Explained: The complex clash of legal authority, and histories, behind today’s standoffs.

Katie Hyslop Yesterday | TheTyee.ca

Katie Hyslop is a reporter for The Tyee.

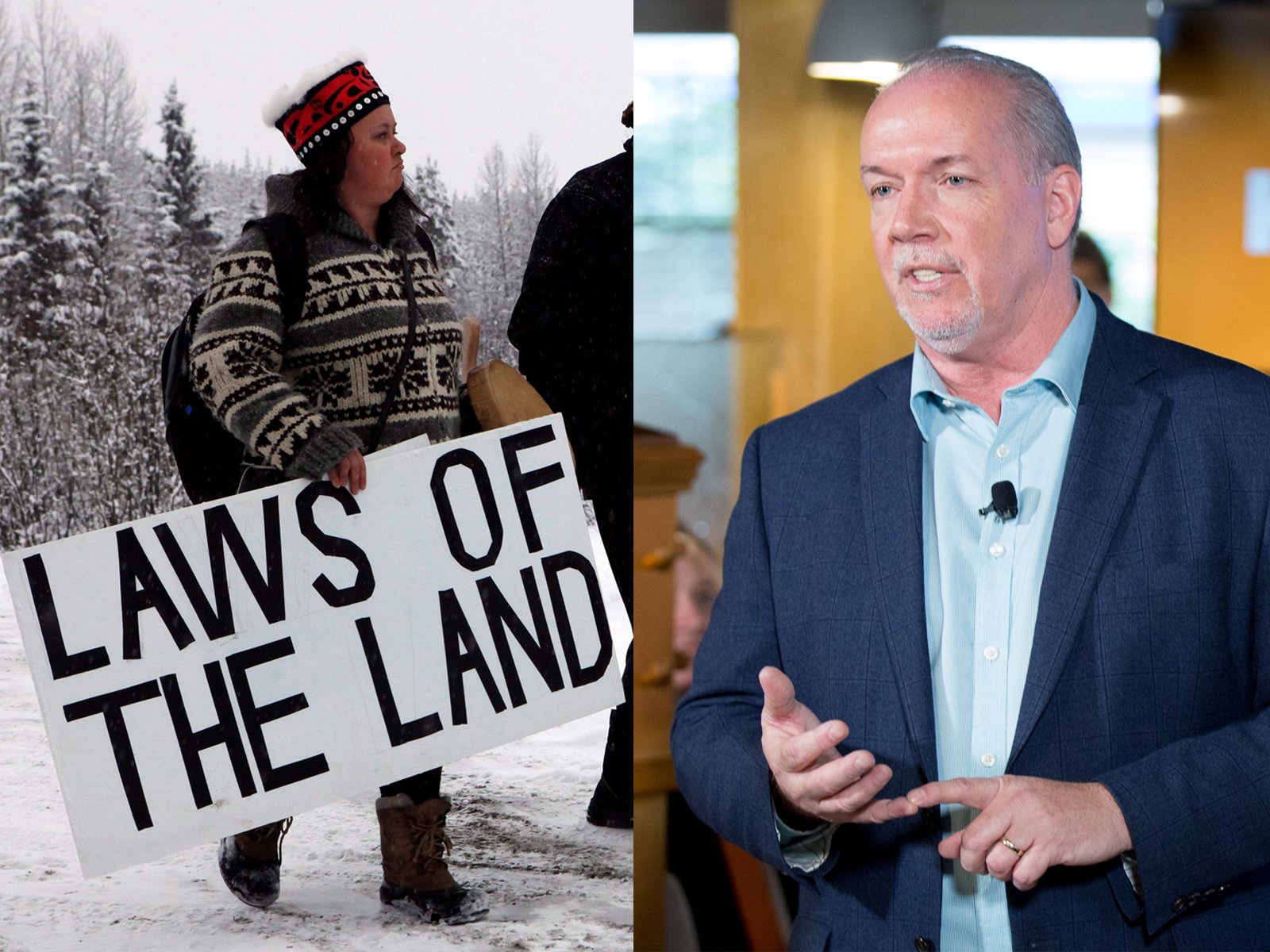

Christy Brown (Gitxsan-Tsimshian) at the Unist’ot’en camp on Wet’suwet’en territory in January 2019. B.C. Premier John Horgan has invoked the ‘rule of law’ in clearing anti-pipeline encampments. Photos: Chad Hipolito, Canadian Press (left) and BC NDP.

Unlike the majority of Canada, most of the territory we now know as British Columbia was never ceded by First Nations who have lived on these lands for at least the last 14,000 years.

In contrast, the Colony of British Columbia, as settlers first called the province, has existed for just over 160 years — less than one per cent of the time First Nations people have lived here.

Except for the Douglas Treaties on Vancouver Island, a portion of northeastern B.C. covered by Treaty 8, and a handful of modern treaties signed since the 1990s, the majority of British Columbia is First Nations’ land that was never covered by a treaty or taken as spoils of war.

Today, there are 200 distinct First Nations occupying their territories in B.C.

Like their lives and cultures, First Nations and Inuit legal systems across Canada were never extinguished, even where treaties were signed. The Supreme Court of Canada has declared these legal systems, unique to each nation, never stopped being valid just because Europeans settled here.

The Tyee is supported by readers like you Join us and grow independent media in Canada

This reality has meant continual clashes between Canadian governments who wish to mine natural resources for profit and jobs, and Indigenous people asserting their right to a seat at the table where decisions are made over how lands and resources are used.

The latest such conflict occurred last week when the Royal Canadian Mounted Police entered the unceded territory of the Wet’suwet’en Nation, 22,000 square kilometres located southwest of Smithers, arresting almost 30 Wet’suwet’en people and their allies.

The police were enforcing a Dec. 31, 2019 B.C. Court of Appeal injunction granted on behalf of Coastal GasLink, a subsidiary of TC Energy, a.k.a. TransCanada Energy.

Last month, following the injunction ruling, B.C. Premier John Horgan announced the Coastal GasLink project would go ahead, telling the media “the rule of law applies” now that the courts had sided with TC Energy.

But on unceded territory, the title of which is claimed by a First Nation living there for thousands of years without signed treaties or surrendering their land, whose rule of law applies? That question drives intensifying debate and protests.

Let’s break down and clarify six elements at play in this legal drama.

1. THE INJUNCTION

The B.C. Supreme Court’s Dec. 31 injunction sided with Coastal GasLink, giving it the right to continue construction on a 400-person “man camp” in anticipation of a provincial permit to construct a liquefied natural gas (LNG) pipeline running from Dawson’s Creek to Kitimat, B.C.

Both the man camp and the pipeline will cut right through untouched Wet’suwet’en territory.

This series of raids is the second time in 13 months the RCMP had raided Wet’suwet’en checkpoints along the logging road leading to the proposed man camp site. The previous raids were in the wake of a temporary injunction granted Coastal GasLink. In both cases arrests were made in the name of Coastal GasLink workers’ safe access to the territory.

Injunctions have proven an effective legal tool in Canada for corporations. The Yellowhead Institute, a First Nations-led research centre focusing on land and governance based in Ryerson University’s faculty of arts, released a report last fall showing of the roughly 100 injunctions they reviewed, 76 per cent filed by corporations against First Nations were granted, but just 19 per cent of injunctions filed by First Nations against corporations were approved.

“Land alienation is linked to the broader political economy of Canada that relies to a significant extent on its natural resource sector to secure jobs and investment. Thus, land alienation is a major economic driver of the Canadian economy,” the report concludes.

2. HEREDITARY CHIEFS AND BAND COUNCILS

Under the Indian Act, those who are recognized by the federal government as having First Nations “status” are grouped into bands, led by a chief and council elected by the band members.

Bands have control over reserve lands, where First Nations were forcibly relocated — sometimes on their own territories, sometimes not — under the Indian Act. Under Canadian law, reserve lands actually belong to the Crown, but bands have jurisdiction over the people and services on those reserves.

Coastal GasLink has signed Impact and Benefit Agreements with 20 Indian Act band councils along the 670-kilometre proposed pipeline route.

Prior to the passing of the Indian Act in 1876, First Nations, including the Wet’suwet’en had their own leadership and legal systems that were ignored by colonial governments, but never extinguished.

While the elected Wet’suwet’en chief and council have jurisdiction over the reserve communities on their territory, the rest of the 22,000 square kilometre territory — roughly the size of New Jersey — is the jurisdiction of the 13 hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en Nation’s five clans: Gilseyhu, Likhts’amisyu, Laksilyu, Tsayu and Gidimt’en.

Between the five clans there are 13 houses, each with their own territory overseen by a hereditary chief. The proposed Coastal GasLink pipeline and man camp are slated for a section of Wet’suwet’en Nation controlled by the Dark House.

Due to the recent passing of two hereditary chiefs — and two hereditary chief vacancies — only nine of the 13 Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief positions are currently filled.

Unlike the hereditary royalty of the British monarchy, Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief is not a lifetime position bestowed on a bloodline. Rather, it’s a title that can be bequeathed a Wet’suwet’en Nation member based on their character and conduct — though this remains a matter of some dispute within the Wet’suwet’en First Nation.

While the elected Wet’suwet’en band council signed an agreement in favour of the pipeline with Coastal GasLink, the nine Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs maintain it is they, not the band council, who have jurisdiction over their territory.

“This pipeline does not go through one band” community, said John Ridsdale, a.k.a. Hereditary Chief Na’Moks, one of two hereditary chiefs of the Tsayu or Beaver Clan.

The Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that in order for resource projects to go ahead on Indigenous lands, the government must engage in consultation with Indigenous communities in order to receive their “free, prior and informed consent” for the project.

But Chief Na’Moks says the B.C. government abdicated its responsibility for consultation to a corporation, in this case Coastal GasLink. And when the hereditary chiefs pushed back, the government sent in the RCMP.

“You look at ‘free, prior and informed consent,’ and at this point now, looking down the barrel of a gun, I don’t know how that can be considered ‘free,’” he said.

There has been a Wet’suwet’en checkpoint on the Morice West Forest Service Road, erected at Unist’ot’en Village on Dark House territory, since 2009. In 2018, Coastal GasLink filed an injunction against the checkpoint, alleging its workers were unable to enter the territory to begin construction on the man camp.

In December 2018, the B.C. Supreme Court granted a temporary injunction, but the Wet’suwet’en refused to allow Coastal GasLink to cross. The following month the RCMP raided the checkpoint, arresting 14 people.

Eventually the chiefs met with Coastal GasLink and agreed to let workers enter Wet’suwet’en territory to conduct “soft work” like water and soil sample collection and testing. But Chief Na’Moks told The Tyee in a recent phone interview that Coastal GasLink did not stick to the rules.

“They started clearing trees, building roads, put in a man camp. They absolutely abused the access, which we had allowed,” he said.

“We had filed a judicial review of the certification and permitting of Coastal GasLink — it’s before the Oil and Gas Commission right now — and in a 10-month period we have in excess of 50 infractions.”

All nine existing hereditary chiefs oppose the project, and issued an eviction notice to Coastal GasLink workers on Jan. 4, 2020. By this point three protest camps had been established along the service road to stop Coastal GasLink workers from entering.

But the granting of the temporary injunction was enough to grant the RCMP powers to raid the camps. After weeks of tense standoff, the RCMP began moving in, and over the course of a week beginning Feb. 6 they raided and dismantled three Wet’suwet’en camps along the Morice West Forest Service Road, arresting almost 30 people. No charges have been laid.

3. PREVIOUS COURT RULINGS

While the continued existence and relevance of Indigenous land-based legal systems may come as news to many Canadians, it is not news to our governments or law courts.

In fact, it is recognized in our Constitution: Sec. 35 recognizes and affirms the “existing Aboriginal and treaty rights.”

And our Charter of Rights and Freedoms: the rights and freedoms of others do not override or take away those of Indigenous people.

Over the past 30 years there have been several provincial and national court rulings affirming the existence and continued relevance of Indigenous legal systems in what is now known as Canada. In the interest of time and space, here are just a few:

R. v. Van der Peet (SCC 1996): Dorothy Marie Van der Peet, a member of the Stó:lō Nation, was charged with selling fish without a license. Van der Peet maintained this infringed on her Indigenous hunting and fishing rights as outlined under Sec. 35 of the constitution.

While Van der Peet lost the case, Supreme Court of Canada judge Beverley McLachlin wrote:

“The history of the interface of Europeans and the common law with aboriginal peoples is a long one. As might be expected of such a long history, the principles by which the interface has been governed have not always been consistently applied. Yet running through this history, from its earliest beginnings to the present time is a golden thread — the recognition by the common law of the ancestral laws and customs of the aboriginal peoples who occupied the land prior to European settlement.”

Delgamuukw vs. The Queen/British Columbia (SCC 1997): A combined legal effort by the 13 Wet’suwet’en and 35 Gitxsan hereditary chiefs to stop the province of B.C. from clearcutting on their unceded territories. Originally filed in 1984, it took 13 years to reach the Supreme Court of Canada, who ruled they could not establish Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan rights and title due to a technicality. Instead they suggested a retrial, or negotiations with the province and federal governments.

With their resources exhausted, neither Nation brought the case to trial again, and negotiations with Canadian and provincial governments did not happen.

However, Delgamuukw, named after just one of the hereditary chiefs involved, did rule that Indigenous oral history, previously dismissed by lower courts as irrelevant, was just as valid as European settlers’ written histories. And it maintained Indigenous rights and title could not be dismissed or dissolved by Canadian or provincial governments.

The Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia (SCC, 2014): This was the first Supreme Court of Canada case to rule definitively on Indigenous rights and title. The courts granted the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s claim to the 1,750 square kilometres they were in court to protect from clear-cut logging.

While the courts did not say the decision over resource extraction in the region belonged to the Tsilhqot’in Nation alone, it did rule colonial governments must engage in consultations with First Nations, government-to-government, for free, prior and informed consent on resource projects happening on their land before greenlighting a project.

As Judith Sayers, a.k.a. Kekinusuqs from Hupacasath First Nation in Port Alberni, B.C., president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, wrote in The Tyee a month after the ruling was released, “My prediction was that this country would be rocked by the Tsilhqot’in decision and it certainly was. We are still feeling the reverberations from the Tsilhqot’in decision and will for many years to come.”

(You can read about other relevant court cases here and here.)

4. PAST STANDOFFS AND THE SHIFTING LEGAL CONTEXT

The Wet’suwet’en blockades are not the first time First Nations people have literally stood their ground on land and title disputes in Canada.

This summer marks the 30th anniversary of the Oka Crisis, a 78-day standoff between the Mohawk and the province of Quebec over the expansion of a nine-hole golf course by the Oka municipality onto sacred Kanesatake Mohawk territory. While no golf course was built, the Mohawk continue to fight off development on the territory.

And 25 years ago, 400 police officers and the army came down on 20 Ts’peten Defenders of the Secwepemc Nation at Gustafsen Lake, B.C., after a 31-day standoff over ranchers’ grazing rights on Secwepemc land.

But this is the first land standoff since the Supreme Court of Canada made clear that Indigenous law was never extinguished, said Kate Gunn, a lawyer with First Peoples Law.

Gunn’s firm is representing the Dark House in an upcoming judicial review of Coastal GasLink’s archeological mitigation plan for their territory. Gunn spoke to The Tyee on her own behalf, not that of the Dark House.

The courts have ruled governments, not corporations, must engage in nation-to-nation consultations, Gunn said, that is consistent with the Indigenous nation’s laws and cultural practices in seeking free, prior and informed consent.

“I don’t think that the federal or provincial governments, at this point, have really grappled with what that means in terms of having the Wet’suwet’en or other Indigenous groups really actively asserting their laws and jurisdiction out on the land,” she said.

“There isn’t a template that says which law is paramount when that happens.”

5. UNDRIP

Then there is the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, more commonly referred to as UNDRIP, a non-binding resolution outlining the rights of Indigenous people worldwide. Passed by the United Nations in 2007, Canada did not endorse the declaration until 2010, although it still referred to the document as “aspirational.”

It would be late 2015 before the federal government promised to adopt and implement the declaration, a move we are still waiting on over four years later. Rather, it was British Columbia who took the first step last October by becoming the only province to pass legislation aimed at implementing the declaration in all provincial ministries, Crown corporations and laws.

The celebrations didn’t last long. RCMP raids on Wet’suwet’en territory, according to some who occupied the steps of the B.C. legislature last week, appear to directly violate at least one of UNDRIP’s 46 articles. They point to Article 8 which declares, “States shall provide effective mechanisms for prevention of, and redress” for any action “which has the aim or effect of dispossessing them of their lands, territories or resources” and any “form of forced population transfer which has the aim or effect of violating or undermining any of their rights.”

Sayers, who is also an assistant professor of business and law at the University of Victoria, highlighted in The Tyee a few other UNDRIP articles these raids may violate:

“For instance, Article 18 gives the Wet’suwet’en the right to participate in any decision-making through their own procedures and law. This has not happened. Article 26 gives them the right to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources they possess through ownership, and says the state must give legal recognition and protect their lands and resources. None of this has occurred to date, and it doesn’t look like B.C. is even considering it. The government is saying this is Crown land, the company has Crown permits, so therefore the development must happen.”

6. WHAT’S NEXT FOR THE COURTS

In her New Year’s Eve decision granting the injunction that triggered last week’s RCMP raids, Madam Justice Church of the B.C. Court of Appeal made several statements regarding whether Wet’suwet’en law should be factored when land claims remain unsettled.

“As a general rule, Indigenous customary laws do not become an effectual part of Canadian common law or Canadian domestic law until there is some means or process by which the Indigenous customary law is recognized as being part of Canadian domestic law, either through incorporation into treaties, court declarations, such as Aboriginal title or rights jurisprudence or statutory provisions,” she wrote.

“There has been no process by which Wet’suwet’en customary laws have been recognized in this manner. The Aboriginal title claims of the Wet’suwet’en people have yet to be resolved either by negotiation or litigation. While Wet’suwet’en customary laws clearly exist on their own independent footing, they are not recognized as being an effectual part of Canadian law.”

Ultimately Church concluded the issue of whether Wet’suwet’en law and land title were legitimate are beyond the scope of an injunction hearing. “This is not the venue for that analysis and those are issues that must be determined at trial.”

Gavin Smith, a staff lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law and Smithers resident, wrote a blog post tackling Madam Justice Church’s conclusions.

Riveting Video Captures RCMP Raid of Gidimt’en Camp READ MORE

He notes: “The recognition of Indigenous governance within the Canadian legal system is emphatically not an issue specific to Dark House or the Wet’suwet’en. We all have an interest in the recognition of Indigenous governance, both to address colonial injustices and to uphold the law in its fullest sense (including the Canadian constitution).”

In the wake of the injunctions, members of the Wet’suwet’en Nation have launched several court actions including a judicial review of Coastal GasLink’s permit as it relates to man camps and their documented impact on violence against women and girls; and a constitutional challenge over the potential environmental impacts of a liquid natural gas pipeline and the resulting carbon emissions.

This fight is far from over, but the existing Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs express confidence their law will prevail.

“At one point they said, ‘You’ve got to prove your strength of claim,’” Na’Moks said of the B.C. government. “I’d like to see their strength of claim. We know ours. We’ve been here for thousands of years.”

Read more: Indigenous Affairs, Rights + Justice

Unlike the majority of Canada, most of the territory we now know as British Columbia was never ceded by First Nations who have lived on these lands for at least the last 14,000 years.

In contrast, the Colony of British Columbia, as settlers first called the province, has existed for just over 160 years — less than one per cent of the time First Nations people have lived here.

Except for the Douglas Treaties on Vancouver Island, a portion of northeastern B.C. covered by Treaty 8, and a handful of modern treaties signed since the 1990s, the majority of British Columbia is First Nations’ land that was never covered by a treaty or taken as spoils of war.

Today, there are 200 distinct First Nations occupying their territories in B.C.

Like their lives and cultures, First Nations and Inuit legal systems across Canada were never extinguished, even where treaties were signed. The Supreme Court of Canada has declared these legal systems, unique to each nation, never stopped being valid just because Europeans settled here.

The Tyee is supported by readers like you Join us and grow independent media in Canada

This reality has meant continual clashes between Canadian governments who wish to mine natural resources for profit and jobs, and Indigenous people asserting their right to a seat at the table where decisions are made over how lands and resources are used.

The latest such conflict occurred last week when the Royal Canadian Mounted Police entered the unceded territory of the Wet’suwet’en Nation, 22,000 square kilometres located southwest of Smithers, arresting almost 30 Wet’suwet’en people and their allies.

The police were enforcing a Dec. 31, 2019 B.C. Court of Appeal injunction granted on behalf of Coastal GasLink, a subsidiary of TC Energy, a.k.a. TransCanada Energy.

Last month, following the injunction ruling, B.C. Premier John Horgan announced the Coastal GasLink project would go ahead, telling the media “the rule of law applies” now that the courts had sided with TC Energy.

But on unceded territory, the title of which is claimed by a First Nation living there for thousands of years without signed treaties or surrendering their land, whose rule of law applies? That question drives intensifying debate and protests.

Let’s break down and clarify six elements at play in this legal drama.

1. THE INJUNCTION

The B.C. Supreme Court’s Dec. 31 injunction sided with Coastal GasLink, giving it the right to continue construction on a 400-person “man camp” in anticipation of a provincial permit to construct a liquefied natural gas (LNG) pipeline running from Dawson’s Creek to Kitimat, B.C.

Both the man camp and the pipeline will cut right through untouched Wet’suwet’en territory.

This series of raids is the second time in 13 months the RCMP had raided Wet’suwet’en checkpoints along the logging road leading to the proposed man camp site. The previous raids were in the wake of a temporary injunction granted Coastal GasLink. In both cases arrests were made in the name of Coastal GasLink workers’ safe access to the territory.

Injunctions have proven an effective legal tool in Canada for corporations. The Yellowhead Institute, a First Nations-led research centre focusing on land and governance based in Ryerson University’s faculty of arts, released a report last fall showing of the roughly 100 injunctions they reviewed, 76 per cent filed by corporations against First Nations were granted, but just 19 per cent of injunctions filed by First Nations against corporations were approved.

“Land alienation is linked to the broader political economy of Canada that relies to a significant extent on its natural resource sector to secure jobs and investment. Thus, land alienation is a major economic driver of the Canadian economy,” the report concludes.

2. HEREDITARY CHIEFS AND BAND COUNCILS

Under the Indian Act, those who are recognized by the federal government as having First Nations “status” are grouped into bands, led by a chief and council elected by the band members.

Bands have control over reserve lands, where First Nations were forcibly relocated — sometimes on their own territories, sometimes not — under the Indian Act. Under Canadian law, reserve lands actually belong to the Crown, but bands have jurisdiction over the people and services on those reserves.

Coastal GasLink has signed Impact and Benefit Agreements with 20 Indian Act band councils along the 670-kilometre proposed pipeline route.

Prior to the passing of the Indian Act in 1876, First Nations, including the Wet’suwet’en had their own leadership and legal systems that were ignored by colonial governments, but never extinguished.

While the elected Wet’suwet’en chief and council have jurisdiction over the reserve communities on their territory, the rest of the 22,000 square kilometre territory — roughly the size of New Jersey — is the jurisdiction of the 13 hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en Nation’s five clans: Gilseyhu, Likhts’amisyu, Laksilyu, Tsayu and Gidimt’en.

Between the five clans there are 13 houses, each with their own territory overseen by a hereditary chief. The proposed Coastal GasLink pipeline and man camp are slated for a section of Wet’suwet’en Nation controlled by the Dark House.

Due to the recent passing of two hereditary chiefs — and two hereditary chief vacancies — only nine of the 13 Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief positions are currently filled.

Unlike the hereditary royalty of the British monarchy, Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief is not a lifetime position bestowed on a bloodline. Rather, it’s a title that can be bequeathed a Wet’suwet’en Nation member based on their character and conduct — though this remains a matter of some dispute within the Wet’suwet’en First Nation.

While the elected Wet’suwet’en band council signed an agreement in favour of the pipeline with Coastal GasLink, the nine Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs maintain it is they, not the band council, who have jurisdiction over their territory.

“This pipeline does not go through one band” community, said John Ridsdale, a.k.a. Hereditary Chief Na’Moks, one of two hereditary chiefs of the Tsayu or Beaver Clan.

The Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that in order for resource projects to go ahead on Indigenous lands, the government must engage in consultation with Indigenous communities in order to receive their “free, prior and informed consent” for the project.

But Chief Na’Moks says the B.C. government abdicated its responsibility for consultation to a corporation, in this case Coastal GasLink. And when the hereditary chiefs pushed back, the government sent in the RCMP.

“You look at ‘free, prior and informed consent,’ and at this point now, looking down the barrel of a gun, I don’t know how that can be considered ‘free,’” he said.

There has been a Wet’suwet’en checkpoint on the Morice West Forest Service Road, erected at Unist’ot’en Village on Dark House territory, since 2009. In 2018, Coastal GasLink filed an injunction against the checkpoint, alleging its workers were unable to enter the territory to begin construction on the man camp.

In December 2018, the B.C. Supreme Court granted a temporary injunction, but the Wet’suwet’en refused to allow Coastal GasLink to cross. The following month the RCMP raided the checkpoint, arresting 14 people.

Eventually the chiefs met with Coastal GasLink and agreed to let workers enter Wet’suwet’en territory to conduct “soft work” like water and soil sample collection and testing. But Chief Na’Moks told The Tyee in a recent phone interview that Coastal GasLink did not stick to the rules.

“They started clearing trees, building roads, put in a man camp. They absolutely abused the access, which we had allowed,” he said.

“We had filed a judicial review of the certification and permitting of Coastal GasLink — it’s before the Oil and Gas Commission right now — and in a 10-month period we have in excess of 50 infractions.”

All nine existing hereditary chiefs oppose the project, and issued an eviction notice to Coastal GasLink workers on Jan. 4, 2020. By this point three protest camps had been established along the service road to stop Coastal GasLink workers from entering.

But the granting of the temporary injunction was enough to grant the RCMP powers to raid the camps. After weeks of tense standoff, the RCMP began moving in, and over the course of a week beginning Feb. 6 they raided and dismantled three Wet’suwet’en camps along the Morice West Forest Service Road, arresting almost 30 people. No charges have been laid.

3. PREVIOUS COURT RULINGS

While the continued existence and relevance of Indigenous land-based legal systems may come as news to many Canadians, it is not news to our governments or law courts.

In fact, it is recognized in our Constitution: Sec. 35 recognizes and affirms the “existing Aboriginal and treaty rights.”

And our Charter of Rights and Freedoms: the rights and freedoms of others do not override or take away those of Indigenous people.

Over the past 30 years there have been several provincial and national court rulings affirming the existence and continued relevance of Indigenous legal systems in what is now known as Canada. In the interest of time and space, here are just a few:

R. v. Van der Peet (SCC 1996): Dorothy Marie Van der Peet, a member of the Stó:lō Nation, was charged with selling fish without a license. Van der Peet maintained this infringed on her Indigenous hunting and fishing rights as outlined under Sec. 35 of the constitution.

While Van der Peet lost the case, Supreme Court of Canada judge Beverley McLachlin wrote:

“The history of the interface of Europeans and the common law with aboriginal peoples is a long one. As might be expected of such a long history, the principles by which the interface has been governed have not always been consistently applied. Yet running through this history, from its earliest beginnings to the present time is a golden thread — the recognition by the common law of the ancestral laws and customs of the aboriginal peoples who occupied the land prior to European settlement.”

Delgamuukw vs. The Queen/British Columbia (SCC 1997): A combined legal effort by the 13 Wet’suwet’en and 35 Gitxsan hereditary chiefs to stop the province of B.C. from clearcutting on their unceded territories. Originally filed in 1984, it took 13 years to reach the Supreme Court of Canada, who ruled they could not establish Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan rights and title due to a technicality. Instead they suggested a retrial, or negotiations with the province and federal governments.

With their resources exhausted, neither Nation brought the case to trial again, and negotiations with Canadian and provincial governments did not happen.

However, Delgamuukw, named after just one of the hereditary chiefs involved, did rule that Indigenous oral history, previously dismissed by lower courts as irrelevant, was just as valid as European settlers’ written histories. And it maintained Indigenous rights and title could not be dismissed or dissolved by Canadian or provincial governments.

The Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia (SCC, 2014): This was the first Supreme Court of Canada case to rule definitively on Indigenous rights and title. The courts granted the Tsilhqot’in Nation’s claim to the 1,750 square kilometres they were in court to protect from clear-cut logging.

While the courts did not say the decision over resource extraction in the region belonged to the Tsilhqot’in Nation alone, it did rule colonial governments must engage in consultations with First Nations, government-to-government, for free, prior and informed consent on resource projects happening on their land before greenlighting a project.

As Judith Sayers, a.k.a. Kekinusuqs from Hupacasath First Nation in Port Alberni, B.C., president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, wrote in The Tyee a month after the ruling was released, “My prediction was that this country would be rocked by the Tsilhqot’in decision and it certainly was. We are still feeling the reverberations from the Tsilhqot’in decision and will for many years to come.”

(You can read about other relevant court cases here and here.)

4. PAST STANDOFFS AND THE SHIFTING LEGAL CONTEXT

The Wet’suwet’en blockades are not the first time First Nations people have literally stood their ground on land and title disputes in Canada.

This summer marks the 30th anniversary of the Oka Crisis, a 78-day standoff between the Mohawk and the province of Quebec over the expansion of a nine-hole golf course by the Oka municipality onto sacred Kanesatake Mohawk territory. While no golf course was built, the Mohawk continue to fight off development on the territory.

And 25 years ago, 400 police officers and the army came down on 20 Ts’peten Defenders of the Secwepemc Nation at Gustafsen Lake, B.C., after a 31-day standoff over ranchers’ grazing rights on Secwepemc land.

But this is the first land standoff since the Supreme Court of Canada made clear that Indigenous law was never extinguished, said Kate Gunn, a lawyer with First Peoples Law.

Gunn’s firm is representing the Dark House in an upcoming judicial review of Coastal GasLink’s archeological mitigation plan for their territory. Gunn spoke to The Tyee on her own behalf, not that of the Dark House.

The courts have ruled governments, not corporations, must engage in nation-to-nation consultations, Gunn said, that is consistent with the Indigenous nation’s laws and cultural practices in seeking free, prior and informed consent.

“I don’t think that the federal or provincial governments, at this point, have really grappled with what that means in terms of having the Wet’suwet’en or other Indigenous groups really actively asserting their laws and jurisdiction out on the land,” she said.

“There isn’t a template that says which law is paramount when that happens.”

5. UNDRIP

Then there is the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, more commonly referred to as UNDRIP, a non-binding resolution outlining the rights of Indigenous people worldwide. Passed by the United Nations in 2007, Canada did not endorse the declaration until 2010, although it still referred to the document as “aspirational.”

It would be late 2015 before the federal government promised to adopt and implement the declaration, a move we are still waiting on over four years later. Rather, it was British Columbia who took the first step last October by becoming the only province to pass legislation aimed at implementing the declaration in all provincial ministries, Crown corporations and laws.

The celebrations didn’t last long. RCMP raids on Wet’suwet’en territory, according to some who occupied the steps of the B.C. legislature last week, appear to directly violate at least one of UNDRIP’s 46 articles. They point to Article 8 which declares, “States shall provide effective mechanisms for prevention of, and redress” for any action “which has the aim or effect of dispossessing them of their lands, territories or resources” and any “form of forced population transfer which has the aim or effect of violating or undermining any of their rights.”

Sayers, who is also an assistant professor of business and law at the University of Victoria, highlighted in The Tyee a few other UNDRIP articles these raids may violate:

“For instance, Article 18 gives the Wet’suwet’en the right to participate in any decision-making through their own procedures and law. This has not happened. Article 26 gives them the right to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources they possess through ownership, and says the state must give legal recognition and protect their lands and resources. None of this has occurred to date, and it doesn’t look like B.C. is even considering it. The government is saying this is Crown land, the company has Crown permits, so therefore the development must happen.”

6. WHAT’S NEXT FOR THE COURTS

In her New Year’s Eve decision granting the injunction that triggered last week’s RCMP raids, Madam Justice Church of the B.C. Court of Appeal made several statements regarding whether Wet’suwet’en law should be factored when land claims remain unsettled.

“As a general rule, Indigenous customary laws do not become an effectual part of Canadian common law or Canadian domestic law until there is some means or process by which the Indigenous customary law is recognized as being part of Canadian domestic law, either through incorporation into treaties, court declarations, such as Aboriginal title or rights jurisprudence or statutory provisions,” she wrote.

“There has been no process by which Wet’suwet’en customary laws have been recognized in this manner. The Aboriginal title claims of the Wet’suwet’en people have yet to be resolved either by negotiation or litigation. While Wet’suwet’en customary laws clearly exist on their own independent footing, they are not recognized as being an effectual part of Canadian law.”

Ultimately Church concluded the issue of whether Wet’suwet’en law and land title were legitimate are beyond the scope of an injunction hearing. “This is not the venue for that analysis and those are issues that must be determined at trial.”

Gavin Smith, a staff lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law and Smithers resident, wrote a blog post tackling Madam Justice Church’s conclusions.

Riveting Video Captures RCMP Raid of Gidimt’en Camp READ MORE

He notes: “The recognition of Indigenous governance within the Canadian legal system is emphatically not an issue specific to Dark House or the Wet’suwet’en. We all have an interest in the recognition of Indigenous governance, both to address colonial injustices and to uphold the law in its fullest sense (including the Canadian constitution).”

In the wake of the injunctions, members of the Wet’suwet’en Nation have launched several court actions including a judicial review of Coastal GasLink’s permit as it relates to man camps and their documented impact on violence against women and girls; and a constitutional challenge over the potential environmental impacts of a liquid natural gas pipeline and the resulting carbon emissions.

This fight is far from over, but the existing Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs express confidence their law will prevail.

“At one point they said, ‘You’ve got to prove your strength of claim,’” Na’Moks said of the B.C. government. “I’d like to see their strength of claim. We know ours. We’ve been here for thousands of years.”

Read more: Indigenous Affairs, Rights + Justice

No comments:

Post a Comment