Sailko/The Mauritshuis/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Detail from Rembrandt van Rijn’s painting Two African Men.

February 01, 2025

The so-called golden age of Dutch painting in the 1600s coincided with an economic boom that had a lot to do with the transatlantic slave trade. But how did the slave trade shape the art market in the Netherlands? And how is it reflected in the paintings of the time?

This is the subject of a new book called Slavery and the Invention of Dutch Art by art historian Caroline Fowler. We asked about her study.

The so-called golden age of Dutch painting in the 1600s coincided with an economic boom that had a lot to do with the transatlantic slave trade. But how did the slave trade shape the art market in the Netherlands? And how is it reflected in the paintings of the time?

This is the subject of a new book called Slavery and the Invention of Dutch Art by art historian Caroline Fowler. We asked about her study.

What was Dutch art about before slavery and what was the golden age?

The earliest paintings that would be called Dutch were predominantly religious. They were made for Christian devotion. In the 1500s, major divisions in the church led to a fragmentation of Christianity called the Reformation.

In this new religious climate, artists began to create new types of paintings, studying the world around them. They included landscapes, seascapes, still lifes, and interior scenes of their homes. Instead of working for the church, many painters began to work within an art market. There was a rising middle class that could afford to buy paintings.

Historically, this period in Dutch economic prosperity has been called the “golden age”. This is when many of the most famous Dutch painters worked, such as Rembrandt van Rijn and Johannes Vermeer.

Their work was made possible by a strong Dutch economy built on global trade networks. This included the transatlantic slave trade and the rise of the middle class. Although artists did not directly paint the transatlantic slave trade, in my book I argue that it is central to understanding the paintings produced in the 1600s as it made the economic market possible.

In turn, many of the types of painting that developed, like maritime scenes and interior scenes, are often obliquely or directly about international trade. The slave trade is a haunting presence in these images.

How did this play out within Dutch colonialism?

The new “middle class” consisted of economically prosperous merchants, artisans, lawyers and doctors. For many of the wealthiest merchants, their prosperity was fuelled by their investments in trade overseas. In land and plantations, and also commodities such as sugar, salt, mace and nutmeg.

Slavery was illegal within the boundaries of the Dutch Republic on the European continent. But it was widely practised within Dutch colonies around the world. Slavery was central to their trade overseas – from the inter-Asian slave network that made possible their domination in the export of nutmeg, to the use of enslaved labour on plantations in the Americas. It also contributed in less visible ways to Dutch economic prosperity, like the development of maritime insurance.

What was the relationship between artists and Dutch colonies?

In the new school of painting, artists would sometimes travel to the Dutch colonies. For example, Frans Post travelled to Dutch Brazil and painted the sugar plantations and mills. Another artist named Maria Sibylla Merian went to Dutch Suriname, where she studied butterflies and plants on the Dutch sugar plantations.

Both depict landscapes and the natural world but don’t directly engage with the profound dehumanisation of slavery, and an economic system dependent on enslaved labour. But this doesn’t mean that it’s absent in their sanitised renditions.

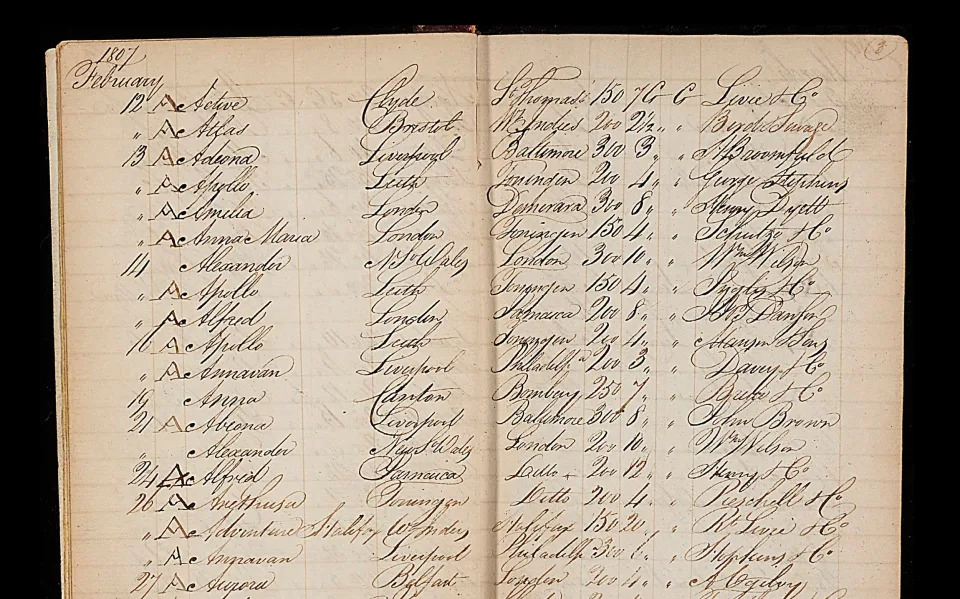

Among the sources that I used to think about the presence of the transatlantic slave trade in a culture that did not overtly depict it were inventories of paintings and early museum collections. Often the language in these sources differed from the painting in important ways. They demonstrate how the violence of the system emerges in unexpected places.

One inventory that describes paintings by Frans Post, for example, also narrates the physical punishment meted out if the enslaved tried to run away from the Dutch sugar plantations. This isn’t depicted in the painting, but it is part of the inventory that travelled beside the painting.

These moments reveal the profound presence of this system within Dutch painting, and point to the ways in which artists negotiated making this structure invisible in their paintings although they were not able to completely erase its presence.

How do you discuss Rembrandt’s paintings in your book?

Historically, studies of the transatlantic slave trade in early modern painting (about 1400-1700) have looked at paintings that directly depict either enslaved or Black individuals.

One of the points of this book is that this limits our understanding of the transatlantic slave trade in Dutch painting. A focus on blackness, for example, precludes understanding how whiteness is constructed at the same time. It fails to recognise the ways in which artists sought to diminish the presence of the slave trade in their sanitised rendition of Dutch society.

One painting that I use to think about this is Rembrandt van Rijn’s very famous work called Syndics of the Draper’s Guild. It’s a group portrait of wealthy, white merchants gathered around a table looking at a book of fabric samples.

Although there aren’t enslaved or black individuals depicted, this painting would be impossible without the transatlantic slave trade. Cloth from the Netherlands was often exchanged for enslaved people in west Africa, for example.

In my book, I draw attention to these understudied histories to understand how certain assumptions around whiteness, privilege, and wealth developed in tandem with an emerging visual vocabulary around blackness and the transformation of individual lives into chattel property.

What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

I hope that readers will think about how many of our ideas about freedom, the middle class, art markets, and economic prosperity began in the 17th-century Dutch Republic. As this book demonstrates, a central part of this narrative that has been overlooked was the transatlantic slave trade in building this fantasy.

This is in many ways an invention that traces back to the paintings of overt consumption and wealth produced in the Dutch Republic – like Vermeer’s interiors of Dutch homes.

My aim with this book is to present not only a more complex view of Dutch painting but also a reconsideration of certain dogmas today around prosperity and the art market. The rise of our current financial system, art markets and visible celebration of landscapes, seascapes and interior scenes are all inseparable from the transformation of individual lives into property. We live with this legacy today in our systems built on racial, economic and gendered inequalities.

Caroline Fowler, Starr Director of the Research and Academic Program, Clark Art Institute, and lecturer in Art History, Williams College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

I hope that readers will think about how many of our ideas about freedom, the middle class, art markets, and economic prosperity began in the 17th-century Dutch Republic. As this book demonstrates, a central part of this narrative that has been overlooked was the transatlantic slave trade in building this fantasy.

This is in many ways an invention that traces back to the paintings of overt consumption and wealth produced in the Dutch Republic – like Vermeer’s interiors of Dutch homes.

My aim with this book is to present not only a more complex view of Dutch painting but also a reconsideration of certain dogmas today around prosperity and the art market. The rise of our current financial system, art markets and visible celebration of landscapes, seascapes and interior scenes are all inseparable from the transformation of individual lives into property. We live with this legacy today in our systems built on racial, economic and gendered inequalities.

Caroline Fowler, Starr Director of the Research and Academic Program, Clark Art Institute, and lecturer in Art History, Williams College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dutch Golden Age: Johan de Witt speech from the film Michiel de Ruyter, Dutch with English subtitles

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/JUDMD6FVWZEP5N3B3OXPT46VII.jpg)