1/27/2020

A University of California, Berkeley, archaeologist has dug up ancient human feces, among other demographic clues, to challenge the narrative around the legendary demise of Cahokia, North America's most iconic pre-Columbian metropolis.

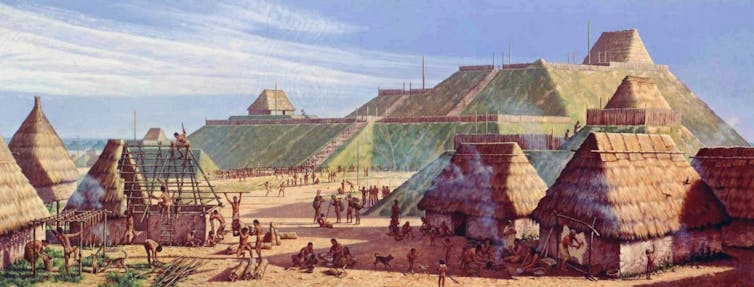

Painting of the Cahokia Mounds by William R. Iseminger [Credit: Cahokia Mounds Historic State Site]

In its heyday in the 1100s, Cahokia -- located in what is now southern Illinois -- was the center for Mississippian culture and home to tens of thousands of Native Americans who farmed, fished, traded and built giant ritual mounds.

By the 1400s, Cahokia had been abandoned due to floods, droughts, resource scarcity and other drivers of depopulation. But contrary to romanticized notions of Cahokia's lost civilization, the exodus was short-lived, according to a new UC Berkeley study.

The study takes on the "myth of the vanishing Indian" that favors decline and disappearance over Native American resilience and persistence, said lead author A.J. White, a UC Berkeley doctoral student in anthropology.

"One would think the Cahokia region was a ghost town at the time of European contact, based on the archaeological record," White said. "But we were able to piece together a Native American presence in the area that endured for centuries."

The findings, just published in the journal American Antiquity, make the case that a fresh wave of Native Americans repopulated the region in the 1500s and kept a steady presence there through the 1700s, when migrations, warfare, disease and environmental change led to a reduction in the local population.

White and fellow researchers at California State University, Long Beach, the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Northeastern University analyzed fossil pollen, the remnants of ancient feces, charcoal and other clues to reconstruct a post-Mississippian lifestyle.

Their evidence paints a picture of communities built around maize farming, bison hunting and possibly even controlled burning in the grasslands, which is consistent with the practices of a network of tribes known as the Illinois Confederation.

Unlike the Mississippians who were firmly rooted in the Cahokia metropolis, the Illinois Confederation tribe members roamed further afield, tending small farms and gardens, hunting game and breaking off into smaller groups when resources became scarce.

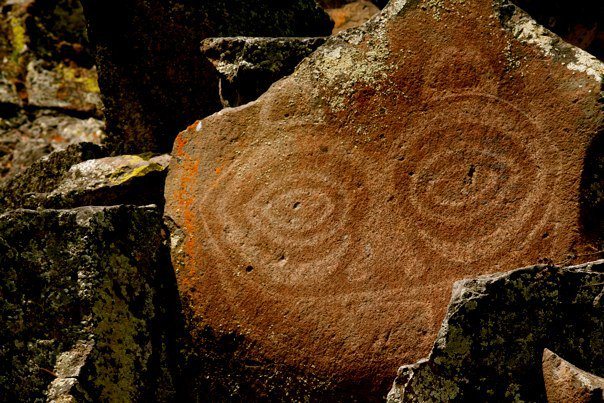

Credit: Herb Roe, University of California - Berkeley

The linchpin holding together the evidence of their presence in the region were "fecal stanols" derived from human waste preserved deep in the sediment under Horseshoe Lake, Cahokia's main catchment area.

Fecal stanols are microscopic organic molecules produced in our gut when we digest food, especially meat. They are excreted in our feces and can be preserved in layers of sediment for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

Because humans produce fecal stanols in far greater quantities than animals, their levels can be used to gauge major changes in a region's population.

To collect the evidence, White and colleagues paddled out into Horseshoe Lake, which is adjacent to Cahokia Mounds State Historical Site, and dug up core samples of mud some 10 feet below the lakebed. By measuring concentrations of fecal stanols, they were able to gauge population changes from the Mississippian period through European contact.

Fecal stanol data were also gauged in White's first study of Cahokia's Mississippian Period demographic changes, published last year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It found that climate change in the form of back-to-back floods and droughts played a key role in the exodus of Cahokia's Mississippian inhabitants.

But while many studies have focused on the reasons for Cahokia's decline, few have looked at the region following the exodus of Mississippians, whose culture is estimated to have spread through the Midwestern, Southeastern and Eastern United States from 700 A.D. to the 1500s.

White's latest study sought to fill those gaps in the Cahokia area's history.

"There's very little archaeological evidence for an indigenous population past Cahokia, but we were able to fill in the gaps through historical, climatic and ecological data, and the linchpin was the fecal stanol evidence," White said.

Overall, the results suggest that the Mississippian decline did not mark the end of a Native American presence in the Cahokia region, but rather reveal a complex series of migrations, warfare and ecological changes in the 1500s and 1600s, before Europeans arrived on the scene, White said.

"The story of Cahokia was a lot more complex than, 'Goodbye, Native Americans. Hello, Europeans,' and our study uses innovative and unusual evidence to show that," White said.

Author: Yasmin Anwar | Source: University of California - Berkeley [January 27, 2020]