As summer approaches, the French government and its media echo chambers are once again launching an Islamophobic offensive. By seizing on a newly released report about the so-called ‘influence’ of the Muslim Brotherhood, they are using a crude pretext to target and suppress any visible expression of Islam in society. This comes in the wake of the brutal murder of 22-year-old Aboubakar Cissé, a Malian-born carpenter who was stabbed 57 times while praying in a mosque — a horrific hate crime. We are republishing this article from last summer as a stark testament to the deep-rooted, cartoonish racism and bigotry that pervade the so-called “Cradle of Human Rights.” Although originally written for the French CGT Education teachers’ union, the article’s author has since been expelled for criticizing the Confederation’s stance on Gaza (see this petition).

The summer period is notoriously prone to forest fires, a formidable threat to our natural resources and the surrounding biodiversity. However, there is an even more insidious danger spreading through our societies, undermining our values and cohesion: irresponsible hate speech. A reminder of some recent occurrences is in order.

Occitan Hearth

At the end of April, in elementary schools, middle schools, and high schools in the Academies of Toulouse and Montpellier [French southern cities of the Occitania region], a survey on “absenteeism” during the month of Ramadan and the Eid al-Fitr holiday, particularly affecting priority education zones [underprivileged areas with a significant Muslim community], targeted exclusively Muslim pupils. Commissioned by the Interior Ministry, this survey was required from schools by the police and the Ministry of Education. This situation provoked a legitimate outcry.

Following the denunciation of these stigmatizing practices — which turn a basic practice of Islam into a security issue — fraught with illegality, since religious statistics (even non-nominative ones) are strictly regulated in France, the authorities, as usual, talked a lot of hot air: “clumsiness”, “badly formulated message”, “autonomous research by an intelligence officer”, “study of the impact of certain religious holidays on the operation of public services”… As if cops were known for carrying out sociological investigations in schools; as if a religion other than Islam had ever been in the line of fire; as if occasional absences, provided for in the Education Code and legally unassailable (for the time being), could harm the functioning of Europe’s most overcrowded classrooms — after Romania.

A wet-finger estimate in [the right-wing newspaper] Le Figaro, announcing a “record absenteeism rate” on the day of Eid al-Fitr 2023 due to an alleged “TikTok trend,” is said to have prompted this investigation, which is perhaps intended to provide more quantified data for future witch-hunts. The data, moreover, is hardly usable, for while some school heads and inspectors have encouraged staff to respond to these tendentious surveys, which we can only deplore and denounce, others have fortunately dissuaded them from doing so — not to mention the fact that it is difficult to presume the reason for an absence on a Friday just before the national school holidays.

The question immediately arose as to the motives behind such a survey. Was it “only” a question of stirring up yet another unfounded controversy at the expense of the Muslim community? Or is the government planning to call into question an acquired right that is in no way contentious, in the name of an ever more narrow and misguided interpretation of secularism (which could tomorrow attack pork-free or meat-free menus in school canteens, ban any refunding of half-boarding fees for Muslim pupils during the month of Ramadan, etc.)? Will staff be the next targets of these investigations? Already, some non-teaching staff have been refused a “religious holiday” leave, which is illegal and unacceptable. Any attempt to generalize these measures on the pretext of “combating separatism” and “ensuring the smooth running of the public education service” must be fiercely opposed.

PACA Hearth and Ministerial Fuel to the Fire

On June 15, the Mayor of Nice and President of the Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur (PACA) Regional Council, Christian Estrosi, issued an alarmist press release denouncing “several extremely serious incidents” which had occurred the previous day in three Nice elementary schools, and which were reported to the School Inspection Office, then to the Prefect of the Alpes-Maritimes Department, and the Prime Minister, Elisabeth Borne. The following day, the French Minister of Education, Pap Ndiaye, went even further, speaking of “intolerable facts,” the “mobilization of the Values of the Republic teams in all the schools concerned to ensure full respect for the principle of secularism on a permanent basis,” and the implementation of “the necessary government measures” to ensure respect for secularism — or “laïcité” — in schools.

The alleged “facts”? Some children in 4th and 5th grades were said to have “performed the Muslim prayer in their school playground” or organized “a minute’s silence in memory of the Prophet Mahomet[1].” These were nothing more than rumors, as the expressions of doubt (“it is reported to me,” “or”) and the conditional tense (“These unacceptable situations would also have taken place in secondary schools”) clearly underlines. Worse still, before even the slightest verification of these absolutely insignificant alleged facts (it’s just a handful of 9–10 year olds having fun in the playground), Christian Estrosi likened these “attempts at religious intrusion into the sanctuaries of the Republic that are our schools” to “religious obscurantism attempting to destabilize us” and to “families who left to wage jihad in Syria,” who are reportedly beginning to return to France and sending their children “to our schools.”

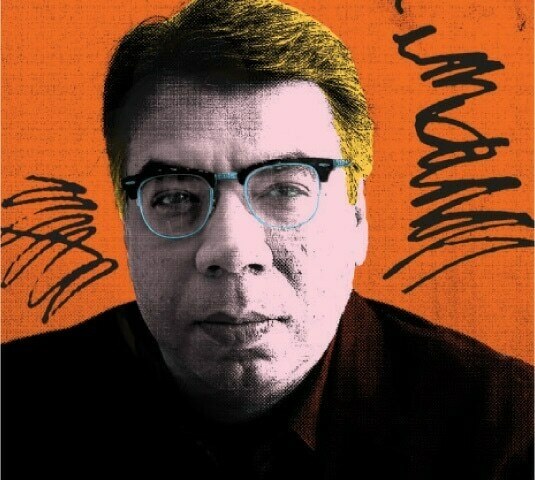

Pap Ndiaye and Christian Estrosi

And without even waiting for the results of “the General Inspectorate’s investigation to establish the facts precisely and draw the appropriate conclusions” (no kidding), the full force of the law was brought to bear against this allegedly dangerous “slide” (which at this stage has not even gone beyond the stage of gossip): “meeting with all the departments concerned to set up an action plan,” “reinforcement of State action to ensure that these attacks on secularism are firmly combated,” “campaign to prevent and combat radicalization,” “firm, collective, and resolute response,” setting up “secularism and values of the Republic training courses” which “will be the subject of a common module bringing together all personnel…” The joint press release from Christian Estrosi and Pap Ndiaye concluded with a fanfare worthy of this outpouring of catastrophist press releases, disproportionate means, and withering epithets: “the principle of secularism is non-negotiable in our Republic.” Such a display of paranoia and hysteria is not surprising from the reactionary clown Estrosi, whose secular fervor is otherwise well known, but considering what Pap Ndiaye was before he plunged body and soul into the political cesspool (Pap Ndiaye was a Professor at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, focusing his research on the compared history of racially discriminatory practices in France and in America, and the Director of the French national museum of immigration], one can only feel a bitter mixture of disgust and pity)[2].

Christian Estrosi’s uncompromising crusade for secularism: “Defending our Christian traditions also means defending the heritage of our elders, who also built our Nice countryside”.

An Eternal Flame

The deep-seated motivations behind such Islamophobic outbursts are well known and have unfortunately become a constant in the discourse of Emmanuel Macron and his minions. Having faced massive popular opposition with the pension reform, they now resort to a despicable strategy of scapegoating, reminiscent of the darkest hours of France’s history. In a notorious debate with Marine Le Pen, President of the Far-Right Party “Rassemblement National” (National Rally), Macron’s Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin accused her of being “too soft” on Islam and refusing to “name the enemy”: “You say that Islam isn’t even a problem… You need to take vitamins, you’re not harsh enough!”

During a special evening dedicated to Samuel Paty [French teacher who was beheaded by a radicalized Islamist for showing his pupils derogatory Charlie Hebdo cartoons depicting the Prophet of Islam], Darmanin also denounced “communitarianism” and the “baser instincts” of “separatism” related to clothing or food (again, no kidding). He criticized clothing stores offering “community outfits” and the “halal sections” of supermarkets, portraying these as shocking practices. His aim was to link these cultural practices, which are perfectly harmless and consensual, to terrorism — a despicable process of amalgamation, stigmatization, and the appropriation of far-right discourse that is increasingly overt in the discourse and practices of Macron and his ministers.

Far from deterring the Rassemblement National’s electorate, this trivialization has only served to consolidate and grow it, providing a vigorous “vitamin” treatment regularly administered to hate speech by those in power and their media echo chambers.

The infamous Charlie Hebdo contributed on this ominous issue with a cartoon (“School reinvents itself” — “We bring our homework to school”) and a comment: “The question is how to deal with these cases, which involve particularly young children. The ten-year-old boy who incited his classmates to observe a minute’s silence for the Prophet was the subject of ‘worrying information’ sent to the Alpes-Maritimes departmental council, as the Nice education authority told Charlie Hebdo. An alert was also issued to the prefecture for ‘suspicion of radicalization’. ‘The child doesn’t become flagged as a serious threat to national security,’ we’re told. The idea is for the intelligence services to rule out any threat and check that the parents are not dangerous.’ In the meantime, the schoolboy has been excluded from the school canteen and has taken an early vacation. ‘We can’t afford another Samuel Paty,’ says a member of the Rector’s entourage.” In any case, it wouldn’t be the first time that alleged TikTok “cyber-attacks on secularism” or other unverified gossip causes an uproar in the services of the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of National Education. Let us mention the controversies surrounding the wearing of the abaya and the deployment of the Orwellian concept of “improvised religious clothing,” promoted during the dubious “laïcité” training courses imposed on all teaching staff throughout France. These courses provide instructions and even rhetorical and legal tools to track down alleged intentions behind the “suspicious” dresses of presumably Muslim girls. A dress bought at H&M could thus fall under the “law banning ostentatious religious signs” (which really only targeted the Islamic veil) and earn the targeted schoolgirls summons, reprimands, or even threats and exclusion if they refuse to dress in a “republican” manner: a “morality police” doubled with a “thought police” in short. And it seems that the French authorities have just introduced a “children’s games police [3].” Are we soon to see SWAT teams in primary school playgrounds? The degree of insanity is such that a sneeze from a swarthy pupil that sounds vaguely like “Allahu Akbar” would be enough to trigger such an intervention.

Extinguishing the fires or fanning them?

At a time when violence, including far-right terrorism targeting our fellow Muslim citizens, is reaching worrying proportions, the government persists in fanning the flames of hatred with its pyromaniac actions, exacerbating the real dangers threatening civil peace. The government’s approach involves all-out repression, police and security abuses with total impunity [the French police are lately becoming seditious and openly rebellious, literally demanding a license to beat up and even kill without being bothered by any kind of justice procedure], and over-instrumentalizing trivial facts to raise the specter of fantasized threats. These tactics only serve to pit citizens against each other and divide the French society.

The republican school urgently needs resources, not diversionary strategies, artificial tensions, or a perpetual call into question of the status and fundamental rights of users and staff. The “non-negotiable” secularism promoted and ardently defended by the CGT Educ’action aims to ensure the serenity and cohesion of the educational community, not to transform staff into zealous police auxiliaries or confine an entire population to the status of suspect or “enemy within,” to be constantly monitored and held at bay.

The Republic guarantees freedom of worship and equal treatment for all its citizens. Anyone committed to republican ideals must protest against this frenzied desire to ignite bonfires from the most microscopic twigs, and against stigmatizing and discriminatory practices that tarnish France’s image abroad and regularly elicit condemnations from human rights associations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. National Education staff, in particular, must oppose these practices and report them to local union sections, which must vigorously defend all members of the educational community (staff, pupils, parents…) who fall victim to them.

ENDNOTES:

[1] The minute’s silence isn’t precisely a well-known practice in Muslim liturgy. As for the spelling “Mahomet,” we can only deplore the fact that despite the presence of the first name Mohammed in the top 10 of most given names in the current French population, and its position in the top 50 of names on French war memorials from the First World War, this backward-looking and contemptuous name dating from an era of antagonism between Christianity and Islam, and felt as an insult by millions of Muslims, remains in use.

[2] Like a downsized version of Voltaire fighting fanaticism in the days of the Inquisition, Pap Ndiaye has also taken to TV to denounce these “manifestations of religious proselytism in schools,” gargling in big words, notably BFM WC (“These facts are not acceptable in the School of the Republic… It is only natural that the Nice Academy, the Nice Rector, and the Nice Mayor should react firmly to ensure respect for the principles of secularism, which is why I have signed this joint declaration with the Nice Mayor… The parents have been summoned… The pupils have been reminded of their obligations with regard to religious neutrality, and they have been given training, because we’re talking about children after all… In secondary schools, [for similar acts] there can be sanctions [or even] temporary or permanent exclusions…”). Pap Ndiaye did not hesitate to spread false Islamophobic information, namely that these children all belonged to the Muslim faith, which was denied by Eliane’s testimony to BFM Côte d’Azur, whose non-Muslim grandson took part in these children’s games: “He should check his sources because my grandson was part of the group playing and imitating prayer. There was no intention, no religion in the middle, it was really just a game… The stigmatization of children is really lamentable… That’s why we no longer have confidence in politicians, because everything is blown out of proportion to unbelievable proportions, and this harms solidarity and life together.”

[3] Let us remind that to be valid, Muslim prayer (especially in congregations) requires the age of puberty, a precise timetable, ablutions, specific clothing, orientation towards Mecca, etc.; so many conditions that it is simply impossible to meet in an elementary school playground during the lunch break.