US Starts 2026 by Bombing Venezuela and Kidnapping Its President, Setting a Tone of Imperialist Violence for the Year

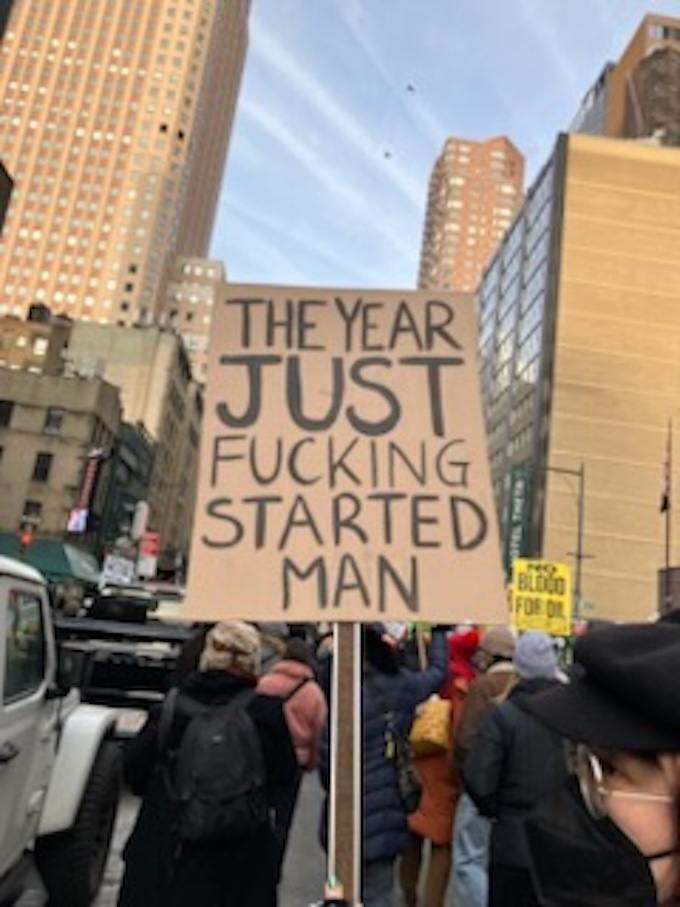

NYC demonstration against the bombing of Venezuela and kidnapping of its president. Photo: Susie Day.

With its violent military intervention into Venezuela–a country I used to live in–the U.S. has begun this year with entitled and undisguised imperialism. The unapologetic kidnapping of Nicolas Maduro and of Celia Flores (not just a wife as the media refers to her, but also former head of the National Assembly) and killing of at least 40 Venezuelans aims to cement and normalize the U.S.’s standard operating procedure for international relations as violence and control. It will take Venezuela’s oil and the DRC’s tech minerals, and to hell with Global South self-determination, agency, and ownership.

I remember when I lived in Venezuela and we talked about what we would do if the U.S. attacked. We were already facing other kinds of attacks, including basic food shortages orchestrated by private companies, destabilization attempts, right-wing violence, and English-language mainstream media lies. The conversation particularly came up around elections, when the shortages and destabilization typically increased, and U.S. attacks felt less hypothetical.

Even then, though, we would balance the very real and long history of violent U.S. interventions in Latin America with skepticism. How could they kill innocent people and bomb what felt like to me the closest thing to paradise? Venezuela was never a utopia – there were mistakes and much work to do, but the Andean mountains were intensely green, the coastal waters a peaceful turquoise, the nights full of fairy fog that you could see drifting down the streets. The days were full of the laughter of the tiny children I taught as part of our participatory education project. We solved our own local problems as an organized community, turned empty lots into community gardens, and there was always, always, political debate and high political literacy. People knew their constitution, often by heart, knew the laws, and the news. Venezuelans had and have this infinite urge to dance, even on moving buses or after two-day long meetings. How could anyone consider destroying that world? It felt inconceivable. It didn’t make sense, and it still doesn’t.

Yet we all know that beautiful Gaza, with its beaches, shops, delicious zaatar bread, hospitals, books, and resilient people, has been turned into rubble and whole families wiped out. The U.S.-led destruction of Afghanistan and Iraq ruined people, communities and saw key cultural and archaeological sites irreparably damaged, and artifacts looted. I live in Mexico now, and here alone, the U.S. has used NAFTA and the so-called “War on Drugs” to militarize this beautiful country and systematically turn it into a vast grave (with 131,000 forced disappearances) and into an obedient neoliberal production line for nearshoring U.S. companies. So, in Venezuela, I guess we should have been less skeptical. Friends there messaged me on Saturday in shock, their ears ringing from the sounds of bombs. New Year’s weekend wasn’t meant to be this.

However, throughout 2025, the U.S. had asserted itself more openly as global police chief at the service of big business. It “negotiated” (pressured) a “ceasefire” in the DRC which would give it access to the country’s highly sought-after tech minerals and metals and to security control, and it has supported Israel, bombed Nigeria, and killed Venezuelans with complete impunity. It closed its borders to refugees in violation of international law, and breached migrant and human rights within its own borders. It also bombed Syria, Iraq, Iran, Yemen, and Somalia. It carried out or was partner to 622 overseas bombings in total, and also intervened in manipulative ways, such as Trump’s comments days before the Honduran election in November that led to the victory of the right-wing candidate he backed, or the U.S.’s role in the international “Gang Suppression Force” in Haiti.

While global institutions like the International Criminal Court and the UN have demonstrated their ineffectiveness at doing anything at all about the U.S.’s illegal sanctions against Cuba, the genocide in Gaza, or climate destruction, Trump has been able to fortify the U.S. as a force that actually decides international affairs.

In his press conference Saturday, Trump said the U.S. would be selling Venezuelan oil. Though he laid the groundwork for the military intervention into Venezuela with evidence-free talk of drug cartels, bombing what were likely fishing boats in the second half of 2025, most people knew this was always about regaining control over the country with the largest known oil reserves. However, Venezuela also represents defiance. The U.S. has sanctioned the country for such behavior for over a decade, killing or contributing to the deaths of over 40,000 people in 2017–18 alone.

The U.S. doesn’t just treat the Global South as a resource buffet. In order to secure its access to the goods, it wants the countries’ governments at its beck and call. Venezuela, especially during the 2010s and through initiatives like CELAC, was playing a role of uniting Latin America against such dominance and towards independence and social and economic alternatives.

The bombing of Venezuela, beyond the oil itself, is about U.S. control over Latin America and part of a right-wing push back against movements, grassroots empowerment, and alternatives to violent capitalism. Beyond Bukele in El Salvador and Milei in Argentina, in 2025 the right wing also won in Bolivia, Honduras, and Chile. With Trump, these “leaders” are furthering racist, homophobic, sexist, and privatization agendas.

Normalizing empire and global human rights violations

Beyond the horrific event itself, the events of January 3 are part of a move towards normalizing a global state of danger, insecurity, human rights abuses, and disregard for international law. It does not matter what anyone thinks of Maduro; whether he won the 2025 election is an important discussion for another place and time. The U.S. has no right to determine the heads of other countries. It wants to be, but is not the world boss, and beyond that, has no moral standing to decide or control anything.

But Saturday’s move, as a continuation of U.S. policy in 2025, upholds military intervention as a solution to problems. It is a signal to wayward countries to obey. Such imperialism not only kills people, in the long term it perpetuates racist tropes of Global South countries that can’t run themselves, while legitimizing U.S.- and euro-centrisim that stipulates their monopoly on wisdom and democracy. Imperialism scares its victims into silence and submission and cements a global apartheid dynamic where some regions are politically and financially controlled, subjected to unlivable wages and to resource robbery. Through debt systems and trade and income inequalities, rich countries have drained US$152 trillion from the Global South since 1960.

The intervention machine is rigging the world for U.S. big business interests, at the price of Global South dignity and agency. For invaded and intervened countries, there are hidden impacts as well; lower self-worth and an unsubstantiated belief that one’s education, art, and inventions are inferior, disillusion with organizing and movements, and often, a need to migrate that is then met with rejection by those forces causing that need – as of course is the case with the U.S.

The Venezuelan people are not a threat. The country doesn’t even produce or traffic significant amounts of drugs. In reality, much of the cruelty and harm globally is coming from the U.S. The Trump government and the U.S. elites are the ones committing human rights violations, shirking democracy by orchestrating coups like the one on Saturday morning and shirking legality let alone decency, by killing people in Venezuelan boats under the pretext of opposing drug trafficking, but without any trials or any proof. With each intervention Saturday’s, the U.S. furthers its and Israel’s impunity for war crimes, abuses, and violations.

Robert Reich

January 4, 2026

Donald Trump speaks to the press. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

In the first year of Donald Trump’s second term, he imposed his thuggery on the United States. In the second year, apparently he will impose it on the hemisphere.

America’s takeover of Venezuela — because it’s in our “backyard” and we didn’t like its leader — strengthens Vladimir Putin’s claim over Ukraine, Xi Jinping’s over Taiwan, and Benjamin Netanyahu’s over the West Bank and Gaza.

Make no mistake: Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro was a vicious dictator who harmed Venezuela and its people. But the world is populated by many vicious dictators. We don’t take over their countries.

The postwar order was supposed to stop thugs who use aggression to take over their “backyards,” as Hitler had done in Europe and Japan in East Asia.

But Trump is now reverting back to the pre-World War II, might-makes-right, spheres-of-power, order.

For more than 80 years, America’s moral authority has rested on our claim to be on the side of democracy. That claim was often belied by American aggression that bolstered dictators — in Vietnam in the 1960s, in Latin America in the 1970s, and more recently in Afghanistan and Iraq — but it at least gave a patina of legitimacy to our alliances and to our “soft power” through USAID and the United Nations.

Now we’re back to the rawest form of neo-imperialism.

“We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country,” Trump explained on Saturday morning.

Let’s be clear: When it comes to Venezuela’s giant oil reserves, America’s oil companies will be making money for themselves. During the 2024 campaign they made a deal with Trump on which they’re still cashing in.

In December, Trump tried to justify his blockade of Venezuela by referring to its “expropriation” of U.S. oil company assets, presumably referring to the nation’s nationalization of its oil reserves in 1976.

“They’re not going to do that again,” Trump told reporters. “We had a lot of oil there. As you know they threw our companies out, and we want it back.”

Rubbish. The 1976 nationalization was the culmination of decades of efforts by both left-wing and right-wing administrations in Venezuela to regain financial control over oil that earlier had largely been given away.

Trump seems intent on carving up the world into three large power blocs: one under the thuggery of Putin, the second under the thuggery of Xi, and the third under Trump’s thuggery (allied with sou-thugs like Israel’s Netanyahu).

To be a “neighbor” of a thug is to surrender to the thug’s wishes or to the thug’s direct control. Within Putin’s thuggery fall Ukraine and quite possibly Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the rest of the former Soviet bloc.

Within Xi’s thuggery fall Taiwan, Tibet, Mongolia, and possibly Nepal.

Within Trump’s thuggery fall the rest of Latin America, including Mexico, and possibly even Greenland and Canada.

Beware. The Trump world order makes the world safe only for major tyrants.

Robert Reich's new memoir, Coming Up Short, can be found wherever you buy books. You can also support local bookstores nationally by ordering the book at bookshop.org

COMMENT: Is the US now a “gangster state”?

Is the US now a gangster state? That is the question Indian commentators were asking as the news broke that a US special military operation struck Caracas in the early hours of the morning on January 3.

My phone started ringing off the hook this morning as the news broke by Indian TV stations asking for commentary. The attack on Venezuela is a top story in the Global South and will have far reaching consequences. It is being universally condemned as a lawless attempt at a colonial asset grab of Venezuela’s vast oil reserves by the US. It shreds what little credibility America has left as the protector of the international rules-based order and the upholder of liberal and enlightened values.

“What is the difference between what the US has just done and what [Russia’s President Vladimir] Putin has done in Ukraine?” asked a former Indian ambassador on one of the panels.

The Global South has been watching the development of the growing East-West clash closely. Indians have been paying especially close attention. The BRICS bloc is rising and India just overtook Japan in nominal GDP terms after passing it in PPP adjusted terms two years ago. Following the invasion of Ukraine four years ago, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi was careful to sit on the fence as he tried to get caught up in the conflict.

But now the world’s largest democracy is in shock at the blatant imperialistic and unjustifiable, from Delhi’s perspective, attack on another sovereign nation in defiance of international law.

“Territorial integrity and respect for sovereignty should be fundamental, but here we simply see the implementation of the Monroe doctrine – a doctrine that the US has been following for decades,” the ambassador said. Venezuela’s defence minister Diosdado Cabello described the attack as a “terrorist attack” and “foreign aggression” has called the US attack, the India media lead with in the mid-morning reports.

At the Indian hosted G20 summit in Delhi two years ago, Modi tried to build a middle-of-the-road-coalition between the emerging world and the West. At that meeting the African Union (54 countries) were added to the “G20” and pointedly Putin and China’s president Xi Jinping stayed away. At the same time, South America, led by Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva were also steering a middle course, keeping their distance from the more militant Putin and Xi who see their clash with the West as a rivalry framed under the BRICS organisation rather than the G20. Much of the Asian and Latin America Global South members saw their block in economic, not political, terms and wanted to maintain good relations with both sides.

That good will had already evaporated long before the attack on Venezuela. Modi surprised everyone by turning up at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in China in the autumn and hobnobbing with Xi and Putin, as well as other pariahed leaders from the emerging world like North Korea’s Kim Jong Un and Belarus president Alexander Lukashenko. Since then, Putin travelled to New Delhi in December for a working trip where he signed billions of dollars of business deals with Modi, sold him arms and established what the two leaders called a new “no limits” partnership to rival Russia’s “no limits” ties with China.

IntelliNews is becoming increasingly popular in India as it focuses on business and has a non-European perspective on the intra-emerging market relations – especially the Indo-Russian relationship where we have bureaus in both Moscow and New Delhi and focus on the bilateral relations. Over the last two years, the Indian commentators on panels on which I have participated have become increasingly belligerent at India’s treatment by the US in particular.

India has been increasingly annoyed by the bullying by the State Department to cut off Russian oil imports on the one hand, and the ongoing weapons sales of things like F-16 to Pakistan, with which India briefly went to war last year. But the entire Indian political firmament was incensed by Trump’s imposition of 50% tariff rate on India last autumn when it refused to stop imports of Russian oil. The foreign ministry issues an extremely angry letter pointing out that Europe still imports more Russian oil than India and called out the Western allies for practising double standards.

“The nacro-trafficking is an excuse. The corruption is an excuse. This attack is a clear violation of international law. This is about energy resources and this is about the close relationship between Venezuela and China. This is a new imperialism. It goes against the UN Charter. It goes against international law. And it goes against democracy,” said a former Indian ambassador to the Latin America on another panel. “In the eyes of Trump 2.0 there is no such thing as international law. The veneer of “freedom’s champion” has been stripped away and the double standards laid bare.”

“They want us to stop importing cheap Russian oil, which is in India’s national interests, and back their sanctions, but where are they when we want help with our problems like the tensions on the Pakistan and Chinese borders?” former Indian ambassador to the EU, Bhaswati Mukherjee said on one panel. “The war in Ukraine is a European problem. It has nothing to do with us. Let the Europeans sort it out,” summing up an increasingly widespread sentiment.

The word “colonialism” comes up increasingly frequently and was at the centre of this morning’s commentary of the US attack on Venezuela.

A former Indian major general on another panel this morning noted that the Trump administration is primarily interested in getting access to Venezuela’s vast oil reserves, critical minerals and opening up its markets to the US big-pharma multinational firms. He specifically framed the US as a “declining superpower” in a global rivalry for dominance with China – in keeping with the main tenants of Trump’s new National Security Strategy that aims to “contain” China’s dominance in the Indo-Pacific region.

“The US is irked by Venezuela’s oil exports to Cuba when it is refined and sold to China. That is what the Trump administration wants to cut off,” the General said. China is heavily invested in Latin America, a market that the US has underemphasized until now. It has only been under the Trump administration that the importance of countering China’s growing influence in the continent has become more important such as the spat over China’s investments into the Panama Canal.

The attack on Venezuela will only pour fuel on this flame and bolster the Putin-Xi anti-western camp. Tellingly, after two years of dithering, last January Indonesia, the fourth most populous country in the world and the largest Muslim nation, came down off the fence and joined the BRICS+ organisation in a major coup for Xi and Putin. And while the US and Europe bicker over trade and tariffs, as bne IntelliNews has reported, the Global South have been busy building up the GEMIs (Global Emerging Markets Institutions) – a Global South network of interconnecting trade and security deals that entirely exclude the Western institutions and powers that have dominated the global economy for most of the last 500 years.

The General echoed Mukherjee by calling for Washington to end its perennial policy of seeking regime change in countries that are not friendly to the US, and criticising the US growing domestic economic problems and growing societal divisions.

“The US would be better to focus on its own economic policy and consolidate as it is only going from bad to worse instead of concentrating on fixing its own economy. Instead of 'Making America Great Again' its going to go from gasp to gasp to gasp."

Shaun TANDON

Donald Trump returned to office vowing to be the peace president. Nearly a year later, he is embracing war on multiple fronts.

Trump on Saturday ordered large-scale military strikes in Venezuela and announced that leftist leader Nicolas Maduro had been captured and flown out of the country.

The raid to kick off the new year comes after the US military on Christmas Day hit Nigeria, in what Trump said was an operation targeting jihadists who had attacked Christians.

And hours before the attack in Venezuela, Trump warned of another US intervention in a third region, saying US forces were “locked and loaded” if Iran’s clerical state kills protesters who have taken to the streets.

The enthusiasm for war would seem at odds for a president who has loudly declared that he deserves the Nobel Peace Prize for supposedly ending eight wars, a claim that is highly disputable.

In his second inaugural address on January 20 last year, Trump said: “My proudest legacy will be that of a peacemaker and unifier.”

But soon after, Trump rebranded the Defense Department as the “Department of War.”

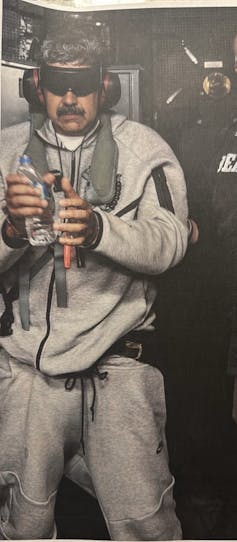

US President Donald Trump said Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro had been captured – Copyright AFP/File Jim WATSON, Federico PARRA

Both Trump and his aides insist that military muscle is the path to real peace.

“We’re making peace through strength. That’s what we’re doing,” Trump told a rally last month in Pennsylvania.

“Peace through strength” was famously a catchphrase of Ronald Reagan, as he promoted a massive military build-up at the end of the Cold War, and was attributed to the Roman emperor Hadrian who built up defenses.

But the strategy was generally understood as a way to prevent war from beginning.

– ‘So-called nation-builders’

Making his love of force even more striking, Trump has not only described himself as a peacemaker but has spoken for years against US interventionism.

Declaring “America First,” he cast himself as a different kind of Republican than the party’s last president George W. Bush, whose administration he castigated as warmongers over the Iraq invasion of 2003.

In a speech in Riyadh in May, Trump said that “so-called nation-builders wrecked far more nations than they built” and failed to understand countries where they intervened.

In one key difference with Bush, Trump has made no pretense of long-term commitment.

He last year ordered the bombing of Iranian nuclear sites in support of an Israeli attack as well as strikes in Syria in retaliation for the killings of US forces.

But like Bush, Trump cares little about UN or other international conventions on war.

The Trump administration argues that Maduro faced a warrant for drug charges in the United States, but Maduro’s government is a UN member, even if most Western countries consider him illegitimate following elections riddled with irregularities.

Senator Ruben Gallego, a Democrat and Iraq war veteran, called Venezuela the “second unjustified war in my lifetime,” although he agreed Maduro was a dictator.

“It’s embarrassing that we went from the world cop to the world bully in less than one year. There is no reason for us to be at war with Venezuela,” he said on X.

In one irony, the latest Nobel Peace Prize, so coveted by Trump, went to Venezuela’s opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, whose name the US president did not appear initially to know.

Trump, however, has won one peace prize since taking office.

FIFA’s president, Gianni Infantino, presented Trump last month with a prize from football’s governing body ahead of the US co-hosting the World Cup.

Infantino said that Trump, who has taunted migrants from developing countries and threatened violence against domestic opponents, was being recognized for his “exceptional and extraordinary actions to promote peace and unity around the world

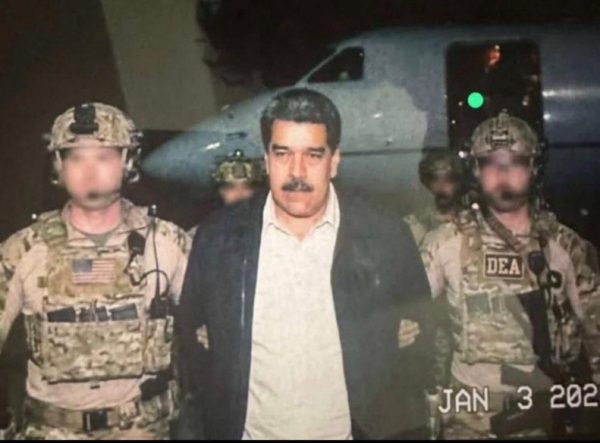

An image of a captured Nicolás Maduro released by President Donald Trump on social media.

An image of a captured Nicolás Maduro released by President Donald Trump on social media.

Truth Social

In the dead of night during the holidays, the United States launched an operation inside a Latin American country, intent on seizing its leader on the pretext that he is wanted in U.S. courts on drug charges.

The date was Dec. 20, 1989, the country was Panama, and the wanted man was General Manuel Noriega.

Many people in the Americas waking up on Jan. 3, 2026, may have been feeling a sense of déjà vu.

Images of dark U.S. helicopters flying over a Latin American capital seemed, until recently, like a bygone relic of American imperialism – incongruous since the end of the Cold War.

But the seizure of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, along with his wife, Cilia Flores, recalls an earlier era of U.S. foreign policy.

U.S. President Donald Trump announced that, in an overnight operation, U.S. troops captured and spirited the couple out of Caracas, the Venezuelan capital. It followed what Trump described as an “extraordinary military operation” involving air, land and sea forces.

Maduro and his wife were flown to New York to face drug charges. While Maduro was indicted in 2020 on charges that he led a narco-terrorism operation, his wife was only added in a fresh indictment that also included four other named Venezuelans.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio said he “anticipates no further action” in Venezuela; Trump later said the he wasn’t afraid of American “boots on the ground.”

Whatever happens, as an expert on U.S.-Latin American relations, I see the U.S. operation in Venezuela as a clear break from the recent past. The seizure of a foreign leader – albeit one who clung to power through dubious electoral means – amounts to a form of ad hoc imperialism, a blatant sign of the Trump administration’s aggressive but unfocused might-makes-right approach to Latin America.

It eschews the diplomatic approach that has been the hallmark of inter-American relations for decades, really since the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s took away the ideological grab over potential spheres of influence in the region.

Instead, it reverts to an earlier period when gunboats — yesteryear’s choppers — sought to achieve U.S. political aims in a neighboring region that American officials treated as the “American lake” – as one World War II Navy officer referred to the Caribbean.

Breaking with precedent

The renaming of the Gulf of Mexico as the “Gulf of America” – one of the earliest acts of the second Trump administration – fits this new policy pivot.

But in key ways, there is no precedent to the Trump administration’s operation to remove Maduro.

Never before has the U.S. military directly intervened in South America to effect regime change. All of Washington’s previous direct actions were in smaller, closer countries in Central America or the Caribbean.

The U.S. intervened often in Mexico but never decapitated its leadership directly or took over the entire country. In South America, interventions tended to be indirect: Lyndon Johnson had a backup plan in case the 1964 coup in Brazil did not succeed (it did); Richard Nixon undermined the socialist government in Chile from 1970 on but did not orchestrate the coup against President Salvador Allende in 1973.

And while Secretary of State Henry Kissinger – the architect of U.S. foreign policy under Nixon and his successor, Gerald Ford – and others encouraged repression against leftists throughout the 1970s, they held back from taking a direct part in it.

A post-Maduro plan?

U.S. officials long viewed South American countries as too far away, too big and too independent to call for direct intervention.

Apparently, Trump’s officials paid that historical demarcation little heed.

What is to happen to Venezuela after Maduro? Taking him into U.S. custody lays bare that the primary goal of a monthslong campaign of American military attacking alleged drug ships and oil tankers was always likely regime change, rather than making any real dent in the amount of illegal drugs reaching U.S. shores. As it is, next to no fentanyl leaves Venezuela, and most Venezuelan cocaine heads to Europe, anyway.

What will preoccupy many regional governments in Latin America, and policy experts in Washington, is whether the White House has considered the consequences to this latest escalation.

Trump no doubt wants to avoid another Iraq War disaster, and as such he will want to limit any ongoing U.S. military and law enforcement presence. But typically, a U.S. force changing a Latin American regime has had to stay on the ground to install a friendly leader and maybe oversee a stable transition or elections.

Simply plucking Maduro out of Caracas does not do that. The Venezuela constitution says that his vice president is to take over. And Vice President Delcy Rodriguez, who is demanding proof of life of her president, is no anti-Maduro figure.

Regime change would require installing those who legitimately won the 2024 election, and they are assuredly who Rubio wants installed next in Miraflores Palace.

Conflicting demands

With Trump weighing the demands of two groups – anti-leftist hawks in Washington and an anti-interventionist base of MAGA supporters – a power struggle in Washington could emerge. It will be decided by men who may have overlapping but different reasons for action in Venezuela: Rubio, who wants to burnish his image as an anti-communist bringer of democracy abroad; Trump, a transactional leader who seemingly has eyes on Venezuela’s oil; and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, who has shown a desire to flex America’s military muscle.

What exactly is the hierarchy of these goals? We might soon find out. But either way, a Rubicon has been crossed by the Trump administration. Decades of U.S. policy toward neighbors in the south have been ripped up.

The capture of Maduro could displace millions more Venezuelans and destabilize neighboring countries – certainly it will affect their relationship with Washington. And while the operation to remove Maduro was clearly thought out with military precision, the concern is that less attention has been paid to an equally important aspect: what happens next.

“We’re going to run the country” until a “safe, proper and judicious transition” occurs, the Trump promised. But that is easier said than done.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

I listened to the January 3 press conference with a knot in my stomach. As a Venezuelan American with family, memories, and a living connection to the country being spoken about as if it were a possession, what I heard was very clear. And that clarity was chilling.

The president said, plainly, that the United States would “run the country” until a transition it deems “safe” and “judicious.” He spoke about capturing Venezuela’s head of state, about transporting him on a U.S. military vessel, about administering Venezuela temporarily, and about bringing in U.S. oil companies to rebuild the industry. He dismissed concerns about international reaction with a phrase that should alarm everyone: “They understand this is our hemisphere.”

For Venezuelans, those words echo a long, painful history.

Let’s be clear about the claims made. The president is asserting that the U.S. can detain a sitting foreign president and his spouse under U.S. criminal law. That the U.S. can administer another sovereign country without an international mandate. That Venezuela’s political future can be decided from Washington. That control over oil and “rebuilding” is a legitimate byproduct of intervention. That all of this can happen without congressional authorization and without evidence of imminent threat.

We have heard this language before. In Iraq, the United States promised a limited intervention and a temporary administration, only to impose years of occupation, seize control of critical infrastructure, and leave behind devastation and instability. What was framed as stewardship became domination. Venezuela is now being spoken about in disturbingly similar terms. “Temporary Administration” ended up being a permanent disaster.

Under international law, nothing described in that press conference is legal. The UN Charter prohibits the threat or use of force against another state and bars interference in a nation’s political independence. Sanctions designed to coerce political outcomes and cause civilian suffering amount to collective punishment. Declaring the right to “run” another country is the language of occupation, regardless of how many times the word is avoided.

Under U.S. law, the claims are just as disturbing. War powers belong to Congress. There has been no authorization, no declaration, no lawful process that allows an executive to seize a foreign head of state or administer a country. Calling this “law enforcement” does not make it so. Venezuela poses no threat to the United States. It has not attacked the U.S. and has issued no threat that could justify the use of force under U.S. or international law. There is no lawful basis, domestic or international, for what is being asserted.

But beyond law and precedent lies the most important reality: the cost of this aggression is paid by ordinary people in Venezuela. War, sanctions, and military escalation do not fall evenly. They fall hardest on women, children, the elderly, and the poor. They mean shortages of medicine and food, disrupted healthcare systems, rising maternal and infant mortality, and the daily stress of survival in a country forced to live under siege. They also mean preventable deaths, people who die not because of natural disaster or inevitability, but because access to care, electricity, transport, or medicine has been deliberately obstructed. Every escalation compounds existing harm and increases the likelihood of loss of life, civilian deaths that will be written off as collateral, even though they were foreseeable and avoidable.

What makes this even more dangerous is the assumption underlying it all: that Venezuelans will remain passive, compliant, and submissive in the face of humiliation and force. That assumption is wrong. And when it collapses, as it inevitably will, the cost will be measured in unnecessary bloodshed. This is what is erased when a country is discussed as a “transition” or an “administration problem.” Human beings disappear. Lives are reduced to acceptable losses. And the violence that follows is framed as unfortunate rather than the predictable outcome of arrogance and coercion.

To hear a U.S. president talk about a country as something to be managed, stabilized, and handed over once it behaves properly, it hurts. It humiliates. And it enrages.

And yes, Venezuela is not politically unified. It isn’t. It never has been. There are deep divisions, about the government, about the economy, about leadership, about the future. There are people who identify as Chavista, people who are fiercely anti-Chavista, people who are exhausted and disengaged, and yes, there are some who are celebrating what they believe might finally bring change.

But political division does not invite invasion.

Latin America has seen this logic before. In Chile, internal political division was used to justify U.S. intervention, framed as a response to “ungovernability,” instability, and threats to regional order, ending not in democracy, but in dictatorship, repression, and decades of trauma.

In fact, many Venezuelans who oppose the government still reject this moment outright. They understand that bombs, sanctions, and “transitions” imposed from abroad do not bring democracy, they destroy the conditions that make it possible.

This moment demands political maturity, not purity tests. You can oppose Maduro and still oppose U.S. aggression. You can want change and still reject foreign control. You can be angry, desperate, or hopeful, and still say no to being governed by another country.

Venezuela is a country where communal councils, worker organizations, neighborhood collectives, and social movements have been forged under pressure. Political education didn’t come from think tanks; it came from survival. Right now, Venezuelans are not hiding. They are closing ranks because they recognize the pattern. They know what it means when foreign leaders start talking about “transitions” and “temporary control.” They know what usually follows. And they are responding the way they always have: by turning fear into collective action.

This press conference wasn’t just about Venezuela. It was about whether empire can say the quiet part out loud again, whether it can openly claim the right to govern other nations and expect the world to shrug.

If this stands, the lesson is brutal and undeniable: sovereignty is conditional, resources are there to be taken by the U.S., and democracy exists only by imperial consent.

As a Venezuelan American, I refuse that lesson.

I refuse the idea that my tax dollars fund the humiliation of my homeland. I refuse the lie that war and coercion are acts of “care” for the Venezuelan people. And I refuse to stay silent while a country I love is spoken about as raw material for U.S. interests, not a society of human beings deserving respect.

Venezuela’s future is not for U.S. officials, corporate boards, or any president who believes the hemisphere is his to command. It belongs to Venezuelans.

I have met Maduro, Delcy Rodriguez too. And before them Chavez. I have walked around the streets of Caracas. Through other locales in Venezuela as well. And some Communes too. All that was some time back. It is all totally irrelevant. What matters, then? That I am a citizen of the United States. And so I should work to stop my country’s latest infamy. And about the only means I have available is to write.

U.S. malevolence is now directed at Venezuela. On the one hand, we steadily escalated violence in surrounding waters with extra judicial murders. It didn’t work. Then we imposed economic war in the form of a full blockade. Doing so targeted the population. It said to Venezuelans, overthrow your government to stop the punishment we impose. It didn’t work. So now we bombed Caracas and some other “targets.” Trump says, we will run the country. We will get back the oil under their ground that they stole. Our imperial violence will win. So why war? Why now? Put differently, war, what is it good for? Who is it good for?

These assaults have nothing to do with drugs. Trump doesn’t kidnap real drug runners. He pardons them. But if it’s not drugs, what is the motivation?

To try to explain Trump’s behavior is fraught with difficulty even after the fact. Kurt Vonnegut might have said it is like trying to tell time using a cuckoo clock from hell. Nonetheless, I think the three best candidate explanations are grabbing oil power and wealth, exacting vengeance writ large, and perpetual distraction.

Oil, because Trump doesn’t care a whit about the planet and its inhabitants. Instead, like others before him, he likes the idea of controlling as much of that productive but supremely deadly substance as possible. It is because oil conveys power. Because oil impacts prices. Because oil can enrich those who hold it. Trump doesn’t hide this motive. He flaunts it. And Venezuela has by far the largest oil reserves in the world. What a prize. Trump’s true base, his billionaire base, will benefit big from taking over Venezuela’s oil while they still can, before Trump is defanged and removed.

Vengeance, because Trump thinks, like most American President’s have thought, that the U.S. owns the world. We don’t invade anywhere because everywhere is ours. We can’t invade what we own. We don’t attack anyone because anything we do is by definition defense. More, when Venezuela nationalized its oil industry (in 1976 and later intensified under Chavez), Trump believes it stole our oil. After all, we own the world. Everything is ours and everything includes oil sitting under Venezuela. So sure, let’s punish the Venezuelan thieves. Let’s grab back what’s ours. Vengeance is obviously warranted. More, when Cubans overthrew Batista, Castro stole the country he resided in. Fancy that. It’s just imperial calculus. Controlling Venezuela will hurt Cuba.

But beyond immediate motivations, I fear that the Venezuela coup may be a prelude rather than a conclusion. Even a training exercise. Cuba? Mexico? Greenland? The whole damn Hemisphere? I’d have said this was too dangerous for elites to even contemplate, except the elites we are talking about are Trump and his toadies.

Distraction, because Trump’s popularity is being seriously eroded and a one-sided war is typically very effective for rallying nationalist fervor. It will turn peoples’ eyes away from ignores silly niceties like law and morality, won’t it? Will the stench of war and a cacophonous demand for patriotism align mainstream media with Trump’s wishes? If unchallenged it most likely will. Will it align the population with Trump’s wishes? Be patriotic, dammit. I think the odds of that alignment occurring are way less. But will the public not only dislike but also resist imperial war making?

All Trump’s motives, pursued consistent with overarching imperial agendas, make U.S. actions illegal, immoral, and considering human survival, utterly irrational.

Trump’s choice also, however, poses an interesting if rather obscene question. Some ask it this way. What can one now say if China invades Taiwan? Or what can one say if Russia kidnaps Zelensky? It turns out imperialism is okay and even excellent for us, but not for others. And certainly not for others arrayed against us. I want to ask a different question. It’s more general. It’s meant to highlight—egad—the morality of the situation.

Does one nation (the U.S.) have a right to kidnap the President and bomb the citizens of another nation (Venezuela) because the bombardier nation accuses the target nation of some sort of nefarious activity? Proof be damned. Or for that matter, even if proof of nefarious activities were to exist, would it make international violence okay? Bombs away.

How about if the bombardier nation can easily prove incontestable acts by the target nation that threaten the bombardier’s very existence? Would it be wrong for Venezuela, Iran, or for that matter any nation where people are endangered by global warming, U.S. trade policies, or the U.S. military to bomb the U.S. and kidnap Trump? If that would be immoral, then isn’t such behavior also immoral for us to enact?

So what now? Trump says we will run Venezuela. We will get the oil flowing faster than it ever has. Drill, baby drill and do it unlike ever before. With our corporations in charge.

Does that mean we will put U.S. officials into Venezuela to conduct government affairs? Or we will find Quislings in Venezuela to do our bidding? So we can then claim we freed Venezuelans so they could rule themselves? And what happens if Venezuelans from Communes and communities across the country say no? What happens if they dare to refuse our orders? If they withhold labor in a mass strike? If they surround their occupied “White House,” (called Miraflores)? If they turn off its electricity and water until the U.S. officials leave? Boots on the ground? Bodies buried?

And what about abroad and particularly in the U.S.? So far the international consensus seems to uphold international law. But who says to Trump, return Maduro? Who says to Trump, your motives are vile imperial greed and boundless power? And in the land of the free and home of the brave what if Americans decide to collectively surround wherever the kidnapped Maduro is held to demand his release? And what if support rallies and marches and sit-ins demand peace? What if they challenge mainstream media? They “Press the press.” What if they challenge oil companies? They demand ecological sanity. And of course, what if they challenge the government?

So we again encounter Trumpian worst times stuff. How about news of some offsetting best times stuff? I did not see Mamdani’s mayoral inauguration live on New Year’s Day. But I did see it on Youtube January 2nd. And speaking for myself, the various speakers were all predictably good—until Mamdani. He was more than predictably good. Indeed, to my eyes and ears he was what is sometimes called the real deal.

Suppose you were being sworn in as Mayor of New York, What would be the best possible speech you might sensibly deliver in the economic capital of the Western world? The exploitative center of capitalist greed. Not the best conceivable words for posterity. No, the best words in the freezing cold outside Gracie Mansion in the current Trump-poisoned U.S.A.? What would be the best words that you could deliver to communicate constructively with a massive and incredibly diverse audience in the city and beyond?

I thought about those questions, and about Mamdani’s effort, and I doubt many if any others could have communicated better than Mamdani did. Both in substance and in delivery. So I watched and I found myself tearing up joyfully over and over. I felt seriously hopeful. And I didn’t conjure the hope I felt from my own abstract beliefs, or from long-term carefully cultivated confidence. I felt rising hope and desire too despite the unbelievably corrupt, corrupting, violent, and debilitating world around us all because Mamdani exuded and produced hope plus desire and also, most important, resolve.

Watch the events yourself. Hear his aims which go way beyond immediate policies to embrace long term reconstruction. Listen to his attitude to delivering real action rather than testing where the wind is blowing and perpetually pronouncing “no, that’s impossible” about every significant suggestion. His message, instead was Another world is possible. Help win it.

So, what now? It’s simple enough. Oppose Trump. Go multi issue. Go multi tactic. Resist to stop Trump now and long march toward winning fundamental political, cultural, gender, economic, internationalist, and ecological change as soon as we can. Every day delayed is more pain and suffering, more death and destruction endured.

Reports I have seen say that Maduro has been taken to New York City to be tried, to be found guilty, and to be punished. Trumpian law ascendant. Is NY as the destination a coincidence? Can you hear Trump: Take him to NYC, bellows Trump. Let’s see how Mamdani reacts to that, guffaws Trump. Watch how the aroused and eager for change people of New York react to that, Trump threatens.

Okay, how about if we react with resistance. We react with demonstrations that surround the courtroom where Maduro is held. How about if activists hold signs that read Free Maduro Back to Venezuela on one side, and Try Trump for Crimes Against Humanity on the other side? How about if the reaction is outraged, informed, non compliance? If the reaction is resistance?

Maduro is not a hero of mine. But Trump is evil incarnate. Trump needs to be removed from office. Trump needs to be sequestered away from living breathing humans. And then, that accomplished, how about if we hold a special election? What a thought. The public gets a say. Because Vance is most assuredly also unworthy.

That perhaps ought to be the end of this short essay, but I have another related thought tugging at my mind. Across the U.S. young people in high schools and especially colleges, are witnessing yet again a level of mendacity, hypocrisy, and violent thuggery that has got to capture their attention. They can’t be oblivious, can they? So what will they make of it? What will they do about it? I think for them this may prove to be a life-defining moment. Succumb or rebel? There is a poem by Langston Hughes that goes like this:

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

What keeps running through my head regarding what’s going on, is a question. What will happen to a young person who sees Trump’s vile egomaniacal self unleash the dogs of war? If their reaction sags like a heavy load, I fear their humanity may be downsized for a long time. And if their reaction is instead to dream anew, to imagine better, and to explode, I think the world may change.

Out of the schools and into the streets.The times certainly do need to change.

Opinion: Trump, Venezuela, China, and many long-term problems coming

By Paul Wallis

EDITOR AT LARGE

DIGITAL JOURNAL

January 3, 2026

Fire is seen at Fuerte Tiuna, Venezuela's largest military complex, after a series of explosions in Caracas today. STR / © AFP via Getty Images

The Trump administration’s strike on Venezuela has given the US a new bog in which to get bogged down. Whatever you may think of Maduro’s legitimacy or a 2020 indictment against him in New York, this was a strike on a sovereign nation.

The legality of this action is dubious at best. The US is not at war with Venezuela, but it effectively committed an act of war. Given Trump’s comments about Canada, Greenland, and other global extremely sore points, nobody is impressed.

Trump now says the US will “run” Venezuela and exploit its oil reserves. This approach seems to indicate that the administration seriously thinks it can run another country while totally, almost fatally, mismanaging its own. There are 28 million people in Venezuela, with an estimated 6.8 million expatriates. How will this nation be “run”? Specifically, by whom, under what agenda?

Simultaneously, yet another collision course with China is in process. The US sanctioned four Chinese tankers earlier this week. A Chinese delegation was in Venezuela and had met with Maduro prior to the US attack and is still there. China’s presence in the oil market alone, let alone its very large South American trade ties, should be enough of a caveat to indicate the downside of the US move. China cannot ignore this.

US intervention in Latin and South America has a truly unique record of abject 100% total failure. Regime changes in particular have been catastrophic for the countries affected and totally unproductive for the US. This is certain to be another disaster.

That’s the good news.

The less good news is that the US has taken on yet another open-ended commitment to involvement in yet another continent. The military cost alone is staggering.

The expenditure on these fantasies is likely to be disastrous. The US is effectively broke. Trade revenue is generating false and in fact ridiculous revenue numbers through tariffs. The tariffs are effectively shrinking trade and domestic commerce exponentially.

Add to this building a theme park in Gaza on the ruins of people’s homes.

Add a crusade in Nigeria.

Add Taiwan.

Add a significant risk of potential conflict with Iran.

Add antagonizing NATO and destroying US credibility in futile “negotiations” about Ukraine and open-ended, incredibly vague, commitments there as well.

Add antagonizing Canada and Mexico to the extent of major trade and diplomatic shifts away from the US.

Looking great, isn’t it?

Now add America’s hellish, crashing domestic economy, healthcare, and cost of living.

Now add the fact that Trump will be gone, one way or another, in a very short, if unsightly, time frame. America will be stuck with this situation for years to come.

Pretty high price and long sentence for pandering to a lame-ass fruit fly with the life expectancy of a Dorito, isn’t it?

Never mind the clumsy media-visible positioning.

The reality is pure, expensive, chaos.

_________________________________________________________________

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this Op-Ed are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Digital Journal or its members.

From Öcalan To Maduro: On Imperialisms Logic Of Hostage-Taking

Imperialism has never limited itself solely to military occupations, economic plunder, or diplomatic bullying. Its true power lies in its ability to construct mental and political mechanisms that paralyze the historical will of peoples.

Since the last quarter of the twentieth century, modern capitalist hegemony has centralized a more refined, insidious, and “extralegal but in the name of law” method to overcome the costs and legitimacy crises of classical colonialism: the taking of leaders who represent the hope of freedom as hostages.

This hostage-taking is not merely a physical liquidation; on the contrary, it is a multi layered regime of captivity aimed at targeting collective memory, humiliating collective will, and breaking a people’s self-confidence. In this context, captivity is not a punishment for modern imperialism, but a technique of governance.

The Hegelian master-slave dialectic transcends its classical form here and is carried to a collective plane. The master no longer chains only the individual slave, but also the slave s capacity to dream, their claim to historical continuity, and their vision for the future.

The captured leader ceases to be a mere body; they become the symbolic carrier of a people’s possible futures. Precisely for this reason, the imperialist mind does not judge these leaders, engage in polemics with them, or attempt to persuade them. It casts them outside the law, abducts them through piracy, criminalizes them, and thereby attempts to declare the political line they represent as illegitimate. Here, the discourse of law, human rights, and democracy turns into an ideological smokescreen covering imperialist violence.

While international law is operated as a set of norms that bind only the weak, lawlessness becomes a strategic privilege for imperialist centers. Abduction, illegal transfer, arbitrary detention, and character assassination are the practical tools of this privilege. Therefore, imperialism does not seek to defeat its rivals; it seeks to “pollute” them morally and politically.

Labels such as “terrorist,” “narco-terrorist,” or “dictator” function as ideological weapons rather than substantive criminal charges. The purpose of these labels is to push all social strata associated with the leader into an indefensible, silenced, and isolated position.

This strategy demonstrates that imperialism acts with a systematic, rather than accidental, logic. Hostage-taking is the most refined form of modern colonialism because it eliminates the need for occupation; it aims to produce surrender without awakening the reflex of resistance that tanks would trigger.

The capture of a leader is a message etched into the collective subconscious: “Look, the will you thought represented you is helpless.” In this respect, hostage operations

are not just political but deep psychological warfare techniques.

Precisely at this point, the international conspiracy carried out against Kurdish Leader Abdullah c lan on February 15, 1999, should be read as the laboratory of modern imperialism.

This event was not an isolated violation of law, but an open confession of what means the hegemonic system deems legitimate to protect itself. This pirate coalition, led by the CIA and MOSSAD with the involvement of European intelligence services, aimed to take hostage not just an individual, but the Kurdish people s claim to freedom.

The process stretching from Nairobi to Imrali is the permanentization of a “state of exception” in the sense described by Carl Schmitt. This state of exception reveals who the true sovereign is; the one who holds the power to suspend the law is the actual sovereign.

The February 15 conspiracy showed that the sovereignty of nation-states has long been eroded, and true sovereignty is now concentrated in global intelligence networks and imperialist centers. In this sense, c lan s captivity holds a universal lesson for all oppressed peoples: Imperialism views every thought, every paradigm, and every collective will that produces an alternative to itself as a potential threat and knows no limits in neutralizing this threat.

However, dialectical thought refuses to read this picture as one-sided. Captivity does not always mean absolute defeat. On the contrary, with a correct historical and ideological positioning, it can transform into a new moment of liberation. This is where imperialism s greatest miscalculation lies. The intellectual production developed by c lan under conditions of heavy isolation in Imrali transformed the place of captivity into an arena for a revolution of the mind.

While imperialism chained the body, it failed to calculate the capacity of thought to become socialized. This situation demonstrated that the strategy of hostage-taking is not absolute; rather, it can be neutralized through a revolutionary line. Today, the operation targeting President Maduro and his spouse in Venezuela involving abduction and forced transfer to the USA is a contemporary manifestation of this historical continuity.

This is not an act of personal revenge; it is an attempt to symbolically liquidate a political line in Latin America that refuses to bow to imperialism. US economic sanctions, diplomatic siege, and character assassination have now moved to a more advanced stage: by piratically taking President Maduro hostage, the Bolivarian revolution has been left leaderless.

The similarities here are not coincidental. There is a methodological and ideological continuity between the isolation imposed on c lan and the threats directed at Maduro. In both cases, the target is a people’s will to self-determination. In both cases, imperialism attempts to legitimize its own piracy through the discourse of “law.” And in both cases, the fundamental question is: Does a revolution collapse when its leader is taken hostage, or does it enter a new historical phase?

The answer to this question compels us to rethink the relationship between the state,

power, society, and freedom. Because the imperialist strategy of hostage-taking is not just an external attack; it is also a litmus test that reveals the internal weaknesses of revolutionary processes. Any revolutionary experiment that is state-centered, bureaucratized, and views the people’s self-organization as secondary becomes excessively dependent on the physical presence of the leader. This dependency makes imperialist conspiracies more effective.

Precisely for this reason, grasping the dialectic of captivity is possible not only by exposing imperialism but by the revolutionary subject reconstructing itself. The international pirate operation of February 15, 1999, should be treated as a threshold that reveals the means by which imperialism reproduces itself, beyond the unlawful detention of a leader.

This event was not just the neutralization of a political actor, but an attempt to suspend the claim of a people to be political subjects on a global scale. The multi national character of the operation was structural, not accidental.

This mechanism showed that nation-state law has been effectively suspended. A leader was captured in a “void” that fell under no country s jurisdiction and was subsequently imprisoned on an island. This situation points to a plane that transcends Giorgio Agamben s concept of “bare life.” What is targeted here is not just biological life, but the capacity to produce political meaning.

Imperialist logic preferred to silence and invisibilize c lan rather than eliminate his physical existence, hoping to neutralize his intellectual line over time. However, this preference worked contrary to the expected result. Captivity paradoxically laid the ground for thought to break away from material bonds and enter a broader social circulation.

The Imrali process must be evaluated as a phenomenon that transcends the logic of classical prisons. The isolation regime established there was built on the fragmentation of language, contact, and temporality. Yet, the intellectual production developed under these conditions evolved into an axis that redefines the relationship between state, power, and society.

The critique of state-centered liberation strategies, the exposure of the historical limits of the nation-state form, and the conception of social organization as an autonomous sphere are the theoretical outputs of this process. The fundamental error of imperialism lay in the assumption that by taking the leader hostage, the idea could also be taken hostage. Yet, in modern political struggles, an idea cannot be reduced to a body. This contradiction is embodied in the transformation of the Kurdish Freedom Movement.

The classical national liberation perspective centered on seizing the state gave way to an approach based on liberating society. This transformation is not just a tactical adaptation but an ontological break. In this sense, February 15 is not an end, but a beginning. The “decapitation” strategy of imperialism ironically contributed to a political model that is no longer leader-centric.

This situation contains an important lesson on how imperialism can be overcome with its own tools. The strategy of hostage-taking can only be effective if the line

represented by the leader has not been socialized. If an idea remains the property of a narrow cadre or a singular figure, it collapses with captivity. But if the idea has become part of the social fabric, captivity makes it more visible. This lesson s universal dimension is even more evident in current developments in Latin America.

The siege of Venezuela is a political will-breaking operation. Targeting Maduro is targeting the Bolivarian process itself. However, a critical difference emerges: The paradigm developed by the Kurdish Freedom Movement after February 15 strengthened the social subject by moving the leader s physical presence away from the center. In Venezuela, the revolutionary process still largely shapes itself around the state apparatus and central power, creating a ground that makes imperialist interventions more effective.

Therefore, the true significance of February 15 is not just a reckoning with the past, but a warning for the present and future. Imperialism changes its methods but not its goals. Freedom depends on the leader s paradigm taking form in social relations.

The trajectory of aggression against Venezuela reveals that imperialism has never seen Latin America as anything more than a “backyard.” Hugo Ch v z s rise made Venezuela an intolerable deviation for the imperialist system. The pressure concentrated on Maduro is the targeting of the line he represents.

The media, as a strategic apparatus, presents the economic crisis as an internal failure, hiding the impact of sanctions. This discourse prepares the ideological ground for the abduction of a leader as “the establishment of justice.” The methods used are nearly identical to the February 15 conspiracy: intense international defamation, diplomatic isolation, and then a pirate operation in the name of the “international community.” This chain is the hallmark of imperialism.

However, dialectical analysis cannot merely expose external pressure. Imperialist interventions are effective when they connect with internal weaknesses. In Venezuela, the revolution s reliance on oil revenues and a redistribution model failed to transform production relations in the long run.

The emergence of a new elite, the “Boliburgues a,” has eroded the moral legitimacy of the revolution. This is where the critique of state-centered socialism becomes inevitable. When the state becomes a sacred carrier of revolution, it risks reducing the idea of freedom to technical management.

The critique of state-centered socialism is not to devalue the Bolivarian process, but to move it to a more sustainable line of freedom. Democratic Confederalism, as a paradigm, seeks not to conquer the state, but to transcend it by strengthening local and horizontal relations. This perspective transforms the understanding of leadership; the leader becomes a catalyst for social will rather than an authority that monopolizes it.

The universal dimension of c lan s paradigm is a general freedom strategy against modern power forms. In Venezuela, if the revolution remains a project of the state, it will always be shaken by external intervention.

But if the revolution takes root in neighborhoods, workplaces, and local councils, there

is no longer a single center to target. Power becomes stronger as it is decentralized. The duty of revolutionaries is not just to defend Maduro, but to transform the resistance he represents into the daily practice of the people.

International solidarity must also transcend symbolic support. The line drawn between the Middle East and Latin America is a historical necessity. The Kurdish struggle and the Venezuelan resistance must be linked through a common paradigm of freedom. Internationalism is a vital need. Revolutionary action is about creating alternatives and organizing life itself. If this task is undertaken, no CIA-MOSSAD operation or pirate scenario from the USA can stop the march of peoples toward freedom.

No comments:

Post a Comment