Not with a bang but a whimper.

What those that deny there is a Peak Oil crisis mistakenly believe is that those who proclaim the end of the Oil Age are catastrophic hysterics. The facts which oil geolgists continue to point out is that Peak Oil is here, and its impact will change the world, not with a bang but with increasingly repetitive crisises. The Age of Oil, which has lasted for 150 years has seen the greatest environmental change caused by humans. J.R. McNeil in his book on the Environmental History of the 2oth Centruy; Something New Under the Sun, Norton, 2000, calculates that "humans in the 20th Century used TEN TIMES as much energy then our forebearers have over the last one thousand years."Something New under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth Century

by J.R. McNeill, Penguin Books Ltd., London 2000.

How will the twentieth century be remembered? For world wars and politics? The spread of literacy and sexual equality? This ground-breaking work shows us that its most enduring legacy will in fact be the physical changes we have wrought on the planet. Humanity has undertaken a gigantic experiment on the earth, refashioning it with an intensity unprecedented in history—now there really is something new under the sun. In this landmark and award-winning book John McNeil uses a refreshing mixture of history, anecdote and science, avoiding blame or sermon, to explain how and why humans have altered their world. He takes us from London smog to dust bowls of Oklahoma, introducing fascinating characters such as conservationist Rachel Carson, pirate whaler Aristotle Onassis and the little-known scientist who invented CFCs and put lead in petrol. Above all this compelling account shows that the damage can be reversed. It is up to us to decide how long our gamble can continue. WWF review

The impact of the Age of Oil can be seen in the Climate Change Crisis we face,as the two coincide. So is it any wonder that those who benefit from the current capitalist system that created the Oil Age deny that there is any crisis? They deny there is a Climate Change Crisis and they deny there is a Peak Oil crisis, and this denial is a very real threat to our continued existance.Peak Oil is coming for most producing countries, and so is global Climate Change which coincides with the oil crisis. These two crisises will create an even greater synergetic phenomena, that industrialized capitalism and finance capitalism will NOT be able to deal with.The old adage; Socialism of Barbarism, will be as relevant tommorow as it was yesterday.

Today we need to take seriously the crisis the capitalist system is in globally, while it may not appear to the average consumer in the Industrialized world it is in a crisis of global and historic proportions. It is in a period of economic, geological, and environmental decadence. Capitalism cannot deal with these two major crisis because of the anarchy of the market. No matter what proponents of sustainable or "Natural Capitalism" say. Capitalism is antiethical to human and other species survival.A planned economy under the direct control of the individuals and their communities is the historical and ONLY solution to this crisis and even then it may not be enough. Where technocracy and socialism agree is that a planned economy based on labour and energy credits not on money is the only way out of this coming calamity. And while technocracy offers a North American planning model it lacks the community council/workers councils inputs required to make this work.Only a Libertarian socialist society based on planned economy models where communities are based on self sufficieny, free associations and mutual aid, and throught the confederated sharing of excess energy, can provide the basis for really dealing with both of these pending world shaking events.

These were and are the revolutionary ideas of the 20th century and the model espoused by Kropotkin, Thorstien Vebelen, the IWW, Howard Scott, Jane Jacobs, E.F. Schumaker and Buckminister Fuller, - OPERATING MANUAL FOR SPACESHIP EARTH "You must choose between making money and making sense. The two are mutually exclusive."

R. Buckminster Fuller

Nope no catasrophic hysteria here, just the facts mam.

And the facts are Capitalism has hit its decline, its decadent period, where it may make technological breakthroughs, but these cannot be used because they are restricted to creating a profit for the sole reproduction of capital itself. This is antiethical to the creation of a human society and a sustainable environment.

This is the barbarism of capital; not merely a melt down in profits, nor a Great Depression, but an ecological disaster based on the reliance on oil which will lead to a renewed authoritarian state; fascism, as people sacrifice freedom for security.

The 20th century will stand out as a peculiar century because of the breath-taking acceleration of so many processes that bring ecological change. That idea permeates environmental historian J. R. McNeil's recent book Something New Under the Sun. McNeil points first to the change in scale in the practice of our traditional technologies in industry, transportation, and agriculture. At the end of the 20th century human activities had contributed to an increase of around 30% in the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Our level of nitrogen fixation now matches what nature herself provides. The direct transformation of land for human use now affects 39-50% of the earth's dry surface. What this will ultimately mean ecologically, we don't fully know. McNeil further argues that the 20th century has also seen a growing and radically different range of technologies of largely unknown consequence.For example:In 1930 the American Nobel Prize winner for physics said that there was no risk that humanity could do real harm to anything so gigantic as the earth. In the same year the American chemical engineer Thomas Midgley invented chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs -- which we now know can destroy the earth's protective ozone layer).The 20th century has thus seen the modern landscape become an uncontrolled experiment of grand scale.McNeil concludes: What Machiavelli said of affairs of state is doubly true of affairs of global ecology and society. It is nearly impossible to see what is happening until it is inconveniently late to do much about it. Introductory Remarks: Natural Resource Stewardship Mike Soukup, Associate Director, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science

When will we reach Peak Oil?

2008? 2010? 2020?

Coming oil crisis feared John VidalGuardian Weekly April 29 2005One of the world's leading energy analysts called this week for an independent assessment of global oil reserves because he believes that Middle Eastern countries may have far less than officially stated and that oil prices could double to more than $100 a barrel within three years, triggering economic collapse. Matthew Simmons, an adviser to President George Bush and chairman of the Wall Street energy investment company Simmons, said that "peak oil" -- when global oil production rises to its highest point before declining irreversibly -- was rapidly approaching even as demand was increasing. "This is a new era," Mr Simmons told a conference of oil industry analysts, government officials and academics in Edinburgh. "There is a big chance that Saudi Arabia actually peaked production in 1981. We have no reliable data. Our data collection system for oil is rubbish. I suspect that if we had, we would find that we are over-producing in most of our major fields and that we should be throttling back. We may have passed that point." Mr Simmons told the meeting that it was inevitable that the price of oil would soar above $100 as supplies failed to meet demand. "Demand is pulling away from supply . . . and we have to ask whether we have the resources that we think we do. It could be catastrophic if we do not anticipate when peak oil comes." The precise arrival of peak oil is hotly debated by academics and geologists, but analysts increasingly say that official US Geological Survey estimates that it will not happen for 35 years are over-optimistic. According to the International Energy Agency, which collates data from all oil-producing countries, peak oil will arrive "sometime between 2013 and 2037", with production thereafter expected to decline by about 3% a year.

The end of oil is closer than you thinkOil production could peak next year, reports John Vidal. Just kiss your lifestyle goodbye

John VidalThursday April 21, 2005The GuardianThe one thing that international bankers don't want to hear is that the second Great Depression may be round the corner. But last week, a group of ultra-conservative Swiss financiers asked a retired English petroleum geologist living in Ireland to tell them about the beginning of the end of the oil age.

They called Colin Campbell, who helped to found the London-based Oil Depletion Analysis Centre because he is an industry man through and through, has no financial agenda and has spent most of a lifetime on the front line of oil exploration on three continents. He was chief geologist for Amoco, a vice-president of Fina, and has worked for BP, Texaco, Shell, ChevronTexaco and Exxon in a dozen different countries.

"Don't worry about oil running out; it won't for very many years," the Oxford PhD told the bankers in a message that he will repeat to businessmen, academics and investment analysts at a conference in Edinburgh next week. "The issue is the long downward slope that opens on the other side of peak production. Oil and gas dominate our lives, and their decline will change the world in radical and unpredictable ways," he says.

Campbell reckons global peak production of conventional oil - the kind associated with gushing oil wells - is approaching fast, perhaps even next year. His calculations are based on historical and present production data, published reserves and discoveries of companies and governments, estimates of reserves lodged with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, speeches by oil chiefs and a deep knowledge of how the industry works.

"About 944bn barrels of oil has so far been extracted, some 764bn remains extractable in known fields, or reserves, and a further 142bn of reserves are classed as 'yet-to-find', meaning what oil is expected to be discovered. If this is so, then the overall oil peak arrives next year," he says.

If he is correct, then global oil production can be expected to decline steadily at about 2-3% a year, the cost of everything from travel, heating, agriculture, trade, and anything made of plastic rises. And the scramble to control oil resources intensifies. As one US analyst said this week: "Just kiss your lifestyle goodbye."

"The first half of the oil age now closes," says Campbell. "It lasted 150 years and saw the rapid expansion of industry, transport, trade, agriculture and financial capital, allowing the population to expand six-fold. The second half now dawns, and will be marked by the decline of oil and all that depends on it, including financial capital."

So did the Swiss bankers comprehend the seriousness of the situation when he talked to them? "There is no company on the stock exchange that doesn't make a tacit assumption about the availability of energy," says Campbell. "It is almost impossible for bankers to accept it. It is so out of their mindset."

The Long EmergencyWhat's going to happen as we start running out of cheap gas to guzzle?

By JAMES HOWARD KUNSTLERRolling Stone Magazine FeatureThe term "global oil-production peak" means that a turning point will come when the world produces the most oil it will ever produce in a given year and, after that, yearly production will inexorably decline. It is usually represented graphically in a bell curve. The peak is the top of the curve, the halfway point of the world's all-time total endowment, meaning half the world's oil will be left. That seems like a lot of oil, and it is, but there's a big catch: It's the half that is much more difficult to extract, far more costly to get, of much poorer quality and located mostly in places where the people hate us. A substantial amount of it will never be extracted.

The United States passed its own oil peak -- about 11 million barrels a day -- in 1970, and since then production has dropped steadily. In 2004 it ran just above 5 million barrels a day (we get a tad more from natural-gas condensates). Yet we consume roughly 20 million barrels a day now. That means we have to import about two-thirds of our oil, and the ratio will continue to worsen.

The U.S. peak in 1970 brought on a portentous change in geoeconomic power. Within a few years, foreign producers, chiefly OPEC, were setting the price of oil, and this in turn led to the oil crises of the 1970s. In response, frantic development of non-OPEC oil, especially the North Sea fields of England and Norway, essentially saved the West's ass for about two decades. Since 1999, these fields have entered depletion. Meanwhile, worldwide discovery of new oil has steadily declined to insignificant levels in 2003 and 2004.

Some "cornucopians" claim that the Earth has something like a creamy nougat center of "abiotic" oil that will naturally replenish the great oil fields of the world. The facts speak differently. There has been no replacement whatsoever of oil already extracted from the fields of America or any other place.

Now we are faced with the global oil-production peak. The best estimates of when this will actually happen have been somewhere between now and 2010. In 2004, however, after demand from burgeoning China and India shot up, and revelations that Shell Oil wildly misstated its reserves, and Saudi Arabia proved incapable of goosing up its production despite promises to do so, the most knowledgeable experts revised their predictions and now concur that 2005 is apt to be the year of all-time global peak production.

It will change everything about how we live.

The End of Cheap Oil

Implications of Global Peak Oil

by Mark Anielski

In a technical paper to the US Association of Petroleum Geologists in 1956, a senior scientist at Shell Oil Company, Dr. M. King Hubbert, made a controversial prediction that US oil production would peak in the early 1970s. Shell encouraged him to quietly bury this paper, but Hubbert refused.

According to Hubbert, the US would eventually face a critical tipping point in energy security: Peak Oil — the point in time when extraction of oil from the earth reaches its highest point and then begins to decline. ‘Hubbert’s peak theory’ predicted that, with Peak Oil, prices would fluctuate wildly, resulting in economic seismic shocks, even as demand for oil and gas continued to rise. He did not say that the US was going to run out of oil, per se, but that a peak in domestic production would result in economic tremors felt around the world.

The consequences of global Peak Oil would indeed be catastrophic. It would herald the end of cheap oil at a time when global demand for oil is growing, driven by the voracious energy appetite of China and other developing countries. Unfortunately, most people, especially our politicians, seem oblivious to this looming crisis or are extremely reluctant to talk about it.

All signs seem to suggest that this issue will soon demand a greater degree of public attention. A group of oil analysts led by petroleum geologist Colin Campbell — the Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas (ASPO) — has predicted that global oil production will peak in 2005. Important oil producers like UK and Norway have already experienced Peak Oil - in 1999 and 2001 respectively. Saudi Arabia’s production is expected to peak in 2008 followed by Kuwait in 2015 and Iraq in 2017. Canada’s own Peak Oil event occurred in 1973, and our natural gas production peaked in 2001,without much notice.

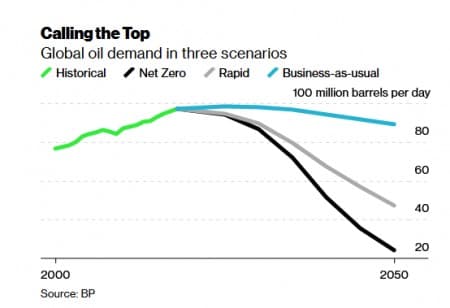

Of course, because there will always be disagreement among geologists on petroleum statistics, no one knows precisely when global oil and gas production will peak. Even if you are a technological optimist, there is no getting around the basic problem of rising demand and lagging production capacity. Based on the figures I have researched, global oil production in 2001, at 76 million barrels per day (bbd), outstripped global production of 74 million bbd in 2004. And in 2004, global oil consumption reached 80 million bbd, growing by 2.2 million bbd over 2003 levels, the highest growth in demand since 1978. Of this amount, the US alone consumed 25% of the world’s total oil production

Oil industry executives are also worried. Harry L. Longwell, executive Vice-President of Exxon-Mobil warned: “The catch is that while [global] demand increases, existing production declines… we expect that by 2010 about half the daily volume needed to meet projected demand is not on production today.” In a speech in the autumn of 1999, Vice-President Dick Cheney warned that, "By 2010, we will need on the order of an additional fifty million barrels a day. Exxon-Mobil will have to secure over a billion and a half barrels of new oil equivalent reserves every year just to replace existing production.” Putting this in the context of Alberta, oilsands production is predicted to reach a maximum of 1.56 million bbd by 2012, which is only 3% of the additional global daily demand predicted by Cheney.

According to Colin Campbell, the world is running at full production capacity. With global Peak Oil looming, he predicts that global oil and gas prices will fluctuate wildly, fall back once or twice and then reach sustained price highs.

What about Alberta? Why should we care, living in debt-free and oil-rich province? First, few people noticed that Alberta’s peak in conventional crude oil occurred in 1973 and natural gas production peaked in 2001. Fortunately, in the oilsands, Alberta has arguably the world’s largest reserves of non-conventional oil, with an estimated 300 billion barrels of proven reserves (although official international statistics report 174 billion barrels). This means that Alberta’s official reserves exceed Saudi Arabia’s.

While Alberta’s impressive reserves would last 500 years at a predicted maximum production of 2.0 million bbd (a volume quadruple today’s production), they would only supply the entire projected world 2012 oil consumption demands (95 million bbd) for less than 9 years or supply 10% of current US consumption of 20 million bbd.

The problem for Alberta is not only the limited reserves of oilsands, but the growing scarcity of natural gas needed to power its extraction. Most importantly, Alberta’s natural gas production peaked in 2001, without anyone noticing. Oilsands production is highly energy intensive and relies mostly on natural gas. It takes the energy of about one barrel of oil (from natural gas) to produce 4 barrels of synthetic crude oil. At current production volumes and remaining gas reserves, Canada has less than 10 years of natural production remaining.

Another serious problem for Alberta is water. Oilsands production requires huge amounts of water: each barrel of oil produced from oilsands requires about six barrels of water. For each barrel of oil produced, about one barrel of water is permanently lost from the hydrological cycle. Alberta’s oilsands producers are currently licensed to use 26% of the province’s groundwater, in addition to surface water from rivers and lakes.

Combining the impacts of dwindling natural gas supplies in the face of growing domestic and US demand and growing demand for surface and groundwater supplies, Alberta’s oil paradise may not be as rosy as it first appears.

- But what about the consequences of global peak oil in 2005 for Alberta? I predict the following:

- Dramatic oil and natural price shocks resulting in budgeting challenges for Alberta;

- Greater pressure by US (in competitive conflict with China) to secure even more oil from the oilsands and natural gas;

- Growing demand from China for Alberta’s oil and gas, including Canadian resource companies;

- US and industry pressure to maintain an already favorable royalty regime for oilsands; and

- Greater global conflict for each remaining barrel of oil, especially in areas such as the Middle East.

In spite of this gloomy global peak oil scenario there is an opportunity for Alberta to take a leadership role by investing today in greater energy efficiency and conservation, and by promoting the transition to a renewable energy future in our homes, businesses and communities. At stake is nothing less than the economic well-being of the world.

In a post-debt, we have a responsibility to the children of Alberta and the world to show leadership by investing prudently in the frugal use of our resources and gushing resource revenues.

Author: Mark Anielski is a well-being economist and Adjunct Professor of Corporate Social Responsibility and Social Entrepreneurship at the School of Business, University of Alberta and Adjunct Professor of Sustainability Economics at the Bainbridge Graduate Institute in Washington. Part of this paper is from his presentation to the Council of Canadians on Energy and Canada-US Relations on November 30, 2004 at the University of Calgary.