The Conversation

November 27, 2024

This finger bone discovered in Siberia in 2008 led to the original Denisovan discovery. Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

It started with a finger bone found in a cave in the Altai mountains in Siberia in the late 2000s. Thanks to advances in DNA analysis, this was all that was required for scientists to be able to identify an entirely new group of hominins, meaning upright primates on the same evolutionary branch as humans.

Now known as the Denisovans (De-NEE-so-vans), after the Denisova cave in which the finger bone was found, the past few years have seen numerous other discoveries about these people. I’ve recently co-published a paper collating everything we know so far.

So who were the Denisovans, where did they live, and why are they important to the story of humanity?

Around 600,000 years ago, early humans in Africa diverged into groups. Some migrated out of Africa, becoming Neanderthals in eastern and western Eurasia and Denisovans in eastern Eurasia.

Modern humans later evolved in Africa, spread across the globe, and encountered Neanderthals, Denisovans and possibly other unknown archaic human groups. Yet by 40,000 years ago, only modern humans remained on the archaeological record.

The genetic legacy

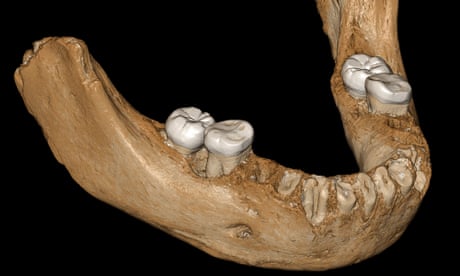

Unlike Neanderthals, whose fossils are relatively abundant, Denisovan remains continue to be very scarce. Apart from that Siberian finger bone, the main other discovery was a jawbone found in China, in a limestone cave located on the northeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. It had been believed that the Denisovans had been confined to Siberia, but this jawbone demonstrated that they had lived much further afield.

Their DNA has enabled scientists to build on this insight, since it survives in contemporary populations, particularly in Oceania, parts of Asia, and even Indigenous American populations. This shows that the Denisovans were widely distributed across these areas.

From Tibet to the Americas, the Denisovans certainly got around. Dmitry Kalinovsky

Strikingly, recent studies reveal that Denisovans interbred with modern humans multiple times. For instance, east Asians harbour ancestry from at least two distinct Denisovan populations. Also, the people of Papua New Guinea, which retain up to 5% Denisovan ancestry, a much higher proportion than other groups, interbred with at least two Denisovan groups at different times.

Additionally, research has shown that some populations from the Philippines carry a distinct Denisovan ancestry compared to their neighbouring groups. These various genetic differences highlight that the interbreeding between modern humans and Denisovans has a complex history.

Adaptations

While much about the Denisovans’ lifestyle, appearance and culture remains unknown, the discovery of the Tibetan jawbone showed that these people lived in diverse environments, and that they must have been very adaptable. Sure enough, we now know that Denisovan ancestry in modern humans has contributed to adaptive traits, particularly in challenging environments.

A notable example is the EPAS1 gene. Inherited from Denisovans, it helps regulate the body’s response to low oxygen levels, giving Tibetans a physiological advantage in the high altitudes of the Tibetan plateau.

Other human adaptations possibly derived from Denisovan interbreeding relate to being able to tolerate cold weather, and being able to metabolise lipids, which include fats and oils. These may have been beneficial for populations in northern regions, such as the Arctic. For example, Inuit populations carry Denisovan genes that help to regulate body fat and maintain warmth.

The Inuit may have the Denisovans to thank for their ability to tolerate harsh climes. Chris Christopherson

Some genes that aid in fighting infections also appear to have Denisovan origins. These immune-related genes might have played crucial roles in protecting ancient and modern humans from south and east Asia, the Americas and Papua New Guinea against specific pathogens, illustrating how Denisovan heritage continues to affect human health today.

Unanswered questions

Many questions about the Denisovans remain unanswered. For instance, how genetically distinct were these populations, and how many distinct groups existed? We know that at least four distinct Denisovan populations interbred with modern humans. However, with further analyses, this number might increase, revealing an even more complex story.

We’re also looking for a better understanding of the biological impact of Denisovan DNA in modern humans. While many beneficial traits have been identified as derived from Neanderthals, only a few have been found for Denisovans so far. Many other potential contributions remain to be explored.

This will be possible only if additional Denisovan remains are discovered and DNA is extracted and sequenced. We need more data, especially from diverse geographical regions and time periods, to provide new insights into these people’s adaptations, interactions with other hominins, and lasting legacy in human evolution.

To address these questions, our research capabilities will need to improve. For example, we need new tools to more accurately distinguish Denisovan genetic material from Neanderthal and modern human DNA.

Additionally, studying Denisovan ancestry in populations beyond east Asia and Oceania, such as Indigenous Americans, could shed light on exactly which Denisovan sources have contributed to modern humans genomes.

The discoveries to date highlight the power of genetic studies in uncovering hidden chapters of our past. Each discovery brings us closer to understanding who the Denisovans were and how their lives and adaptations continue to affect humans today.

Linda Ongaro, Research Fellow in Genetics, Trinity College Dublin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.