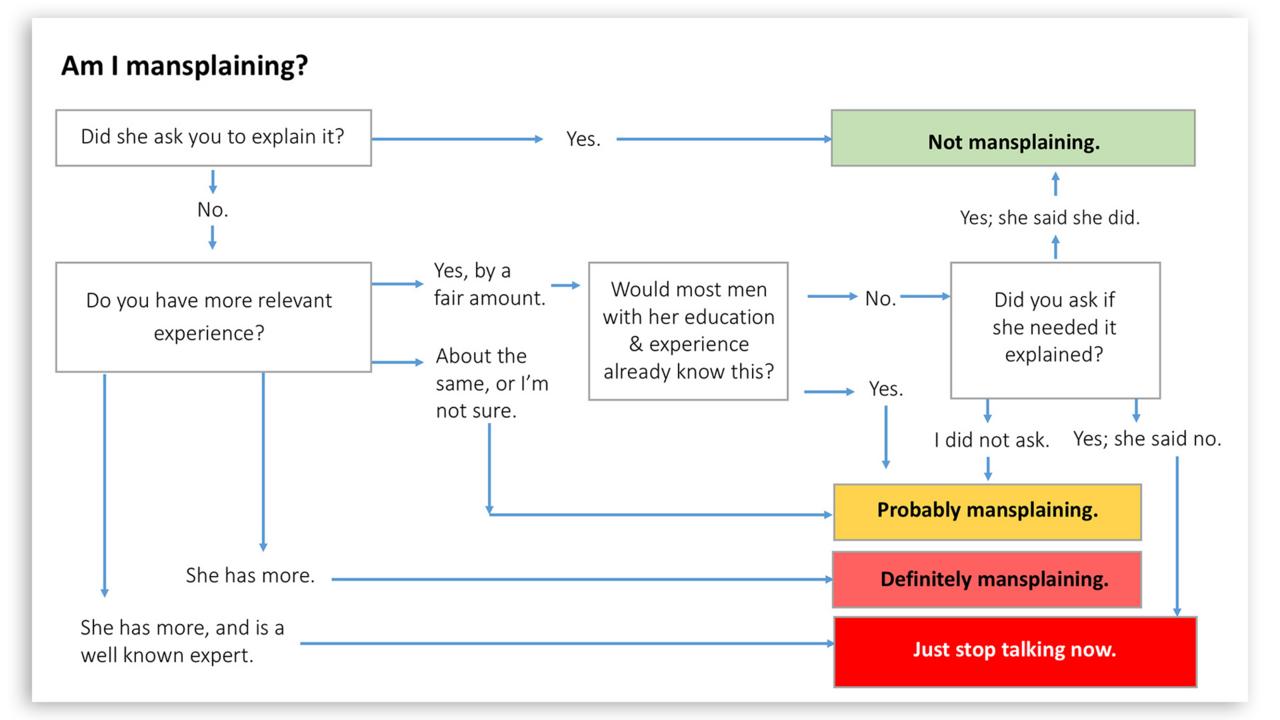

Mansplaining, explained in one simple chart

CLICK ON CHART TO MAKE IT BIGGER

Mansplaining is, at its core, a very specific thing. It's what occurs when a man talks condescendingly to someone (especially a woman) about something he has incomplete knowledge of, with the mistaken assumption that he knows more about it than the person he's talking to does.

Although mansplain is most likely the coinage of a LiveJournal user (thanks, Know Your Meme), no discussion of mansplain is complete without mention of Rebecca Solnit's 2008 essay "Men Explain Things to Me," now also the title of her 2014 collection of essays. (The essay was published first at TomDispatch.com and later in the Los Angeles Times. It was reprinted in Guernica with a new introduction by Solnit in 2012.) Although Solnit didn't use the word mansplain in her essay, she described what might be the most mansplainiest of experiences anyone has ever had. Solnit and a friend were at a party where the host (a wealthy and imposing older man), upon learning that Solnit had recently published a book on 19th century photographer Eadweard Muybridge, proceeded to tell her all about a very important book on the same photographer that had just come out. The book, of course, was Solnit's, but the man had to be interrupted several times by Solnit's friend before he'd absorbed that knowledge and added it to the knowledge he'd absorbed from reading the New York Times review of the book.

Mansplaining gained traction at first on feminist blogs, as writers and activists finally had a catchall way to talk about a specific, albeit insidious, dynamic experienced by qualified women in male-dominated fields. When I heard it for the first time, the term helped to instantly describe so many interactions I had with men over the years that left me feeling annoyed and bad about myself. Mansplaining encapsulates the sexist, condescending tendency men can exhibit in classrooms, at work, and in casual conversation to assume that they know more about a topic than a woman, no matter what it is or what her credentials are.

But as it’s become a household phrase on the internet in the last few years, mansplaining has been used to characterize an ever-growing variety of unpleasant or uncomfortable interactions between a man and a woman, even those that aren’t actually marked by sexist aggression. Maloney’s apology to Hill for the mansplaining she “endured,” for example, belies the fact that members of Congress have castigated both male and female witnesses at the impeachment hearings (as they often do at most hearings, really). Solnit herself has said that mansplaining is applied too broadly; part of this is because of how viral moments in politics and otherwise travel now, quickly and without context — something pithy and broad like mansplaining acts like a stamp, telling us how to react and share.

Which is the much more worrisome implication of mansplaining’s ballooning definition: that some people, many of whom actually oppose the goals of feminism, have figured out how to use it as a political attack, to deflect engagement with the contents of their positions.

No comments:

Post a Comment