Tatlin’s Tower

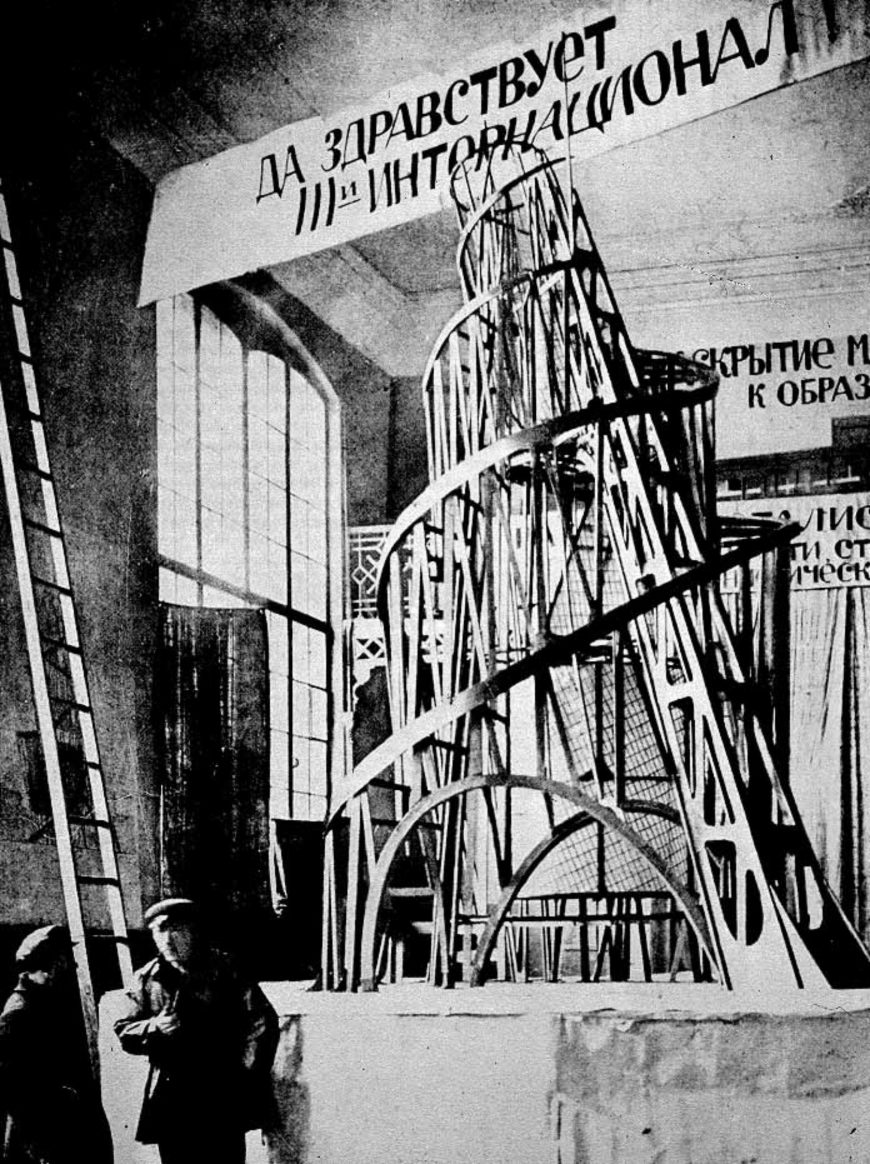

Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, commonly referred to as Tatlin’s Tower, is an iconic work of Russian modern art from the early Soviet era. It is a symbol of the utopian aspirations of the communist leaders of Russia’s 1917 October Revolution, and of the brief period when those aspirations were allied with the futuristic visions of modern artists. The original Monument has not survived and is known only from photographs, but it was never intended to be a durable object.

An ambitious plan for a sculptural structure

It was a 20-foot-tall wooden model for an enormous structure that was never constructed, in part because the material and technological resources required to build it successfully were unavailable in post-revolutionary Russia. Tatlin’s Monument thus has historical significance that goes beyond its original purpose and meaning. It is both a symbol of exalted utopian goals and an ironic monument to the economic and technological limitations of the early Soviet state.

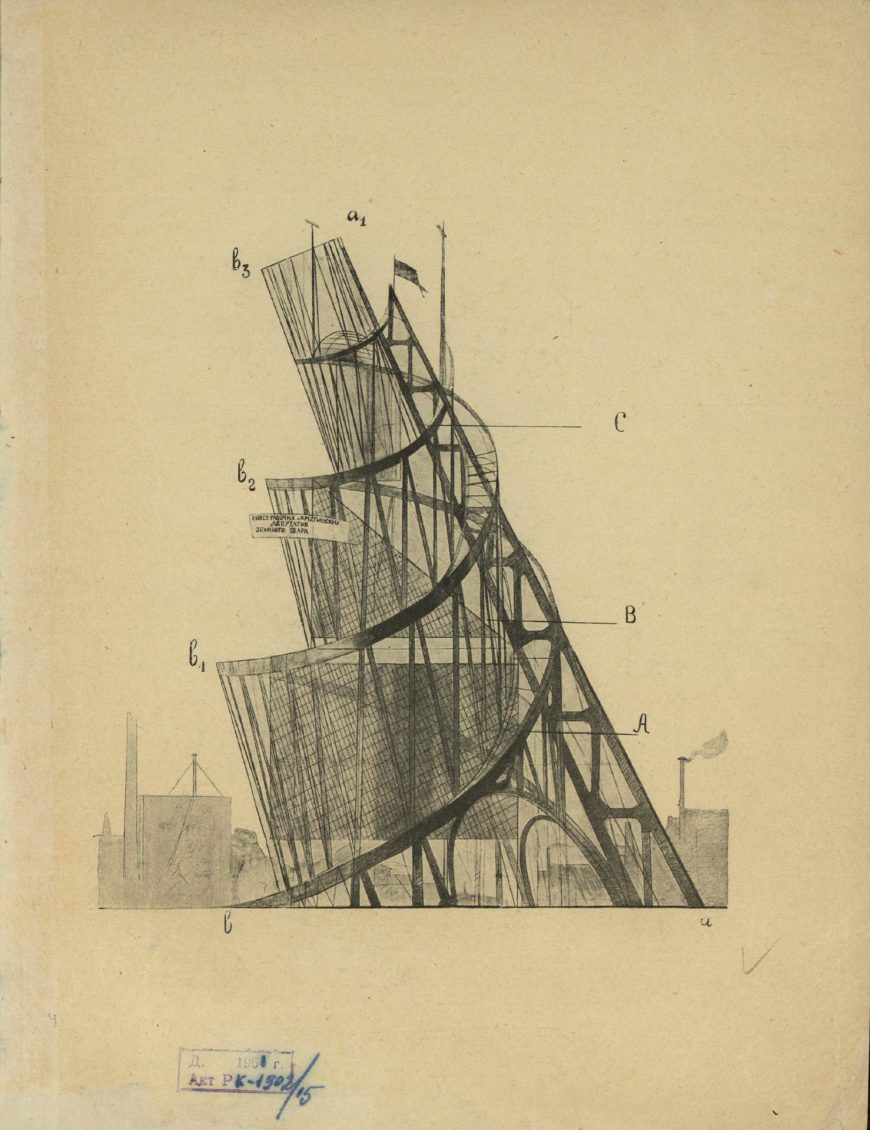

Vladimir Tatlin, Drawing of the Monument to the Third International, published in Nikolai Punin, The Monument to the Third International. (St. Petersburg, 1920)

As part of a large-scale program to replace old czarist monuments with monuments to the revolution, the huge structure was both a symbolic sculpture and functional architecture. Designed to straddle the Neva river in St Petersburg, the 1300 foot (400 meter) iron and glass Monument would surpass Paris’s Eiffel Tower in both scale and complexity. Its design consists of a contracting double helix that spirals upward, supported by a huge diagonal girder. Inside this external metal structure are four geometric volumes that were intended to revolve at different speeds.

As planned, the geometric volumes would be made of glass and serve both practical and symbolic functions. The largest and lowest was a cube, making one revolution per year, that would house meetings of the legislature of the Third International or Comintern, the international communist organization working for world revolution. The next volume up was a pyramid, making one revolution per month, that would host the Comintern executive. Above that was a cylinder, making a full revolution every day, to house the Comintern propaganda services, including the press, poster and pamphlet designers, etc.; and on top was a half sphere that revolved hourly and housed the Comintern radio station.

Model of Tatlin’s Tower, Royal Academy, London, 27 Feb 2012 (photo: TobyJ, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A Symbol of the Future

Tatlin’s design for the Monument conveyed meaning in multiple ways. The rising spirals, diagonal girder, and rotating internal volumes give symbolic form to the aspirations and dynamic forces of the world communist revolution. The planned materials of metal and glass were associated with modern engineering and construction technology, and signified the advanced, even futuristic, goals of communist society. This was further emphasized in the plan to have the interior volumes revolve mechanically, which symbolized the alignment of communist world revolution with the astronomical movement of the sun, earth, and moon, and also likened the new government to an efficient modern machine.

The Monument stressed the Comintern’s transparency to the people in its fully visible support structure and the glass interior volumes housing its various functions. The importance given to disseminating information and propaganda to the masses is also integral to the design and acknowledges the crucial role played by mass communication technologies in modern society and their power to promote world revolution.

Tatlin and Constructivism

Although Tatlin’s Monument was never built, models of it were made and displayed at political meetings, demonstrations, and parades through the 1920s. Its most important historic role, however, was its influence on Russian Soviet modern artists, particularly the Constructivists, who were conceptualizing new aesthetic practices aligned with the goals and values of the new communist society. For these artists Tatlin’s combination of modern materials, rational structure, and utilitarian forms was an important example of how artists could synthesize the historically disparate roles and forms of art, craft, and engineering to contribute to the formation of a new world.

Tatlin had established his reputation as a cutting-edge modern artist in Moscow before the 1917 revolution. He participated in The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 in 1915, where his rival Kasimir Malevich first presented Suprematist works. There, Tatlin exhibited a group of sculptures he called “counter-reliefs” and “corner counter-reliefs.” These were complex assemblages of various found non-art materials (scraps of wood, metal, glass, cardboard, wire, and rope) suspended from walls.

Pablo Picasso, Guitar, 1914, sheet metal and wire, 77.5 x 35 x 19.3 cm (MoMA).

These counter-reliefs are often associated with Picasso’s early Cubist sculptures, which Tatlin saw in Paris in 1913. Both artists rejected the Western tradition of sculpture as a unified mass made from a single material (traditionally marble or bronze), and instead created assemblages — sculptures that combine heterogeneous materials in novel ways.

Picasso’s Cubist sculptures represented objects such as guitars, glasses, and bottles, and explored the formal and spatial ambiguities previously developed in Cubist painting. Tatlin’s approach was markedly different and often completely non-representational. He was more interested in the forms, textures and physical potential of the materials themselves than in exploring the ambiguities of representation, and his works were also more radical in their relationship to space than Picasso’s.

A New Type of Sculpture

Tatlin’s earliest counter-reliefs were in a rectangular format and hung on the wall. They were composed of separate but interdependent components, and emphasized the contrasts between different textures and materials.

Vladimir Tatlin, Relief, 1914 (destroyed).

The relief reproduced here was part of a group of works titled Selection of Materials. It is an abstract composition made of scraps of wood, metal, and glass attached to a chipped and cracked stucco surface. Each material displays its texture rather than being cleaned and polished to suggest pure abstract forms. The materiality of the object and its constituent parts is fundamental to the effect of the work.

This work and others like it engage with a prominent concern of early 20th-century modern artists and writers: how non-representational form could communicate feeling directly. Faktura was a key concept in Russian debates on modern art that was connected to the artist’s use of the physical qualities of materials. Tatlin’s reliefs were understood as displays of faktura, meaning their interest was fundamentally formal and concerned with the visual and tactile properties of their material components. They had no representational content and (unlike the work of many of Tatlin’s contemporaries) no spiritual significance.

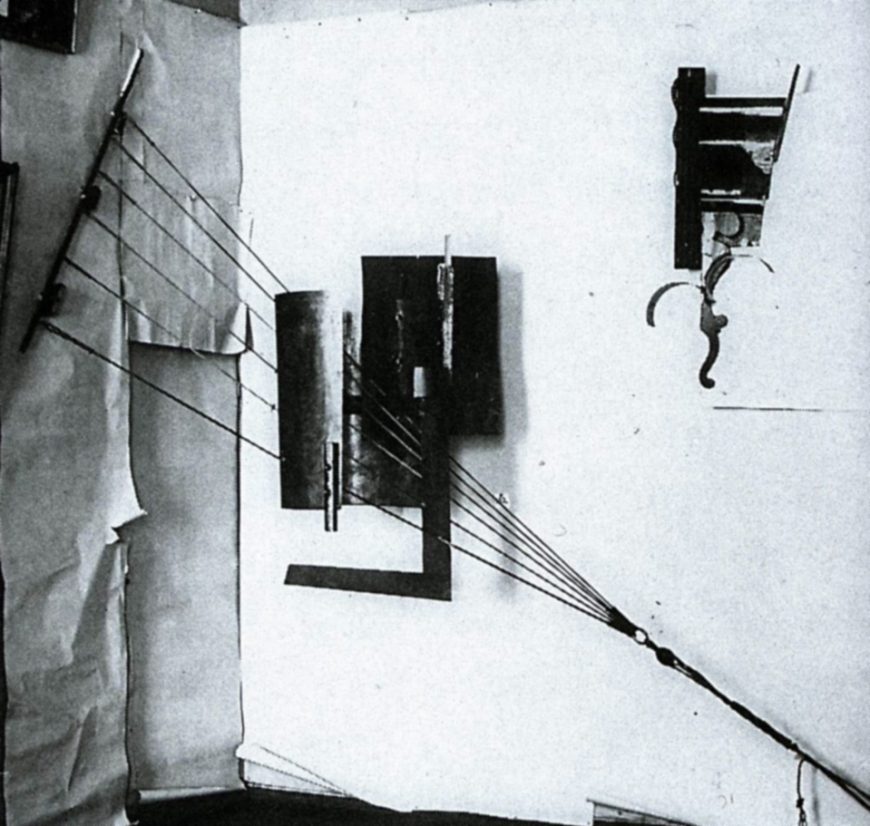

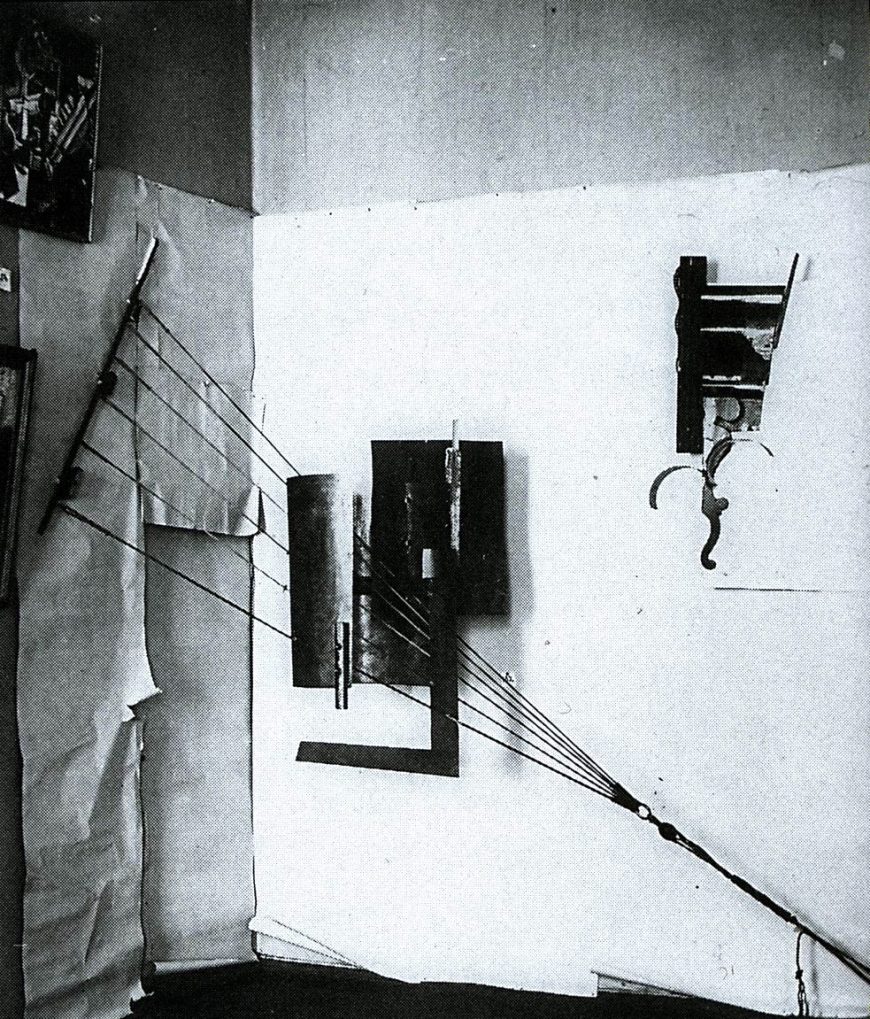

Detail of Tatlin’s sculpture at the Last Futurist Exhibition

Corner counter-reliefs

The corner counter-reliefs added another dimension to Tatlin’s work. They broke out of the limiting rectangle and created a new kind of spatially-ambiguous sculpture with indefinite boundaries. These were not self-supporting objects that could be easily moved; their form depended on the walls from which they were hung. This made their sculptural identity as independent objects even more ambiguous. The walls were part of the sculpture, and were sometimes covered with paper to emphasize their integral role in the work.

One of the most noticeable and innovative aspects of Tatlin’s corner counter-reliefs is the way they incorporate literal dynamic tension in the form of supporting ropes and wires. These allow the planes of various textures and materials to be suspended in space, and they also make physical tension a manifest part of the work’s composition.

We don’t just see the flat planes, curved forms, and bars hovering juxtaposition to each other, we see how the entire sculpture is put together. The structural relationships are laid bare. It was this literal incorporation of structure that came to be seen as an early stage in the development of Constructivism — the dominant modern art movement in Soviet Russia after 1920.

Additional resources:

Learn about the Russian Revolution

John Bowlt, Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism, 1920-1934. Revised Edition. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2017.

Christina Lodder, Russian Constructivism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983.

The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915-1932. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1992.

Inventing Abstraction 1910-1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012.

No comments:

Post a Comment