It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Friday, February 14, 2020

the imagination in the wake of Surrealism

Corneli van den Berg

Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements in respect of the Masters’ degree

qualification in the Department of Art History and Image Studies in the Faculty

of Humanities at the University of the Free State

Supervisor: Prof E.S. Human

Co‐supervisor: Prof A. du Preez

Date: October 2015

TABLE OF CONTENTS I

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS II

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS III

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCING THE IMAGINATION IN THE WAKE OF SURREALISM 1

1.1 DIEGO RIVERA’S LAS TENTACIONES DE SAN ANTONIO 5

1.1.1 Surrealist ‘poetic images’ 8

1.1.2 Shared imagining 10

1.1.3 Hypericonic dynamics 12

1.2 METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS 17

1.2.1 Image‐picture distinction 17

1.2.2 Archival approach 19

1.2.3 Chapter overview 20

CHAPTER 2: THE DANGEROUS POWER OF IMAGES – TORMENTING AND SEDUCTIVE IMAGERY IN THE

TEMPTATION OF ST ANTHONY 23

2.1 THE LEGEND OF ST ANTHONY: A TOPOS OF THE IMAGINATION 24

2.2 THE CHRISTIAN SAINT IN PATRISTIC LITERATURE 26

2.3 ST ANTHONY IN EARLY MODERN DEPICTIONS 27

2.4 THE SAINT AS MODERN ARTIST 32

2.5 FLAUBERTIAN ST ANTHONY AND HIS SEDUCTIONS 33

2.6 ST ANTHONY AS A SURREALIST TOPOS 36

CHAPTER 3: THE SURREALIST IMAGINATION 45

3.1 PRODUCTIVE IMAGINING 46

3.2 PERTINENT MOMENTS IN THE PHILOSOPHICAL HISTORY OF THE IMAGINATION 48

3.3 VISIONARY IMAGINING 52

3.4 SURREALIST IMAGING ACTIONS: AUTOMATISM, CHANCE, DREAM & PLAY 54

3.5 ALCHEMY: A SURREALIST METAPHOR 61

3.6 APPROPRIATING SO‐CALLED PRIMITIVISM 64

CHAPTER 4: ON THE EDGE OF SURREALISM: A LATIN AMERICAN CLUSTER OF WOMEN ARTISTS 72

4.1 WOMEN AND SURREALISM 74

4.2 FRIDA KAHLO: AN UNWILLING SURREALIST 77

4.3 REMEDIOS VARO: COSMIC WONDER 82

4.4 LEONORA CARRINGTON: ALCHEMICAL SURREALISM 85

CHAPTER 5: IN THE WAKE OF SURREALISM: SURREALISM IN SOUTH AFRICA 92

5.1 ALEXIS PRELLER: DISCOVERING ARCHAIC AFRICA 95

5.2 CYRIL COETZEE: ALCHEMICAL HISTORY PAINTING 99

5.3 BREYTEN BREYTENBACH: A SURREALIST PAINTER‐POET 103

CHAPTER 6: CONCLUSION 112

BIBLIOGRAPHY 118

APPENDIX A 132

SUMMARY

Summary

This thesis reports an exploration of various interrelated facets of human imaging and

imagining using the literary and artistic movement, French Surrealism, as catalyst. The ‘wake of Surrealism’ – a vigil held at the movement’s passing, as well as its aftereffects – indicates my primary focus on ideas concerning the imagination held by members of the Surrealist movement, which I trace further in selected artworks of a cluster of women surrealists active in Latin‐America as well as select artists in the South African context.

The Surrealists desired a return to the sources of the poetic imagination, believing that the

so‐called ‘unfettered imagination’ of Surrealism has the capacity to create unknown worlds,

or the potential to envision often startling and strange realities. Not only did members of

Surrealism have a high regard for the imagination, they also emphasised particular

involuntary actions and unconscious functions of the imagination, as evidenced in their use

of the method of automatic writing, dreams, play, objective chance, alchemy and so‐called

primitivism.

In this investigation I follow digital‐archival procedures rather than being in the physical

presence of the artworks selected for interpretation. Responding to this limitation and to

the current interest in image theory, I elaborate a method of art historical interrogation,

based on the eventful and affective power of images. This exploration of the imagination

into Surrealism’s wake therefore also functions as a ‘pilot study’, to determine the viability

of this approach to image hermeneutics. I appropriate and expand W.J.T. Mitchell’s notion

of ‘hypericons’ to develop the proposed concept of ‘hypericonic dynamics’. The hypericonic

dynamic transpires in ‘hypericonic events’, through the cooperative imaging and imagining

eventfulness of the interaction between artist and spectator, mediated by artworks. The

dynamic is especially prominent in artworks with a metapictorial tenor.

With hypericonic dynamics and metapictorial thematics as my heuristic method, I

investigate artworks by three women surrealists – Frida Kahlo, Remedios Varo, and Leonora Carrington – living and working in Latin‐America after the Second World War, and after the French Surrealist movement had already experienced its decline. Against the backdrop of indigenous visual culture their distinct individual styles are also related to Magical realism in the Latin‐American literary context, a style which overlaps and intersects with Surrealism. I expand upon insights gained in investigating the women in Mexico, to determine whether select South African artists, Alexis Preller, Cyril Coetzee, and Breyten Breytenbach belong in the wake of Surrealism.

The central aim of my exploration of the imagination is to gain a deeper understanding of

the everyday human imagination and its myriad operations in daily life, for the greater part

conducted below the threshold of consciousness. The imagination is a universal human

function, shared by all, yet also operational at an individual level. It also performs a unique

function of image creation in the specialised domain of the fine arts. I understand the

imagination to be irreducible, while often working in a subconscious, involuntary, and

supportive, but nevertheless primary manner in everyday human life.

Keywords:

Surrealism, imagination, image studies, Bildwissenschaft, metapictures, hypericons, ‘power

of images’, ‘hypericonic dynamics’, St Anthony, women surrealists.

INTRODUCTION

In this thesis I aim to explore various interrelated facets of human imaging and imagining using the literary and artistic movement, French Surrealism, as a catalyst for this investigation. I propose Surrealism, with its emphasis on highly imaginative and challenging artistic creations, can be a valuable springboard for studying human imaging and imagining capabilities and activities, both artistic and non‐artistic. For a period of approximately two decades, Surrealism was one of the dominant movements of the modernist avant‐garde in Europe.1 Although situated, diachronically, within the modernist avant‐garde, the Surrealist movement followed its own historical trajectory. In contrast to what one could term Greenbergian ‘mainstream modernism’, and its predominantly formalist rush toward aesthetic autonomy in the various forms of non‐ figurative expressionism, constructivism, and minimalism, and the search for aesthetic purity, Surrealism was interested in researching the roots of the imagination, in the subconscious and dreaming.2 The surrealist period style or time‐current took form and solidified into the French Surrealist movement with the publication of André Breton’s First Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924.3 Various authors, including Theodor Adorno in his 1956 essay Looking back on Surrealism, remark on the fact that French Surrealism did not survive the Second World War. Reasons given for this termination include the fact that most of the group’s members no longer resided in Paris, having become exiles in America during the war, and since the changes in bourgeois society that they had called for, after the destruction of the Great War, no longer applied (Adorno 1992: 87).4 Therefore, the French movement can be described as having a reasonably well‐defined beginning and ending.

1 Cf. Poggioli (1968), Calinescu (1977), Bürger (1984).

2 Abstraction, grounded in the early twentieth century work of Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky, was, according to Cheetham (1991: xi) the most daring and challenging development to occur in Western painting since the Renaissance. Abstraction, or the search for the aesthetic ideology of purity, had crucial consequences for all aspects relating to art – for art ‘itself’, its creation and embodiment, as a model for society, and – closely related – for art as a political force (Cheetham 1991: 104).

3 When I am referring to the core French group the terms ‘Surrealism’ or ‘Surrealist’ will be spelled with a capital ‘S’. I indicate the broader ‘surrealist’ dynamic or time‐current, and the wake of ‘surrealism’, by using a lowercase ‘s’.

4 Adorno and other members of the Frankfurt School were also exiled in America, until eventually becoming disenchanted with the so‐called progressive free West, and returning to Germany. 2 still be alive and endure (Breton 2010: 35, 129).

5 Maurice Nadeau, Surrealism’s premier historian, allows that the movement might have failed in achieving the societal revolution it had called for, but denies that it is dead, believing the surrealist attitude or mind‐set to be “eternal” (Nadeau 1965: 35).

Tuesday, October 15, 2024

Surrealist Manifesto

2024 marks the 100th anniversary of the formal announcement of surrealism in the Surrealist Manifesto written by French poet, André Breton. It gathers strength today as it combines with anarchism to shout: ALL POWER TO THE IMAGINATION!by David Tighe

Fifth Estate # 415, Summer 2024

a review of

Surrealism and the Anarchist Imagination by Ron Sakolsky. Eberhardt Press, 2023

“Contrary to prevalent misdefinitions, surrealism is not an aesthetic doctrine, nor a philosophical system, nor a mere literary or artistic school. It is an unrelenting revolt against a civilization that reduces all human aspirations to market values, religious impostures, universal boredom, and misery.”

—Franklin Rosemont, André Breton and the First Principles of Surrealism

Surrealism and the Anarchist Imagination is Ron Sakolsky’s most recent book in a string of texts exploring different aspects of the fertile crossroads of surrealism and anarchism. It contains fifteen pieces, ranging from poems and collective manifestos to longer essays.

These pieces argue passionately that it is precisely at the crossroads of these two currents that surrealists and anarchists are at our rebellious best. For that insight alone it is a very valuable book. Early on, the surrealists described themselves as “specialists in revolt”, and it is the spirit of total refusal that has kept surrealism a vital force for more than 100 years. The surrealist slogan, “All Power to the Imagination,” rang out in Paris during the revolutionary events of May 1968 and is still ringing today.

Throughout the book Sakolsky gives examples of the intersecting of anarchist and surrealist currents. From the anarchist/feminist/surrealist publication The Debutante to the visual art of Maurice Spira; from anarchist involvement in indigenous land defence to Hakim Bey’s concept of the Temporary Autonomous Zone, which was influenced by and critical of surrealism.

In Undoing Reality, Sakolsky examines the surrealist concept of miserabilism and his related concept of mutual acquiescence. It is crucial for us to reject miserabilism: “a way of life rooted in the rigid assumptions of a status quo finality that constitutes ‘reality.'” Sakolsky points to John Clark (and his surrealist alter-ego Max Cafard) as seeking “to subvert such realist thinking by examining the miserabilist basis of the ubiquitous popular culture meme of ‘It is what it is!'”

Clark argues, “From the viewpoint of dialectical thinking, the crucial challenge is to see the ways in which things are not what they are. It always is what it isn’t and isn’t what it is. Getting trapped in the world of ‘it is what it is’—what I call Isisism—is the royal road to delusion, disaster, and domination. The right road to illumination and liberation is what I call Isisntism.”The essay ponders the “question of why we are willing to surrender our individual and collective autonomy to the repressive demands of ‘reality’.” Equally important, it examines what tools anarchism and surrealism can provide us to resist and overturn this “absence of the will to revolt.”

Free Jazz: Imagining the Sound of Surrealist Revolution is the longest essay in the book and a tour de force of radical scholarship. It provides all the facts that you need, but suffused with rebellious energy. Surrealists value free jazz because “as a musical form of insurrection, free jazz improvisation is a convivial creative practice that fully embodies the surrealist search for a revolution of the mind (which pointedly includes a critique of the dreariness of the commonsensical in favor of an explosion of the insurgent imagination) and is emblematic of the flowering of its libertarian aspirations for society as a whole.”

Sakolsky points to these aspirations as having a “particularly powerful resonance with the Black Liberation movement.” Archie Shepp is an example given of a free jazz musician dedicated to Black Liberation who also had a strong connection to surrealism, but he isn’t the only one. There is a long list of prominent figures within free jazz who have had short or long term connections with surrealism.

Joseph Jarman and Henry Threadgill were participants in the 1976 International Surrealist Exhibition in Chicago and both composed pieces specially for the exhibition. Doug Ewart’s Sun Song Ensemble performed there as well. Pianist Cecil Taylor was in attendance at the exhibition and also contributed to Arsenal: Surrealist Subversion, the international journal of the Chicago Surrealist Group. William Parker, who played with Taylor for more than a decade, is quoted in the piece as saying, “black surrealism is a vision that has come to me most of my life.” Sakolsky invokes the potent mixture of radical political vision and the visionary power of the human imagination present in free jazz. “In combination, these improvisational acts can provide the sparks that ignite the powder keg of surrealist revolution.”

Opening the Floodgates of the Utopian Imagination: Charles Fourier and the Surrealist Quest for an Emancipatory Mythology is another of the long essays in the book. It discusses the work of 19th century Utopian Socialist Charles Fourier who has been a figure of fascination for surrealists and anarchists alike. Sakolsky explores the history of surrealist engagement with Fourier starting at the very beginning of the Paris Surrealist group in the 1920s.

Fourier’s refusal to be limited by political realism infuriated his later critics Marx and Engels but has endeared him to anti-authoritarians. Fourier dreamed so wildly that he imagined the political equality of women and coined the term feminism. He imagined a world of passional attraction and refused to be limited by the tyranny of what is (deemed) possible.

The essay also discusses the rejection by progressive movements of mythology, which French philosopher George Bataille saw as one of the factors that led to the spread of fascism. The lack of any emancipatory myth left a vacuum for the fascist nightmare. Recent translations into English of Bataille’s journal Aciphale, as well as public lectures that he gave around the same time, have provided more detail of his thoughts on this subject. Sakolsky argues that Fourier could provide at least parts of an emancipatory myth for anarchists and surrealists. It is very heady stuff and a fascinating discussion.

The third long essay in the book is Chance Encounters at the Crossroads of Anarchy and Surrealism: A Personal Remembrance of Peter Lamborn Wilson A.K.A. Hakim Bey. It is a remembrance of Sakolsky’s 35 year long friendship with Wilson. As the title implies, it provides details about Wilson’s engagement with and critique of surrealism, and how Wilson’s critiques encouraged Sakolsky’s own explorations of the crossroads of surrealism and anarchy.

It is a touching tribute to Wilson, a long-time anarchist comrade of Sakolsky’s, not to mention prolific author and contributor to Fifth Estate.

The shorter pieces in the book have a lot to offer too. A Spark in Search of a Powder Keg: An International Surrealist Declaration is a strong reminder that the surrealist movement is vibrant, not a dead historical art avant garde. It provides a glimpse of the internationalism of surrealism. There are signatories from the US and Canada, Central and South America, North Africa and the Middle East, Australia, and all over Europe. It highlights the surrealist spirit of total refusal in opposition to Canadian pipeline projects and the violence of the police. The declaration is a strong voice for solidarity with Indigenous land defence and radical environmentalism.

It is well known that André Breton and many of the French surrealists had an interest in and affinity with West Coast Indigenous art. The declaration states: “as surrealists we honor our historical affinity with the Kwakwaka’wakw Peace Dance headdress that for so long had occupied a place of reverence in Breton’s study during his lifetime before being ceremoniously returned to Alert Bay on Cormorant Island by his daughter, Aube Elleouet, in keeping with her father’s wishes.”

The authors also draw connections to outrage and resistance in response to the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis which occurred during the period that signatures were being gathered for the declaration. A postscript points out that it “was only fitting that in solidarity with the uprisings about police brutality kicked off by George Floyd’s execution/lynching at the hands of the police, anti-racism protesters in the United States would take direct action by beheading or bringing down statues of Christopher Columbus, genocidal symbol of the colonial expropriation of Native American lands.”

Uncovering the Surrealist Roots of Détournement is an excellent short examination of what the Situationists termed detournement, the subversive appropriation of popular imagery, usually a comic combined with radical text, and its roots in surrealist practice. The piece is accompanied by an example of contemporary anarcho-surrealist detournement, a collaboration between Sakolsky and John Richardson. The same image and 20 others, along with an introduction by Sakolsky can be found in their recently co-authored book Surrealist Détournement, published by Dark Windows Press.

Surrealism and the Anarchist Imagination benefits from a beautiful printing job by Eberhardt press and full color art throughout by Rikki Ducornet, Maurice Spira, Zigzag, Peter Lamborn Wilson, Sheila Knopper and many others, which contributes greatly to the effect of the book. Surrealist visual art is a powerful aid to help fire the anarchist imagination.

David Tighe is an anarchist, mail artist, and zine maker living in Alberta, Canada.

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

Sunday, January 26, 2020

Surrealism, Occultism and Politics: In Search of the Marvellous, ed. Tessel Bauduin, Victoria Ferentiou and Daniel Zamani (Routledge, 2018). Studies in Surrealism (Series editor: Gavin Parkinson), , 2018

M. González Madrid

Among the published writings of the artist Remedios Varo there is one letter addressed to a “Dear Mr. Gardner”. Scholars of Varo’s work have long interpreted the letter as an amusement of the author’s, one of her many missives written to people she did not know. However, a recent study has identified this “Mr. Gardner” as Gerald B. Gardner, whose books Witchcraft Today and The Meaning of Witchcraft describe the rituals and beliefs of modern-day witches. In her letter, Varo describes how Miss Carrington “was kind enough” to translate the book for her, and that it had prompted her “great interest”. The identification of this character opens up new readings of Varo’s work.

Varo’s fascination with magic and hermeticism was cultivated together with other artists and writers of the Parisian surrealist group, particularly Benjamin Péret, Óscar Domínguez and Victor Brauner. In both her Parisian work and the work that made her famous in her Mexican exile, one may trace signs of her knowledge about magic, clairvoyance, dreams, automatic “magic dictation”, divination, astrology, alchemy and witchcraft. Moreover, Varo — and other female surrealist artists—were often described as sorceresses , in keeping with the masculine surrealist tradition which, based on Michelet’s La Sorcière, figured the witch as a woman who was wise, rebellious, enigmatic… and beautiful.

Sunday, March 09, 2025

All-female exhibition aims to restore women’s voices in art history

Poitiers – French artist Eugénie Dubreuil has collected more than 500 works by female artists, beginning in 1999. Last year she donated her collection to the Sainte-Croix Museum in Poitiers, which is now putting them on display in an exhibition that aims to restore the forgotten voices of women in art.

02:59

The "La Musée" exhibition at the Sainte-Croix Museum in Poitiers, western France.

© Ville de Poitiers

By :Isabelle Martinetti

Issued on: 08/03/2025 -

RFI

"Women artists have long been marginalised in art history courses and by museums and galleries," Manon Lecaplainn, director of the Sainte-Croix Museum, told RFI. "For decades, art history has been written without women. Why should our exclusively female exhibition be shocking?"

"Our aim is not to exclude men from art history," she explains. "The goal is to make people think."

Eugénie Dubreuil en mariée (1990) by Danièle Lazard. © Musées de Poitiers, Ch. Vignaud

The Sainte-Croix Museum has been known in France for its proactive policy of promoting women artists since the 1980s.

In this new exhibition, Lecaplain and her co-curator Camille Belvèze are showcasing nearly 300 works from the 18th century to the present day, divided into three sections: the collection of Eugénie Dubreuil, the hierarchy of genres in art history, and the social role of the museum.

Spotlight on Africa: celebrating female empowerment for Women's History Month

This exhibition is the first step in a five-year project to promote Dubreuil's collection – entitled La Musée – and relies on a financial grant of €150,000.

"Why not an initiative like this on a larger scale in France, Europe, the world?" asks Dubreuil.

► La Musée runs until 18 May, 2025 at the Sainte-Croix Museum in Poitiers.

Friday, February 16, 2024

By Suyin Haynes, CNN

Thu February 15, 2024

Photographer Suki Dhanda's "Untitled" from the 2002 series "Shopna," features in Joy Gregory's new book "Shining Lights." Courtesy the artist/MACK

CNN —

The genesis of photographer Joy Gregory’s latest project, “Shining Lights,” began 40 years ago, at a Valentine’s Day party in London. It was here that Joy, who was the first Black woman to study an MA in Photography at the Royal College of Art in London, first met activist and writer Araba Mercer. After the party and as they became friends, Mercer suggested the pair collaborate on a book about women’s photography.

“I knew lots of photographers who were emerging at that time,” Gregory recalled over tea in a cafe near her studio in south London. “So I persuaded all of the people I knew to submit work.” They presented their plan for the book — comprising the photographs gathered by Gregory, and text by Mercer — to Sheba, a feminist publishing collective focused on Black women’s storytelling that Mercer was a key member of. Sheba was enthusiastic, but the cost of printing all the submitted photographs ultimately proved prohibitive.

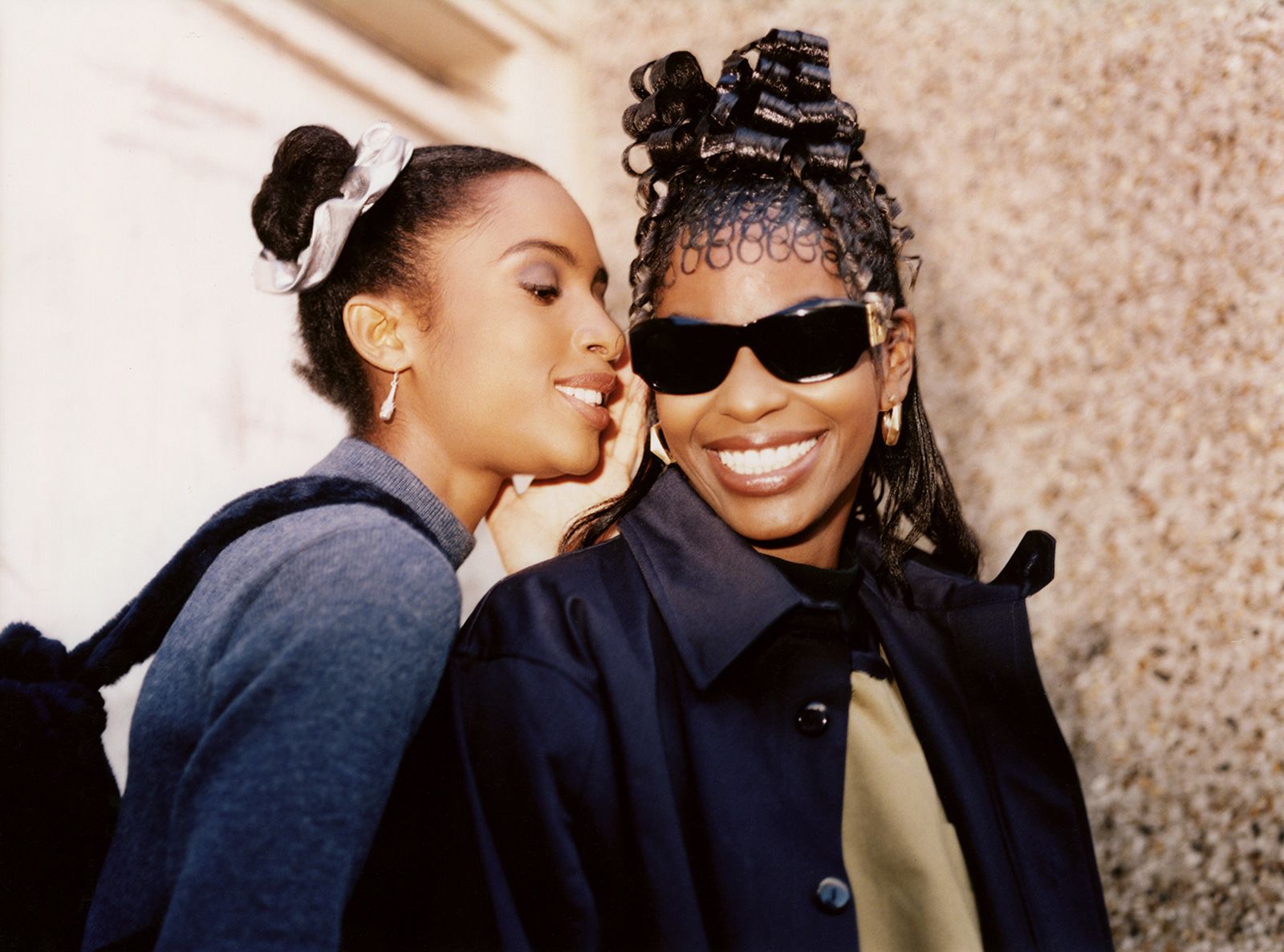

Jennie Baptiste's image "Portrait of two girls from a series for Fashion Designer Wale Adeyemi MBE," 1995. Courtesy the artist/MACK

The idea then, for a book surveying the work of Black women’s photography in Britain in the 1980s and 1990s, lay dormant for several decades. But a 2019 talk Gregory gave at Autograph gallery in London about photographer Maxine Walker’s work sparked renewed interest in the contribution of women of color to photographic art during this period.

The result is “Shining Lights: Black Women Photographers in 1980s–90s Britain,” a new photography book edited by Gregory and co-published by Autograph and Mack. Divided into thematic chapters exploring community and activism, kinship and family ties, travel and landscape photography and more, “Shining Lights” features 57 photographers, capturing the rich breadth of work from this overlooked period and community.

Telliing the stories no-one else was

The book includes work by well-known artists such as Walker, whose photographic practice centres on representations of Black womanhood, surrealist artist Mona Hatoum, and Turner Prize nominee Ingrid Pollard, whose images in the book use portraiture to examine gender and sexuality.

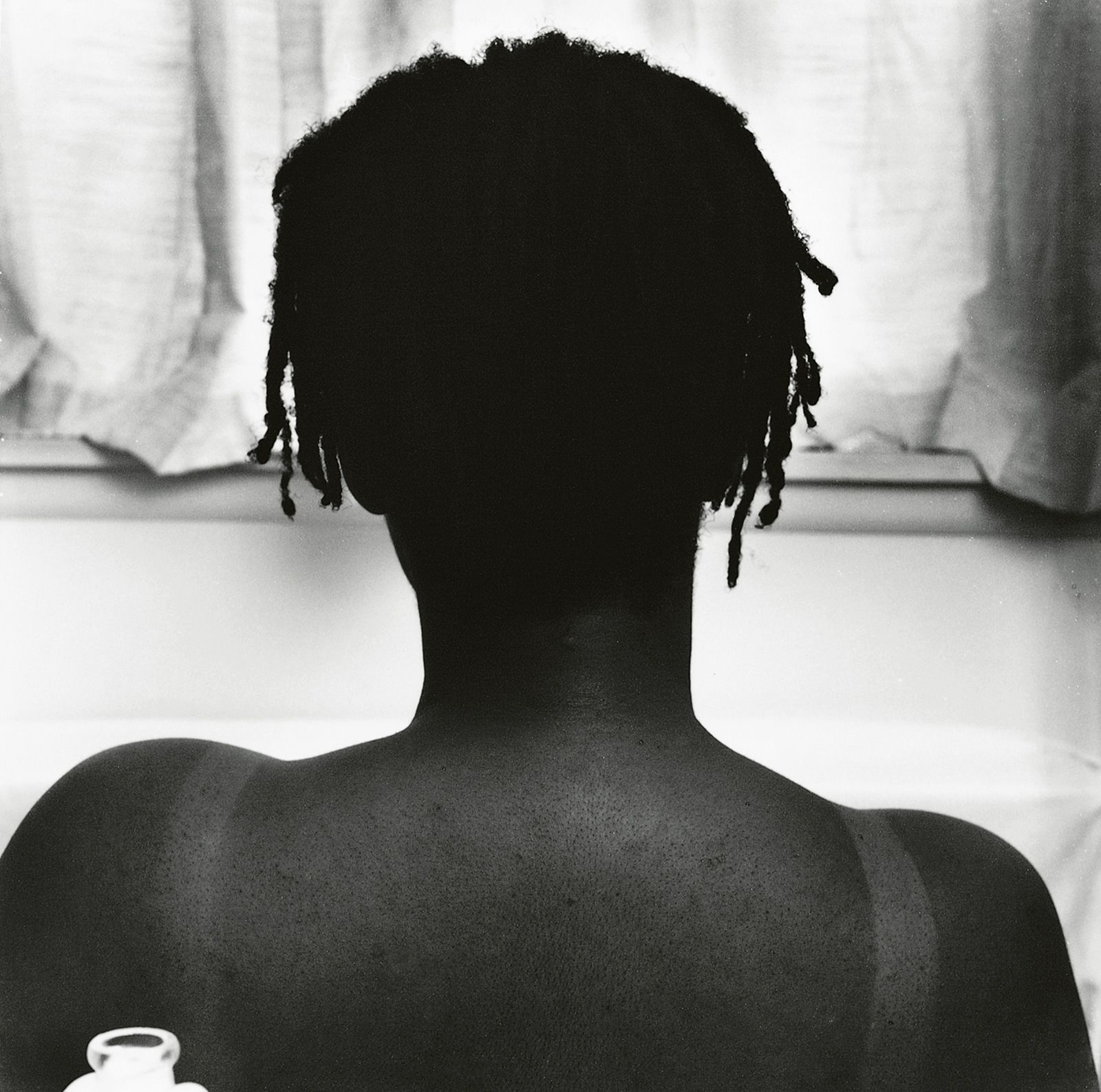

"Her" by Maxine Walker, from the series "Black Beauty," 1991.

As well as casting the work of these artists in a new light, the project also introduces readers to photographers working during that time who are perhaps not as well known. Examples include Jacqueline Moran Daubercies, whose vibrant photographic practice focused on Latin American women and children, and Maria Pedro, whose poised self-portraits in the book reimagine herself as historical Black female royalty.

“What’s really interesting about history, and the way that history is recorded, is there’s always heroes, but actually, it was a collective,” Gregory told CNN in an interview. “And I think a lot of the collective has been written out of the history.”

“Shining Lights” then is Gregory’s considered effort to write in that missing history. Reconnecting with old networks and contacts to gather the material for the book was a meticulous task, with Gregory posting callouts in her own Facebook group as well as others and spreading the word around different creative networks.

Eileen Perrier's "Ghana," dating to 1995-96.

She says that while some of the book’s contributors are now recognizable photographers, others have moved on entirely from photography since that era. Some had forgotten or not revisited their work during the interim decades, or had even lost large portions of their work. Gregory recalls one contributor arriving at her studio with three big bags of undeveloped negatives, consisting of close to 10,000 images. “That’s basically an entire book there, but again, that’s one of the people that’s completely disappeared from view.”

“That was the problem with going back and looking at the magazines and publications that were produced in the 1980s to try and find a trace of the women that are in this book,” said Gregory. “That wasn’t there because they weren’t picked up at that time, and nobody was telling their story.”

Joy Gregory, "Junie - Kingston, Jamaica, 1997," also features in her new book Shining Lights. Courtesy the artist/MACK

For some of the book’s contributors, Gregory says, revisiting that time and the poor treatment they received from the industry was painful. “It was reliving those disappointments…people were traumatized by the experience, and that wasn’t surprising, but it was shocking, in a way.”

An inaccessible medium

This era for Gregory, who was awarded the prestigious Freelands Award in 2023, was foundational. “I think I wouldn’t really have a practice without that period, obviously,” she said. Her own photographic series, “Autoportrait,” features in the book; originally made in 1990, it consists of a series of nine self-portraits of Gregory posed at various angles, looking both directly into and turned away from the camera.

She recalls how those among her network were often shut out of inaccessible arts institutions and forced to work at the margins. “Now, everybody has access to photography with their mobile phone; then it was a much more technically inaccessible medium,” she said.

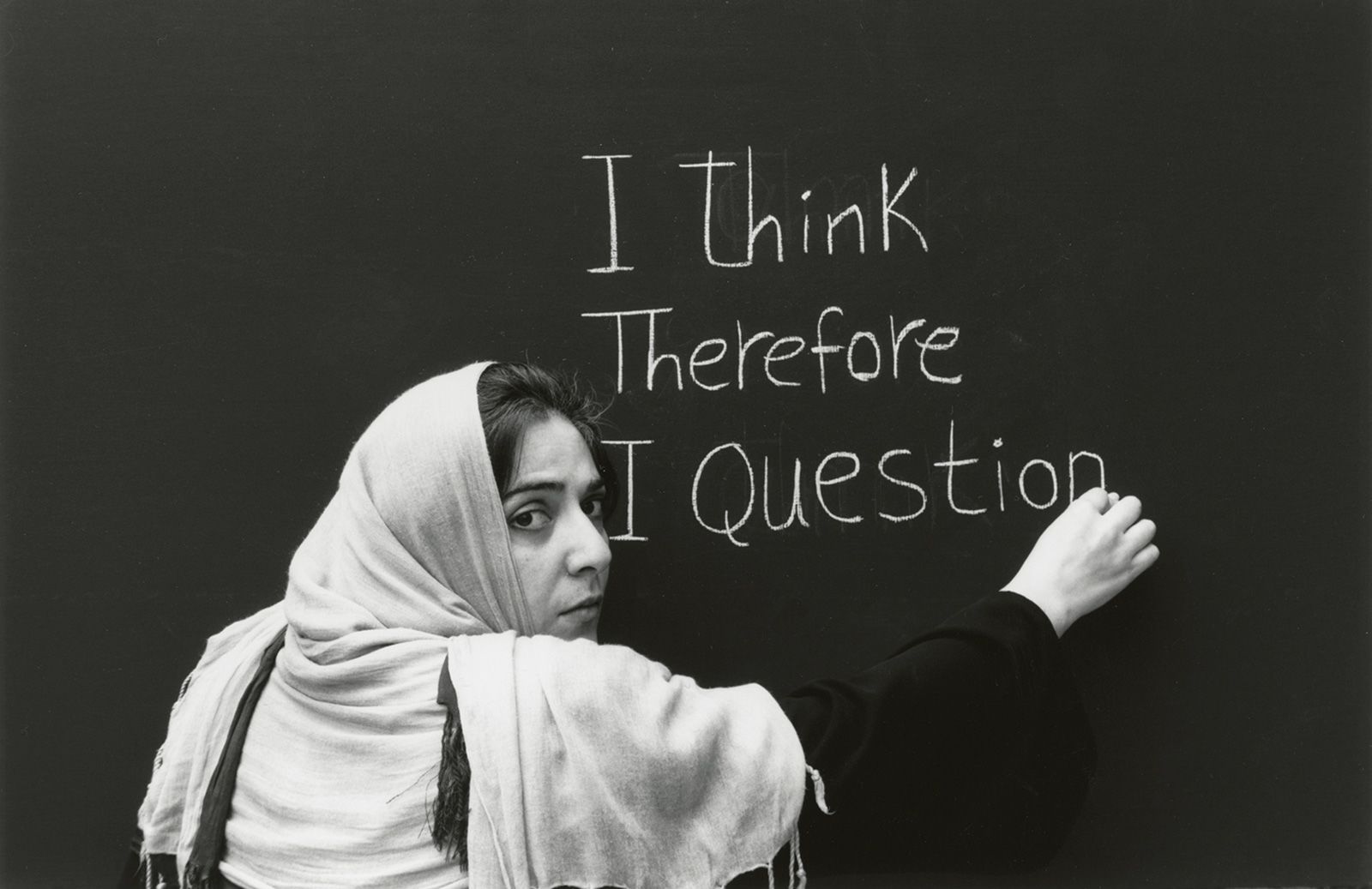

Maria Kheirkhah's image titled "I Think Therefore I Question," from 2002-03.

Often faced with disappointment and rejection, these photographers rallied together. “There was a move to actually educate and help each other, and there was a lot of sharing of materials and knowledge,” she said, adding that community centres played an important role in offering space for learning. Gregory gives one example of photographer and curator Mumtaz Karimjee teaching herself how to do cibachrome color printing, and then teaching others in the network the same skill.

“The way in which people supported each other was really important — well, essential — because the other networks were not open to us,” said Gregory. “I think as women, it wasn’t open, and I think being of color, it definitely wasn’t open.”

In the book, Black “refers to the whole gamut of color, which was really about difference,” says Gregory. “Anybody who was different and seen as outside was included under that title Black, and it was more of a political identity, more than anything else.”

An installation view of Virginia Nimarkoh's "Afrotopia 1," from 1991.

A 1987 essay written by Karimjee and included in the book explains this definition and feeling in more detail. It’s one of several contextual essays and conversations in “Shining Lights,” both from the present day and from the 1980s and 1990s, on themes including the abuse of power in photography, identity in British arts and cultural production, and change and continuity for new generations.

On this note, Gregory feels that in some ways, the landscape today remains similarly inaccessible, meaning that the enterprising, do-it-yourself attitudes of the 1980s and 1990s are still present among new and emerging artists. One example featured in the book is photographer and filmmaker Ronan Mckenzie, who established her own independent exhibition space, HOME, in London in 2020.

Joy Gregory's "Autoportrait 1990 / 2006," also features in the book.

“I feel that a lot of the issues that we were dealing with in the 1980s haven’t gone away, and I think to include those essays actually highlights that,” said Gregory, adding that she hopes it will be encouraging for younger artists to see the work, perspectives and leadership of those who have preceded them.

While Gregory played a vital role in the book’s creation with support from associate editor Taous Dahmani, she emphasizes that it’s more about the dozens of photographers whose work is finally receiving overdue recognition

“The book is women in their own voices,” said Gregory. “That’s what I wanted to bring. So in a way, I feel that this is not my book. This is their book.”

Shining Lights: Black Women Photographers in 1980s–90s Britain is published by Mack and Autograph

Friday, February 14, 2020

TOWARDS THE HISTORY OF SURREALISM BOREAL;

– a reasoned chronology in three parts of surrealist initiatives and some parallels

in Sweden (with outlooks to its neighbouring countries)

Mattias Forshage

Part 1

When the artists and writers were still searching 1924-50 – the introduction of surrealism and the early encounters with the surrealist movement

Home - Texts - Galleries - Other media - Links - Contact

Texts in English

POETRY

Riyota Kasamatsu - Askew clang blind bang

John Andersson - There's a nightly rainbow

John Andersson - A master confesses

EL and Fantom - Exquisite cadaver

Collectively - Nicolas Flamel’s Journeys

NN, MF, RK - Three poems from The Vagrant#1 2000

Merl Fluin - Between the Exhibits

Merl Fluin - Poetic Standpoints

Merl Fluin - Loveletters to Rumpelstiltskin

Emma Lundenmark - Translation from an Imaginary Language

Emma Lundenmark - The Chair About the Sound Macrabet

Emma Lundenmark - Wings (Into the Open Field)

Mattias Forshage - The Future of Polar Research

Mattias Forshage - Tesseract 2, My Elusive Polish Offices

Mattias Forshage - Train Poems

Robert Lindroth - Automatism / Unexpected Directions

COLLECTIVE DECLARATIONS:

Scream in the sack - from Lucifer 2000

Open letter to Guy Girard - discussing Guy Girard´s constructive critique of "The Scream in the Sack", 1999

Voices of the Hell Choir (HTML) - aspects of contemporary surrealist activity, its modes of rhetoric and its ludicism, 2003, VotHC Integral edition (PDF)

EDITORIALTEXTS FROM THE VAGRANT:

* 1- 4, 2000-2003

EDITORIAL TEXTS FROM STORA SALTET:

* C-M Edenborg: Matter - Nr 1, june 1995

* Mattias Forshage: Geography - Nr 2, sept. 1995

* Bruno Jacobs: Scars - Nr 3, dec. 1995

* Aase Berg: Ruage - Nr 4, march 1996

* Mattias Forshage & Aase Berg: Surrealism in the Ulterior Times - Nr 4, march 1996

La Source Bouchée (en français; in french) - about the jubilee of the swedish state church, 1993

Paper, Scissors, Stone?- surrealism and politics, 1995

The Smoke of the Dignity of Man - about man-movements and neo-fascism, 1995

The Public Sphere and Curiosity- from 1991 Surrealists, 1995

VARIOUS THEORETICAL TEXTS

No Music! - Johannes Bergmark, 2004.

Butoh - Revolt of the Flesh in Japan and a Surrealist Way to Move, 1991. With introduction 2008 and appendix 1993 - Johannes Bergmark

Labors of Existence - Merdarius

Surrealism is a Shrimp - Merdarius, 2008

Surrealism and Science - Merdarius, 2008

The surrealist bestiary - Mattias Forshage, 2009

To the question of surrealism and women - Mattias Forshage, 2008

What about the surrealismologists - Mattias Forshage

Soluble locus - Mattias Forshage, 2008

Surrealism and the holy 'nuff - Jonas Enander, 2008

Atheism as the metaphysics of experience - Niklas Nenzén, 2008 The place of the soul- John Andersson and Niklas Nenzén, 2006

Contribution to the investigation of the tropes of pansexuality - Mattias Forshage, 2004

Worthless Places (Atoposes) - Mattias Forshage, 2004

Fragments sur le vandalisme - la pertinence sociale de l'asocial - Mattias Forshage, Lucifer 2000

A reminder of the desire simulation industry, the mechanisms of recuperation and the battle over the advertising space referred to as der Geist - Mattias Forshage, from Lucifer 2000

Call For The Hidden Sounds - Johannes Bergmark, 1994-95

For A Wild Music - Johannes Bergmark, 1993

Roxanne (en français; in french) - pornography and alchemy - Carl-Michael Edenborg

The Situation of Sexuality Today or the Sublimization of the Production of Children - Johannes Bergmark, from Kvicksand 1 1989.

GAMES AND EXPERIMENTS

An enquiry from the bewitched - Answering questions by anagramming them, 2007 The firefly in the peppermint rock hand - successive pattern interpretation, from Lucifer 2000

Phenomenology of fear - A spontaneous interpretative exploration of fears in pictures and in words, 2004.

Objectification of Morals - Language-materialistic renegotiation of abstract concepts, from Lucifer, 2000

Animal Walks - Identifying with a random animal while taking a walk, 2007

Casa Synestetica- Constructing a surrealist house by the means of synesthesia, 2006

Exploration of an island - geographic game - the subjectivisation of material topography,1999