A REVOLUTION OF YOUTH AND WOMEN

‘Our friends didn’t die in vain’: Sudan’s activists aim to topple military regime

In the struggle for democracy in Sudan, protesters in Khartoum demonstrate against military rule in March this year. Photograph: Marwan Ali/AP

Three years after protests toppled Omar al-Bashir, activists hope to bring down another government with little more than phones, placards and motorbikes

Jason Burke & Zeinab Mohammed Salih

Three years after protests toppled Omar al-Bashir, activists hope to bring down another government with little more than phones, placards and motorbikes

Jason Burke & Zeinab Mohammed Salih

in Khartoum

Sat 28 May 2022

A small house on a street in central Khartoum, lost among the dusty blocks of offices and cheap hotels but not difficult to find. On the wall outside, a slightly faded portrait of the smiling young man who once lived here: Abdulsalam Kisha.

Inside, half a dozen men and a woman are meeting, planning, eating, joking. These self-styled “revolutionaries” do not belong to a political party, or even a defined organisation. Instead, they are part of a coalition of hundreds of grassroots associations across Sudan’s towns and cities coordinated by activists who hope to bring down a powerful military regime with little more than placards, smartphones and motorbikes. The efforts of these “resistance committees” in Sudan are being watched – with hope by many, anxiety by autocratic leaders – across a swathe of the Middle East and Africa.

Their efforts are not without risk, however. Nearly 1,600 pro-democracy campaigners in Sudan have been arrested in the past eight months, and 96 killed in a series of protests. Almost every weekend, the police deploy shotguns and teargas to clear streets of barricades and demonstrators. More than 100 were injured in three days last week alone.

Among those meeting in Kisha’s house are a 58-year-old housewife and her 63-year-old retired agricultural engineer husband whose involvement in such dangerous and committed activism would seem astonishing unless you knew of their history. Kisha, a charismatic and popular 25-year-old law student, was killed by a bullet during the uprising that ended the 30-year rule of Sudan’s autocratic Islamist leader, Omar al-Bashir, in 2019, and appeared to usher in a new era of democracy. The house is where Kisha grew up, clambering across the cluttered courtyard, playing in the dusty street outside, leaving to attend school then university and finally to walk 100m to the protest where he died. The middle-aged couple are his parents.

This week, on the third anniversary of their son’s death, they will take to the streets yet again, shouting themselves hoarse, evading police checkposts, chanting the protest songs with the others, most 30 or even 40 years younger.

“What else can we do?” they said. “We are the parents of a martyr. We have to be there to inspire the others.”

Others in the room, a generation younger, explain their participation similarly. “We have to go on and risk our lives, so that our friends did not die in vain,” said one.

For most of those involved with the resistance committees, the campaign is their third battle for democracy in Sudan, a strategically located country of 44 million people which has suffered a series of autocratic regimes and wars since declaring independence from Britain in 1955.

The first such effort was waged over almost a decade to overthrow Bashir. Then, for a few short weeks from April 2019, came a second: to force democracy on the soldiers and paramilitaries who took power after the dictator’s fall. This ended bloodily. At least 200 were killed and more injured when an unprecedented sit-in was brutally broken up.

“It was a very beautiful moment when Bashir fell. We dreamed of a Sudan where everyone was free to be and say what they wanted … But looking back now, we were very naive,” said “Carbino”, a leader of a resistance committee in south Khartoum.

A small house on a street in central Khartoum, lost among the dusty blocks of offices and cheap hotels but not difficult to find. On the wall outside, a slightly faded portrait of the smiling young man who once lived here: Abdulsalam Kisha.

Inside, half a dozen men and a woman are meeting, planning, eating, joking. These self-styled “revolutionaries” do not belong to a political party, or even a defined organisation. Instead, they are part of a coalition of hundreds of grassroots associations across Sudan’s towns and cities coordinated by activists who hope to bring down a powerful military regime with little more than placards, smartphones and motorbikes. The efforts of these “resistance committees” in Sudan are being watched – with hope by many, anxiety by autocratic leaders – across a swathe of the Middle East and Africa.

Their efforts are not without risk, however. Nearly 1,600 pro-democracy campaigners in Sudan have been arrested in the past eight months, and 96 killed in a series of protests. Almost every weekend, the police deploy shotguns and teargas to clear streets of barricades and demonstrators. More than 100 were injured in three days last week alone.

Among those meeting in Kisha’s house are a 58-year-old housewife and her 63-year-old retired agricultural engineer husband whose involvement in such dangerous and committed activism would seem astonishing unless you knew of their history. Kisha, a charismatic and popular 25-year-old law student, was killed by a bullet during the uprising that ended the 30-year rule of Sudan’s autocratic Islamist leader, Omar al-Bashir, in 2019, and appeared to usher in a new era of democracy. The house is where Kisha grew up, clambering across the cluttered courtyard, playing in the dusty street outside, leaving to attend school then university and finally to walk 100m to the protest where he died. The middle-aged couple are his parents.

This week, on the third anniversary of their son’s death, they will take to the streets yet again, shouting themselves hoarse, evading police checkposts, chanting the protest songs with the others, most 30 or even 40 years younger.

“What else can we do?” they said. “We are the parents of a martyr. We have to be there to inspire the others.”

Others in the room, a generation younger, explain their participation similarly. “We have to go on and risk our lives, so that our friends did not die in vain,” said one.

For most of those involved with the resistance committees, the campaign is their third battle for democracy in Sudan, a strategically located country of 44 million people which has suffered a series of autocratic regimes and wars since declaring independence from Britain in 1955.

The first such effort was waged over almost a decade to overthrow Bashir. Then, for a few short weeks from April 2019, came a second: to force democracy on the soldiers and paramilitaries who took power after the dictator’s fall. This ended bloodily. At least 200 were killed and more injured when an unprecedented sit-in was brutally broken up.

“It was a very beautiful moment when Bashir fell. We dreamed of a Sudan where everyone was free to be and say what they wanted … But looking back now, we were very naive,” said “Carbino”, a leader of a resistance committee in south Khartoum.

Omar al-Bashir, the Sudanese president who was ousted in 2019.

Photograph: Ashraf Shazly/AFP/Getty Images

Despite the brutality, the protests of 2019 did win a partial victory, with Sudan’s powerful army and allied paramilitaries forced to concede the creation of a mixed civilian-military administration that was supposed to prepare the way for elections. Once again, however, hopes of a better future were dashed. A military coup in October ended any dream of democracy, and so the resistance committees formed to fight for a third time for radical change.

“This time we have our eyes wide open, and will not accept anything other than all our demands: peace, justice and freedom,” Carbino said.

This new effort is a scrappy affair, unlike the big demonstrations that brought down Bashir or the protracted mass sit-in that followed. It is a campaign of pop-up protests, running battles with the police, graffiti on walls at night, clandestine leaflet deliveries, demonstrations organised only hours before and instructions circulated on social media.

On a Saturday night, it is the turn of the resistance committee in Burri, a middle-class neighbourhood near Khartoum’s international airport. As the barricades of bricks and rocks go up, the shutters on the shops come down. A grocer stays open a few minutes longer to allow housewives to run last-minute errands for sugar, cooking oil or bread. Then the young men fill the streets and wait for the police.

“We have to do this, for freedom,” said Omar, 27 years old and jobless, as he watched the first attempts of the police to disperse the protesters. Heavy armoured trucks manoeuvre, pushing forward with squads of policemen alongside.

That a sharp wind blows the clouds of teargas back towards the advancing vehicles does not please Omar.

“That’s bad … It means they will use live ammunition instead,” he warned, and soon after there is a volley of shots. The teenage protesters fall back, then gather their resolve and return to the street. Flames from burning tyres flicker in the dusk. And so it goes on, through the evening.

In moments of relative calm, women gather errant children and complain about the disruption. Many worry too. “We want this to stop … Our young people are dying,” said one, as she sheltered in a neighbour’s yard.

The rhythm of the protests is irregular, but preparations are well-rehearsed. A baking powder solution helps deal with teargas and so, the demonstrators say, do anti-Covid masks. Then there are goggles and builder’s hard hats that are supposed to protect against shotgun pellets. Those with motorbikes stand ready to pick up the injured, taking them to local clinics where they are treated by sympathetic doctors.

Despite the brutality, the protests of 2019 did win a partial victory, with Sudan’s powerful army and allied paramilitaries forced to concede the creation of a mixed civilian-military administration that was supposed to prepare the way for elections. Once again, however, hopes of a better future were dashed. A military coup in October ended any dream of democracy, and so the resistance committees formed to fight for a third time for radical change.

“This time we have our eyes wide open, and will not accept anything other than all our demands: peace, justice and freedom,” Carbino said.

This new effort is a scrappy affair, unlike the big demonstrations that brought down Bashir or the protracted mass sit-in that followed. It is a campaign of pop-up protests, running battles with the police, graffiti on walls at night, clandestine leaflet deliveries, demonstrations organised only hours before and instructions circulated on social media.

On a Saturday night, it is the turn of the resistance committee in Burri, a middle-class neighbourhood near Khartoum’s international airport. As the barricades of bricks and rocks go up, the shutters on the shops come down. A grocer stays open a few minutes longer to allow housewives to run last-minute errands for sugar, cooking oil or bread. Then the young men fill the streets and wait for the police.

“We have to do this, for freedom,” said Omar, 27 years old and jobless, as he watched the first attempts of the police to disperse the protesters. Heavy armoured trucks manoeuvre, pushing forward with squads of policemen alongside.

That a sharp wind blows the clouds of teargas back towards the advancing vehicles does not please Omar.

“That’s bad … It means they will use live ammunition instead,” he warned, and soon after there is a volley of shots. The teenage protesters fall back, then gather their resolve and return to the street. Flames from burning tyres flicker in the dusk. And so it goes on, through the evening.

In moments of relative calm, women gather errant children and complain about the disruption. Many worry too. “We want this to stop … Our young people are dying,” said one, as she sheltered in a neighbour’s yard.

The rhythm of the protests is irregular, but preparations are well-rehearsed. A baking powder solution helps deal with teargas and so, the demonstrators say, do anti-Covid masks. Then there are goggles and builder’s hard hats that are supposed to protect against shotgun pellets. Those with motorbikes stand ready to pick up the injured, taking them to local clinics where they are treated by sympathetic doctors.

Ijlal Syed Bashera, wearing goggles to counter the teargas, at a protest in Omdurman. Photograph: Jason Burke/The Observer

A day after the protests in Burri, it is the turn of Omdurman, Khartoum’s twin city just across the river Nile. Kisha’s parents are planning to join protests there, though may be stopped either by police checkpoints or arthritis.

By 3pm, despite temperatures above 40C, crowds have gathered on Shaheed Abdulazeem street. The makeshift rock barricades are already up amid drumming and chanting. There are teenagers from the neighbourhood, lots of students, and a core of very determined older protesters.

Momin Ahmed, 27, was shot in January at a demonstration and lost most of the use of his arm. “We are thousands…[so] I am not afraid,” he said. Ijlal Syed Bashera, 43, has brought her two children, aged nine and 12, to “learn the true meaning of patriotism”. Unemployed despite degrees in politics and computing, she has been protesting since 2013 in each of the three efforts for democracy and has been arrested three times too.

“It is simple. We want a better life. There is total economic collapse. There is no freedom. So obviously we protest,” she said.

Some doubt the depth and breadth of the protesters support, painting them as relatively well-off urbanites out of touch with Sudan’s often deeply conservative population. There is little doubt that the current unrest is restricted to bigger towns and cities, and that, even in Khartoum, it is not mobilising masses or causing significant disruption. On Africa Street, a broad thoroughfare not far from the Omdurman protests, patrons enjoy fried fish, stewed beans and kebabs in packed restaurants despite the acrid smell of teargas on the evening breeze.

Pro-democracy activists claim such apparent apathy is deceptive, and that they have genuine grassroots support. Osman Basri, a lawyer who represents detained campaigners, said a combination of holidays, the deliberately decentralised strategy and repression had depressed numbers.

“What you see is the tip of the iceberg. There are the visible protesters, but a huge mass of people who support us but don’t show it,” he said,

There are good reasons to remain unnoticed by security forces. Emergency laws currently in place allow arbitrary arrest and detention. Abuses are systematic.

“I was held for six weeks and was never charged, saw no lawyer, could not call my family. When I went on hunger strike to complain I was put in a small cell called the fridge, where an air conditioner was kept on maximum and lights on all day and night,” said “Rasta”, a member of a central Khartoum resistance committee.

Others report chronic overcrowding, brutal beatings, sleep deprivation, repeated humiliation and denial of medical treatment. Age or infirmity makes little difference. If detained, the parents of Kisha would receive the same treatment as anyone else, Basri said.

A day after the protests in Burri, it is the turn of Omdurman, Khartoum’s twin city just across the river Nile. Kisha’s parents are planning to join protests there, though may be stopped either by police checkpoints or arthritis.

By 3pm, despite temperatures above 40C, crowds have gathered on Shaheed Abdulazeem street. The makeshift rock barricades are already up amid drumming and chanting. There are teenagers from the neighbourhood, lots of students, and a core of very determined older protesters.

Momin Ahmed, 27, was shot in January at a demonstration and lost most of the use of his arm. “We are thousands…[so] I am not afraid,” he said. Ijlal Syed Bashera, 43, has brought her two children, aged nine and 12, to “learn the true meaning of patriotism”. Unemployed despite degrees in politics and computing, she has been protesting since 2013 in each of the three efforts for democracy and has been arrested three times too.

“It is simple. We want a better life. There is total economic collapse. There is no freedom. So obviously we protest,” she said.

Some doubt the depth and breadth of the protesters support, painting them as relatively well-off urbanites out of touch with Sudan’s often deeply conservative population. There is little doubt that the current unrest is restricted to bigger towns and cities, and that, even in Khartoum, it is not mobilising masses or causing significant disruption. On Africa Street, a broad thoroughfare not far from the Omdurman protests, patrons enjoy fried fish, stewed beans and kebabs in packed restaurants despite the acrid smell of teargas on the evening breeze.

Pro-democracy activists claim such apparent apathy is deceptive, and that they have genuine grassroots support. Osman Basri, a lawyer who represents detained campaigners, said a combination of holidays, the deliberately decentralised strategy and repression had depressed numbers.

“What you see is the tip of the iceberg. There are the visible protesters, but a huge mass of people who support us but don’t show it,” he said,

There are good reasons to remain unnoticed by security forces. Emergency laws currently in place allow arbitrary arrest and detention. Abuses are systematic.

“I was held for six weeks and was never charged, saw no lawyer, could not call my family. When I went on hunger strike to complain I was put in a small cell called the fridge, where an air conditioner was kept on maximum and lights on all day and night,” said “Rasta”, a member of a central Khartoum resistance committee.

Others report chronic overcrowding, brutal beatings, sleep deprivation, repeated humiliation and denial of medical treatment. Age or infirmity makes little difference. If detained, the parents of Kisha would receive the same treatment as anyone else, Basri said.

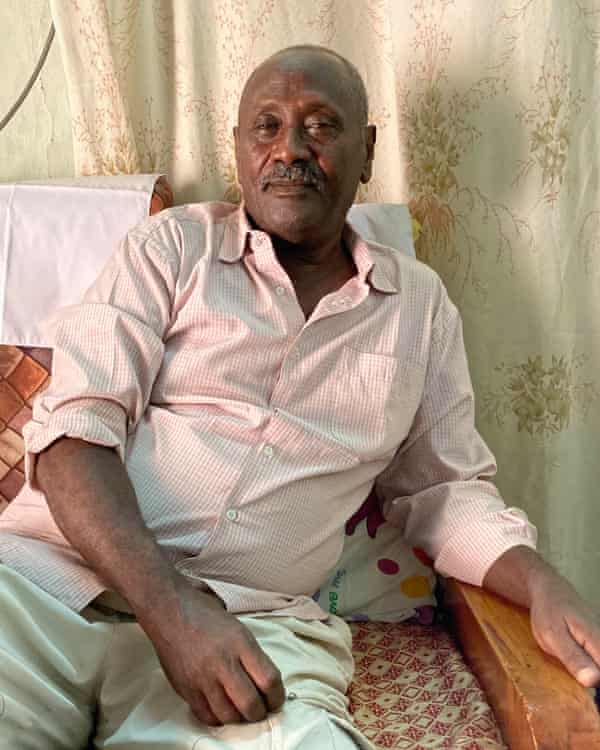

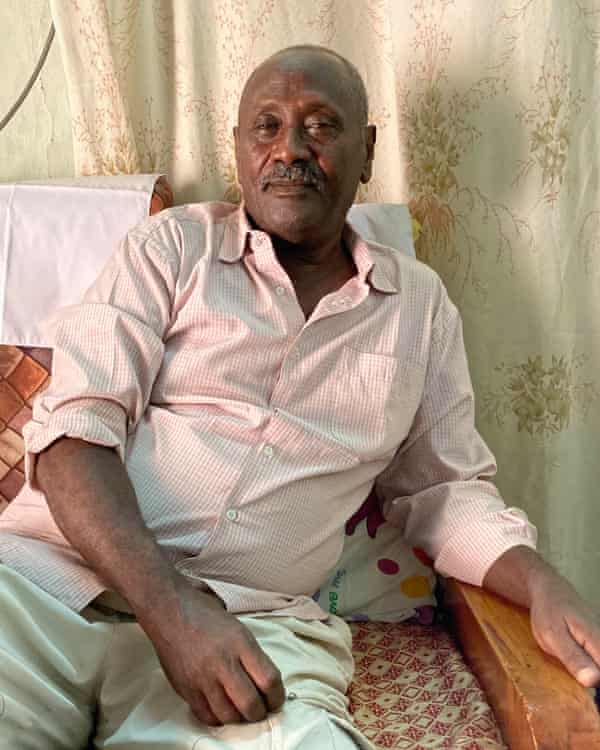

Abdulsalam Kisha’s father, a retired engineer.

Photograph: Jason Burke/The Observer

By late afternoon in Omdurman, the police have been reinforced and canisters of tear gas fired in broadsides from trucks clatter off the potholed road. Young men run, choking, crying but waving V for victory signs. They ignore stacks of pebbles at a construction site. The resistance committees insist their protests are non-violent, and so far discipline has held.

Everyone knows the stakes are high, and not just for Sudan. More than a decade after the pro-democracy uprisings of the Arab spring, millions across the Middle East are watching what happens in Khartoum, Omdurman and across the country. So, too, are others across Africa, where democracy has been retreating in the face of renewed repression from Zimbabwe to Mali. The future of Sudan is especially important for the chain of unstable states running from Senegal to Somalia.

“This is a contest of totally different and incompatible visions of politics,” said Kholood Khair, founding director of Confluence Advisory, a thinktank in Khartoum.

On one side are the political elites, the rebel groups, the military and paramilitaries with their patronage-based politics, back-room deals and distribution of the country’s resources between those strong enough to claim a share. On the other is the street, and a vision of transformational change based on entirely new ideas about civilian government.

“The military have a lot of patrimonial power and military might. The street has the numbers, new ideas and time … At the moment, we are at an impasse,” said Khair. “For pro-democracy movements, Sudan is a kind of proof of concept that change can come. If they can do it in Sudan, they can do it elsewhere. And there are lots of people excited by that, but lots very worried by it, too.”

Many analysts in Khartoum say that a decisive moment is fast approaching. The country is already plunged in economic crisis, partly a consequence of last October’s coup which led the US, World Bank and other major donors to cut off the flow of billions of dollars of aid.

Millions are already hungry, violence is rising in restive regions such as Darfur and inflation is running at 250%. If people start to go hungry or can no longer afford fuel or find work, the relatively modest protests could rapidly swell into the massive demonstrations that brought down Bashir’s government in 2019.

The most powerful military rulers of Sudan – Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as “Hemedti” – now find themselves in a quandary. To stave off economic collapse and widespread protests, they need international aid. But to get it they need to make concessions and at least bring some of Sudan’s mainstream civilian politicians back into government. The resistance committees would see this as another betrayal, however, and would protest, inevitably prompting the sort of repression that would undermine any compromise. Meanwhile, the economy would deteriorate further.

The Abdulsalam family are not bothered by any of this. They say they will remain true to the ideas and ambitions that attracted their son to the protest movement against Bashir and led to his death three years ago.

“The French Revolution took many years to be successful,” said Kisha’s father, as the rest of the resistance committee ate a rapid lunch before heading out to another protest. “We have only just started ours.”

By late afternoon in Omdurman, the police have been reinforced and canisters of tear gas fired in broadsides from trucks clatter off the potholed road. Young men run, choking, crying but waving V for victory signs. They ignore stacks of pebbles at a construction site. The resistance committees insist their protests are non-violent, and so far discipline has held.

Everyone knows the stakes are high, and not just for Sudan. More than a decade after the pro-democracy uprisings of the Arab spring, millions across the Middle East are watching what happens in Khartoum, Omdurman and across the country. So, too, are others across Africa, where democracy has been retreating in the face of renewed repression from Zimbabwe to Mali. The future of Sudan is especially important for the chain of unstable states running from Senegal to Somalia.

“This is a contest of totally different and incompatible visions of politics,” said Kholood Khair, founding director of Confluence Advisory, a thinktank in Khartoum.

On one side are the political elites, the rebel groups, the military and paramilitaries with their patronage-based politics, back-room deals and distribution of the country’s resources between those strong enough to claim a share. On the other is the street, and a vision of transformational change based on entirely new ideas about civilian government.

“The military have a lot of patrimonial power and military might. The street has the numbers, new ideas and time … At the moment, we are at an impasse,” said Khair. “For pro-democracy movements, Sudan is a kind of proof of concept that change can come. If they can do it in Sudan, they can do it elsewhere. And there are lots of people excited by that, but lots very worried by it, too.”

Many analysts in Khartoum say that a decisive moment is fast approaching. The country is already plunged in economic crisis, partly a consequence of last October’s coup which led the US, World Bank and other major donors to cut off the flow of billions of dollars of aid.

Millions are already hungry, violence is rising in restive regions such as Darfur and inflation is running at 250%. If people start to go hungry or can no longer afford fuel or find work, the relatively modest protests could rapidly swell into the massive demonstrations that brought down Bashir’s government in 2019.

The most powerful military rulers of Sudan – Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as “Hemedti” – now find themselves in a quandary. To stave off economic collapse and widespread protests, they need international aid. But to get it they need to make concessions and at least bring some of Sudan’s mainstream civilian politicians back into government. The resistance committees would see this as another betrayal, however, and would protest, inevitably prompting the sort of repression that would undermine any compromise. Meanwhile, the economy would deteriorate further.

The Abdulsalam family are not bothered by any of this. They say they will remain true to the ideas and ambitions that attracted their son to the protest movement against Bashir and led to his death three years ago.

“The French Revolution took many years to be successful,” said Kisha’s father, as the rest of the resistance committee ate a rapid lunch before heading out to another protest. “We have only just started ours.”

Abdulsalam Kisha’s mother, also an activist, at home with a picture of her son who was killed in a protest three years ago.

Photograph: Jason Burke/The Observer

No comments:

Post a Comment