Observing his readers’ unexpected exuberance over The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings in the United States in the late 1960s, a somewhat dismayed J. R. R. Tolkien referred to his fans there as “my deplorable cultus,” going on to say that these people “don’t know what they’ve been moved by and they are quite drunk on it. Many young Americans are involved in the stories in a way I am not.”He was likely thinking of the long-haired hippie types, those scrawling “Frodo Lives!” as graffiti or wearing “Gandalf for President” lapel pins, but Tolkien probably had no idea just how wild his fans would get in the decades to come. In 2024, a number of prominent right-wingers embrace Tolkien’s work as the inspiration for their own ultraconservative worldview. While some Marxists may look upon this scene with bemusement, fantasy as a mode and a genre is far too important to allow the right-wingers to take for themselves, and that includes the works of Tolkien.

Among these hobbit-loving political and business leaders are veritable “Masters of the Universe,” including current Republican vice-presidential nominee, J. D. Vance, his mentor, billionaire Peter Thiel, and even the Prime Minister of Italy, Giorgia Meloni, who in her younger days attended “Hobbit Camps” run by neofascist Tolkien admirers and who continues to cite Tolkien’s work as the inspiration for her far-right political views. These celebrity enthusiasts are joined by a vast and possibly growing international cohort of Tolkien fanatics who openly embrace white supremacist, racist, anti-immigrant, neo-Nazi, and otherwise right-wing ideologies, many of whom take The Lord of the Rings as something like holy scripture.

Such fans are the bane of Tolkien Studies, and there have been incidents of trolling of lectures and conferences. This baleful discourse has also plagued Tolkien and fantasy fandom in the broader popular culture, as right-wing zealots have attacked film and television adaptations for their apparently “woke” casting and lack of faithfulness to the original or to what they imagine to be “reality” itself. Even those Tolkien fans or scholars who consider themselves relatively conservative in their political views have been alarmed by the ultra-right’s attempts to claim Tolkien as their own.

Fantasy is fundamentally the literature of alterity, a means of empowering the imagination to think of the world differently. As such it remains a vital resource for the Marxist critique of all that exists, to borrow a phrase from Karl Marx, who so effectively explored the unreality of the so-called “reality” that obscures the true social relations in societies organized under the capitalist mode of production. And by positing the nonexistent as real, as the great socialist writer China Miéville has put it, fantasy “is good to think with.”I maintain that the writings of Tolkien, who for better or worse still stands as the supremely canonical and foundational figure in fantasy, are also good to think with.

Along those lines, Marxist approaches to Tolkien are all the more necessary today, both to illuminate the potentially radical value of his work and to stand athwart the neofascists who wish to arrogate Tolkien to themselves. Marxists must “read differently,” bringing to bear the full force of a dialectical criticism that refuses facile moralism, instead analyzing the dynamic world system Tolkien’s legendarium figures forth, exposing its ideological limits while also limning its potential for helping us to imagine radical alternatives.

Reading Tolkien dialectically

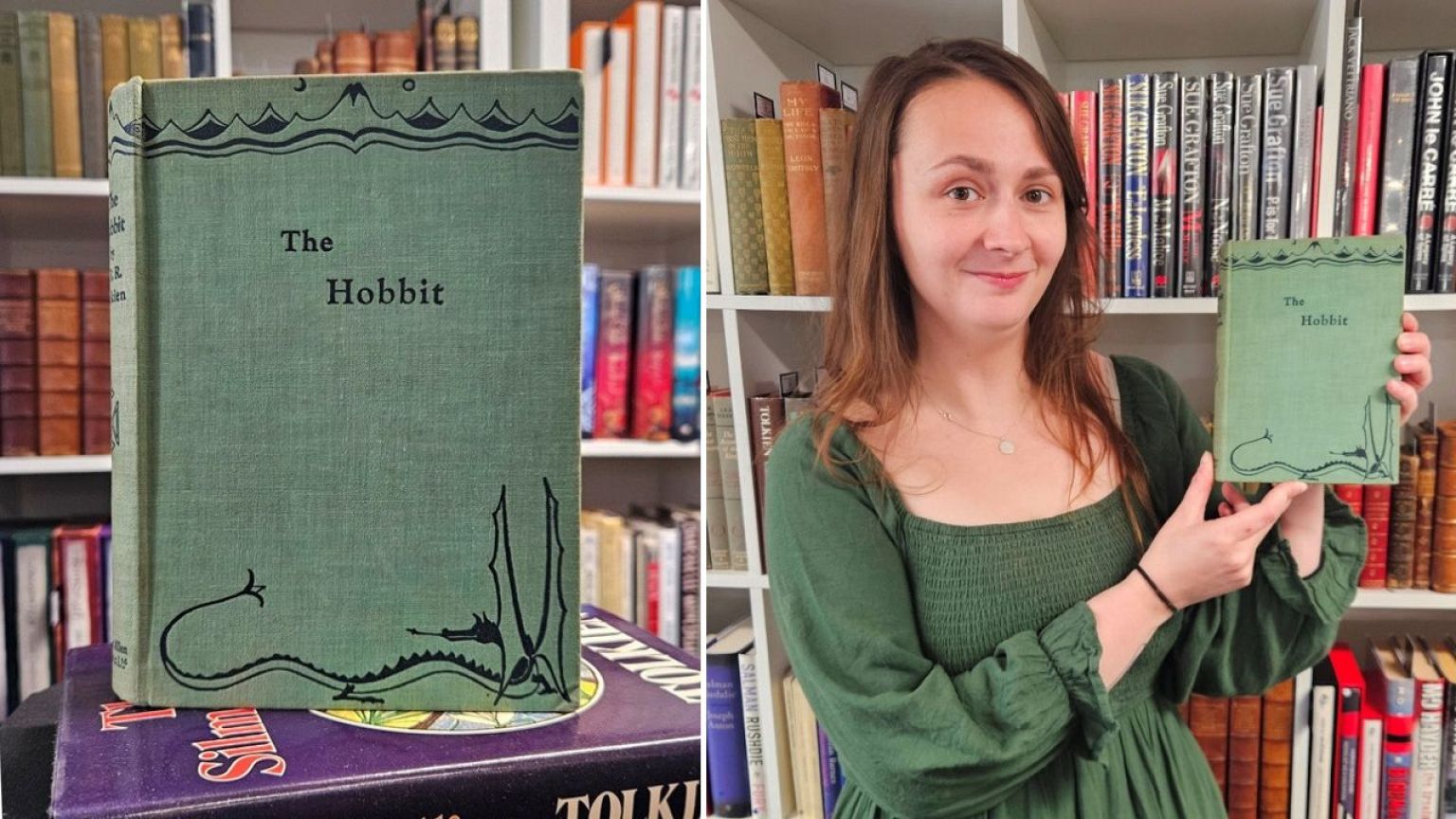

The idea that Tolkien himself would approve of tech-industry millionaires who aspire to positions of power in government is absurd on its face, but then there must be aspects of Tolkien’s writings and views that do appeal to such people. For many on the political left, the embrace of Tolkien by far-right conservatives like Vance, Thiel, or Meloni is proof positive that Tolkien’s work is inherently right-wing. Many Marxist critics have long dismissed the fantasy genre — as opposed to science fiction, for instance, not to mention realism — as reactionary, and Tolkien’s writings are viewed as emblematic of the genre’s retrogressive and illiberal sensibilities.Fantasy in its very form has been considered politically reactionary, backwards-looking, religiously oriented, and hostile to technology, all things that Tolkien’s world would seem to reinforce. Tolkien’s outsized influence on what would become a huge fantasy industry does not help the cause, as the success of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings has only spurred the popular appeal of medievalist or romantic visions of an enchanted past.

Science fiction, by contrast, tends to be seen as a more progressive genre, characterized by what critic Darko Suvin called “cognitive estrangement,” whereby everyday reality is defamiliarized (in a good, Brechtian sense) through rational if not scientific tropes, often oriented toward technology and the future. Fantasy, in this view, offers only a mythic or religious estrangement that is inherently conservative. Even so dialectically nuanced a reader as Fredric Jameson has insisted that the two genres not be conflated.Some left-leaning writers have resisted this tendency, most notably Miéville, who has criticized the Suvinian position as ideological in its own right and defended the uses of fantasy for radical political thought.And, of course, there are many other left-leaning fantasy writers out there, including Angela Carter, Michael Moorcock, Ursula Le Guin, Samuel R. Delany, Octavia Butler, Terry Pratchett, and Nnedi Okorafor, to name a few.

I, myself, have tried to push against this tendency in Marxist criticism, offering a sort of Marxist reading of Tolkien that seeks to uncover the utopian as well as the ideological import of these writings, in my books J.R.R. Tolkien’s ‘The Hobbit’: Realizing History Through Fantasy (2022), Representing Middle-earth: Tolkien, Form, and Ideology (2024), and my forthcoming book on Tolkien’s Orcs. My approach in these studies is somewhat in the vein of Jameson’s The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act (1981). Jameson himself had written an excellent study of an actual fascist writer, Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as Fascist (1979), a dialectical reading that disclosed the potentially liberatory politics latent within the archconservative’s prose. I believe that Tolkien may likewise be read in such a way that Marxists and others on the left can embrace The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and other writings as works worthy of analysis and of admiration, even if this may also involve reading them “against the grain,” to invoke Walter Benjamin’s metaphor.

A Marxist approach to Tolkien does not simply involve selective reading, looking for utopian needles in the vast ideological haystacks, but rather it would examine the totality of the work, disclosing the “positive” alongside the “negative” to be found there. Just as Marx himself discovered in the royalist Honoré de Balzac’s fiction the most fully fleshed out vision of bourgeois social relations available, just as Georg Lukács found in conservative Walter Scott’s historical romances the basis for a Marxian historicist worldview, and just as Jameson revealed the utopian potential in the fascist Wyndham Lewis’s vicious anticommunism, a dialectical reading of Tolkien’s work can elicit productive material for radical cultural criticism. Given the overwhelming popularity of Tolkien and Tolkien-related franchises today, in fact, Marxist criticism has a duty not to cede this entire domain to the right-wingers who wish to claim it as their own.

“The rising tide of orquerie”: Race and class in Tolkien

It should go without saying that a Marxist interpretation would not try to whitewash Tolkien’s own troubling views or the vexing problems to be found in his work, for example, the many involving race and class. Liberal fans of Tolkien, distraught by the enthusiastic response of white supremacists and other far-right hobbit fanciers, have rushed to defend the Professor. As if to confirm his anti-fascism, such readers often cite Tolkien’s description of Hitler as “that ruddy little ignoramus.”When in 1938 he was asked by a German publisher to confirm that he was 100 percent “arisch” (that is, Aryan, with no “Jewish blood”), Tolkien’s anger was palpable: “I am not clear as to what you intend by arisch. I am not of Aryan extraction: that is Indo-iranian…. But if I am to understand that you are enquiring whether I am of Jewish origin, I can only reply that I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted people.”This letter is frequently quoted as “proof” that Tolkien was neither profascist nor anti-Semitic, although as Robert Stuart has observed in his Tolkien, Race, and Racism in Middle-earth (2022), “philo-Semitism is just as racist as anti-Semitism, in that it ranks races hierarchically.”And there can be no question that within Tolkien’s legendarium, the various “races” (that is, Elves, Men, Dwarves, and so on, as well as their intramural subdivisions or ethnicities), are clearly ranked in a hierarchical order.

Indeed, despite the liberal apologists’ best intentions, there is obviously much in Tolkien’s work that would support the claims by white supremacists that he is one of them. The consistently racist depictions of Orcs, for example, who are invariably “swart,” “sallow-skinned,” and “slant-eyed,” is rather striking, as is the fact that, while appearing to be human in almost all respects, the Orcs are demonized and dehumanized, constantly compared to beasts, insects, maggots, and the like, not just by individual characters but by the narrator as well. Worse, even though Tolkien’s Orcs are utterly human, perhaps all too human, with personalities, families, communities, cities, and so on, the “heroes” in Tolkien’s writings hunt and kill them even in “peacetime,” without any compunction and at times quite gleefully. There is only one reference to an Orc being taken captive in all of Tolkien’s writings, and that for questioning, after which he is summarily beheaded. Even as Frodo, Gandalf, Aragorn, and others exhibit sympathy for the treacherous Gollum, the traitorous wizard Saruman, and the wicked lackey Wormtongue, no one shows the least bit of mercy or kindness for Orcs, even Orcs who are fleeing and thus pose no immediate threat. Undoubtedly, this uncompromising mercilessness toward the ostensible “enemy” may be characteristic of many on the “New Right” as well.

In a famous letter, Tolkien explicitly describes the Orcs’ appearance: “The Orcs are definitely stated to be corruptions of the ‘human’ form seen in Elves and Men. They are (or were) squat, broad, flat-nosed, sallow-skinned, with wide mouths and slant eyes: in fact degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-type.”It is easy enough to imagine Orcs as being “Oriental” in some sense, hence a threat to “the West.” In fact, by a perverse ruse of history, some Russian ultra-nationalists have in recent years embraced the idea of themselves as Russian Orcs, championing brutal force to counter the Western influence. Those who wish to claim that Tolkien was not himself racist, or that his works do not exhibit racism, are not very convincing under these circumstances. Moreover, the exoticizing and Orientalizing of the enemy obviously provides fodder to the anti-immigrant and white supremacist arguments of many on the far right in Europe and the Americas.

Notwithstanding the racist characterization of Orcs in his writings, Tolkien often imagines orkishness in the real world as defined by attitudes and values more than by racial or national character. Using the term metaphorically in a wartime letter, for example, Tolkien wrote that “There are no genuine Uruks [Orcs], that is folk made bad by the intention of their maker,” adding that “there are human creatures that seem irredeemable short of a special miracle, and that there are probably abnormally many of such creatures in Deutschland and Nippon — but certainly these unhappy countries have no monopoly: I have met them, or thought so, in England’s green and pleasant land,” elsewhere noting that “we started out with a great many Orcs on our side.”In fact, orkishness for Tolkien is often associated with technology, automation, and industry. In The Hobbit, he suggests that orcs likely “invented some of the machines that have since troubled the world, especially the ingenious devices for killing large numbers of people at once.” (As it happens, Gandalf had just killed “several” orcs at once, leaving “a smell like gunpowder,” and just a few pages later Gandalf kills the Great Goblin and many dozens of orcs along with him.)There is terrible irony in the fact that the founders and principle investors of Palantir Technologies and Anduril Industries, with their vast network of connections to various military organizations, should be devotees of Tolkien, who himself would have undoubtedly considered them the enemy.

Tolkien at times used the term “Orc” to refer to those who operated noisy machinery, announcing “there is an Orc!” when a motorcycle roared past, for instance. “Still you never quite know what is going on under the head of an apparent orc on a motor bike,” Tolkien once wrote. Tolkien also wrote of receiving a fan letter from a worker in a Siemens factory, which he described as from an “Orc,” for apparently merely working for such a company was enough to make someone an Orc. The Siemens factory in question produced massive cables for the telecommunications industry, so perhaps that too has something to do with it — the corporation for which this English “Orc” worked was literally an agent of capitalist globalization! If anything, the industries of Silicon Valley and their ilk, devoted as most are to high tech, artificial intelligence, software, telecom, and transnational commerce, would almost certainly represent the most “evil” forces in the Middle-earth of our own day, in Tolkien’s view. Far from representing wise wizards like Gandalf or doughty hobbits like Sam, these right-wing Middle-earth fanatics like Thiel and Vance would have been part of what Tolkien once called “the rising tide of orquerie.”

Right-wing hobbit fanciers

As elaborated in a recent Politico article, “‘Hillbilly Hobbit’: How Lord of the Rings Shaped JD Vance’s Worldview,” the junior senator from Ohio and current vice-presidential nominee has long cited Tolkien’s work as an inspiration for his political awakening. Naming Tolkien as his favorite author, Vance in 2021 explained, “I’m a big Lord of the Rings guy, and I think, not realizing it at the time, but a lot of my conservative worldview was influenced by Tolkien growing up.”While extolling the virtues of simple, rustic, “traditional” lives, with the hobbits of the Shire as stand-ins for out-of-work Appalachian miners or Midwestern family farmers, Vance also seems to imagine himself as a Gandalf, a gifted, well-educated tech “wizard” who can inspire the small folk to greatness while also paternalistically looking out for them.

Vance is among the latest figures in a multinational panoply of right-wing political leaders and businessmen who claim Tolkien’s ideas as the source of their own. Vance’s mentor, Thiel, has frequently mentioned Tolkien’s influence as well as (more bizarrely) that of his former Stanford professor René Girard. Thiel has founded a number of investment funds and other companies named after terms found in Tolkien’s legendarium, including Palantir Technologies, Mithril Capital, Valar Ventures, Lembas LLC, Rivendell One LLC, and Arda Capital. Thiel, along with Vance, were also key investors involved in the founding of Anduril Industries, a defense contractor. (For those not familiar with Tolkienian terminology, the palantír is a “seeing stone,” much like a crystal ball that operates at times as a form of telecommunication; mithril refers to a pure form of silver, the most valuable of all precious metals in Middle-earth; the Valar are the god-like beings, the “Powers” of the world, modeled somewhat on the Norse pantheon; lembas is the elven “way-bread,” a substance that is almost magically sustaining and healthful; Rivendell is the common name of Elrond’s elven enclave, a site of great learning and restoration in Tolkien’s universe; Arda is the name for the planet Earth itself, the world as we know it; and Andúril is the elvish name Aragorn gives to his sword, a name translated as “Flame of the West.”) Needless to say, perhaps, but these names are not merely homages to a favorite novelist’s fiction, but are calculated to symbolize the corporate mission of each entity. Palantir Technologies is deeply involved in the business of surveillance and data collection, for example, so the lost “seeing stones” of Númenor are particularly suggestive in that context.

Apparently recruited by Thiel while still at Yale Law School, Vance worked for Mithril Capital before founding — with a large investment from Thiel himself — Narya Capital, an investment fund named for the elven ring of power worn by Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings. Narya is the Ring of Fire, whose magical properties include the ability to inspire others, which suggests that in the story itself, Gandalf’s own prodigious powers as a wizard were enhanced and focused through his use of this ring. Presumably, Vance imagines his own Ivy League-formed powers to be strengthened by the sorcery of finance capital, which as Marx himself observed can involve the most phantasmagoric elements of necromancy, turning dead labor into living capital, and through leverage, generating massive effects from relatively small investments.

Vance and Thiel are more famous than most, but in recent years there has been a large and burgeoning movement of the “new right,” alt-right, white supremacist, and neofascist ideologues embracing Tolkien, drawing upon his stories and their popularity to justify their views of racial purity and European-American dominance. Members of such movements have plagued Tolkien studies and fandom, along with medieval studies and other areas, often emerging in more mainstream media in connection with popular culture and the “culture wars” attendant thereto. For example, the “diverse” casting of the Amazon Prime series The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, which features actors of color playing elves, dwarves, and protohobbits, called forth a firestorm of protest from fans, some of whom openly identified with fascist or neo-Nazi perspectives, who castigated the producers for their “woke” program. Beyond criticizing the sort of choices that go into any film or television adaptations, however, some of these Tolkien fans were questioning not merely the faithfulness to Tolkien’s own writings but also the degree to which nonwhites have any claim to Tolkien’s world at all.

Indeed, to the chagrin of many liberal, left-leaning, or even apolitical fans, the association of Tolkien with fascism has become something of a fait accompli, at least in certain circles, given the ardor of the right-wing enthusiasts. Most prominent, perhaps, is Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who honed her ideological perspective in “Hobbit Camps” run by neofascists who were also attempting to restore Mussolini-like regimes in Italy and elsewhere. As The Washington Post reported last year, “for Meloni and a horde of fantasy-loving politicians in Italy’s far right, nothing is more precious than the works of Tolkien, in whose writing they see themselves as a ragtag fellowship battling the Lidless Eye of the European left. Italy’s post-fascist far-right hosted ‘Hobbit Camps’ for young conservatives as far back as the 1970s.”A Guardian article noted that, in her own book, Meloni claims that her favorite character “is the peace-loving everyman Samwise Gamgee, ‘just a hobbit.’” A few pages later she’s implicitly likening Italy to the lost kingdom of Númenor and citing the character Faramir’s call to arms in The Two Towers. Ultimately, she seems to view Tolkien’s work as a didactic antiglobalization fable, a hyperconservative epic that advocates a full-blown war against the modern world in the name of traditional values.”In November 2023, Meloni’s government launched a massive exhibit at Rome’s National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art on Tolkien’s work and memorabilia.

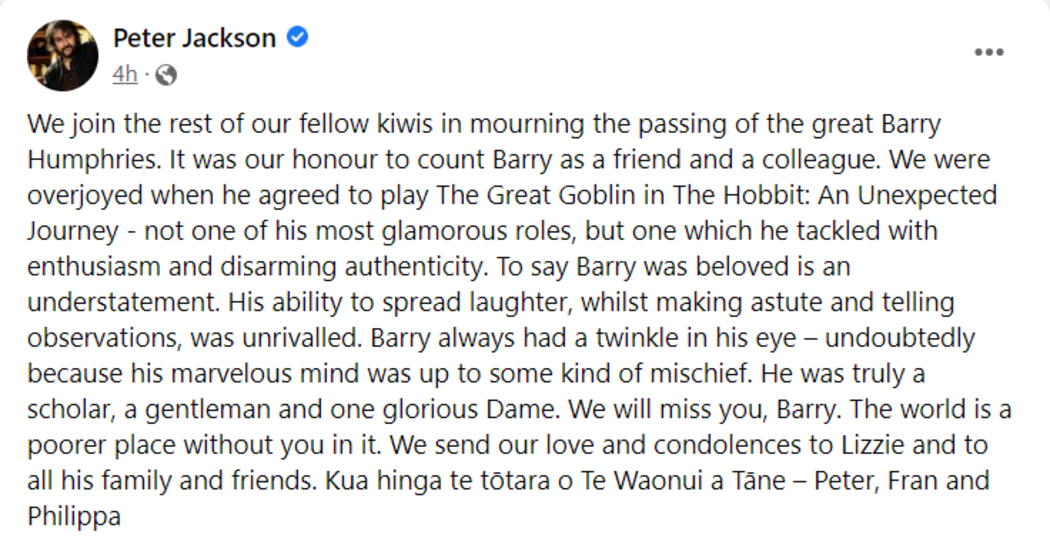

Meloni, for her part, was obviously deeply involved in Italian neofascist Tolkien communities early on, attending Hobbit Camp — she has referred to it as a “political laboratory” — already in the early 1990s. But it seems that the rapid spread of Tolkien’s influence among right-wing groups and individuals came only after December 2001, with the release of the Peter Jackson-directed adaptation The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, followed by the next two installments (The Two Towers and The Return of the King) hitting theaters in 2002 and 2003. The timing was serendipitous, as this was arguably the first international blockbuster film and franchise to emerge after the attacks of September 11, 2001, with The Two Towers released on the eve of the US invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan by the “coalition of the willing” who were to be combatting what President George W. Bush had dubbed “the Axis of Evil.”

Suddenly, an epic adventure in which wise leaders working with simple “small folk” in the attempt to overcome a vast and evil empire bent on covering the world in darkness took on additional resonance for many viewers. For some, undoubtedly, the “clash of civilizations” heralded by Samuel P. Huntington could be easily transcoded onto Middle-earth, with the Easterlings, Southrons, the peoples of Mordor, and above all Orcs (that is, servants of an “evil” Sauron) being opposed to the very existence of the “free peoples of the West,” who quickly became coded as white, Christian, capitalist, and “freedom-loving.” This timing made a right-wing interpretation of Tolkien’s works all the more salient.

It did not help that the films are far less nuanced than the novel upon which they are based, presenting a much more simplistic good-versus-evil scenario than that to be found in Tolkien’s own writings. Far be it for me to suggest that the right-leaning Tolkien super-fans like Vance do not read, but I think it is noteworthy that their sense of what “Tolkien” thinks seems to stem more from Jackson’s film adaptations (2001–2003) than from the novel itself, first published in three volumes in 1954 and 1955 (then released in its authorized paperback edition in the U.S. in 1965). Even Thiel, who has cited Tolkien as a formative influence in his life, managed to found or cofound numerous companies and funds — including Fieldlink (later renamed Confinity), PayPal, and Clarium Capital Management — that did not have Tolkien-inspired names in the years before the Jackson movies appeared; Palantir Technologies was founded only in 2003, by contrast. In Vance’s case, he would have only been seventeen years old when the first film was released, but then many of us read Tolkien in or even before high school. Still, he likely “came of age” amid the coincidental maelstrom of post-9/11 geopolitics and Lord of the Rings’s pop-cultural dominance.

“Dynamiting factories and power-stations”

As for Tolkien’s own personal political beliefs, which likely changed slightly over the years, Tolkien certainly opposed communism, socialism, or other left-wing programs, yet some anarchists have claimed him.Most likely, Tolkien favored a political order somewhat like that of the Shire at the beginning of the Fourth Age (that is, after the conclusion of The Lord of the Rings), in which a relatively autonomous, culturally homogenous, somewhat isolated, and mostly self-governing community existed as part of a larger kingdom, where a distant and largely disinterested, though powerful, monarch saw to it that a status quo was maintained. In a letter dated November 29, 1943, Tolkien wrote,

My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning abolition of control not whiskered men with bombs)—or to “unconstitutional” Monarchy. I would arrest anybody who uses the word State (in any sense other than the inanimate realm of England and its inhabitants, a thing that has neither power, rights nor mind); and after a chance of recantation, execute them if they remained obstinate!…Give me a king whose chief interest in life is stamps, railways, or race-horses; and who has the power to sack his Vizier (or whatever you care to call him) if he does not like the cut of his trousers.

Lamenting the “frightful landslide into Theyocracy,” Tolkien adds that “the special horror of the present world is that the whole damned thing is in one bag. There is nowhere to fly to.” The interconnectedness of nations and peoples is part of the problem with the modern world, in Tolkien’s view, which leads him to write these somewhat devastating lines: “There is only one bright spot and that is the growing habit of disgruntled men of dynamiting factories and power-stations; I hope that, encouraged now as ‘patriotism,’ may remain a habit! But it won’t do any good, if it is not universal.”Undoubtedly there are those among the right-wing Tolkien enthusiasts who would champion these notions of patriotic industrial sabotage or terrorism, but it seems unlikely that captains of industry and their allies (like Thiel or Vance) would do so. If nothing else, it would be very bad for their businesses and for the “working-class” people employed in those factories.

Tolkien’s own political and religious views are generally understood to be conservative, based in large part on his devout Roman Catholic values and his mistrust of modernization, reform, and “progress.” But he was not a supporter of fascism. If anything, as Stuart has suggested, Tolkien’s profound traditionalism may have made him more conservative than the fascists, who were after all quite modernist in their own ways, not to mention the fascists’ far-right appeal to a nationalist populism that would have seemed vulgar in comparison to Tolkien’s more aristocratic social sensibilities. In Tolkien’s legendarium, for instance, hereditary elites like Galadriel, Elrond, and Aragorn are the ones fit to rule, plus Dain among the Dwarves, Théoden or Bard among “Men.” And even in the relatively more democratic Shire, the “betters” among the hobbit families (the Tooks, the Brandybucks, the Bagginses) are recognized as such by their ostensible inferiors. Notably, when Sam ascends beyond his initially lowly station at the end of The Lord of the Rings, he adopts the name “Gardner” for his clan, dropping the plebian “Gamgee.”

As for being a conservative, Tolkien was not particularly loyal to the Tories, many of whom he felt were part of the problem; he opposed the imperialism of the British Empire, pointing out that “I love England (not Great Britain and certainly not the British Commonwealth (grr!)).” Remarking on a wartime photo of the Allied leaders, Tolkien says that “our little cherub,” Winston Churchill, “actually looked the biggest ruffian present,” even as Churchill was sitting next to “that bloodthirsty old murderer Josef Stalin.” Indeed, Tolkien’s real fear is of the “Americo-cosmopolitanism” to come, “when they have introduced American sanitation, morale-pep, feminism, and mass production” throughout the whole world.

Today’s conservatives like Vance might well agree about American “feminism” (whatever that meant in 1943), but it is hard to believe that the founder of Narya Capital Management would be opposed to mass production and a global marketplace. Indeed, the far-right Tolkienians seem to be blithely selective in their uses of Tolkien’s work and ideas, embracing at times a romantic anticapitalism that lauds the “common man” in a preindustrial epoch, while at others insisting on support for the heaviest of heavy industries (mining, steel, automobiles, nuclear power, etc.) as well as championing the high tech sectors — Silicon Valley is, after all, the utopian “Shire” for Thiel and his minions — and seeking ever greater influence worldwide. The rhetoric of antiglobalization remains part of the populist message, of course, but it is difficult to imagine that people running Palantir Technologies, Mithril Capital, or Anduril Industries, veritable agents as well as beneficiaries of globalization, are themselves opposed to this worldwide financial, military, and industrial system.

Beyond good and evil

Where the far-right Tolkienians are perhaps most at home in Tolkien’s work can be found in their sense of moral certitude. Tolkien’s critics have accused him of establishing a world of overly simplistic good versus evil, with little room for nuance or interpretation, and these right-wing Tolkien fans often champion that aspect as a strength in both his work and his worldview. That is, the “moral clarity” of Tolkien can overcome the ambiguities and complexities of modern, and later “postmodern,” politics and culture, thus allowing wise Gandalf- or Galadriel-like leaders, along with their earnest common-folk acolytes like Frodo and Sam, to know what is right and what is wrong, and to act accordingly.

Yet here is where the misreading of Tolkien is most pronounced. Notwithstanding the many times words like “good” and “evil” appear in his writings, Tolkien consistently recognized the ambiguities and uncertainties with respect to the ethical dimension. Most importantly, he denied that evil even exists, while noting that most of what we take to be “evil” in the world derives from noble sentiments and good intentions.

“I do not deal in Absolute Evil. I do not think there is such a thing,” Tolkien explained, adding “I do not think that at any rate any ‘rational being’ is wholly evil. Satan fell. Morgoth fell before the creation of the physical world.” Sauron, who comes as close to an “evil” being as there is in The Lord of the Rings, was not evil at heart, but rather, “He had gone the way of all tyrants: beginning well, at least on the level that while desiring to order all things according to his own wisdom he still at first considered the (economic) well-being of the other inhabitant of the Earth.” Tolkien then points out that Sauron fell victim in part to his own good intentions, which were to rehabilitate Middle-earth, to bring harmony and order to a state of desolation and chaos, and to improve the lives of the people in the world. Tolkien observes that “When he [Sauron] found how greatly his knowledge was admired by all other rational creatures and how easy it was to influence them, his pride became boundless,” and as we know from Proverbs, “pride goeth before destruction and a haughty spirit before a fall.”

Ironically, perhaps, Vance seems to model himself after this vision of Sauron, although he clearly would not think of himself as such. When Vance imagines himself as a Gandalf, a wise leader looking out for the interests and well-being of the “small folk” of various Shire-like rural communities such as those in Appalachia, he is in fact embracing Sauron’s position, at least as Tolkien understands it. Within The Lord of the Rings, part of the reason that Gandalf, as well as Galadriel and Aragorn, reject the opportunity to use the One Ring is that they realize that with such power they could not help but dominate others to the ultimate detriment of all, including themselves. It is not that the ring itself is evil — another bizarre idea introduced in Jackson’s films that is not present in the novel — but that it enhances the power of its users to make their will more speedily effective. Tolkien was canny enough to know that even a “good” person using such power, using it for the good, would “fall” into what (in retrospect, at least) would be seen as evil. There is an element here of the old saws about “the road to hell” and “power corrupts,” of course, but the main point is that Tolkien is not in fact dividing his world between forces of good and evil, but between those who desire to attain power (including the power to “do good”) and those who would abjure it. Indeed, in a 1959 letter responding to a reader’s query about what would have happened had Gandalf taken the ring, Tolkien wrote, “Gandalf as Ring-Lord would have been far worse than Sauron,” largely because he would have been “self-righteous,” thus more dangerous; “Gandalf would have made good detestable and seem evil.”This is a fair warning to any Gandalf admirers who seek economic or political power in this, our all-too-real world, a caveat that the right-wing Tolkien admirers appear unlikely to heed.

In fact, it seems that many of the far-right Tolkien enthusiasts have translated key elements of The Lord of the Rings into a would-be hegemonic political and economic program for the US and the world today. This plan simultaneously posits a profoundly elitist, ultramodern power structure alongside a populist, demotic appeal to tradition. In this way, the right-wing Tolkien fanatics can envision themselves as both Gandalf and Sam Gamgee with equal aplomb, thus embodying the most powerful “good” being in the world with the most lovable and simplest everyman character, one who is working-class to boot. In this model, they can simultaneously envision themselves as ordinary people and as powerful wizards, whose elite educational backgrounds (Yale, Stanford, and so on) signify their greater “wisdom,” and whose mastery of the technological domains (Silicon Valley, venture capital, defense industries, and so on) exemplify their well-nigh “magical” abilities to operate effectively in a complex and dangerous world. These great masters are able to rouse and inspire the common people, which is to say hobbits, in the rural backwaters (that is, the Shire) through various related movements (for example, the Tea Party, Make America Great Again, the War on Woke, and now anti-DEI), which in turn convinces these “small folk” that they are essential to “saving the world” from whatever threatens it. Sauron and the One Ring, along with Saruman’s industrialism, increased immigration of “Swarthy Men” and “squint-eyed Southerners,” and the threat of Orcs (and “half-Orcs”!), become figures for liberalism, globalization, “diversity, equity, and inclusion,” and so forth.

In opposing such enemies, these wizards and the hobbits seek the return of the king — in the US in 2024, that’s Trump, naturally, but in any case a “strong” executive leader — who will then preside over various fiefdoms that will actually be “corporate monarchies,” seemingly autonomous locales that are in fact postmodern variations of the old “company towns,” now more or less under the dominion of billionaires like Elon Musk or Peter Thiel, or else their designees and assigns (since God knows they don’t have the time, energy, or competence to run governments). There is certainly a neofeudalist aspect to this, hence the rhetoric of romantic anticapitalism even among these titans of industry and abject apologists for capitalism, but ultimately the model is that of a corporate oligarchy in which “ordinary” Americans are ruled with an iron fist formed by an invisible hand, right down to the meticulous policing of borders, workplace policies, home ownership, privacy, and so forth.Tolkien’s medievalist fantasy vision thus becomes a part of the plan for an utterly postmodern, twenty-first century reorganization of society in general.

Conclusion

When Tolkien referred to his American enthusiasts as his “deplorable cultus,” he was not objecting to the perceived liberalism or left-wing views of these American readers — in any case, we know that many who were thought of as hippies became, or turned out to be, quite right-wing themselves. Rather, he was registering their fundamental misunderstanding of his work, which had a mostly melancholy tone and thus did not merit the spirited exuberance of many of its fans. It was a “heroic romance” without a hero, or rather, with so many heroes acting in various uncoordinated ways which ultimately leads to the unexpectedly happy ending, what Tolkien called the eucatastrophe, but which also created a more prosaic world devoid of enchantment in its wake. Tolkien hints throughout The Lord of the Rings at something like Divine Providence, but as Jameson has pointed out, this is ultimately a vision of History itself, hence well suited to a Marxist critical perspective that could “rewrite certain religious concepts — most notably Christian historicism and the ‘concept’ of providence, but also the pretheological systems of primitive magic — as anticipatory foreshadowings of historical materialism.”Jameson famously asserted that “History is what hurts,” and ultimately, in Tolkien’s own view, The Lord of the Rings is a story about History, the “long defeat” (as Galadriel calls it), which is why even in apparent triumph an aura of mourning and loss is pervasive.

For Tolkien, a conservative Roman Catholic skeptical of modernization in all its vicissitudes, the image of reality in Middle-earth (that is, the world we live in) as the Vale of Tears is understandable. But for those of us who find this world objectionable in other ways, such as in the dominance of the wealthy and powerful over others, might see in the transformation of the social order preferable alternatives. Tolkien, perhaps despite himself, makes possible a vision of a world in which les damnés de la terre du milieu (“the wretched of Middle-earth”) can make for themselves a life worth living. The right-wing embrace of Tolkien is rooted in establishing and maintaining an order that resists change, but even Tolkien knew that change is inevitable. While he may have mourned that fact, Tolkien also opens up the imaginative spaces in which to celebrate its potential for building a better world, a world without “Big Bosses,” as Tolkien allows even his orcs to dream of in The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien is not himself a Marxist (far from it!), but his work is well suited to a Marxist analysis that may disclose elements of the political unconscious and counter-narratives implicit in the texts, which in turn may stand in opposition to the facile and self-serving misreadings of Tolkien’s right-wing fans. It may not be possible to rescue Tolkien from his far-right admirers, fascist hobbit campers, and palantíri-obsessed corporate Big Brothers, but there is ample space within Tolkien’s own writings for alternative interpretations. The left cannot cede the literature of alterity and of the imagination, of which fantasy in general and Tolkien in particular represent crucial forms, to those on the right who ultimately seek to foreclose the imaginative and the political possibilities available to us. The deplorables who make up Tolkien’s present-day cultus ought not be given the final say in the matter, nor should they be permitted to forge and wield their own rings of power.