Reclaiming the co-operative history and tradition in Scotland

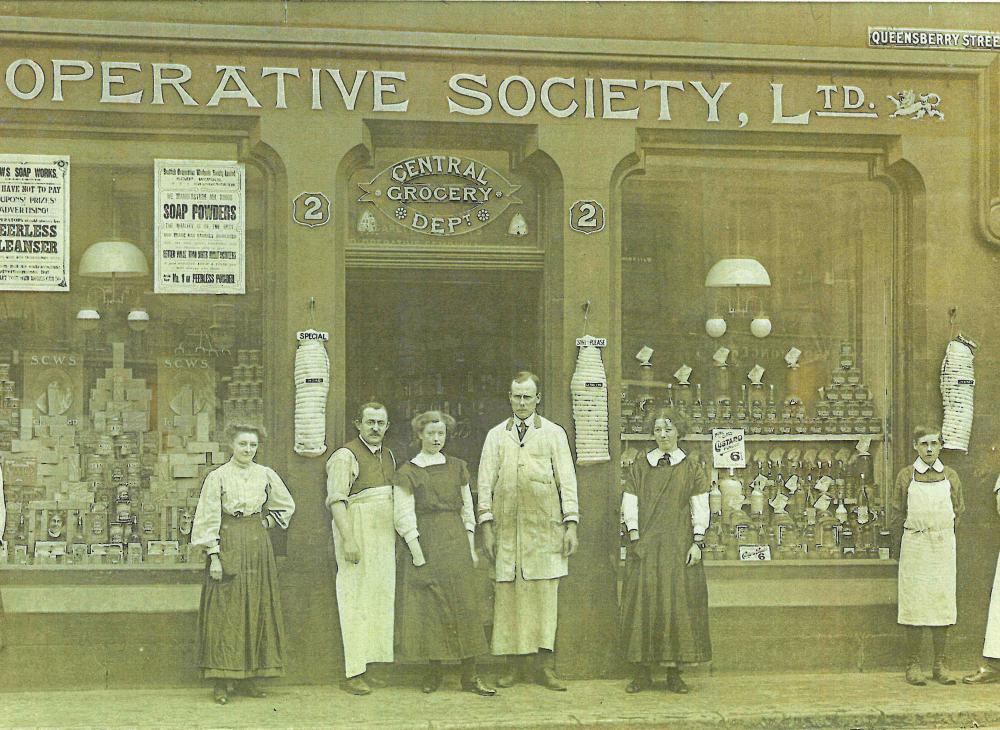

Dumfries and Maxwelltown Co-operative Shop

Something to Build On: The Co-operative Movement in Dumfries, 1847-1914, by Ian Gasse, Scottish Labour History Society.

At a time when many companies are keen to promote their commitment to ethical or sustainable retailing (whether genuine or otherwise), the Co-op is, to many, perhaps indistinguishable from any other supermarket. From its inception, however, the co-operative movement represented a different way of doing business. In Scotland, the movement developed from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, and by the early twentieth century, co-operative societies were an established feature in towns and cities across the country. Despite the rapidly changing social and economic conditions of the twentieth century, co-operatives continued to occupy a central position in many local areas well into the post-war period, and the movement’s influence within working-class communities remained significant – as those who can recall their local store and family dividend number can attest.

With this in mind, it might seem a little surprising that the history of the co-operative movement in Scotland has, to date, received little in the way of academic interest, with both the Trade Union movement and Labour Party proving more attractive to historians of the labour movement. Something to Build On, by Ian Gasse, is the latest publication to add to the movement’s rather limited historiography. This point is acknowledged by Gasse within the book’s introduction, in which he states that, despite forming a significant part of the commercial sector and making a major contribution to the areas’ wider economic, social, and cultural sectors during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there has been virtually nothing written about the movement’s origins in Dumfries and Maxwelltown. Gasse’s aim therefore, through this work, is to make a record of this history and prevent it from becoming totally ‘lost’ (though Gasse, by his own admission, points out that some aspects of the study represent more of a ‘preliminary sketch’ of its history, rather than a definitive account).

This is familiar territory for Gasse, having published two articles previously on co-operation in Dumfries, and his expertise on the subject matter shines through in this highly readable account. Drawing on society minute books (where extant) and local press reports, Gasse illustrates the various attempts to initiate and maintain consumer co-operative societies in Dumfries and Maxwelltown between 1847-1914. Although, at first glance, the scope of the study appears to be somewhat restricted by its concentration on a relatively small geographical region, a grass roots approach to the study of the movement is completely logical, given the alignment of co-operative societies with the area that they served (being reflective of local industry and economic conditions) and their strict adherence to the principle of autonomy. Furthermore, discussion is also devoted to the wider movement in Scotland, in terms of providing context for the expansion of co-operation throughout the nineteenth century and in cases where national issues had local consequences.

As the study makes clear, early efforts to install co-operation within Dumfries were by no means straightforward. Within the book’s six chapters, Gasse documents the various endeavours undertaken by co-operators to do so, including what he terms the ‘false starts’: the short-lived attempts made by the Dumfries and Maxwelltown Equitable Co-operative Society and the Dumfries Co-operative Meat Supplying Society to become established within the community between 1861-67 and 1874-76 respectively. Other ventures were to prove more successful. The Dumfries and Maxwelltown Co-operative Provision Society began trading in 1847, with the aim of providing its working-class members with quality produce at affordable prices and undercutting the area’s existing grocers and merchants (suspected of operating cartels to artificially inflate the price of basic foodstuffs).

The author Ian Gasse (right) with the book.

In this regard, the society’s commitment to the working class was evident, and the expansion of the range of goods and services on offer to its members was testament to its development. However, the decision taken by the Dumfries and Maxwelltown Co-operative Provision Society to operate as a joint-stock company was at odds with the example set by the Rochdale Pioneers to pay a dividend on member’s purchases. As Gasse explains, the principles established by the Rochdale Pioneers in 1844 subsequently provided the successful blueprint for co-operative societies throughout Britain, and though the Dumfries and Maxwelltown Co-operative Provision Society conformed to some, (including the sale of unadulterated foodstuffs and implementing a system of democratic control), the decision not to pay a dividend or to provide members with educational opportunities proved notable exceptions.

Although this system proved profitable for the society’s shareholders, the benefits afforded to the town’s working-class inhabitants were limited. Unsurprisingly, the society’s secretary reported that shareholders ‘did not grumble at all about it’, and it was only when the Queen of the South Co-operative Society came into being that change was deemed necessary. Formed in 1881, the Queen of the South Co-operative Society appears to have been borne by a desire within the local community to create a society based upon genuine co-operative principles. Faced with a rival society paying its members a dividend on purchases, and suffering from adverse trading conditions as a result, the management of the Dumfries and Maxwelltown Co-operative Provision Society took the decision to register as an ‘equitable’ co-operative society (though Gasse notes that the interests of the existing shareholders remained protected during this process).

Gasse then goes on to note the financial difficulties experienced by both co-operative societies and their eventual amalgamation to form the Dumfries and Maxwelltown Co-operative Society in 1892 and narrating its ‘solid, and at times, quite spectacular growth’ until 1914, despite coordinated opposition from the Scottish Traders’ Defence Association. In his final chapter, Gasse assesses the extent to which the various co-operative societies examined within the study attempted to extend the ideology aims of co-operation amongst the working-class communities of Dumfries and Maxwelltown, and to create what Peter Gurney has termed a ‘co-operative culture’. Though some elements of discussion could have been expanded upon (with more focus given to the activities of the local branch of the Scottish Co-operative Women’s Guild, for example), the final chapter represents the culmination of a theme woven throughout the book, that of the tension between profit and principle in co-operative enterprise.

Through Something to Build On, Gasse achieves his aim of ensuring that the history of the co-operative movement in Dumfries is not lost. Indeed, by examining the expansion of co-operative societies in the area between 1847 and 1914, the author is able to highlight the strong co-operative tradition that existed in the town. Moreover, while this study represents a welcome addition to the history of the co-operative movement in Scotland, it also provides an insight into the everyday lives of the area’s inhabitants. With economic changes and local conditions reflected in the stock lists and balance books of co-operative societies in areas like Dumfries, it is possible to gauge the incremental, but significant, improvements to the lives of the working classes during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

00:00 The Four Minute Warning: The Tide's Out/James MacLellan's Favourite/Dougie's Decision/The Ferryman/Lady Doll Sinclair

No comments:

Post a Comment