are some clouds on the horizon for the U.S. and Iraq?

Corruption. Pervasive corruption in Iraq has slowed economic development and subjected Iraqi citizens to ineffective governance. The 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index by Transparency International ranked Iraq 154 of 180, a slight improvement from 2022 when it ranked 157 of 180.

Iraq was previously described by TI as: “Among the worst countries on corruption and governance indicators, with corruption risks exacerbated by lack of experience in the public administration, weak capacity to absorb the influx of aid money, sectarian issues and lack of political will for anti-corruption efforts.”

Sudani has not ignored corruption, calling it one of the country’s greatest challenges and “no less serious than the threat of terrorism.”

Elizabeth Tsurkov. Tsurkov is a Russian-Israeli academic who was kidnapped in 2023 by Kata’ib Hezbollah, an Iranian-influenced Iraqi militia. Tsurkov, a doctoral student at Princeton University in the U.S., entered Iraq with her Russian passport and did not disclose that she was an Israeli citizen and Israeli Defense Forces veteran. (A 2022 Iraqi law criminalized any relations with Israel.)

Tsurkov’s family wants the Biden administration to designate Iraq a state sponsor of terrorism for failing to secure her release. Sudani’s office announced an investigation into the matter and the issue may arise when Sudani meets Biden, though the best outcome for Iraq and the U.S. is a Russia-brokered deal between Israel and Iran.

If Biden designates Iraq a state sponsor of terrorism that will irreparably damage the relationship and open the door for China.

China. The U.S. is Iraq’s top relationship, but not its only relationship. China will respond to the ostracism of Baghdad by extending invitations to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS, the latter of which can fund infrastructure projects through the New Development Bank. PetroChina replaced ExxonMobil in West Qurna 1, one of Iraq’s biggest oil fields, and is ideally positioned for further expansion. And Iraq was the “leading beneficiary” of China’s Belt and Road Initiative investment in 2021.

Sudani has said Iraq should not be a cockpit of conflict for the U.S, and Iran, but when Iran is concerned it, in Washington, is always 1979. Though Sudani has many challenges to face, Biden has more: he must reorient his government away from its colonial mentality in West Asia, recognize that Baghdad must reach a modus vivendi with Tehran that may not be to Washington’s pleasure, and not smooth the way for Beijing’s greater penetration of West Asia.

This article was published at Responsible Statecraft

James Durso (@james_durso) is a regular commentator on foreign policy and national security matters. Mr. Durso served in the U.S. Navy for 20 years and has worked in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Central Asia.