Rûken Nexede of the KJAR said that the women's struggle in Iran and East Kurdistan continues. Inspired by Öcalan’s philosophy, a great social awakening has taken place.

HEWRÎN CENGAWER

NEWS DESK

Tuesday, 19 November 2024,

East Kurdistan, which is ruled by the Iranian regime, is a focus of women's resistance. The 'Jin Jiyan Azadî' revolution was initiated by the women of East Kurdistan. The region is a place of both determined resistance and the harshest repression. On the occasion of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women on 25 November, Rûken Nexede of the Community of Free Women of Eastern Kurdistan (KJAR) spoke about the prospects of women's freedom struggle.

"An unprecedented level of women's struggle"

First, Rûken Nexede paid tribute to the people who lost their lives in the fight against patriarchy and emphasized that the existence of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women is the result of the anti-patriarchal women's struggle. She spoke about the special level that the women's struggle has reached today, and said: "Today there is a general women's organization, women are discussing confederalism, they are expanding their knowledge of military organization. Women have reached a level in the 21st century for which we can proudly congratulate them on their resistance and uprisings. With the emergence of the apoist movement, many achievements such as the women's revolution, the military organization of women and the science of women have been realized."

"Women have never submitted to patriarchy"

Nexede added: "Throughout history, women have not submitted to patriarchy either spiritually or intellectually. Through Rêber Apo [Abdulla Öcalan], women returned to their true nature and learned how to fight against the patriarchal mentality, organize themselves and build a free life. The apoist women's movement was organized from this awareness and continues to fight on this basis today. Rêber Apo defined the 21st century as the women's revolution. We are proud of all the women's struggles that have taken place up to now. All of these struggles were fought with great difficulties and sacrifices. This struggle was fought by our martyrs like Heval Roza, Heval Sara and Heval Şîrîn in the prisons, mountains, cities and villages. With their heads held high, women emerged from the darkness with the philosophy of Rêber Apo."

"A free life means true love"

Nexede continued: "Rêber Apo described the personality of free women and men in a way that we can see in the sacrificial attitude of Heval Asya and Heval Rojger. Their willingness to make any sacrifice is so meaningful that we do not know how to appreciate them sufficiently. From the personality and actions of these comrades, we can see that a free life means true love. Therefore, I would like to pay tribute to them once again for the level of freedom they have achieved. The way to honor these martyrs is to also attain this level of freedom. In order to build a free life, all women should adopt these actions."

"Every place that Apoism reaches experiences a change"

Nexede said: "With the 'Jin Jiyan Azadî' revolution, women recognized the lost will and power of the people. At the same time, questions arose for both women and men: Who am I, how do I live, what do I live for and where do I live, what is domination, what is violence? This revolution made everyone question themselves. Artists questioned what their art was for; scientists began to investigate what science was and who it served. There was discussion about the extent to which the state was using science for its own interests. Everyone began to ask questions."

"Fear was defeated"

Nexede said: "Families began to question what family meant, what the roots of the family concept were and what it was for. The predetermined role of women, girls and boys was questioned. Students began to question how they learned things and whether it was for life or in the service of the system. Rêber Apo's philosophy brings about change wherever it reaches. The Iranian regime is currently desperate, it has no more resources and is in crisis. The pressure on society is great. Women and young people are massively oppressed under the guise of religion. But people have now seen the true face of this regime, they are taking a stand and fighting without fear. Although they know they may fall as martyrs, they continue to fight, make no compromises and sacrifice themselves for the freedom revolution."

TJK-E called on all women to participate in the actions and events they will hold on the occasion of 25 November International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.

ANF

NEWS DESK

Monday, 18 November 2024, 12:02

The European Kurdish Women’s Movement (TJK-E) issued a written statement on the occasion of 25 November International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.

TJK-E said: “We welcome 25 November 2024, with the slogans ‘Jin, Jiyan, Azadi’ rising all around the world. With the great struggles of women who say another world is possible, the patriarchal-statist system is being shaken from its roots today. On the occasion of 25 November International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, we remember with love and respect all women who resisted, worked hard and paid the price on this path, from the Mirabel Sisters to Sara, from Hevrin Xelef to Jîna Amini, who were the expressions of insistence on a free life against the fascist Trujillo regime. Their determination, love and struggle for a free life continues to grow in women’s struggle for freedom today.”

The TJK-E added: “We are going through a time when the Third World War is making itself felt the most. Women are the ones who suffer the most from the reality of war that has seeped into the daily life of society; from the attacks and policies developed by the nation-state, capitalist modernity and the patriarchal system in a multi-layered and multi-faceted manner. The Third World War, which developed as a result of the existence and interests of hegemonic powers, concerns us Kurdish women the most, both because its center is in the Middle East and because misogynist policies are being brought to the top. For this reason, the task of developing our own self-organization, self-policy, self-defense, and creating alternatives in terms of social, economic, cultural and educational aspects, as well as resisting genocidal attacks, is more urgent than ever. This urgency determines the essence of our struggle as Kurdish women.”

We will expand the struggle against attacks

The statement continued: “We, the European Kurdish Women's Movement (TJK-E), are aware that women are targeted in the Third World War, and that women's self-defense must be developed.

We see 25 November as a day when our continuous struggle reached its peak, when women's organization, actions and creations reached their peak.

As Kurdish women living in Europe, we say that we will defeat the trustees who disregard the will of women in Bakur, the execution policies of the Iranian regime, the invasion plans for Rojava, the betrayal in Bashur and isolation in Imrali. On this basis, we call on all women to participate in the actions and events we will hold with great enthusiasm and to make the streets in every country in Europe resound with the slogan “Jin Jiyan Azadi.”

Events are being held in many centres in North-East Syria to combat violence against women on the occasion of 25 November, International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.

ANF

QAMISHLO

Monday, 18 November 2024

On the occasion of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women on 25 November, the autonomous region of North and East Syria is holding a series of events over several weeks. This year's activities by the women's associations in the region are under the motto ‘Defend yourselves with the Jin-Jiyan-Azadî philosophy’ and aim to raise awareness in society and empower women through education and high-profile actions.

Hundreds of men took to the streets in Qamishlo and staged a march with slogans condemning violence against women.

The march from Sonî Junction to Martyr Rûbar Junction was participated by hundreds of people from civil society organisations and many institutions of the Democratic Autonomous Administration.

A press statement made on behalf of Kongra Star highlighted Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan’s thoughts on women's struggle and pointed out that society needs free women.

Referring to the meaning of 25 November, Cewahir Osman said, “The ruling forces impose violence on society in the person of women. Violence against Leader Apo (Abdullah Öcalan) is violence against all women. We say enough is enough and we say that you cannot break our will as a people.”

Another speaker, Xufran Tewkeb, who addressed the crowd pointed out that women struggle for freedom all over the world and stated that violence must be rejected.

Xufran Tewkeb stated that Öcalan’s ideas and philosophy are the source of the struggle for women's freedom and emphasised that women will continue this struggle in the strongest way.

ANF

NEWS DESK

Monday, 18 November 2024

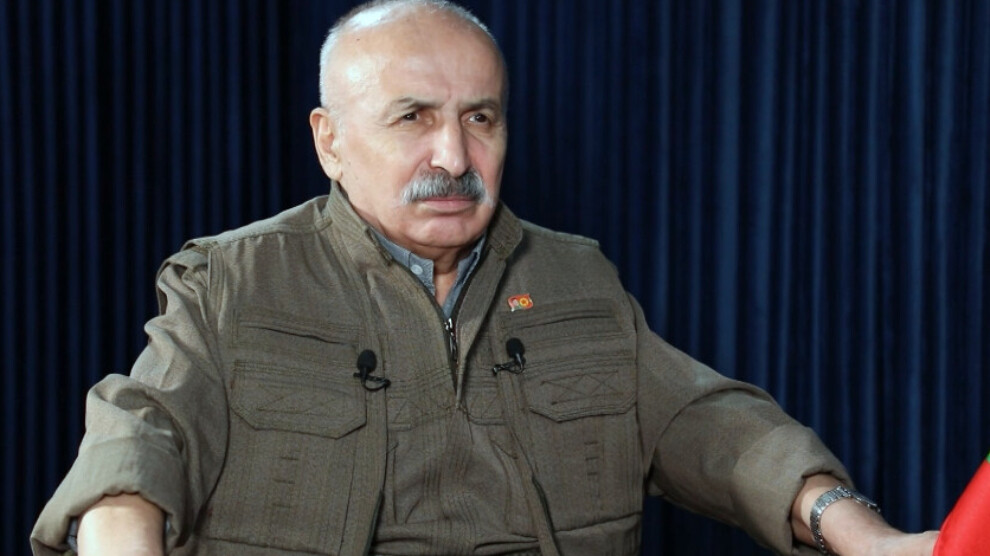

In the third part of this interview, Mustafa Karasu, member of the KCK Executive Council, talked about the upcoming 25 November, International Day Against Violence Against Women, as well as the 27 November, the anniversary of the founding of the PKK.

The first part of the interview can be read here, the second here.

We are currently approaching an anniversary, namely November 25, the International Day Against Violence Against Women. What do you have to say in this context, especially to men?

The women’s issue is, of course, an important cause. Violence against women is a thousand-year phenomenon. Violence against women is a historical phenomenon, and one can say that it is one of the oldest problems of society. In fact, it is the source of all other problems. The source of social problems is domination over women. And what is dominance built on? It is achieved through violence, through many forms of violence against women. Rêber Apo speaks of the woman as the first colony. She was treated like the first colonized nation. And has since then been oppressed for thousands of years.

In this respect, this problem is more than just the fact that many men have oppressed women and many men have killed women. It is a social problem that concerns the whole society. It is a problem that needs to be solved. Without the elimination of violence against women, without the elimination of the policy of violence against women, in other words, without women being free, society cannot be at peace. Society cannot be healthy. Where there is violence against women, society is sick and unhealthy. It is a great humanitarian problem to inflict violence on the mother, the one who gives birth and raises the child. A woman is part of society, half of it, and violence is particularly practiced against her. Of course, this must be opposed. One cannot be a democrat, a human being, a moral person, or a conscientious person without taking a stand against this.

Violence against women is a social problem. There is this approach among men. It is an approach that feeds on male dominance and is related to morality and conscience. Men have that tendency. It has been implemented in their genes for thousands of years. It has become a culture of belittling women and practicing violence against women. Every man must know that this culture has infected him, and he must get rid of this evil, this ugliness. This is a very important issue.

Rêber Apo has paved the way for the women’s freedom struggle, and there have been important developments in Kurdistan. But still, in Kurdish society, men’s understanding of violence against women continues. He has not been able to get rid of all that dirt and rust. If Kurdish youths and Kurdish men say that they are loyal to Rêber Apo, if they talk about the freedom of the Kurdish people and democracy, they should definitely change their approach towards women. Men, patriots need to get rid of this tendency to violence against women. Otherwise, their patriotism is incomplete. One cannot be a true patriot, democrat, or freedom seeker; one cannot be conscientious or moral if one doesn’t work on getting rid of this.

The issue of violence against women is important. And when I say violence, I mean it in any aspect. Even raising one’s voice against a woman is violence. Generally, men raise their voices to women when something happens. This is a tendency of masculinity, a tendency to dominance. But there are so many more forms of violence, restriction in social life, not seeing women as equal, exclusion, etc.

On the occasion of the approaching November 25th, I commemorate the Mirabal sisters with gratitude and respect. November 25th has become a day of struggle against violence, and it is having a great impact. It has spread to the world. On this occasion, I condemn all violence against women, and I call on all patriots and democrats to fight against violence against women. All patriots in Kurdistan must avoid violence when approaching their wives, children, daughters, and sisters. This is true patriotism.

Another anniversary is also slowly approaching, the founding day of the PKK, on November 27. For decades, it has been said that the PKK is on the verge of being crushed, but again and again it continues to develop and emerge stronger as before. What can you tell us about this, or about the approaching anniversary in general?

The founder of the PKK is Rêber Apo. Rêber Apo founded, developed, and brought the PKK to the present day on the basis of an ideology that has continuously developed and sustained itself from the first to the present day, that is, on the basis of an ideology that integrates itself with society, integrates itself with the people, integrates the struggle, in other words, ensures that the society embraces the people. It has been 46 years now, and there have even been more before that. For more than 50 years, a struggle has been going on. This has created a culture. The PKK is no longer just an organization or a political party.

Today, the PKK is a social culture, a social mentality, a part of society. In other words, society has also become the PKK. That’s why society constantly chanted slogans like “PKK is the people, the people are here.” This is the reality. It is no longer possible to separate the PKK from the Kurdish people. It is not possible to separate it from Kurdish history. It is not possible to separate it from Kurdish culture. The PKK’s survival at this level, its strong existence despite all the attacks, is the result of this. The PKK is a power beyond its current concrete strength. If the attacks against the PKK fail to achieve results, it is because the PKK is a bigger force than it appears. It is a movement deeply rooted in society.

The PKK has always gotten stronger, is getting stronger, and will get stronger. The PKK is the organized form of Rêber Apo’s thought. Rêber Apo’s thought is a thought that will no longer determine the present but the future. The PKK, which is its organized form, will continue its influence in the future. It has militants like Asya Ali and Rojger Helin. These are the values they have created. There is prison resistance; there is the women’s movement. As Rêber Apo said, the PKK is a women’s party. It is a party shaped on values that we cannot list here. It is delusional to think that the PKK can be destroyed through these and those attacks. That is why the reality of the PKK is a reality that needs to be further researched and analyzed.

The PKK has become a reality beyond us. This needs to be seen. If the PKK were just material assets, concrete realities, the PKK would not be able to survive under so many attacks. The PKK has a spirit that keeps it alive. That power, which is beyond its concrete existence, beyond its material existence, sustains the PKK. It keeps us constantly struggling, and by struggling, we constantly yield results. This cannot be prevented by any attack. On this basis, I salute Rêber Apo once again with gratitude and respect for creating such a party. I also remember with gratitude and respect all our martyrs who have brought the PKK to this day. The PKK will struggle by adhering to their memory and will realize their aspirations.

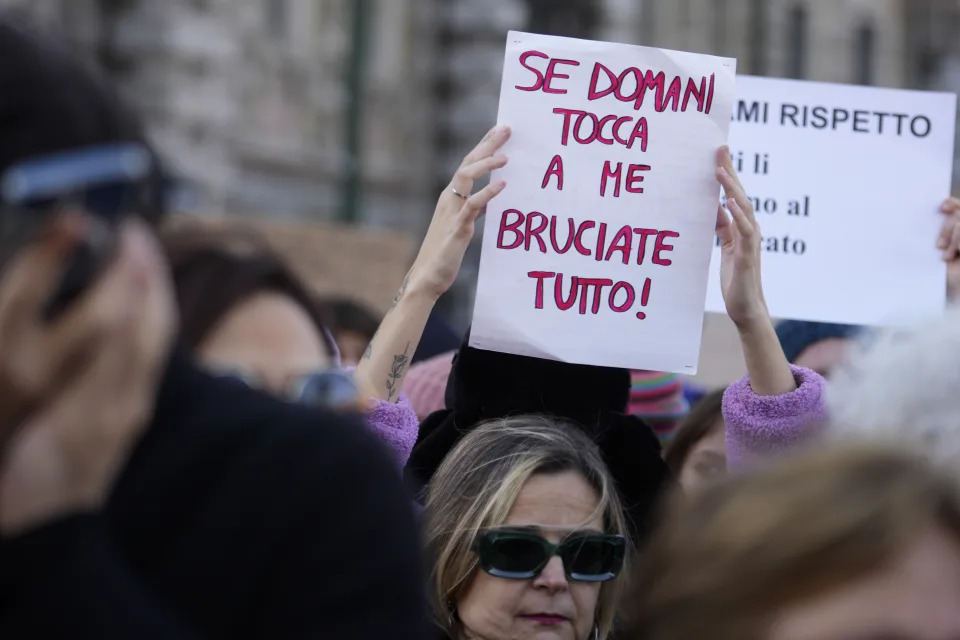

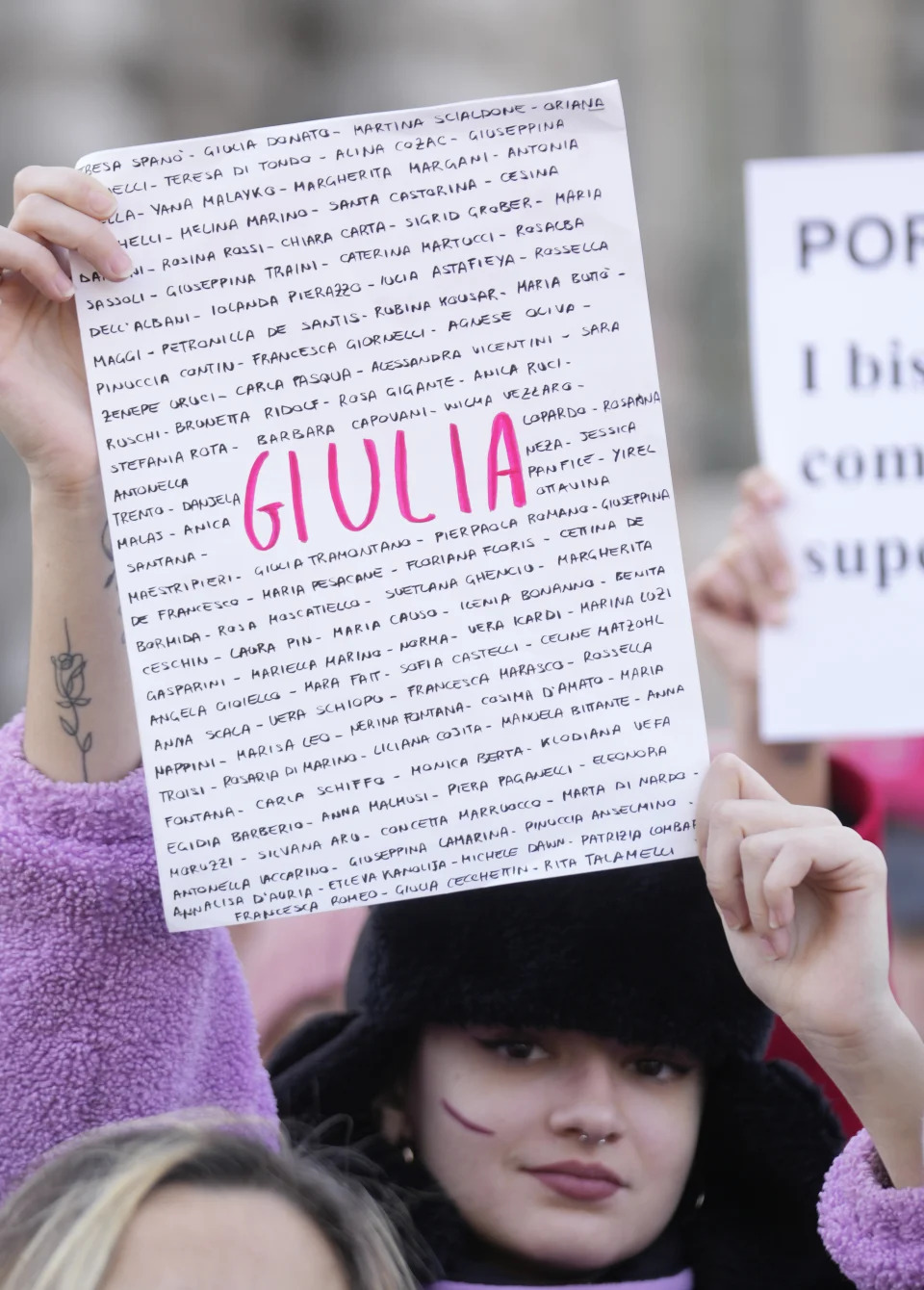

A woman holds a placard that reads "Christmas arrives within the murder of 15 women", in reference to the rate of femicides in France, during a demonstration on the International day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women in Paris on November 25, 2023.

A woman holds a placard that reads "Christmas arrives within the murder of 15 women", in reference to the rate of femicides in France, during a demonstration on the International day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women in Paris on November 25, 2023.