“Public power” organizers are pushing for democratized control and truly public ownership of our energy system.

By Derek Seidman ,

January 2, 2026

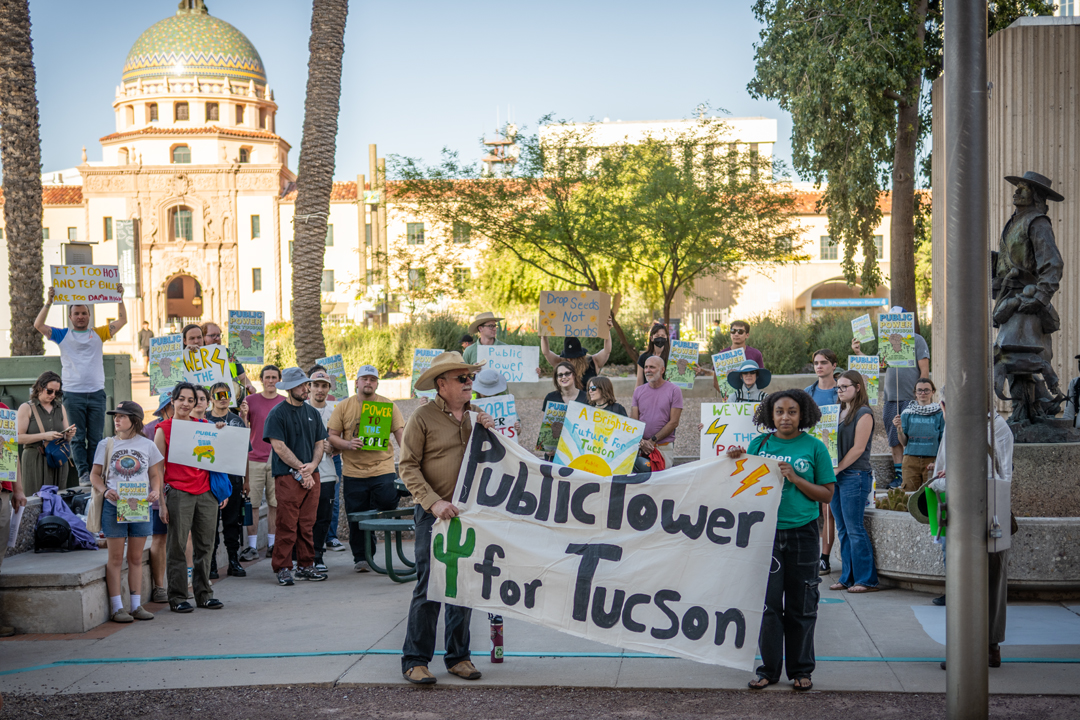

Community members rally at Tucson City Hall.Cameron Capara

Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

Electricity bills for millions of utility customers are skyrocketing across the U.S. while the number of households facing extreme utility debt is mounting. Energy costs are being turbocharged by the AI data center boom, which is prolonging the burning of fossil fuels in the face of intensifying climate chaos. Overseeing all this is a powerful regime of investor-owned utilities that dominate our energy system. These for-profit corporations own and control the basic infrastructure we all depend on. Their executives and shareholders profit by raising electric rates or skimping on maintenance. And now, private equity firms are gunning for utilities.

But over the past few years, a vibrant movement for public power has emerged and grown.

Public power means public ownership and democratic control of our energy system. It’s an alternative to corporate-owned, profit-driven utilities. Public utilities in the U.S. are not new, and recent campaigns — from Tucson to Milwaukee, from San Diego to Ann Arbor — seek to expand and improve on this precedent, creating a truly democratic public utility system that serves human needs over profits. A notable victory for public power came with the 2023 passage of New York’s Build Public Renewables Act, and a campaign for public power in New York’s Hudson Valley has been gaining momentum.

Public power means public ownership and democratic control of our energy system. It’s an alternative to corporate-owned, profit-driven utilities.

This Truthout roundtable explores what public power means and why it’s needed, how it intersects with other issues and struggles, organizing lessons from ongoing campaigns, and more. Lee Ziesche is a climate justice organizer, co-chair of the Tucson Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), and a core organizer in Tucson’s public power campaign. She was also involved in Public Power NY’s successful campaign to pass the Build Public Renewables Act. Matt Sehrsweeney is a climate justice organizer and Metro DC DSA member who co-chairs We Power DC, Washington, D.C.’s campaign for public power. Sandeep Vaheesan is the author of the recently published book Democracy in Power: A History of Electrification in the United States and the legal director at the Open Markets Institute.

This roundtable has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Derek Seidman: What is public power? Why’s it worth fighting for?

Matt Sehrsweeney: The priorities of investor-owned utilities (IOUs) are fundamentally at odds with those of rate payers. IOUs are obligated to maximize their profits for their shareholders, which usually means raising rates as high as possible. Operating a crucial service like providing electricity as a profit-seeking business leads to terrible outcomes for rate payers. In D.C., nearly a quarter of households are in debt to Pepco, their utility.

Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

Electricity bills for millions of utility customers are skyrocketing across the U.S. while the number of households facing extreme utility debt is mounting. Energy costs are being turbocharged by the AI data center boom, which is prolonging the burning of fossil fuels in the face of intensifying climate chaos. Overseeing all this is a powerful regime of investor-owned utilities that dominate our energy system. These for-profit corporations own and control the basic infrastructure we all depend on. Their executives and shareholders profit by raising electric rates or skimping on maintenance. And now, private equity firms are gunning for utilities.

But over the past few years, a vibrant movement for public power has emerged and grown.

Public power means public ownership and democratic control of our energy system. It’s an alternative to corporate-owned, profit-driven utilities. Public utilities in the U.S. are not new, and recent campaigns — from Tucson to Milwaukee, from San Diego to Ann Arbor — seek to expand and improve on this precedent, creating a truly democratic public utility system that serves human needs over profits. A notable victory for public power came with the 2023 passage of New York’s Build Public Renewables Act, and a campaign for public power in New York’s Hudson Valley has been gaining momentum.

Public power means public ownership and democratic control of our energy system. It’s an alternative to corporate-owned, profit-driven utilities.

This Truthout roundtable explores what public power means and why it’s needed, how it intersects with other issues and struggles, organizing lessons from ongoing campaigns, and more. Lee Ziesche is a climate justice organizer, co-chair of the Tucson Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), and a core organizer in Tucson’s public power campaign. She was also involved in Public Power NY’s successful campaign to pass the Build Public Renewables Act. Matt Sehrsweeney is a climate justice organizer and Metro DC DSA member who co-chairs We Power DC, Washington, D.C.’s campaign for public power. Sandeep Vaheesan is the author of the recently published book Democracy in Power: A History of Electrification in the United States and the legal director at the Open Markets Institute.

This roundtable has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Derek Seidman: What is public power? Why’s it worth fighting for?

Matt Sehrsweeney: The priorities of investor-owned utilities (IOUs) are fundamentally at odds with those of rate payers. IOUs are obligated to maximize their profits for their shareholders, which usually means raising rates as high as possible. Operating a crucial service like providing electricity as a profit-seeking business leads to terrible outcomes for rate payers. In D.C., nearly a quarter of households are in debt to Pepco, their utility.

We Power DC organizers put up posters to spread the word about their campaign.

Matt Sehrsweeney

Publicly owned and operated utilities, on the other hand, are more accountable to the needs of communities and can better prioritize things like more affordable rates and reliable service. There’s also IOUs’ reliance on fossil fuels. If we want to address the climate crisis at the speed that is necessary, we need utilities that are responsive to climate goals.

Sandeep Vaheesan: Electricity is an essential service. It’s hard to imagine modern life without electricity. Given this, it’s quite odd that the financial sector and shareholders have so much power over our electricity. In the U.S., about three out of four power customers are served by an investor-owned utility. These private monopolies prioritize profits, which is antithetical to high quality, affordable, and clean electric service.

Public power offers a more promising path where public service is truly front and center. Publicly owned utilities are focused on high quality, affordable, and sustainable electricity. They’re not pressured to deliver big profits to shareholders. Public power also offers community control over things like rate design and infrastructure siting and ways to get to net zero. Public power offers the promise of bringing a more systemic, holistic approach to decarbonization.

Why is public power a core struggle for the left specifically?

Lee Ziesche: Public power is a way to actually improve the lives of working-class people. Electric bills are absurd. People are racking up debt. This is a chance to show people that socialism can work. We’ve talked to many people who aren’t socialists but whose bills are so high that they’re ready to support a socialist solution. We can prove that a public good can serve the people and be more affordable.

It makes no sense that profit-seeking corporations own the poles and wires that bring electricity into our homes. People need electricity to survive, especially in places like Tucson, where we have extreme heat. It should be a public good. That’s what public power is all about.

Sehrsweeney: These campaigns also represent an attempt to expand small-d democracy in our everyday lives. It’s about enhancing local democratic control over everyday institutions that provide basic public services. Expanding democracy is a huge part of the project of the left.

What are some important lessons you’ve learned from campaigning for public power?

Sehrsweeney: Harnessing peoples’ latent anger against utilities is crucial. People are fed up with rising electricity bills. Here in D.C., we’ve seen Pepco’s profits skyrocket. People are pissed off. Capitalizing on that anger has been a key part of our campaign.

“It’s not a natural fact of life that our bills have to go way up. Our government should be intervening to prevent these rate hikes.”

Politicizing rate hikes has been an entry point for getting people involved. It’s not a natural fact of life that our bills have to go way up. Our government should be intervening to prevent these rate hikes. We’ve pressed regulators and politicians to do their job. Rate hikes have been an important organizing site for us.

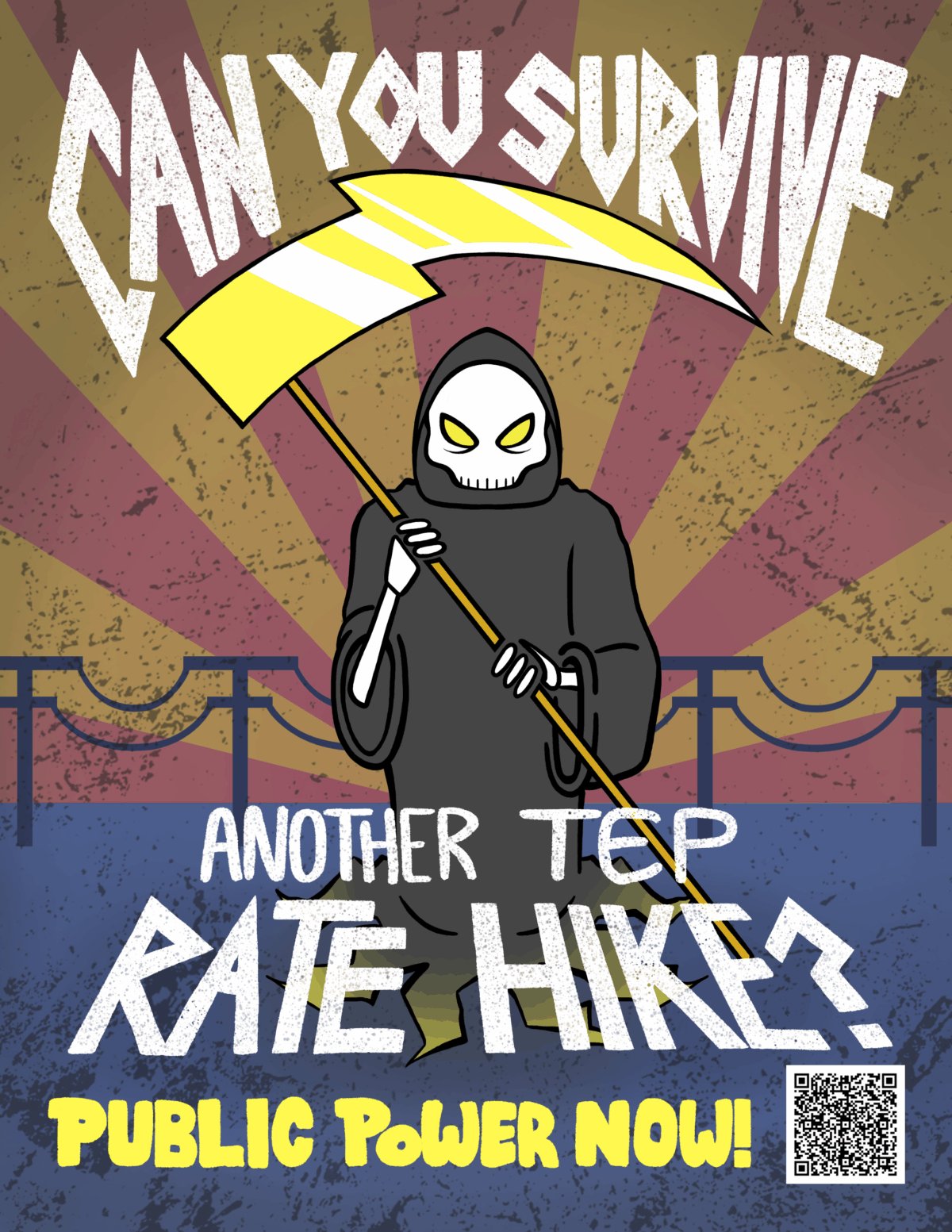

Ziesche: We’re also doing that in Tucson. Tucson Electric Power (TEP) filed for another rate hike this summer, so we put up posters around town featuring a grim reaper that say “Will you survive another TEP rate hike?”

Publicly owned and operated utilities, on the other hand, are more accountable to the needs of communities and can better prioritize things like more affordable rates and reliable service. There’s also IOUs’ reliance on fossil fuels. If we want to address the climate crisis at the speed that is necessary, we need utilities that are responsive to climate goals.

Sandeep Vaheesan: Electricity is an essential service. It’s hard to imagine modern life without electricity. Given this, it’s quite odd that the financial sector and shareholders have so much power over our electricity. In the U.S., about three out of four power customers are served by an investor-owned utility. These private monopolies prioritize profits, which is antithetical to high quality, affordable, and clean electric service.

Public power offers a more promising path where public service is truly front and center. Publicly owned utilities are focused on high quality, affordable, and sustainable electricity. They’re not pressured to deliver big profits to shareholders. Public power also offers community control over things like rate design and infrastructure siting and ways to get to net zero. Public power offers the promise of bringing a more systemic, holistic approach to decarbonization.

Why is public power a core struggle for the left specifically?

Lee Ziesche: Public power is a way to actually improve the lives of working-class people. Electric bills are absurd. People are racking up debt. This is a chance to show people that socialism can work. We’ve talked to many people who aren’t socialists but whose bills are so high that they’re ready to support a socialist solution. We can prove that a public good can serve the people and be more affordable.

It makes no sense that profit-seeking corporations own the poles and wires that bring electricity into our homes. People need electricity to survive, especially in places like Tucson, where we have extreme heat. It should be a public good. That’s what public power is all about.

Sehrsweeney: These campaigns also represent an attempt to expand small-d democracy in our everyday lives. It’s about enhancing local democratic control over everyday institutions that provide basic public services. Expanding democracy is a huge part of the project of the left.

What are some important lessons you’ve learned from campaigning for public power?

Sehrsweeney: Harnessing peoples’ latent anger against utilities is crucial. People are fed up with rising electricity bills. Here in D.C., we’ve seen Pepco’s profits skyrocket. People are pissed off. Capitalizing on that anger has been a key part of our campaign.

“It’s not a natural fact of life that our bills have to go way up. Our government should be intervening to prevent these rate hikes.”

Politicizing rate hikes has been an entry point for getting people involved. It’s not a natural fact of life that our bills have to go way up. Our government should be intervening to prevent these rate hikes. We’ve pressed regulators and politicians to do their job. Rate hikes have been an important organizing site for us.

Ziesche: We’re also doing that in Tucson. Tucson Electric Power (TEP) filed for another rate hike this summer, so we put up posters around town featuring a grim reaper that say “Will you survive another TEP rate hike?”

Poster designed by Trisha Smith

Be prepared to talk to a lot of people about their electric bills. Anytime there’s a major festival we’re out talking to people or asking them to sign a petition.

You should also be ready to make politicians a little uncomfortable. You have to build the power to challenge them and, if necessary, primary politicians who aren’t on board. DSA chapters waged multiple primary challenges across New York State, and we’ve done the same here in Tucson. When we were out door-knocking for Sadie Shaw, we also talked about public power. Our politicians often have cozy relationships with these powerful utilities. You need to build a big enough base to get elected officials on your side.

The public power campaign in New York was really impressive. What lessons did you take from it?

Ziesche: We built a huge statewide coalition that reflected all of New York to win the Build Public Renewables Act. A lot of the organizing originated from DSA chapters, and we got environmental justice groups and labor on board. We really built a massive movement. Thousands of people did things like submitting comments or calling the governor when we needed it.

We primaried elected officials and also challenged them in creative ways that made them incredibly uncomfortable. We made gigantic Venmo boards showing the donations that elected officials received from utilities or fossil fuel companies.

Can you talk about how the fight for public power intersects with struggles for racial and housing justice?

Sehrsweeney: In D.C., the parts of the city hardest hit by rising electricity prices and energy shut offs are predominantly Black, poor and working-class wards. Over 50 percent of Pepco’s low-income customers are in utility debt. The burden of energy injustice falls most acutely on Black and Brown communities and people facing housing insecurity. The folks most likely to be evicted are also the folks most likely to face energy shut offs.

Ziesche: Our public power campaign in Tucson merged this summer with a fight against a massive Amazon data center. Our city voted against it, but TEP is moving forward with it anyway. We know that Amazon Web Services works with Palantir to target immigrants. We have this potential monster being built in the Sonoran desert where we have almost no water. This will send our electricity through the roof and could be used to target immigrants in our community. [Note: Since this interview was conducted, Amazon pulled out of the data center project, though developers are still trying to advance it.]

Be prepared to talk to a lot of people about their electric bills. Anytime there’s a major festival we’re out talking to people or asking them to sign a petition.

You should also be ready to make politicians a little uncomfortable. You have to build the power to challenge them and, if necessary, primary politicians who aren’t on board. DSA chapters waged multiple primary challenges across New York State, and we’ve done the same here in Tucson. When we were out door-knocking for Sadie Shaw, we also talked about public power. Our politicians often have cozy relationships with these powerful utilities. You need to build a big enough base to get elected officials on your side.

The public power campaign in New York was really impressive. What lessons did you take from it?

Ziesche: We built a huge statewide coalition that reflected all of New York to win the Build Public Renewables Act. A lot of the organizing originated from DSA chapters, and we got environmental justice groups and labor on board. We really built a massive movement. Thousands of people did things like submitting comments or calling the governor when we needed it.

We primaried elected officials and also challenged them in creative ways that made them incredibly uncomfortable. We made gigantic Venmo boards showing the donations that elected officials received from utilities or fossil fuel companies.

Can you talk about how the fight for public power intersects with struggles for racial and housing justice?

Sehrsweeney: In D.C., the parts of the city hardest hit by rising electricity prices and energy shut offs are predominantly Black, poor and working-class wards. Over 50 percent of Pepco’s low-income customers are in utility debt. The burden of energy injustice falls most acutely on Black and Brown communities and people facing housing insecurity. The folks most likely to be evicted are also the folks most likely to face energy shut offs.

Ziesche: Our public power campaign in Tucson merged this summer with a fight against a massive Amazon data center. Our city voted against it, but TEP is moving forward with it anyway. We know that Amazon Web Services works with Palantir to target immigrants. We have this potential monster being built in the Sonoran desert where we have almost no water. This will send our electricity through the roof and could be used to target immigrants in our community. [Note: Since this interview was conducted, Amazon pulled out of the data center project, though developers are still trying to advance it.]

Community members march to Tucson Electric Power headquarters in downtown Tucson, Arizona. Cameron Capara

We’ve also done multiple events with the Tucson Tenants Union. They have members who lose housing because they can’t afford their electric bills. Overall, we’re trying to approach our organizing more like a tenants union. How do we actually build enough power together as customers? If TEP won’t sell us back our grid at a fair price, maybe the people of Tucson can go on a bill strike and collectively stop paying our bills.

What about public power campaigns and the labor movement?

Vaheesan: The relationship between labor and public power campaigns is tricky and challenging. Most unionized workers in the power sector are represented by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), which tends to have a more conservative outlook that doesn’t necessarily embrace alternative forms of ownership. In the U.S. today, it’s also better to be a member of a private sector union than a public sector union, which often have no right to strike and now have a harder time collecting dues.

But I think these challenges can be overcome. Investor-owned utilities are under shareholder pressure to increase profits through rate hikes and cutting costs. This will become more acute as private equity enters the utility industry on a large scale. They are going to cut wages and benefits and rely more on outside contractors. The good wages and benefits that many power industry workers have long enjoyed are poised to change.

There’s an opportunity for public power campaigners to make the case to unions that public ownership shouldn’t be seen as a threat. Public power can actually be a way of maintaining and even improving the standards for workers and their unions. Further, public ownership offers the opportunity for real economic democracy, where not only communities, but the workers of the utility themselves, have a say in how the enterprise is run.

Ziesche: In New York, getting labor, especially the IBEW, to a neutral position was important, and they actually now support building renewable public energy. You need to figure out how to structure your campaign and public utilities to not hurt labor.

What are some major challenges you’ve faced? What do you wish you knew when you started out organizing that you know now?

Sehrsweeney: The goal of public power can also feel unattainably large. So you need to break things down into steps toward long-term goals. Maybe that’s opposing a data center or organizing against a rate hike. Building towards long term goals with reforms that put power back into the hands of the people is crucial.

We’ve also done multiple events with the Tucson Tenants Union. They have members who lose housing because they can’t afford their electric bills. Overall, we’re trying to approach our organizing more like a tenants union. How do we actually build enough power together as customers? If TEP won’t sell us back our grid at a fair price, maybe the people of Tucson can go on a bill strike and collectively stop paying our bills.

What about public power campaigns and the labor movement?

Vaheesan: The relationship between labor and public power campaigns is tricky and challenging. Most unionized workers in the power sector are represented by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), which tends to have a more conservative outlook that doesn’t necessarily embrace alternative forms of ownership. In the U.S. today, it’s also better to be a member of a private sector union than a public sector union, which often have no right to strike and now have a harder time collecting dues.

But I think these challenges can be overcome. Investor-owned utilities are under shareholder pressure to increase profits through rate hikes and cutting costs. This will become more acute as private equity enters the utility industry on a large scale. They are going to cut wages and benefits and rely more on outside contractors. The good wages and benefits that many power industry workers have long enjoyed are poised to change.

There’s an opportunity for public power campaigners to make the case to unions that public ownership shouldn’t be seen as a threat. Public power can actually be a way of maintaining and even improving the standards for workers and their unions. Further, public ownership offers the opportunity for real economic democracy, where not only communities, but the workers of the utility themselves, have a say in how the enterprise is run.

Ziesche: In New York, getting labor, especially the IBEW, to a neutral position was important, and they actually now support building renewable public energy. You need to figure out how to structure your campaign and public utilities to not hurt labor.

What are some major challenges you’ve faced? What do you wish you knew when you started out organizing that you know now?

Sehrsweeney: The goal of public power can also feel unattainably large. So you need to break things down into steps toward long-term goals. Maybe that’s opposing a data center or organizing against a rate hike. Building towards long term goals with reforms that put power back into the hands of the people is crucial.

We Power DC organizers set up a table at a community event to talk to neighbors about their issues with Pepco, Washington, D.C.’s electric utility.

Matt Sehrsweeney

Figuring out how to translate these wonky issues into something that people can understand is also important. Be prepared to talk to people about their utility bills, because that’s one of the best entry points. We recently produced a white paper report on municipalization in D.C. that goes through how Pepco has failed people and has recommendations on how a public utility would be better. This study built our credibility and made legislators take us more seriously. It’s also been a good political education tool for our coalition partners and for lawmakers.

Ziesche: We are 100 percent volunteer-run, so building the capacity to take on a gigantic corporation is a challenge. We have to be our own experts and do our own research. It’s also a challenge to get taken seriously when you’re first starting out. Public power seems like a radical thing to some people. But this is actually the common sense solution. You need to explain that.

Vaheesan: The resource issue is a major obstacle to successful public power efforts, which entail taking on some of the most powerful corporate interests. On one side, you have investor-owned utilities with tens of millions of dollars to spend against municipalization, and on the other side you have a small group of hard working, dedicated volunteers who are also badly outgunned.

Also, power systems are complex and highly technical. There’s a lot of jargon. It’s easy for investor-owned utilities to say this is simply too hard for ordinary people to understand. We saw this in Maine in 2023. We need to hammer home that public utilities are a well-established institutional form. Around 54 million people in the U.S. get their electricity from publicly owned utilities. When you factor in consumer-oriented rural electric cooperatives, you’re talking about 100 million people. It’s a proven model, and we need to keep repeating that.

What’s making you feel hopeful or optimistic right now?

Sehrsweeney: At a time when the federal landscape for climate policy is so bleak, it makes sense for organizers to focus locally. Also, in addition to promoting energy justice, the fight for public power advances democracy by putting power into the hands of regular people and bringing them into the democratic project.

Vaheesan: I feel a renewed sense of possibility because of what’s happening in places like D.C. and Tucson and the mid-Hudson Valley. After many decades, public power is on the agenda again. This is a real moment of opportunity to push for public power at the state and local level and to lay the groundwork for eventual federal support. The energy affordability issue is not going away. Rate increases of 15 percent or 20 percent are becoming common. If we’re serious about energy justice and affordable rates, building public power is really the only way forward.

Figuring out how to translate these wonky issues into something that people can understand is also important. Be prepared to talk to people about their utility bills, because that’s one of the best entry points. We recently produced a white paper report on municipalization in D.C. that goes through how Pepco has failed people and has recommendations on how a public utility would be better. This study built our credibility and made legislators take us more seriously. It’s also been a good political education tool for our coalition partners and for lawmakers.

Ziesche: We are 100 percent volunteer-run, so building the capacity to take on a gigantic corporation is a challenge. We have to be our own experts and do our own research. It’s also a challenge to get taken seriously when you’re first starting out. Public power seems like a radical thing to some people. But this is actually the common sense solution. You need to explain that.

Vaheesan: The resource issue is a major obstacle to successful public power efforts, which entail taking on some of the most powerful corporate interests. On one side, you have investor-owned utilities with tens of millions of dollars to spend against municipalization, and on the other side you have a small group of hard working, dedicated volunteers who are also badly outgunned.

Also, power systems are complex and highly technical. There’s a lot of jargon. It’s easy for investor-owned utilities to say this is simply too hard for ordinary people to understand. We saw this in Maine in 2023. We need to hammer home that public utilities are a well-established institutional form. Around 54 million people in the U.S. get their electricity from publicly owned utilities. When you factor in consumer-oriented rural electric cooperatives, you’re talking about 100 million people. It’s a proven model, and we need to keep repeating that.

What’s making you feel hopeful or optimistic right now?

Sehrsweeney: At a time when the federal landscape for climate policy is so bleak, it makes sense for organizers to focus locally. Also, in addition to promoting energy justice, the fight for public power advances democracy by putting power into the hands of regular people and bringing them into the democratic project.

Vaheesan: I feel a renewed sense of possibility because of what’s happening in places like D.C. and Tucson and the mid-Hudson Valley. After many decades, public power is on the agenda again. This is a real moment of opportunity to push for public power at the state and local level and to lay the groundwork for eventual federal support. The energy affordability issue is not going away. Rate increases of 15 percent or 20 percent are becoming common. If we’re serious about energy justice and affordable rates, building public power is really the only way forward.

Tucson community members rally on Earth Day for public power after feasibility study results were released showing a public power utility would save customers hundreds of dollars. Vivek Bharathan

Public power used to be the stuff of popular politics. If we do the organizing, advocacy, and public education now, we could be in a good position in three to five years to push for a major expansion of public power again.

Ziesche: When we’re out there talking to people, they’re so grateful that we’re taking on this fight. Those conversations give me a lot of hope.

Also, those of us waging different public power fights are getting connected nationally as a movement. There’s a new organization, Public Grids, that’s bringing people together. This will help our individual fights. It’s incredibly hard to take on a gigantic corporation, but together we’re showing that the entire system across this country is not working. The unaffordability crisis around electricity is also being supercharged by the massive data center build out. We’re reaching a crisis point. It’s going to be clear to most people that this current system cannot continue.

Public power used to be the stuff of popular politics. If we do the organizing, advocacy, and public education now, we could be in a good position in three to five years to push for a major expansion of public power again.

Ziesche: When we’re out there talking to people, they’re so grateful that we’re taking on this fight. Those conversations give me a lot of hope.

Also, those of us waging different public power fights are getting connected nationally as a movement. There’s a new organization, Public Grids, that’s bringing people together. This will help our individual fights. It’s incredibly hard to take on a gigantic corporation, but together we’re showing that the entire system across this country is not working. The unaffordability crisis around electricity is also being supercharged by the massive data center build out. We’re reaching a crisis point. It’s going to be clear to most people that this current system cannot continue.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

Derek Seidman is a writer, researcher and historian living in Buffalo, New York. He is a regular contributor for Truthout and a contributing writer for LittleSis.

Derek Seidman is a writer, researcher and historian living in Buffalo, New York. He is a regular contributor for Truthout and a contributing writer for LittleSis.

No comments:

Post a Comment