A startup founded by SpaceX veterans aims to realize the potential of a technology whose big promises have never quite come through.

Freeform Future co-founder and Chief Executive Officer Erik Palitsch

watches one of the company’s 3D printers in operation.

By Ashlee Vance

February 1, 2023

Since it first began to receive mainstream attention about 15 years ago, 3D printing has had a magical air to it, holding out the promise of turning every home into a miniature manufacturing hub while simultaneously upending the way industrial-scale factories operate. But 3D printers—which create objects by layering materials according to a plan sent by a computer—have gained a reputation for being unwieldy, expensive and slow. The utopian dream of the printers becoming a household appliance as ubiquitous as the personal computer has largely faded.

There has been more progress on industrial uses, although there, too, major players have fallen into a multiyear funk. Venture capitalists continue to dedicate significant resources to startups promising innovations to fix the technology’s underlying flaws. One particularly radical approach comes from Freeform Future Corp., a five-year-old startup based in Los Angeles. The company has raised $45 million so far from investors including Founders Fund, Threshold Ventures and Valor Equity Partners.

Instead of trying to build a single machine that can print three-dimensional objects, Freeform is looking to turn entire buildings into automated 3D-printing factories that would use dozens of lasers to create rocket engine chambers or car parts from metal powder. The company, which has never before discussed its approach publicly, says the technique could allow it to make metal parts 25 to 50 times faster than is possible with current methods and at a fraction of the cost.

Staff engineer Rueben Mendelsberg observes a 3D printer starting up at Freeform Future’s headquarters in Hawthorne, California.

Freeform’s co-founder and chief executive officer, Erik Palitsch, spent a 10-year stint at Space Exploration Technologies Corp., Elon Musk’s aerospace company. SpaceX has famously pushed the limits of 3D printing in its rocket engines, and Palitsch led a number of its highest-profile engine development programs. But he says both he and Musk knew the existing 3D printers were inadequate for the company’s most ambitious efforts. “When we told Elon how much the machines would cost for some of our new projects, he nearly lost his mind,” says Palitsch. “And it always took an army of people to operate them.”

Venture Funding to 3D-Printing Companies

Source: Crunchbase

In late 2018, Palitsch and fellow SpaceX veteran Thomas Ronacher started Freeform, hoping to rewrite some of the fundamentals of 3D printing. Typically, an object or a few objects are printed at the same time inside a shed-size machine. While it can make just about anything, the amount of work this kind of printer can do is limited by its size and its printing area.

Chief Scientific Officer Tasso Lappas oversees Freeform Future’s

3D-printing process from the control room at company headquarters.

Freeform, on the other hand, is creating machines that can fill a warehouse. Its current factory, in Hawthorne, California, used to serve as Keanu Reeves’s motorcycle storage facility. (Freeform still ends up with some of the actor’s mail.) Inside, machines shuffle objects back and forth along rapidly moving conveyors, so the system can work on many things at once. Other companies have set up multiple printers in a single facility, but this strategy doesn’t improve their speed, it just increases scale by having them work in parallel. Freeform, by contrast, is redesigning the process by which 3D printing can turn raw materials into finished products. In a sense, it’s akin to the establishment of the assembly-line process pioneered by 20th century industrialists like Henry Ford. “We have to achieve a state of mass production to open this up to more industries,” says Palitsch. “And you simply can’t get there with a conventional machine.”

Freeform’s backers are focused on the industrial realm rather than home-based production. “The main thing they will be able to do is get the price of this down to where it’s more like automotive manufacturing costs instead of aerospace costs,” says Tom Mueller, who led SpaceX’s engine development for many years and is an angel investor in Freeform. “They also just get the printing speed up by a huge amount.”

Freeform, on the other hand, is creating machines that can fill a warehouse. Its current factory, in Hawthorne, California, used to serve as Keanu Reeves’s motorcycle storage facility. (Freeform still ends up with some of the actor’s mail.) Inside, machines shuffle objects back and forth along rapidly moving conveyors, so the system can work on many things at once. Other companies have set up multiple printers in a single facility, but this strategy doesn’t improve their speed, it just increases scale by having them work in parallel. Freeform, by contrast, is redesigning the process by which 3D printing can turn raw materials into finished products. In a sense, it’s akin to the establishment of the assembly-line process pioneered by 20th century industrialists like Henry Ford. “We have to achieve a state of mass production to open this up to more industries,” says Palitsch. “And you simply can’t get there with a conventional machine.”

Freeform’s backers are focused on the industrial realm rather than home-based production. “The main thing they will be able to do is get the price of this down to where it’s more like automotive manufacturing costs instead of aerospace costs,” says Tom Mueller, who led SpaceX’s engine development for many years and is an angel investor in Freeform. “They also just get the printing speed up by a huge amount.”

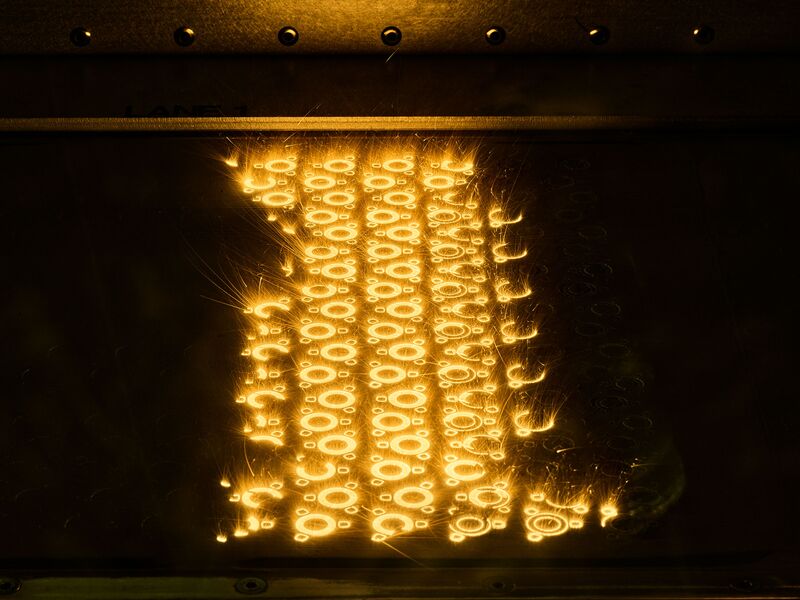

A layer of metal powder being fused.

3D printers create objects from a range of materials, including plastics and metal. Freeform specializes in the latter, using a well-known approach where a laser fires onto a bed of metal powder to fuse it into specific shapes. A new layer of powder is then applied, and the laser fires again, and again.

A typical 3D printer today might have two to four lasers and concentrate them on a single metal plate where it builds objects. The lasers hit the metal powder, then cease firing while a new layer of metal powder is placed on the plate before firing again. A limiting factor is the rate at which metal and plastic melt and fuse. Typically, the printer has to take breaks because it also gets too hot. Companies consider it a success if a 3D printer is operating 60% of the time.

Lead electrical engineer Dennis Ren manages cables connected to the lasers on top of a 3D printer.

Freeform looks to significantly reduce downtime. It has two parallel conveyor systems lined up with multiple metal plates traveling along them. Its 18 lasers fire nonstop while conveyors move plates in and out of the beams. Tasks like applying fresh metal powder to a plate or polishing the edges of a part take place in other areas of the machine, leaving the lasers to continue doing their work on other objects. A combination of cameras snap images at more than 70,000 frames per second, feeding the data into computer vision algorithms that orchestrate how the lasers fire. Where a standard machine can fuse about 100 grams (3.5 ounces) of metal powder an hour, Palitsch says Freeform does five kilograms an hour now and will do even more soon with new versions of its technology.

Palitsch

While the extra speed and lower price are bonuses, the real value of Freeform’s system is how it monitors objects during the printing process, according to Nick Doucette, chief operations officer at rocket engine maker Ursa Major Technologies, which has tested Freeform’s technology. 3D-printed parts can have flaws, and customers tend to use antiquated, manual practices to check how strong and solid the final objects are. Freeform uses its host of sensors, scanners and artificial intelligence software to assess quality and can make adjustments while something is being built. “The usual way we do this is a nightmare of testing samples and tweaking things,” says Doucette. “Freeform just prints something and gives it to me.”

A flow distributor printed by Freeform Future.

As has so often been the case in the industry, Freeform’s current machine has seemingly revolutionary potential but also a short track record and just a few paying customers. It still has a mad scientist prototype quality to it, with all manner of tubes and electronics hanging off its body. Nor is it as big or as automated as the company envisions for more developed products. For the technology to be a real breakthrough, Freeform will have to prove that its machines operate quickly and cheaply enough to open 3D printing to a wide range of new markets and to tackle traditional mass manufacturing head on.

The end goal, says Palitsch, is to have more lasers and more conveyors, adding up to a system of printers that can fill a 100,000-square-foot building. Jobs that typically take weeks will be done in hours, and few, if any, humans will be involved. “It’ll be a fully autonomous printing factory,” Palitsch says.

Photographer: Spencer Lowell for Bloomberg Businessweek

No comments:

Post a Comment