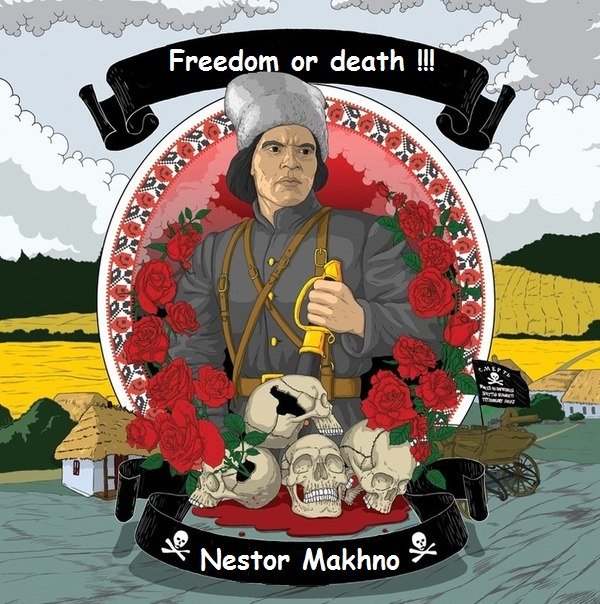

Nestor Makhno: Ukraine’s Anarchist Cossack and the Battle for the Ukraine, 1917-1921

Of the many violent and often grandiose and dramatic revolutionist/reactionary heroes and/or tyrants of the Russian Civil War 1917-1921 perhaps none is as controversial or infamous as the Ukrainian anarchist-peasant turned revolutionary warlord, "Batko" (Father) Nestor Makhno (b.1889-1934).

Nestor Makhno in 1919

The influence and the impact of the greater culture of the irregular guerrilla insurgent and cavalrymen cannot be overstated in regards to the Russian Civil War and its corresponding conflicts from 1917-1923. Though essentially outlaw bandits in some cases, there were some units who were legitimate military forces as well, whether they be ‘Red’, ‘White’, revolutionary or reactionist, anarchist or nationalist, all were a product of Russian culture and the general socio-economic & cultural turmoil of the fall of the old Russian Imperial regime.

Makhno and his anarchist Makhnovist faction were revolutionaries by doctrine and yet they were counter revolutionaries and also anti-reactionary as well. They were anti-monarchy as well as anti-imperialist. Makhno and his men waved the black flag of anarchism, his men fought their oppressed families. For their militant & semi collectivist-anarchist stance alone the Makhnovists were markedly unique amongst the many different armies, movements, and political factions which developed in not just the Ukrainefrom 1917-1920, but in all of corners Russia and central Europe and in partsAsia as well during the same period.

The Early Life of Makhno, Ukraine during & after World War I

A hero and near folk-hero, Nestor Makhno, was born in the year 1889, spending his formative years in the fields of Guliai Pole, Ukraine, then a territory of the Russian Empire as a farmhand and later factory worker. Ukraine in this era was an important part of Russia's economic output, long called the "breadbasket of Eastern Europe", Ukraine had been established on the hard labor of Ukrainians working the vast farm-estates of the Czar's Southern Russian Empire. By the age of 17, Makhno had left for the city at the height of the Revolution of 1905 which would eventually shake the foundation of the old Russian Empire. Russia had lost the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, its people demanding a say in the government and an end to their collective sufferings. Taking to the streets of St. Petersburg in January, the Russian poor & middle class were met by Imperial bullets and Cossack Sabres. Soon after, those who had survived the war would return from the Far East began to and the Revolution petered out.

Having been arrested in 1908 for being a member of a revolutionary/anarchist cell (his service may or may not have entailed assassinating a local politician) Makhno spent eight years in a Moscow prison before his release in 1917 under the political prisoner pardon under the new Provisional Government of Georgy Lvov and later Alexander Kerensky. Makhno left Russia and returned home to the Ukraine an even more hardened revolutionary and anarchist that he had been in 1905. Returning to Gulia Pole, Makhno must have been surprised to see that his hometown had now become a hotbed for revolutionary activity. Even before the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 which allowed the Austro-German armies into the Ukraine as occupiers, Makhno had organized peasant unions to protect and punish the hated landowning kulaks. The kulaks, many of whom were German Mennonites loyal to the Czar or the Austro-Hungarians were most hated by the ethnic Ukrainians because of their societal status and at times poor treatment of Ukrainian farmers during the 18th and early 19th centuries. Other Mennonite farmers and settlers were the targets of revolutionary and anti-revolutionary reprisals including atrocities committed by Makhno's army.

Ukraine 1919

Immediately after Brest-Litovsk, Pavlo Skoropadsky (b.1873-1945), a former Tsarist cavalry officer was installed as Hetman, a military warlord/puppet regime figurehead of occupied Ukraine. A German by birth and a veteran of Russo-Japanese War and the Great War, Skoropadsky formed the Ukrainian National Union in March of 1918, fleeing in December of that year after the Central Powers collapsed in November.

The Black Flag Rises: Makhno and the Battle for Ukraine

Makhno raised the black flags of the Revolutionary Insurrectionist Army in the spring and summer of 1918 when German Hetman puppet government still controlled part of the Ukraine with the partial military support of German heer. Though young and by no means a proven military commander in even a modest sense, armed men had begun to flock to the young but charismatic and brave Makhno. In the skirmish near the Dibrivki Forest, Makhno earned the title Batko (Ukrainian for father: in this meaning the literal father of the insurrectionist army itself) for his heroic, inspired, and seemingly fearless & improbable victory over a 1,000 strong kulak militia armed and supported by hated the Austro-German occupiers. Rallying his small force of 30 men or more, they rushed the enemy shooting and cutting their way through their lines in a fierce charge.

Makhno and his officers during the War

With their leader at the front the Makhnovists killed perhaps hundreds of kulaks during the violent charge and subsequent retreat, riding them down in the rout and slaughtering them, the battle ending with the drowning of the survivors by angry local peasants who had now joined the insurrection of Batko Makhno.

The Ukrainian Socialist Republic had also been declared by this point, with the Russians preparing Red Army and Red Guard units from the North for an expedition south. Their primary objective was to defeat the White army of Lt. General Anton Denikin occupying Ukraine in 1919.

Later the new nationalist minded Polish Republic under Jozef Pilsuduski attacked the Ukraine capturing Kiev for a brief time, inadvertently starting the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-1921. Poland captured Western Ukraine for a time following their victory but an eventual stalemate ensues, ending with Poland's stunning victory on the Vistula in 1920. Makhno took advantage of the chaos and the complexity of the multi-sided conflict being fought around him to wage his own war on all those who he felt opposed the peasants of Ukraine. His Makhnovists burned estates, bourgeois mansions, and tge farms of the rich German kulaks or the Russian overlords who had oppressed peasant Ukranians for years, in some cases stripping opulent country houses and estates bare of their provisions and extravagances.

Though unfounded Soviet propaganda later attributed anti-Semitic violence to the Makhnovists which had been most likely committed by reactionary White forces or by apolitical bandit or reactionary groups. Makhno never condoned such killings but may have secretly or unknowingly perpetrated massacres against Jewish, Mennonite, or other minority communities in the Ukraine. Counter revolutionaries and especially Tsarist (White) officers were almost never spared however and no mercy was given or received. Makhno even killed Tsarist officers himself in summary executions with his sabre.

Makhnovist Army, c.1919

Makhnovists staged raids and ambushes everywhere capturing White army munitions and supplies, killing and harassing any Tsarist-Monarchist army forces they could find in ambushes and raids-weakening the White grasp on the Ukraine before their total collapse in the Fall of 1920. Makhno’s first great enemy was the White general Anton Denikin (b.1872-1947) who was constantly at war with Makhno, overextending his supplies and manpower fighting a brutal insurrection against the Makhnovists while attempting to launch a campaign to take Moscow from the Bolsheviks.

Lieutenant-General Denikin, decorated for his service in the Brusilov Offensive of 1916 which had been fought in parts of the Ukraine during World War I handed title of Supreme Commander of the 'Volunteer Army' to General-Baron Pyotr Wrangel (b.1878-1928) upon his defeat in the Ukraine in the spring of 1920. Makhnovist forces had helped destroy White influence in Russia though Bolshevik oppression kept them from enjoying the White's demise. By April-May 1920 the White armies were losing ground whilst the Nationalists of Petliura were fleeing to safety in Poland. On 28 April the Bolshevik 14th division assaulted "Makhnograd" (Guliai Pole) and routed 2,000 Makhnovist partisans.

Makhnovist Warfare

Makhnovists would typically raid, burn, loot, destroy and then continue on to their next battle or skirmish. Attacks of German Mennonite estates were particularly brutal, arguably because Makhno himself had suffered cruelty at the hands of these same land owners as a youth. Kulaks, as they were called in Russia and the Ukraine also received harsh treatment at the hands of the Makhnovists and later the Bolsheviks. Tactically they fought strictly on the offensive; preferring to charge, retreat, and charge again, waiting for another moment to strike or counter charge to either break the enemy in their center or retreat in order to make guerrilla attacks again at a later date.

Despite their hard charging fighting style the Revolutionary Insurrection Army was really a defensive minded force, fighting a considerable amount of rearguard actions against much better equipped and organized forces. Against the under-equipped ex-Tsarist armies and the local Mennonite militias however, Makhno triumphed more frequently and held a distinct advantage. He won in style and often in brutality; routed and captured tsarist officers were often summarily executed with bullets from rifles or revolvers or were cut down with the sabres. Makhno was a master of intelligence as well and on several occasions disguised himself as an old women and even a bride at a wedding to gain intelligence.

Fyodor Schuss, center-right, poses with other Makhnovists during the Insurrection

The Soviets took the credit for the Makhnovists victory over the generally despised White officer-warlords in the Ukraine, often demonizing the Makhnovists for any real or imagined crimes and atrocities committed by the Whites against the populace. During their offensive in April & May they took to hanging partisans and setting up individual soviets in the villages they "liberated" from the Whites and Makhnovists.

The fact remained that the Makhnovists had fought for longer against the White Guard's all the while the Red Army was mobilizing and organizing a force from within a revolutionary society still teetering on the brink of collapse. Most of the Makhnovist army fought from horseback each man armed with multiple automatic pistols, a heavily favored weapon of the Makhnovist “officers” and irregular cavalrymen, assorted sabers, daggers and improvised 'peasant' weapons were used as well. Stolen or captured rifles were also very popular amongst the Insurrectionist rebels, including the reliable, accurate, and plentiful M1891 Mosin-Nagant rifle.

Makhnovist officers liked to carry as many weapons as possible as a sign of both rank and prowess in combat. It was a practical solution as well in order to negate reloading in the thick of a charge on horseback. Ammunition and cartridge shortages were a serious problem throughout the Makhnovists campaigns from 1919-1921 so attacks on supply depots and railroad lines were essential for resupply. The Insurrectionists were continually pursued and molested by Red Army cavalry, an arm of the Trotsky's new revolutionary army which would become the most effective fighting force of Soviet Russia.

Schuss (d.1921), a former sailor and one of Makhno's best cavalry commanders

Makhno’s most ingenious tool of war was the tachanka, a very potent and effective mobile weapons platform which the Makhnovists employed heavily. Basically it was a somewhat crude but highly effective horse-drawn heavy weapons system utilizing a “light, sprung cart drawn by two horses (used by Ukrainian peasants), on which Makhno mounted a machine-gun, with two men to work it, plus the driver-The Tachanki gave Makhno a powerful combination of mobility with fire-power, and the device was copied by the Red Army.” –Leon Trotsky .

Bolshevik betrayal: Makhno’s final ride and escape

While allied with the Bolsheviks during three separate periods Makhno and his forces were fundamentally anti-Leninist and anti-Bolshevik etc., conforming to their leader’s own ideas of a “stateless communist society.” A position which Makhno more or less presented to Lenin in a trip to Moscow in 1918. Ultimately the Red Army’s military might and the political will of the new leadership in the Kremlin succeeded in crushing White resistance in mainland Russia from 1919-1920. Any well organized Tsarist resistance ceased when the ‘Black Baron’ Pyotr Wrangel (b.1878-1928) fled to the Crimean peninsula in November of 1920 following a failed summer offensive in the Ukraine. Makhno had some 20,000-40,000 men in arms in the Insurrectionist army in the year 1919.

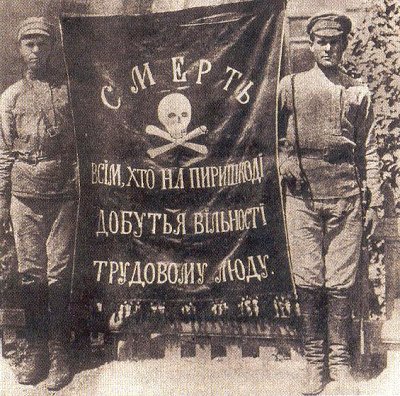

Makhnovist banner

By mid October 1920 however Makhno could field a force possibly as large 10,000-16,000 armed riders and again was allied formally with the Red Army command on the Southern Front trying to prevent Wrangel from escaping the Ukraine to fight again. He had lost hundreds to battle wounds, tuberculosis, and Bolshevik arrests and summary execution. A second front had opened in the Ukraine during this late period with various armies riding through the Ukraine to attack Poland and the Ukraine during the Russian Civil War and the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-1921. Only weeks after the treaty Bolshevik peace treaty, Makhnovists were targeted for summary executions by the the communists.

The end for Makhno; his exile and ideological triumph

Ukraine had been virtually pacified and the Makhnovists all but vanquished saved for Makhno and his remaining die-hards of 6,000-10,000 men. He and his cavalry forces were now engaged in day to day fighting with the Bolsheviks-supposedly fighting 25 battles in 24 days in January of 1921 alone. They managed to best or at least stay one step ahead of the Red Army every time but they were unable to make any real strategic gains. Makhno and his "children" were fighting for their lives in a lost cause. By the middle of winter Makhno and his hundred or so remaining insurgents in arms escape Bolshevik territory into the mountains and plains of Romania or elsewhere. Wounded grievously the Batko left his beloved country for permanent exile in foreign lands.

Ukraine’s chance for independence was all but crushed by the rapidly rising power of the victorious and entirely imperialist Soviet congress of Russia and the might of the Red Army seemingly overnight. Using his connections with academics, writers, and anarchist/socialist activists, Makhno wound up in Paris where he became an active writer and debater of the Anarchist cause. Composing recollections of a great deal of his own experiences and composing other essays on anarchism and other various revolutionary ideologies, he became a politico and historian in later life. Troubled by old war wounds and a never healed bout from tuberculosis from his years spent in tsarist prisons, Nestor Makhno died in Paris on 6 July 1934.

Though his revolution had ultimately failed, Batko Makhno would forever tout the black flag of anarchism, supporting anarchism for the people of Ukraine and in Russia until his death with his writings and speeches. One of his frequent subjects was the corruption of Bolshevik-communism in theSoviet Union and elsewhere which he felt had re-enslaved the proletariat yet again, as was true in his country of birth and in neighboring countries as well.He also wrote on the socio-political situation in Spain at the time as well, predicting a left wing-right wing socialist inspired conflict upcoming in the Spanish Civil War.

Insurgent guerrilla, general, and writer, 'Batko' Nestor Makhno

Makhno continued writing on the history of the Makhnovist movement and its greater ideals throughout his exile, defending it from criticism often in his writings and speeches. When he met the famed Spanish Anarchist and revolutionary martyr José Buenaventura Durruti (b.1896-1936) in 1927, Makhno exclaimed to the young anarchist and his companions before they left the gathering, "Makhno has never shirked a fight! If I am still alive when you begin [Spanish revolution/civil war] I will be with you."

The State will, though, be able to cling to a few local enclaves and try to place multifarious obstacles in the path of the toilers’ new life, slowing the pace of growth and harmonious development of new relationships founded on the complete emancipation of man.

The final and utter liquidation of the State can only come to pass when the struggle of the

toilers is oriented along the most libertarian lines possible, when the toilers will

themselves determine the structures of their social action. These structures should

assume the form of organs of social and economic self-direction, the form of free “anti-

authoritarian” soviets. The revolutionary workers and their vanguard — the anarchists —

must analyze the nature and structure of these soviets and specify their revolutionary

functions in advance. It is upon that, chiefly, that the positive evolution and development

of anarchist ideas, in the ranks of those who will accomplish the liquidation of the State on their own account in order to build a free society, will be dependent.

Dyelo Truda No.17, October 1926

Makhnovist Flag (trans.)