Leftist theologian Adam Kotsko on the Trump coup, the collapse of neoliberalism and the apocalypse overdose

By PAUL ROSENBERG FEBRUARY 6, 2021

POSTMODERN MANACHISM

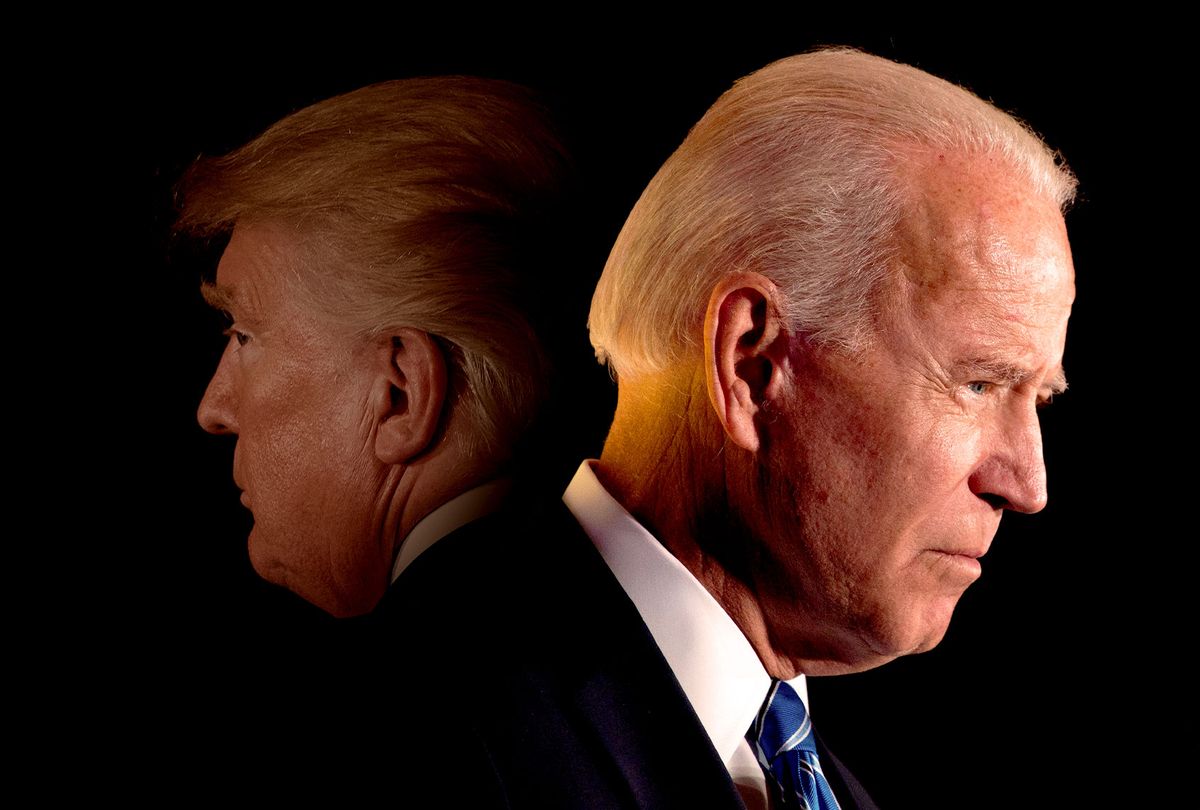

Joe Biden and Donald Trump (Photo illustration by Salon/Getty Images)

In the wake of Donald Trump's failed insurrection, the most reflective observation I have encountered is theologian Adam Kotsko's article "An Apocalypse About Nothing," in a new left-wing Christian publication called The Bias. (That confusing name apparently has a heritage in the 1960s British Catholic left.) While the 24/7 cable news narrative has been all about how dramatically different the Trump and Biden presidencies are, Kotsko stressed the opposite: Trump's child separation policy was virtually the only thing to set him apart from previous Republican presidents, while "Joe Biden is the most conservative Democratic nominee of the postwar era."

While many people might argue with those assessments, it's more difficult to dispute Kotsko's deeper point about the broader historical pattern: "Over and [over] again, and to an increasing degree, the alternation of power between two broadly similar political parties is treated as an apocalyptic emergency." When every election is the most catastrophically important in history — when nothing is ever gained, beyond a temporary reprieve — something is surely missing at the core.

Kotsko also noted that "the word 'apocalypse' refers etymologically to a revelation, or more literally an uncovering," adding: "Apocalyptic literature always finds its society and historical moment to be corrupt and decadent." So rather than rail against the overheated apocalyptic rhetoric of others, Kotsko undertook his own cool-eyed, analytical version, saying, "I will follow my prophetic and apostolic forebears in diagnosing the root cause of that corruption and decadence as a failure to recognize the truth, which has resulted in a thoroughgoing moral and political nihilism."

That truth is not simply the failure of the neoliberal order — ushered in by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, but embraced by Bill Clinton, Tony Blair and Barack Obama as well — but a good deal more as well: the lies about human nature, freedom and the market which lie at the core of the neoliberal faith, as Kotsko unfolded in his 2018 book, "Neoliberalism's Demons: On the Political Theology of Late Capital." So I reached out to ask him to discuss what he had uncovered at the core of our historical moment's "corruption and decadence." This interview has been edited, as usual, for clarity and length.

Shortly after Trump's failed coup attempt, you wrote "An Apocalypse About Nothing." You called the attempt "a potentially apocalyptic moment, one in which all our certainties about constitutional government and electoral politics dissolved and all bets were off," and yet in terms of normal politics, you argue, it was hard to see why. Above the blow-by-blow melodrama, from a larger perspective many people would agree that the Democrats lack the confidence and vision to stand up to Republicans, and I think your work can help us better understand why. But I want to begin with your deeper argument. You write that in your book you argue that neoliberalism "has always been an apocalyptic discourse."

In the wake of Donald Trump's failed insurrection, the most reflective observation I have encountered is theologian Adam Kotsko's article "An Apocalypse About Nothing," in a new left-wing Christian publication called The Bias. (That confusing name apparently has a heritage in the 1960s British Catholic left.) While the 24/7 cable news narrative has been all about how dramatically different the Trump and Biden presidencies are, Kotsko stressed the opposite: Trump's child separation policy was virtually the only thing to set him apart from previous Republican presidents, while "Joe Biden is the most conservative Democratic nominee of the postwar era."

While many people might argue with those assessments, it's more difficult to dispute Kotsko's deeper point about the broader historical pattern: "Over and [over] again, and to an increasing degree, the alternation of power between two broadly similar political parties is treated as an apocalyptic emergency." When every election is the most catastrophically important in history — when nothing is ever gained, beyond a temporary reprieve — something is surely missing at the core.

Kotsko also noted that "the word 'apocalypse' refers etymologically to a revelation, or more literally an uncovering," adding: "Apocalyptic literature always finds its society and historical moment to be corrupt and decadent." So rather than rail against the overheated apocalyptic rhetoric of others, Kotsko undertook his own cool-eyed, analytical version, saying, "I will follow my prophetic and apostolic forebears in diagnosing the root cause of that corruption and decadence as a failure to recognize the truth, which has resulted in a thoroughgoing moral and political nihilism."

That truth is not simply the failure of the neoliberal order — ushered in by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, but embraced by Bill Clinton, Tony Blair and Barack Obama as well — but a good deal more as well: the lies about human nature, freedom and the market which lie at the core of the neoliberal faith, as Kotsko unfolded in his 2018 book, "Neoliberalism's Demons: On the Political Theology of Late Capital." So I reached out to ask him to discuss what he had uncovered at the core of our historical moment's "corruption and decadence." This interview has been edited, as usual, for clarity and length.

Shortly after Trump's failed coup attempt, you wrote "An Apocalypse About Nothing." You called the attempt "a potentially apocalyptic moment, one in which all our certainties about constitutional government and electoral politics dissolved and all bets were off," and yet in terms of normal politics, you argue, it was hard to see why. Above the blow-by-blow melodrama, from a larger perspective many people would agree that the Democrats lack the confidence and vision to stand up to Republicans, and I think your work can help us better understand why. But I want to begin with your deeper argument. You write that in your book you argue that neoliberalism "has always been an apocalyptic discourse."

First of all, how do you define neoliberalism?

Advertisement:

Chris Wallace and Fox News journalists can never win at the pro-Trump network

Advertisement:

Chris Wallace and Fox News journalists can never win at the pro-Trump network

00:00/01:59 Go To Video Page

Neoliberalism is the political and economic project which has been a shared ambition by most major parties in most Western countries for the last generation. It is a project of trying to reimagine and re-create as many parts of society as possible on the model of a competitive market.

What do you mean by describing it as an "apocalyptic discourse"?

It started off as an oppositional movement. Especially after the First World War and the Great Depression, the free market ideal was under threat. It had been discredited and different alternatives were being tried, including more radical alternatives like the Soviet Union. So the people who were theorizing this before it became public policy were constantly like, "You need to adopt our free-market ideals or else you're going to be Communists." So it was like a voice calling in the wilderness: "Get back to the gospel of the free-market or else you're going to lose your freedom forever!"

When Reagan came in, and Thatcher as well, they adopted a similar kind of apocalyptic tone, except that they were kind of like the messiah implementing this plan. It was defeating all these enemies. Reagan is often credited — probably falsely — with delivering the crushing blow against the Soviet Union that made its dissolution inevitable and breaking the welfare state, all these powers that were literally demonized in a lot of neoliberal discourse The perception was that he was the one vanquishing them.

Then when the Democrats adopted the discourse themselves, how was it apocalyptic for them?

I think for them it turned around the idea that once the neoliberal order was established, it was no longer a matter of defeating these alternatives, because they had been all defeated. You know, the claim that there was no alternative to neoliberalism seemed true at that moment. The only threats were just these nihilistic threats of disaster — natural disasters, chaos, failed states, terrorism — these purely negative threats that were constantly menacing the world scene. The Democrats, and basically the left wing of neoliberalism in general, positioned themselves as trying to stabilize and rationalize the neoliberal system so that these nihilistic threats would not fester and lash out.

In your book, "Neoliberalism's Demons," you write that "neoliberalism makes demons of us all." Can you explain what's entailed in this demonization? It's a bit different from what folks might think.

I think the common use of the word "demonization" — aside from literally making an analogy between somebody and a demon — suggests saying something like really, really negative about them. Like, Republicans hate Hillary Clinton, so they demonized her. But I think there's a little bit more nuance to that, if you look at the theological tradition and what Christian thinkers were saying about how demons came about.

According to this mythology, God created them initially as angels, but then gave them this kind of impossible test, from the very first moment that they were created. Some of them were deemed to have failed for choosing not to submit to God quickly enough, or something like that. I took that to be emblematic of something that happens constantly in neoliberalism, which is that we're given a kind of false or meaningless choice that just sets us up to fail. That just puts us in a position where we are supposedly responsible for the bad outcome but doesn't give us enough power to actually change the situation, or change the terms of the choice we're given.

Your book talks about student debt in relationship to that. Could you say something more about that, to help flesh it out?

I think especially with talk of student loan forgiveness coming up, this is an especially relevant example. When people are arguing against student debt forgiveness, they say it's unfair to those who were responsible, and either didn't take on debt or worked their way through college or they paid them off, and that you're going to create incentives for people to take on all these irresponsible debts that they can't pay for. In general, student debt us a great example of this entrapment, because on the one hand, it's a contract that's freely entered into, but on the other hand, students are constantly told from a very young age that the only way they're going to have a livable life is if they go to college.

So they feel trapped. They have to take on student loans, because the alternative of not going to college just doesn't seem viable to them. And then they're on the hook for this very unusual form of debt that you can't get out of through bankruptcy, that you have to pay for even if you didn't finish your degree. It's a situation that's basically set up so that they can only fail, that they can only hurt themselves. But on a formal level, they are still responsible because they freely chose to do it.

You go on to talk about the benefits that flow to the purveyors of neoliberalism, both Republicans and Democrats, from leaning into this apocalyptic tone. Say a bit more about that.

If you look at what neoliberalism is promising, it's kind of boring. There's not a lot of dynamism or meaning to it. It's just like, if we set up economic incentives in the right way, then the right people will be rewarded and the lazy people will be punished, or something like that. I think Thomas Frank once wrote an article where he called neoliberalism "The God That Sucked." [Note: Frank was referring to the market with that term, but by extension the ideology of neoliberalism was clearly implicated.]

I think this apocalyptic rhetoric really gives us a sense of meaning and moral heft that it doesn't objectively have. It's the paradox of somebody claiming, "I'm on this great moral crusade and opposing these powerful forces," when really they're saying we should let the rich get even richer. The apocalyptic stance helps to resolve some of this cognitive dissonance, and give people an emotional attachment to it that wouldn't otherwise exist.

There's also an awful lot of scolding that goes along with neoliberalism.

It is very moralistic, very intent on blaming people. I think that neoliberalism presents itself as being about individual freedom and that it's trying to set up society so that whatever happens is a reflection of all of us collectively — or at least that it aggregates all our decisions onto the outcome that we all want. Since individual choice is the only kind of choice it recognizes, politicians wind up kind of pulling that string a lot to offload responsibility on individuals rather than themselves.

I think we've seen this a lot with COVID, the pandemic. It's intrinsically a shared, collective thing that requires a large-scale response, and yet we're constantly asked to be angry at individuals who choose not to wear masks, when there isn't a law making them wear masks. Individuals are supposed to discern what the true guidance should be on safety and respond appropriately, even though the political authorities haven't actually given that to them. It's really been reduced to a pretty absurd point in the pandemic, but it shows a dynamic that's always been going on.

You write that "Over and [over] again, and to an increasing degree, the alternation of power between two broadly similar political parties is treated as an apocalyptic emergency." But then came what you call "the genuine neoliberal apocalypse," meaning the great financial crisis of 2008. Why was that an apocalypse specifically for the neoliberal worldview?

Because it objectively discredited all their claims about how society works and how the market works. For them, the market is supposed to take individual choices and produce the appropriate rewards or punishments. But given that the crisis was so widespread and universal, it's not as though everybody just stopped and decided to make the wrong choices. And especially the fact that the choice that was being punished was buying a house, which is normally seen as the mark of responsibility. That added a kind of absurdity, like adding insult to injury. It also exposed the fallacy that the market is supposed to be much wiser and more far-seeing than any human being could be, when in fact the market was so completely wrong about these subprime mortgages and had built so much on them. That seemed to discredit the ideas that the market can handle things. So I think, objectively speaking, this should have forced a reckoning: Man, maybe we've been wrong this whole time. And it did not.

That's just what I wanted to ask about next: Why didn't we get any kind of significant or meaningful change?

I think that, first of all, we shouldn't have expected any change from the Republicans. They just kind of doubled down on their scapegoating, and they fantasized that the crisis was due to individual bad actors, which just so happened to be minorities. For instance, with the fantasies that mortgage subsidies somehow caused it, or something like that. So they're just stuck in a complete fantasyland of trying to make the math work out.

I think that for Democrats, it was both fortunate and also very unfortunate that Obama arose at the moment that he did. Because it seems like he was kind of a unique political talent, and the only one who could sell this agenda. He was very dedicated to doing neoliberal best practices, and bringing everybody in who supposedly knew what they were doing. They applied those practices and the economy did start to get better, based on the metrics, even if people were suffering, and even though the unemployment rate was misleading because so many people had supposedly given up. It still seemed to be getting better. And he then won re-election too, which seemed to endorse the fact that the best practices had worked.

I think that on the one hand, the Republicans became completely detached from reality, and on the other hand, the Democrats became complacent, because they were treating very meager successes as, like, a vindication of their entire strategy. The real problem is that, given the neoliberal hold over both parties for so long, there's just been basically brain drain. There's nobody other than old-timers like Bernie Sanders who has any kind of different outlook. Anybody who's come up since the neoliberal turn has to be within that mindset, or else they can't get anywhere in the party. So when the time came, there was nobody to ask questions or to look at the situation differently.

You also identify the coronavirus crisis as the second time in this young century when "the neoliberal paradigm has faced an apocalyptic challenge." There's a greater divergence between Trump and Biden's responses than there was between Bush and Obama's, but you write that "the goal was still to ensure that the market continued to function 'normally,'" and you make the related observation that both parties "cannot afford to tell the truth ... that the neoliberal consensus has failed and will continue to fail."

This ties into the beginning of your piece, where you argue that Trump is not all that different from other Republicans, while Biden was the Democrats' most conservative postwar nominee. I see Biden as a weathervane candidate, who responded to a younger, more diverse electorate to get elected and has some desire to try new things, although perhaps there's a lack of sustaining ideas.

I've been pleasantly surprised by the directions Biden has taken, although my expectations were basically at rock-bottom. I think that what's lacking — the ideas are not lacking. I mean, if we're talking about basically reforming every aspect of society, plans exist, activist groups exist, academic studies of their plausibility exist. In terms of knowing what to do, we've got it. But all those solutions seem to be impossible. I think it's good that Biden is pushing for more relief, but that's still basically cutting checks to people. That's not restructuring the economy to make it more robust against the next inevitable pandemic. We know they're going to become more frequent. We know this is going to happen again, and simply giving people aid now does not restructure the economy so that it's more robust against something like that.

Most absurd of all, I think, is the rejection of Medicare for All. if there's ever been an event that shows that health is an intrinsically public good that he should be handled by society as a whole, not on a for-profit basis, surely it's this pandemic, yet that's still off the table. Biden has ruled all along that option is off the table, and has even said he would veto it. So I don't think it's a lack of ideas. I think it's just that so much is dismissed as impossible from the get-go, or as unrealistic, that it doesn't even get discussed. There is a difference, obviously an important difference, between the two parties. But on the grand scale of things, it's minuscule compared to what could be done and needs to be done.

What I meant by "ideas" was overarching, organizing ideas that can make sense of specific proposals and provide a shared framework on the scale of neoliberalism, ideas that are sweeping enough to provide a common orientation and set of shared assumptions people can draw on in a political discussion. That seems to be what we're lacking.

Yeah, that makes more sense. I think there is a kind of grab-bag quality to a lot of progressive proposals. That was something that the Green New Deal was castigated for, kind of wanting to do everything at once, but without a shared, easy core idea that's animates all of it and tells us why it's all connected. Have you seen this book by Mike Konczal, "Freedom From the Market"? It seems like that could be a promising step in the right direction. Trying to reclaim the term "freedom," instead of the market and freedom being identified. Making clear that we realize that the market is constraining in a lot of ways, and that it doesn't do certain things well, doesn't always have the right answers.

I think it helps to see the market as a human creation. Wheels are good things, but we get flat tires all the time. The maintenance of wheels and the maintenance of bridges are part of the package that comes with them. The same applies to markets: They're useful creations, but you don't worship them. You fix them to work properly.

I'm sure you're right there are good uses for markets, but it's the idolatry of markets that's the problem, the idea that everything has to be in that mold. Even right now, we're only talking about them negatively. We don't have a positive alternative. I think you're right, that's what's lacking. It's probably unrealistic to expect a man in his late 70s to suddenly have a come-to-Jesus moment and develop a whole new politics. [Laughter.]

We could perhaps stimulate those around him, and those coming up, to seek an alternative! Another thing I'm struck by is that idolatry of the market leads to a contraction of moral considerations: Rather than facing a multitude of moral goods that need to be considered distinctly, in different situations, everything is given a market price. It flattens out all moral reasoning. I think we need to push back against that, to revitalize our sense of diverse, pluralistic moral goods, as well as moral agency.

Yeah, I think you're right. Whenever we do that, we're always in this defensive crouch. There's always a temptation to turn the corner and say, "Actually, if we were more humane to each other, that would help the economy!" It tends to be this black hole that sucks everything out. In my own experience — I'm an academic in the humanities, and we always have to prove our worth somehow. Why can't we say, "Hey, business leaders, why don't we prove the worth of what you're doing? Why should you dominate our lives? Why should you control everything? The one chance we get for education in our lives — why should it be for you? Why can't it also be for us? Why can't it be for our own minds and our own interests?"

But it seems like everybody's more stuck on, like, "We provide critical thinking skills that will make you better at doing business!" That may be true or not true, but it's still within that framework. I think you're right that we lack that alternative. Even in my book, I wind up saying, "We need to abolish the market," but I don't say, "And here's what it will look like when we do it. Here's the positive alternative that will replace it." So I'm just as guilty as anybody.

I like to end my interviews by asking, "What's the most important question I didn't ask? And what's the answer?"

Where you can buy my book. [Laughter.]

PAUL ROSENBERG is a California-based writer/activist, senior editor for Random Lengths News, and a columnist for Al Jazeera English. Follow him on Twitter at @PaulHRosenberg.

Neoliberalism is the political and economic project which has been a shared ambition by most major parties in most Western countries for the last generation. It is a project of trying to reimagine and re-create as many parts of society as possible on the model of a competitive market.

What do you mean by describing it as an "apocalyptic discourse"?

It started off as an oppositional movement. Especially after the First World War and the Great Depression, the free market ideal was under threat. It had been discredited and different alternatives were being tried, including more radical alternatives like the Soviet Union. So the people who were theorizing this before it became public policy were constantly like, "You need to adopt our free-market ideals or else you're going to be Communists." So it was like a voice calling in the wilderness: "Get back to the gospel of the free-market or else you're going to lose your freedom forever!"

When Reagan came in, and Thatcher as well, they adopted a similar kind of apocalyptic tone, except that they were kind of like the messiah implementing this plan. It was defeating all these enemies. Reagan is often credited — probably falsely — with delivering the crushing blow against the Soviet Union that made its dissolution inevitable and breaking the welfare state, all these powers that were literally demonized in a lot of neoliberal discourse The perception was that he was the one vanquishing them.

Then when the Democrats adopted the discourse themselves, how was it apocalyptic for them?

I think for them it turned around the idea that once the neoliberal order was established, it was no longer a matter of defeating these alternatives, because they had been all defeated. You know, the claim that there was no alternative to neoliberalism seemed true at that moment. The only threats were just these nihilistic threats of disaster — natural disasters, chaos, failed states, terrorism — these purely negative threats that were constantly menacing the world scene. The Democrats, and basically the left wing of neoliberalism in general, positioned themselves as trying to stabilize and rationalize the neoliberal system so that these nihilistic threats would not fester and lash out.

In your book, "Neoliberalism's Demons," you write that "neoliberalism makes demons of us all." Can you explain what's entailed in this demonization? It's a bit different from what folks might think.

I think the common use of the word "demonization" — aside from literally making an analogy between somebody and a demon — suggests saying something like really, really negative about them. Like, Republicans hate Hillary Clinton, so they demonized her. But I think there's a little bit more nuance to that, if you look at the theological tradition and what Christian thinkers were saying about how demons came about.

According to this mythology, God created them initially as angels, but then gave them this kind of impossible test, from the very first moment that they were created. Some of them were deemed to have failed for choosing not to submit to God quickly enough, or something like that. I took that to be emblematic of something that happens constantly in neoliberalism, which is that we're given a kind of false or meaningless choice that just sets us up to fail. That just puts us in a position where we are supposedly responsible for the bad outcome but doesn't give us enough power to actually change the situation, or change the terms of the choice we're given.

Your book talks about student debt in relationship to that. Could you say something more about that, to help flesh it out?

I think especially with talk of student loan forgiveness coming up, this is an especially relevant example. When people are arguing against student debt forgiveness, they say it's unfair to those who were responsible, and either didn't take on debt or worked their way through college or they paid them off, and that you're going to create incentives for people to take on all these irresponsible debts that they can't pay for. In general, student debt us a great example of this entrapment, because on the one hand, it's a contract that's freely entered into, but on the other hand, students are constantly told from a very young age that the only way they're going to have a livable life is if they go to college.

So they feel trapped. They have to take on student loans, because the alternative of not going to college just doesn't seem viable to them. And then they're on the hook for this very unusual form of debt that you can't get out of through bankruptcy, that you have to pay for even if you didn't finish your degree. It's a situation that's basically set up so that they can only fail, that they can only hurt themselves. But on a formal level, they are still responsible because they freely chose to do it.

You go on to talk about the benefits that flow to the purveyors of neoliberalism, both Republicans and Democrats, from leaning into this apocalyptic tone. Say a bit more about that.

If you look at what neoliberalism is promising, it's kind of boring. There's not a lot of dynamism or meaning to it. It's just like, if we set up economic incentives in the right way, then the right people will be rewarded and the lazy people will be punished, or something like that. I think Thomas Frank once wrote an article where he called neoliberalism "The God That Sucked." [Note: Frank was referring to the market with that term, but by extension the ideology of neoliberalism was clearly implicated.]

I think this apocalyptic rhetoric really gives us a sense of meaning and moral heft that it doesn't objectively have. It's the paradox of somebody claiming, "I'm on this great moral crusade and opposing these powerful forces," when really they're saying we should let the rich get even richer. The apocalyptic stance helps to resolve some of this cognitive dissonance, and give people an emotional attachment to it that wouldn't otherwise exist.

There's also an awful lot of scolding that goes along with neoliberalism.

It is very moralistic, very intent on blaming people. I think that neoliberalism presents itself as being about individual freedom and that it's trying to set up society so that whatever happens is a reflection of all of us collectively — or at least that it aggregates all our decisions onto the outcome that we all want. Since individual choice is the only kind of choice it recognizes, politicians wind up kind of pulling that string a lot to offload responsibility on individuals rather than themselves.

I think we've seen this a lot with COVID, the pandemic. It's intrinsically a shared, collective thing that requires a large-scale response, and yet we're constantly asked to be angry at individuals who choose not to wear masks, when there isn't a law making them wear masks. Individuals are supposed to discern what the true guidance should be on safety and respond appropriately, even though the political authorities haven't actually given that to them. It's really been reduced to a pretty absurd point in the pandemic, but it shows a dynamic that's always been going on.

You write that "Over and [over] again, and to an increasing degree, the alternation of power between two broadly similar political parties is treated as an apocalyptic emergency." But then came what you call "the genuine neoliberal apocalypse," meaning the great financial crisis of 2008. Why was that an apocalypse specifically for the neoliberal worldview?

Because it objectively discredited all their claims about how society works and how the market works. For them, the market is supposed to take individual choices and produce the appropriate rewards or punishments. But given that the crisis was so widespread and universal, it's not as though everybody just stopped and decided to make the wrong choices. And especially the fact that the choice that was being punished was buying a house, which is normally seen as the mark of responsibility. That added a kind of absurdity, like adding insult to injury. It also exposed the fallacy that the market is supposed to be much wiser and more far-seeing than any human being could be, when in fact the market was so completely wrong about these subprime mortgages and had built so much on them. That seemed to discredit the ideas that the market can handle things. So I think, objectively speaking, this should have forced a reckoning: Man, maybe we've been wrong this whole time. And it did not.

That's just what I wanted to ask about next: Why didn't we get any kind of significant or meaningful change?

I think that, first of all, we shouldn't have expected any change from the Republicans. They just kind of doubled down on their scapegoating, and they fantasized that the crisis was due to individual bad actors, which just so happened to be minorities. For instance, with the fantasies that mortgage subsidies somehow caused it, or something like that. So they're just stuck in a complete fantasyland of trying to make the math work out.

I think that for Democrats, it was both fortunate and also very unfortunate that Obama arose at the moment that he did. Because it seems like he was kind of a unique political talent, and the only one who could sell this agenda. He was very dedicated to doing neoliberal best practices, and bringing everybody in who supposedly knew what they were doing. They applied those practices and the economy did start to get better, based on the metrics, even if people were suffering, and even though the unemployment rate was misleading because so many people had supposedly given up. It still seemed to be getting better. And he then won re-election too, which seemed to endorse the fact that the best practices had worked.

I think that on the one hand, the Republicans became completely detached from reality, and on the other hand, the Democrats became complacent, because they were treating very meager successes as, like, a vindication of their entire strategy. The real problem is that, given the neoliberal hold over both parties for so long, there's just been basically brain drain. There's nobody other than old-timers like Bernie Sanders who has any kind of different outlook. Anybody who's come up since the neoliberal turn has to be within that mindset, or else they can't get anywhere in the party. So when the time came, there was nobody to ask questions or to look at the situation differently.

You also identify the coronavirus crisis as the second time in this young century when "the neoliberal paradigm has faced an apocalyptic challenge." There's a greater divergence between Trump and Biden's responses than there was between Bush and Obama's, but you write that "the goal was still to ensure that the market continued to function 'normally,'" and you make the related observation that both parties "cannot afford to tell the truth ... that the neoliberal consensus has failed and will continue to fail."

This ties into the beginning of your piece, where you argue that Trump is not all that different from other Republicans, while Biden was the Democrats' most conservative postwar nominee. I see Biden as a weathervane candidate, who responded to a younger, more diverse electorate to get elected and has some desire to try new things, although perhaps there's a lack of sustaining ideas.

I've been pleasantly surprised by the directions Biden has taken, although my expectations were basically at rock-bottom. I think that what's lacking — the ideas are not lacking. I mean, if we're talking about basically reforming every aspect of society, plans exist, activist groups exist, academic studies of their plausibility exist. In terms of knowing what to do, we've got it. But all those solutions seem to be impossible. I think it's good that Biden is pushing for more relief, but that's still basically cutting checks to people. That's not restructuring the economy to make it more robust against the next inevitable pandemic. We know they're going to become more frequent. We know this is going to happen again, and simply giving people aid now does not restructure the economy so that it's more robust against something like that.

Most absurd of all, I think, is the rejection of Medicare for All. if there's ever been an event that shows that health is an intrinsically public good that he should be handled by society as a whole, not on a for-profit basis, surely it's this pandemic, yet that's still off the table. Biden has ruled all along that option is off the table, and has even said he would veto it. So I don't think it's a lack of ideas. I think it's just that so much is dismissed as impossible from the get-go, or as unrealistic, that it doesn't even get discussed. There is a difference, obviously an important difference, between the two parties. But on the grand scale of things, it's minuscule compared to what could be done and needs to be done.

What I meant by "ideas" was overarching, organizing ideas that can make sense of specific proposals and provide a shared framework on the scale of neoliberalism, ideas that are sweeping enough to provide a common orientation and set of shared assumptions people can draw on in a political discussion. That seems to be what we're lacking.

Yeah, that makes more sense. I think there is a kind of grab-bag quality to a lot of progressive proposals. That was something that the Green New Deal was castigated for, kind of wanting to do everything at once, but without a shared, easy core idea that's animates all of it and tells us why it's all connected. Have you seen this book by Mike Konczal, "Freedom From the Market"? It seems like that could be a promising step in the right direction. Trying to reclaim the term "freedom," instead of the market and freedom being identified. Making clear that we realize that the market is constraining in a lot of ways, and that it doesn't do certain things well, doesn't always have the right answers.

I think it helps to see the market as a human creation. Wheels are good things, but we get flat tires all the time. The maintenance of wheels and the maintenance of bridges are part of the package that comes with them. The same applies to markets: They're useful creations, but you don't worship them. You fix them to work properly.

I'm sure you're right there are good uses for markets, but it's the idolatry of markets that's the problem, the idea that everything has to be in that mold. Even right now, we're only talking about them negatively. We don't have a positive alternative. I think you're right, that's what's lacking. It's probably unrealistic to expect a man in his late 70s to suddenly have a come-to-Jesus moment and develop a whole new politics. [Laughter.]

We could perhaps stimulate those around him, and those coming up, to seek an alternative! Another thing I'm struck by is that idolatry of the market leads to a contraction of moral considerations: Rather than facing a multitude of moral goods that need to be considered distinctly, in different situations, everything is given a market price. It flattens out all moral reasoning. I think we need to push back against that, to revitalize our sense of diverse, pluralistic moral goods, as well as moral agency.

Yeah, I think you're right. Whenever we do that, we're always in this defensive crouch. There's always a temptation to turn the corner and say, "Actually, if we were more humane to each other, that would help the economy!" It tends to be this black hole that sucks everything out. In my own experience — I'm an academic in the humanities, and we always have to prove our worth somehow. Why can't we say, "Hey, business leaders, why don't we prove the worth of what you're doing? Why should you dominate our lives? Why should you control everything? The one chance we get for education in our lives — why should it be for you? Why can't it also be for us? Why can't it be for our own minds and our own interests?"

But it seems like everybody's more stuck on, like, "We provide critical thinking skills that will make you better at doing business!" That may be true or not true, but it's still within that framework. I think you're right that we lack that alternative. Even in my book, I wind up saying, "We need to abolish the market," but I don't say, "And here's what it will look like when we do it. Here's the positive alternative that will replace it." So I'm just as guilty as anybody.

I like to end my interviews by asking, "What's the most important question I didn't ask? And what's the answer?"

Where you can buy my book. [Laughter.]

PAUL ROSENBERG is a California-based writer/activist, senior editor for Random Lengths News, and a columnist for Al Jazeera English. Follow him on Twitter at @PaulHRosenberg.

No comments:

Post a Comment