Mayor Mamdani and the Roots of Islamic Democratic Socialism

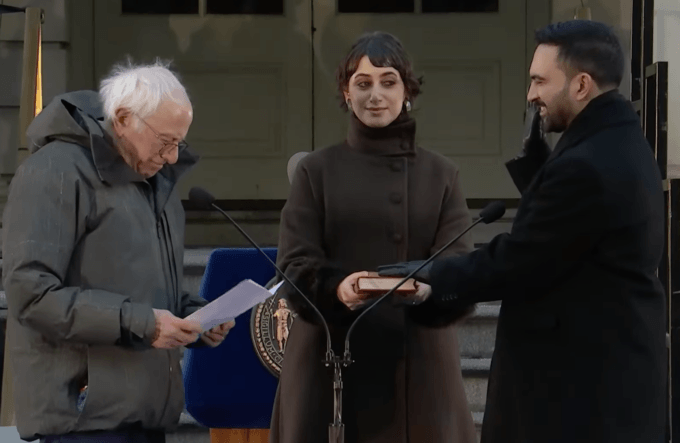

Photograph Source: NYC Mayor’s Office – CC BY 4.0

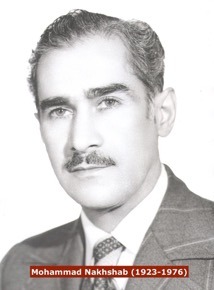

On a hot September day in 1976, Mohammad Nakhshab, an Iranian political figure, died of a heart attack on a New York subway car. He was 53. His death happened not far from the abandoned subway station under the City Hall in which Mayor Mamdani took the oath of office in the early hours of January 1, 2026. Nakhshab worked at the United Nations but was not just an ordinary employee. He was one of the founders of an influential movement in Iran in the 1940s known as the Movement of God-Worshiping Socialists. I write this to propose that one need not to view Mayor Mamdani’s Muslimhood incidental to his democratic socialist politics. Nakhshab and his companions belonged to a generation of Iranian intellectuals who believed that democratic socialism defines the social, political, and economic language of Shi‘ism in the contemporary world.

Iran was occupied by Allied forces in 1941. They ousted Reza Shah, who had Nazi inclinations, and installed his young son, Mohammad Reza, to the throne. By the end of the war, a period of civil liberties emerged. Members of the Iranian Communist Party, the first communist party in Asia, reemerged after more than a decade of persecution under Reza Shah and formed a new anti-Fascist coalition called the Tudeh Party (party of the people). Socialist ideas and movements had a presence in Iran since the 1890s. But with the triumph of the 1917 revolution in Russia, socialism became intrinsically associated with Bolshevism and communism. The Tudeh party was no exception. It became a communist party in-line with positions and demands of the Soviet Union.

Concerned about the growing identification of socialism with Soviet communism, a group of young students in the holy city of Mashad with anti-colonial aspirations who remained committed to socialist i deas laid the foundation of a movement called God-Worshipping Socialists. In choosing the name of their movement they emphasized that despite their Shi‘i convictions, they did not regard the undertaking an exclusively Muslim affair. Rather, they thought that belief in God needs to be translated in general terms into a spiritual force that propels modernity toward socialist ideals of justice and dignity.

deas laid the foundation of a movement called God-Worshipping Socialists. In choosing the name of their movement they emphasized that despite their Shi‘i convictions, they did not regard the undertaking an exclusively Muslim affair. Rather, they thought that belief in God needs to be translated in general terms into a spiritual force that propels modernity toward socialist ideals of justice and dignity.

Nakhshab and his movement understood the notion of Towhid (oneness of God, monotheism) as a spiritual directive for the promotion of oneness of all beings as the extension of God, against exploitation of all kinds of lifeforms. They stayed clear of the Sharia and the juridical debates on Islamic law. They saw their movement as an outlook, a weltanschauung, a worldview that finds its realization through collective decision-making in particular situations.

Those ideas became an engine that shaped the ideology of the 1979 revolution in Iran. Similar movements in Catholicism gave rise to the idea of Liberation Theology with lasting influences in Peru, Nicaragua, El Salvador and other Central and South American countries. Thinkers such as the Sorbonne educated theologian and social critic Ali Shariati rearticulated the basic principles of the Movement of God-Worshipping Socialists into a full-scale emancipatory ideology. Shariati warned that movements are always at risk of becoming bureaucratized and losing their spirit of creativity and novelty. He believed that once a movement realizes itself with access to the institutions of power, saving the institutions of power takes precedence over perpetuating the spirit of the movement.

We have seen this repeatedly in so many different places. I wonder how much Mayor Mamdani knows about Mohammad Nakhshab and his movement, or whether he has heard of Ali Shariati. But there is a lesson here to cherish and principles to live by. God-Worshipping Socialists believed in social justice not only in material terms but justice as a principle of full human dignity and spiritual fulfillment. Mamdani faces a herculean task, to sustain a movement while governing the city. Here, I believe, lies the core of the kind of socialism that Mamdani needs to remain committed to. A form of socialism that refuses to worship the instruments of power and sustains the spirit of a movement that has given rise to it.

Neither Nakhshab, nor Shariati lived to see the result of the revolution they helped to inspire. There are fundamental differences between what happened in Iran after the revolution and assuming the mayor’s office in New York City! But the temptation to worship the institutions of power is not something that creeps up overnight. Bureaucracy dictates its own logic, the logic of self-preservation, upon its office holders. To remain in the office cannot be the objective. Nakhshab and the socialists of his generation found the solution in a kind of spiritual commitment that was informed by their Towhidi worldview, inspired by teachings of Islam but all-embracing of all creeds that negate exploitative relations between all forms of beings. Let’s hope that our new mayor will uphold those principles of hope. Nakhshap died almost half-a-century ago not far from the office of our new mayor. Let us hope that Mamdani continues to practice the kind of Shi‘ism that Nakhshab dreamed of, a religion that promotes human dignity through socialist ideals.

No comments:

Post a Comment